Stress fractures

Ferco Berger, Milko de Jonge, Robin Smithuis and Mario Maas

From the Radiology Department of the Academical Medical Centre, Amsterdam and the Rijnland Hospital, Leiderdorp, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

One of the most common injuries in sports is the stress fracture.

In this review we will discuss:

- Clinical and imaging features of stress fractures

- Common locations of stress fractures.

Stress fractures

Location

A stress fracture is an overuse injury.

Bone is constantly attempting to remodel and repair itself, especially when extraordinary stress is applied.

When enough stress is placed on the bone, it causes an imbalance between osteoclastic and osteblastic activity and a stress fracture may appear.

Muscle fatigue can also play a role in the occurrence of stress fractures.

For every mile a runner runs, more than 110 tons of force must be absorbed by the legs.

Bones are not made to withstand so much energy on their own and the muscles act as shock absorbers.

As muscles become tired and stop absorbing, all forces are transferred to the bones.

Stress fractures usually occur after a recent change in training regimen has

taken place.

Especially professional or recreational athletes and militairy

recruits are subject to change in training intensity (increased), type of

training or training circumstances (new shoes, other training surface etc.)

and thus at increased risk of developing a stress fracture.

However,

sedentary people may also develop stress fractures if suddenly an active

lifestyle is adopted.

Insidious onset of pain and swelling over the affected region is the most important complaint, initially during the activity.

With ongoing exposure, pain will last after the training, eventually causing the athlete to stop exercising.

Finally pain is experienced at rest.

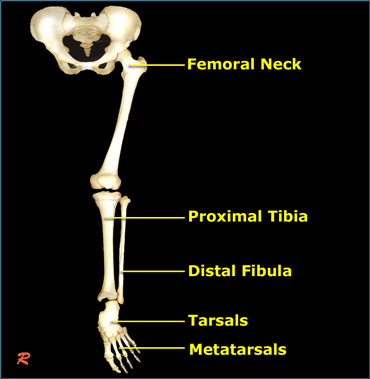

Stress fractures are most common in the weight-bearing bones of the lower extremity, especially the lower leg and the foot (Figure).

Typical stress fracture of the distal shaft of the second metatarsal not seen on initial radiograph (left). Callus formation is seen at 4 weeks follow up.

Typical stress fracture of the distal shaft of the second metatarsal not seen on initial radiograph (left). Callus formation is seen at 4 weeks follow up.

Radiography

Radiographs have a sensitivity of 15-35% for detecting stress fractures on initial examinations, increasing to 30-70% at follow up due to more overt bone reaction.

Therefore, radiologists should not be comforted by negative radiographs and should initiate further state of the art imaging.

Radiographs are however mandatory in order to show

overt fractures and to rule out other diseases,

like infections or tumours.

On the left a 42-year old female who walks long

distances and has been experiencing forefoot pain for a month.

On the initial radiograph no fracture is seen.

After 4 weeks, a follow up radiograph clearly marks callus formation at the site of the stress fracture.

Stress fracture: Normal radiograph, while STIR image already shows a high signal intensity of the bone marrow

Stress fracture: Normal radiograph, while STIR image already shows a high signal intensity of the bone marrow

On the left a 28-year old female with recent onset of pain over a region of the 2nd metatarsal bone.

At presentation, the radiograph was negative for fracture of the second metatarsal bone.

An MRI STIR (Short TI Inversion Recovery)sequence showed a high signal intensity of

bone marrow and the surrounding soft tissue,

indicating bone marrow edema as a result of a

stress fracture.

Stress fractures radiographically show the following signs:

-

osteal bone

- endosteal or periosteal callus formation without fracture line

- circumferential periosteal reaction with fracture line through one cortex

- frank fracture

-

cancellous bone

- flake-like patches of new bone formation (2-3 weeks)

- cloudlike area of mineralized bone

- focal linear area of sclerosis, perpendicular to the trabeculae

MRI

MRI has surpassed bone scintigraphy as the imaging tool for stress fractures, showing equal sensitivity (100%) but a higher specificity (85%), probably by giving better anatomical detail and more precisely depicting the tissues involved.

STIR (short tau inversion recovery), T1-weighted (T1WI) and T2-weighted images (T2WI) are used for characterization and grading.

Grading is based on signs seen at MRI:

- mild - moderate periosteal edema on STIR, no marrow changes

- moderate - severe periosteal edema on STIR + marrow changes on T2WI

- 2 + marrow changes on T1WI

- fracture line visible

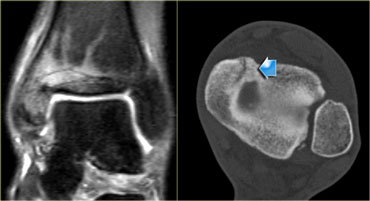

On the left a 22-year old female, a professional athlete with a recent onset of forefoot pain, persisting after training.

At presentation MRI showed a high signal on the STIR- and a

low signal on T1WI (i.e. grade 3 stress

fracture).

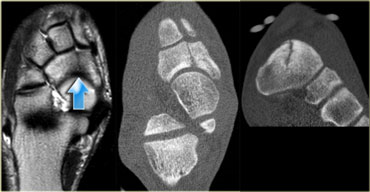

On the left a 27-year old soccer player in the

highest league of amateur football.

He suffered from midfoot pain with a recent increase in

complaints.

T1WI shows a definite fracture line in the navicular bone, indicating a grade 4 stress fracture.

Corresponding CT shows a fracture line and sclerosis on the axial images and coronal reconstructions.

Femoral neck fractures

There are two types of stress fractures of the femoral neck:

- Compression fracture. These are located on the inner side of the femoral neck.

They have a low risk of complicated healing with conservative therapy, because the fracture parts are pressed together. - Tension fracture. These are located on the outer side of the femoral neck.

They have a high risk of complicated healing due to tension exerted on the fracture elements. These fractures are at risk for complete fracture and avascular necrosis.

If conservative therapy fails, open reduction and internal fixation is recommended.

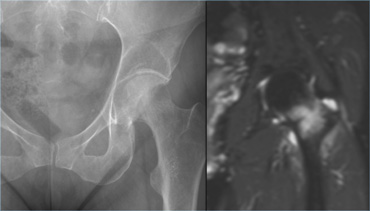

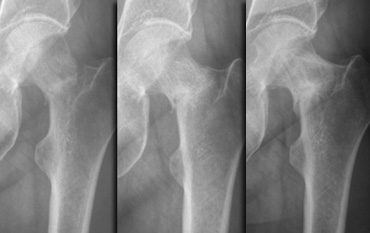

On the left we see a compression fracture of the femoral neck.

The radiograph is normal, but MR depicts the fracture and bone marrow edema (i.e.grade 4).

A radiograph made one month later shows evolvement to

complete fracture.

Although this is a low-risk fracture, the follow-up radiographs at 3 and 13 months did show poor healing tendency.

Fractures of Tibia and Fibula

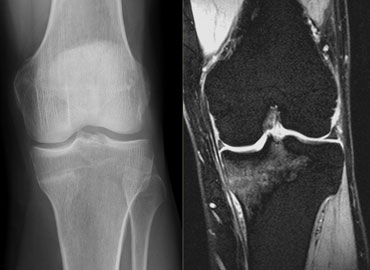

Stress fracture on the medial side of the proximal tibia in a 42-year old runner. Courtesy Dr Wuisman (3)

Stress fracture on the medial side of the proximal tibia in a 42-year old runner. Courtesy Dr Wuisman (3)

Tibia

The tibia is the most common location of stress fractures (more than 50%).

On the left a 42-year old man with pain in his left knee.

The pain had started gradually during a 10-mile running competition.

The initial x-ray was reported as normal, but a T2-weigthed gradient echo of the knee shows bone marrow edema in the proximal tibia indicating the presence of a stress fracture.

In retrospect, the sclerotic line on the x-ray also indicates the stress-fracture.

X-ray and CT-scan showing a fissure at the insertion of the flexor digitorum longus muscle. Courtesy Dr Wuisman (3)

X-ray and CT-scan showing a fissure at the insertion of the flexor digitorum longus muscle. Courtesy Dr Wuisman (3)

On the left a 24-year old runner with pain in his lower leg since four months.

Initially the pain was only present during running, but finally it was present even in rest.

The x-ray was initially reported as normal.

A bone-scan (not shown) showed a focal increase of activity.

A CT-scan was performed for further differentiation and revealed a vertically oriented fissure at the insertion of the flexor digitorum longus muscle.

The patient was treated with six weeks of rest, followed by a gradual increase in training-activity.

On the left a 50-year old male, who led a sendentary life.

He participated in a 10-mile walking contest without any training beforehand.

Gradually pain developed in the lower leg and in

the end he was unable to walk any further.

The x-rays show a stress fracture of the lower tibia.

Doing too much too soon is a common cause of stress fractures.

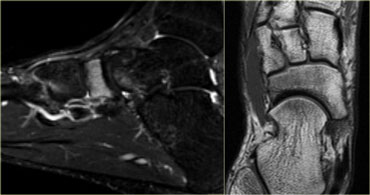

On the left a 25-year old professional soccer player with complaints of the ankle.

Evident marrow abnormalities on coronal STIR

sequence MRI was seen, but there was doubt about

the presence of a fracture line.

At 11 months follow-up a clear fracture line is visualized by CT.

On the left the postoperative radiograph with screws and lower leg cast at 12 months.

It shows a just discernable fracture line at the

typical location: the junction of the tibial plafond

and inner vertical line of the medial malleolus

Bilateral stress fracture of the distal fibula: Initial radiographs and Bone scintigraphy at 2 weeks follow up.

Bilateral stress fracture of the distal fibula: Initial radiographs and Bone scintigraphy at 2 weeks follow up.

Fibula

Fibular fractures account for 10% of stress fractures.

Stress fractures of the fibula typically occur in the distal one-third.

On the left an athlete with pain just above both

ankles, more pronounced on the left than on the right.

Radiographs made at presentation were unremarkable.

Bone scintigraphy 2 weeks later shows stress fractures of the distal fibula on both sides.

The radiograph at 6 weeks follow-up (not shown) confirmed bilateral stress fractures with healing tendencies.

Fractures of the Foot

Tarsal bones

The navicular bone is the most common site for stress fractures of the tarsus.

On the left a 16-year old male athlete with a high weekly mileage.

He complained of a recent onset of midfoot pain during training,

lasting for several hours afterwards.

There is high signal intensity in the navicular bone on the sagittal STIR-image.

On the axial T1WI there is low signal intensity, but no definite fracture line.

Metatarsal bones

The metatarsal bones are common sites for stress fracures (25% of stress fractures).

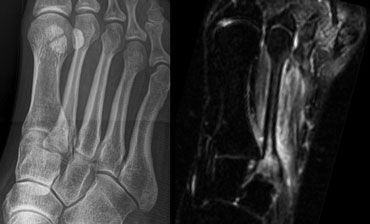

On the left a 15-year old female with no history of trauma.

Recent onset of lateral forefoot pain with walking.

The radiograph taken at presentation is unremarkable.

Follow-up at 3 weeks shows complete fracture of the distal shaft of the 4th metatarsal with overt periosteal reaction

On the left a 39-year old female with forefoot pain which began during a biking holiday.

The radiograph at presentation is normal.

At 1 and 3 months follow-up, clear healing tendencies can be seen, indicating the presence of a stress fracture

Sesamoid bones

Sesamoid bones are uncommon sites for stress fractures.

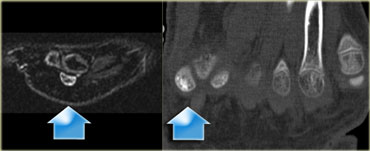

On the left a 14-year old male soccer player with persistent plantar forefoot pain.

Stress fracture of the medial sesamoid of the

great toe is indicated by a high signal intensity

on an MR sagittal STIR-sequence at

presentation.

A CT performed at presentation shows sclerosis of the medial sesamoid and confirms the diagnosis of stress fracture.

High and low risk stress fractures

Stress fractures can be divided into high and low risk stress fractures according to their likelihood of uncomplicated healing with conservative therapy.

High Risk fracture sites:

- Femoral neck tension fracture

- Transverse patellar fracture

- Midshaft anterior tibial facture

- Medial malleolus

- Talus

- Tarsal navicular

- 5th metatarsal

- Sesamoid great toe

Low Risk fracture sites:

- Femoral neck compression fracture

- Longitudinal patellar fracture

- Fracture of the posteromedial aspect of the tibia

- Fibula

- Calcaneus

- 2nd + 3rd metatarsal