Large airway disease

Onno Mets and Hans Daniels

Radiology and Pulmonology department University Medical Center Amsterdam

Publicationdate

Pathology of the

trachea and central bronchi is infrequently encountered, and therefore most

radiologists find it challenging.

Although there is a relatively limited differential diagnosis, pathology

nevertheless varies between congenital, benign, primary malignant and

metastatic disease.

This article summarizes the typical imaging features of the differential diagnostic considerations of large airway diseases and hopefully serves as a reference for those that need it every now and then.

Introduction

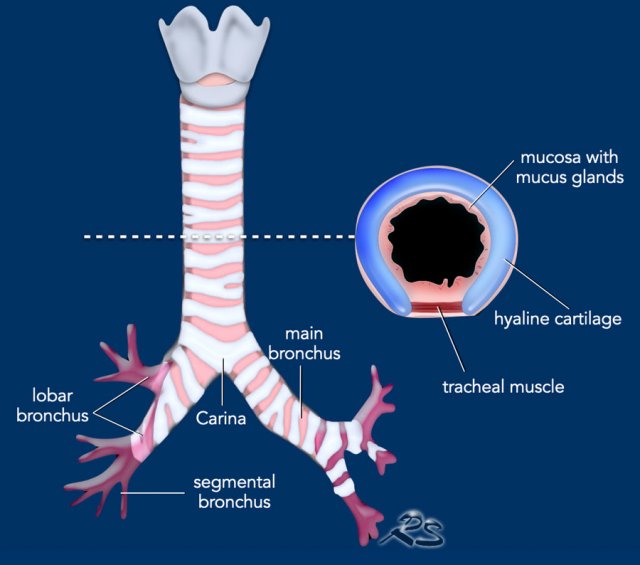

The central airways consist of the

trachea and main bronchi, before the airways branch towards the periphery into

the lobar, segmental and subsegmental airways on both sides.

The trachea has a length of about 10-15 cm and has an extrathoracic and

intrathoracic component. It contains about 15-20 horseshoe shaped cartilaginous

rings.

The posterior wall of the trachea and main bronchi is membranous and

does not contain cartilage, which is important for the imaging differential

diagnosis, as will be discussed later.

The inner lining of the airways consists

of respiratory ciliated epithelium interspersed with goblet cells, minor

salivary glands and neuro-endocrine cells.

Furthermore, the airways contain

muscle tissue, cartilage, nerves, etc.

All of which may give rise to pathology.

Differential diagnosis

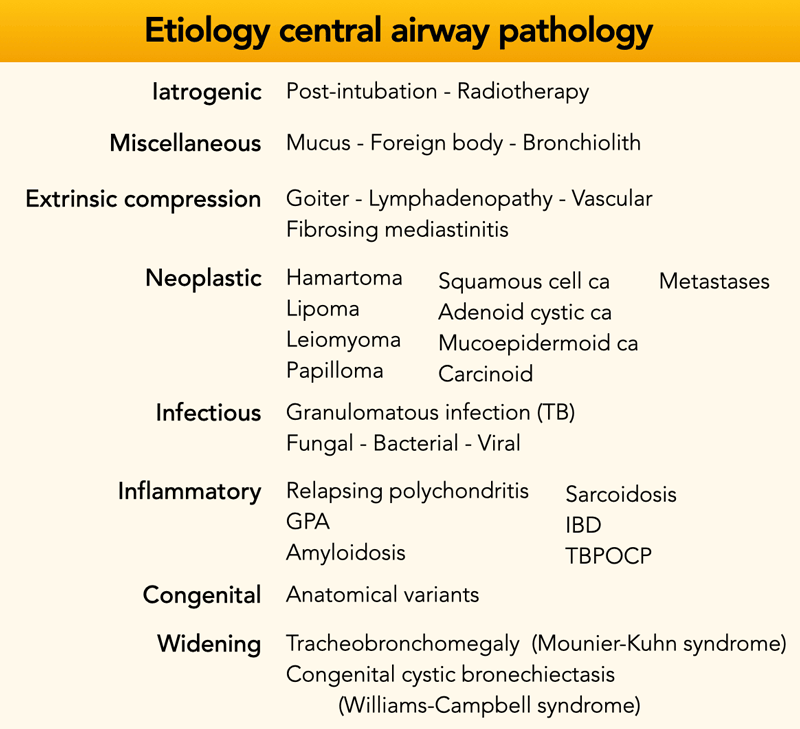

Central airway pathology can be divided into subgroups, either by etiology (ie. inflammatory, neoplastic, etc.) or by imaging appearance (ie. nodular, single/multifocal, diffuse infiltration, etc.).

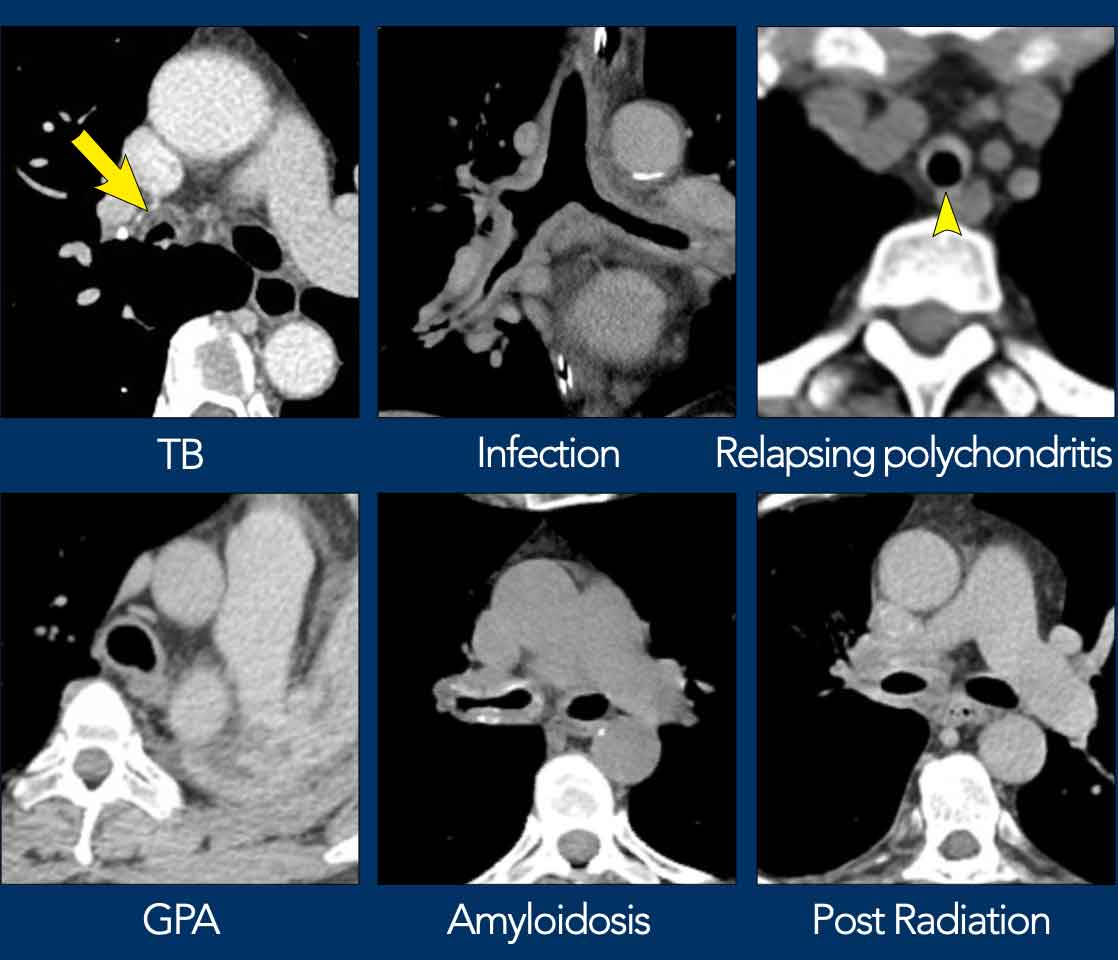

In the table an overview based on disease etiology subgroups to provide a comprehensive overview.

- TB = tuberculosis

- GPA = granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- IBD = inflammatory bowel disease

- TBP-OCP = tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica

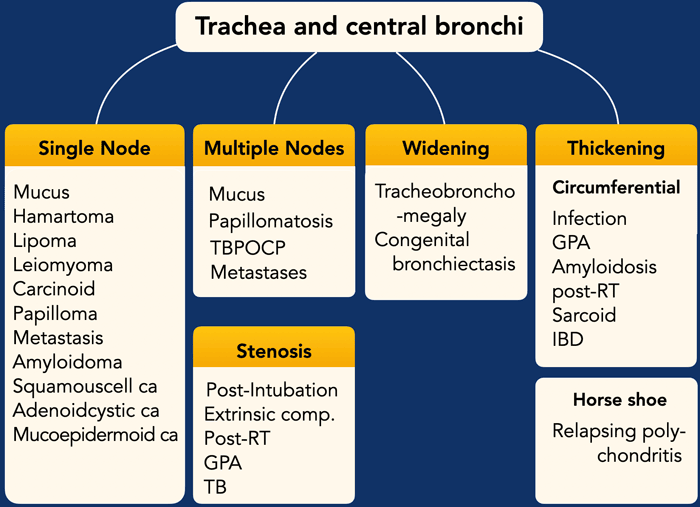

This is a flow-chart that is based on imaging appearances, which can be used to narrow down the differential diagnosis.

Nodular - differential

Nodular

lesions protrude into the lumen and distort the smooth inner contour of the

airway.

Only a minority of these lesions will have specific morphologic

features.

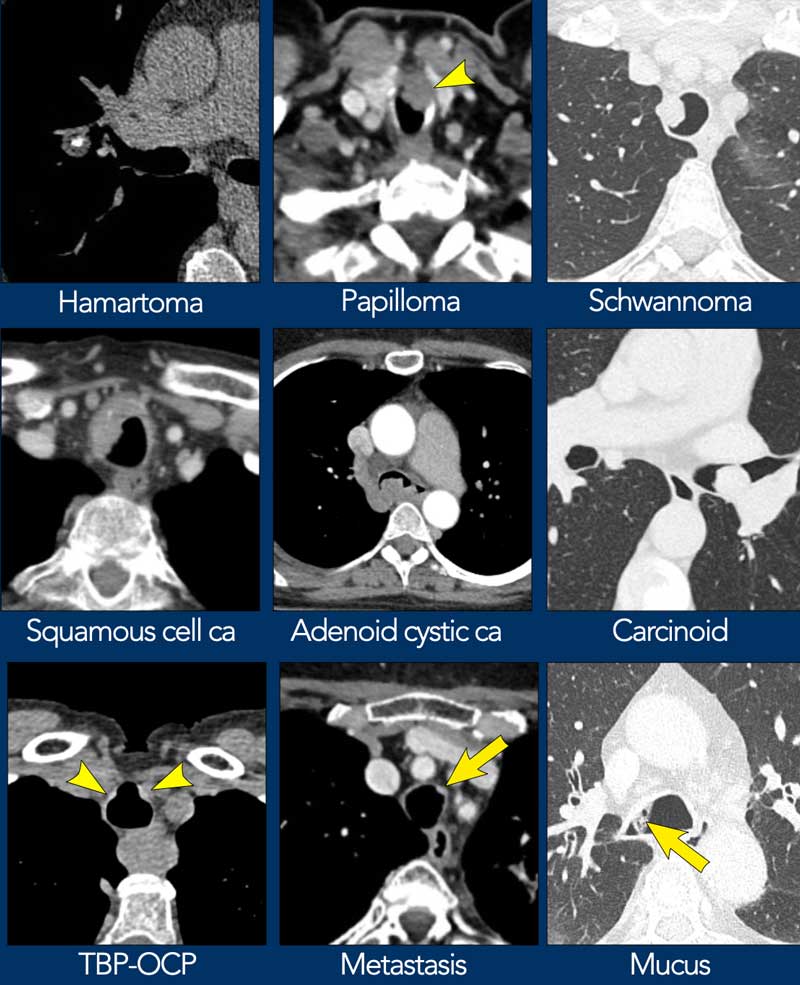

Here some examples of nodular or mass lesions in the trachea and

bronchi.

- Squamous cell carcinoma usually has a destructive pattern with invasion of surrounding structures.

- Carcinoid is a well circumscribed endobronchial lesion, that rarely involves the trachea.

- Macroscopic fat may be seen in either hamartoma or lipoma.

- Mucus has low density and is usually only seen in lung window settings.

Wall thickening - differential

At the site

of involvement there is loss of the normal smooth and thin contour of the

tracheal and bronchial wall.

Only a few diseases have specific morphologic

features.

Here some examples of both focal and diffuse central airway wall

thickening.

- Relapsing polychondritis has a characteristic horseshoe shaped appearance.

- Amyloidosis shows a strikingly irregular pattern with calcification, virtually pathognomonic.

- Radiotherapy effect is limited to the radiation field.

Iatrogenic

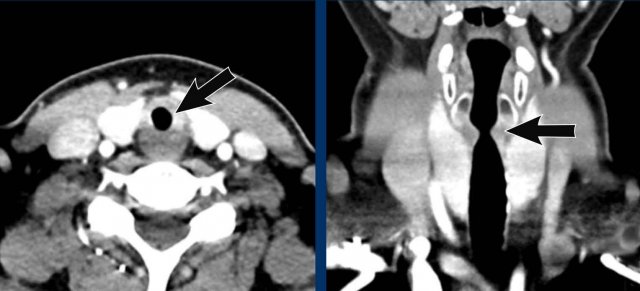

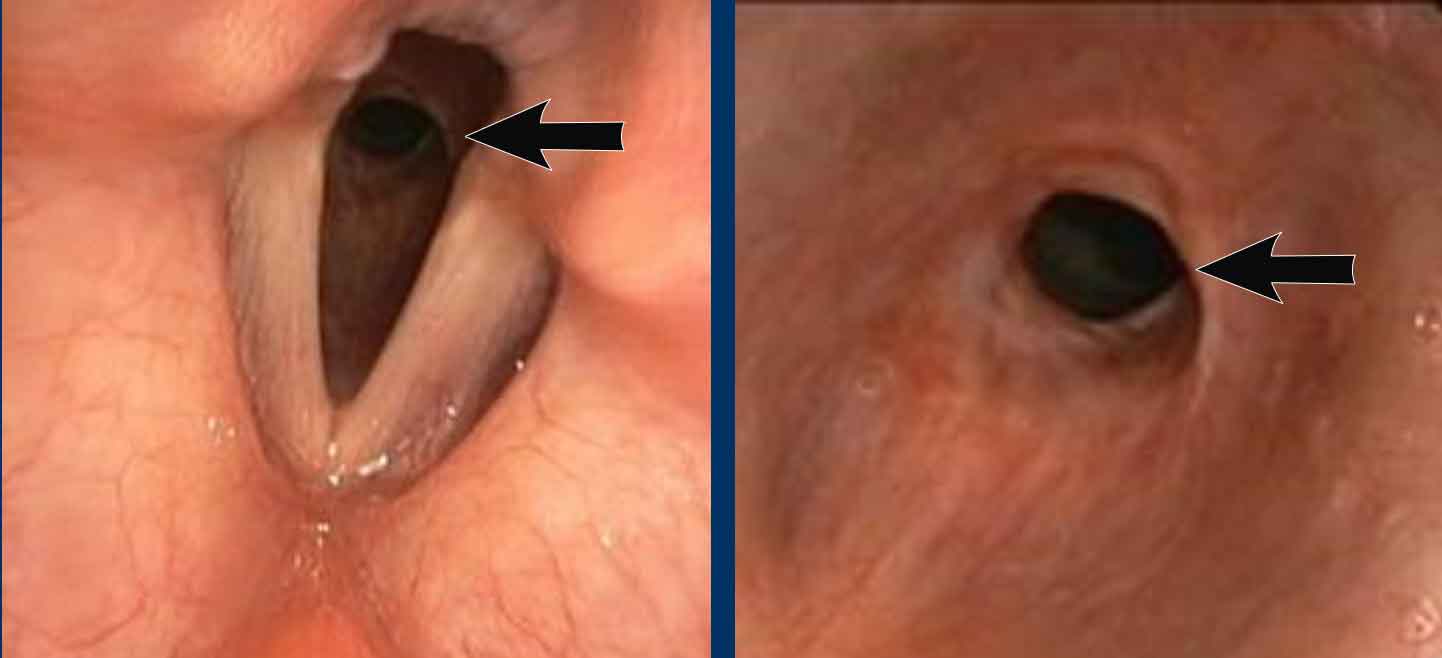

Post-intubation

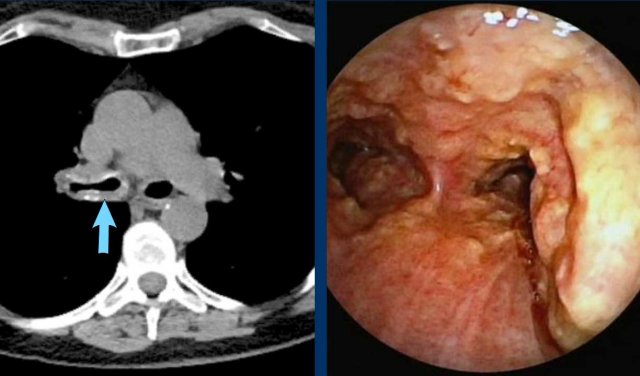

The most common iatrogenic central airway pathology is focal stenosis after endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy. Focal fibrosis may occur in reaction to necrosis caused by cuff pressure or due to direct iatrogenic damage of the tracheal wall.

Typically, a subglottic stenosis near the thoracic inlet is seen with an hourglass shape in the coronal plane, due to a short segment of focal scarring in the trachea (figure).

Bronchoscopy images from above and below the level of the vocal cords, show a significant subglottic narrowing of the trachea.

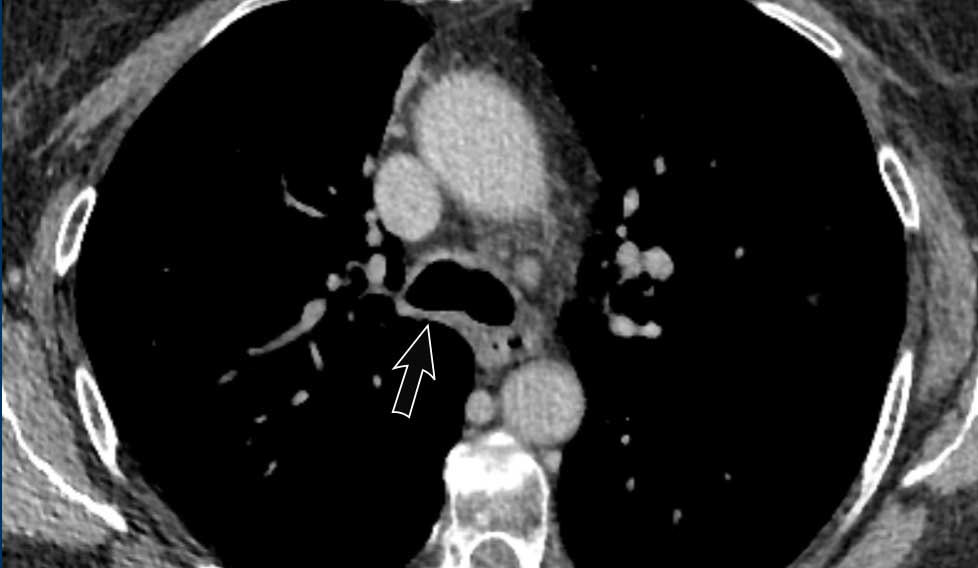

Radiotherapy

When applied to tumors in proximity to

the central airways radiotherapy can cause airway narrowing, fistula, necrosis and sometimes massive hemoptysis.

In addition mediastinal fatty

infiltration and esophageal wall thickening may be present in the acute phase.

Image

Wall thickening of the trachea bifurcation post-radiotherapy.

Foreign body

Aspiration of a foreign body is rare in adults, and most often encountered in children.

Among adults aspiration of dental parts is relatively common, especially in the trauma population. Conventional imaging after aspiration may not show a radiopaque foreign body, depending on material composition.

Indirect signs might be present though, for example unilateral hyperinflation or lung atelectasis due to check valve mechanism and obstruction, respectively.

Image

Aspiration of device during dental surgery, visible in the right lower lobe bronchus.

Bronchiolith

Endobronchial calcification which may be caused by

calcification of aspirated foreign material, or migration or erosion and

extrusion of adjacent calcified material from for example a lymph node or

ossified bronchial cartilage.

Mucus

The most encountered focal abnormality in the trachea is mucus.

In large quantities it can cause bronchial obstruction and atelectasis, especially in the ICU setting.

In most cases it represents an irrelevant finding, but small quantities sticking to the airway wall may create a diagnostic dilemma.

In general mucus may show an associated mucus thread and is often not dense enough to be seen on the soft tissue reconstruction windows.

When in doubt whether focal airway wall pathology is present, follow-up imaging or bronchoscopy might be considered.

Mucus will resolve or change position on follow-up CT imaging, whereas a solid lesion persists.

Extrinsic compression

Enlarged goiter

Intrinsic versus extrinsic pathology is one of the first differentiations that has to be made when interpreting CT imaging.

The most common cause of extrinsic compression is intrathoracic extension of an enlarged thyroid, causing displacement of the trachea more than narrowing.

Other mediastinal causes are:

- Thoracic aorta aneurysm.

- Anatomical variant of the great vessels (eg. double aortic arch), usually in young patients.

- Bulky lymphadenopathy or mass.

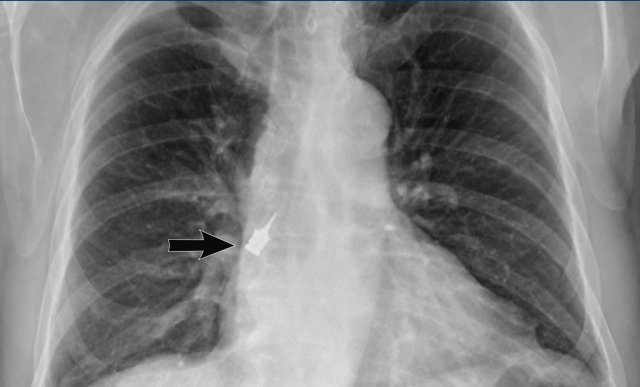

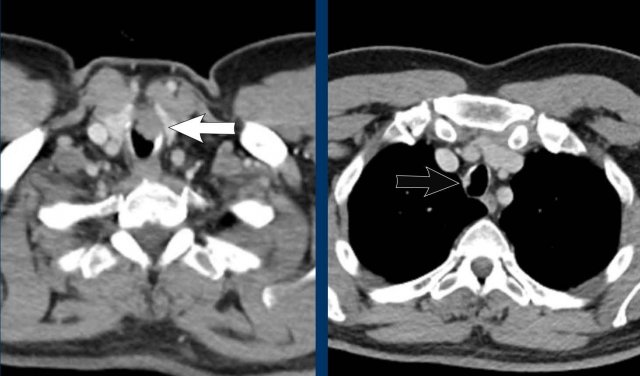

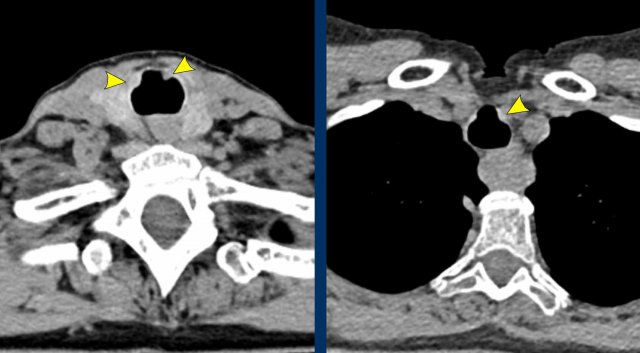

Lymph nodes

Compression of the right main bronchus by enlarged lymph nodes.

Double aortic arch

This patient has a double aortic arch which compresses the trachea.

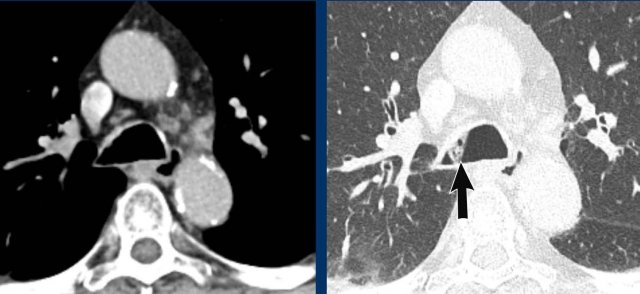

Fibrosing mediastinitis

Fibrosing mediastinitis is a more tricky

cause of extrinsic compression and displacement as it is often hard to diagnose

with certainty.

On CT imaging it can show considerable overlap with findings of

airway involvement due to a central lung malignancy.

Repetitive negative tissue

sampling and follow-up will often seal the case eventually.

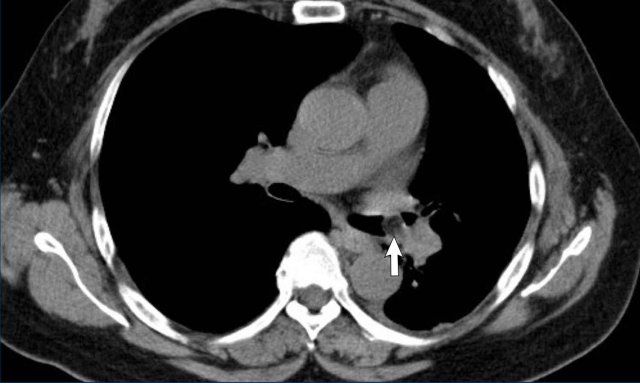

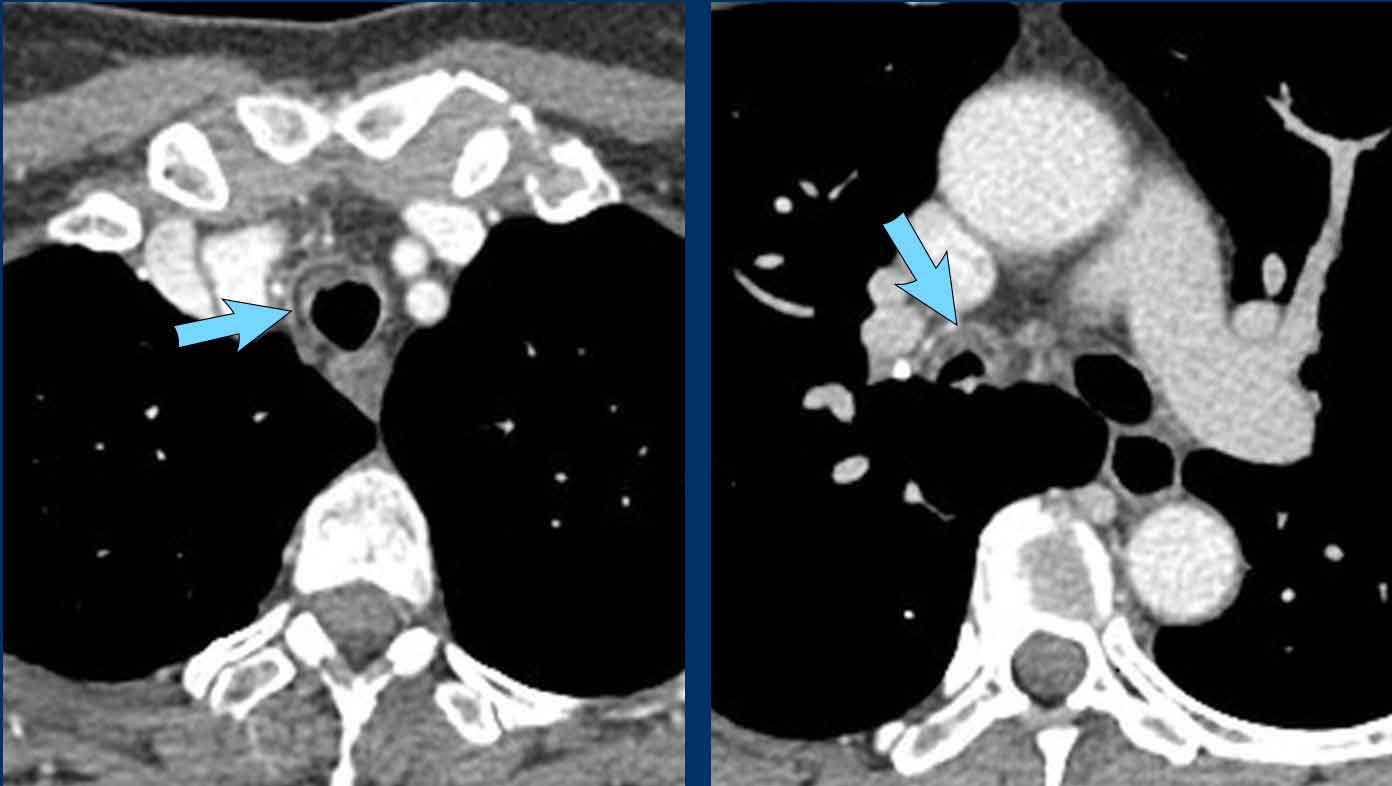

Image

Right-sided fibrosing mediastinitis in a 51 year old male, showing soft tissue density around the right main bronchus (arrow).

Same patient.

There are secondary signs of central airway and vessel

compression, with localized lung volume loss and interstitial thickening due to

edema.

Benign neoplasm

Hamartoma

Hamartoma is a benign lesion that is composed

of various mesenchymal tissues such as chondroid cartilage, fat and fibrous

tissue.

It is the most common benign lung tumor and most often located more

peripherally in the lung parenchyma, but sometimes arises in the airways.

Image

Endobronchial

hamartoma as an incidental finding in the middle lobe of a 73 y.o male.

CT characteristics of a hamartoma are independent of its location:

- Hypodense lesion

- Fat attenuation

- Popcorn calcification (may

be present)

Image

Fat containing hamartoma obstructing the left lower lobe bronchus in a 58 y.o female.

Lipoma

Typically seen as an endoluminal lesion without soft tissue component due to its pure fatty nature. It arises from the submucosal fat tissue of the tracheobronchial tree. The lesion is often pedunculated, although this is not always evident on CT.

Leiomyoma

Leiomyoma arise from the smooth muscle cells of the trachea. Typically it is seen as an endoluminal mass in relation to the posterior wall. The lesion may show heterogeneous density due to cystic degeneration as a result of poor vascularity.

Papilloma

A squamous cell

papilloma is the solitary variant of tracheobronchial papillomatosis, where

papillomatous growth of the epithelium is a response to HPV infection.

Laryngeal involvement is more common than tracheobronchial disease and when

central airway involvement occurs it may be seen on CT as multifocal nodularity not extending beyond the wall, and without calcification.

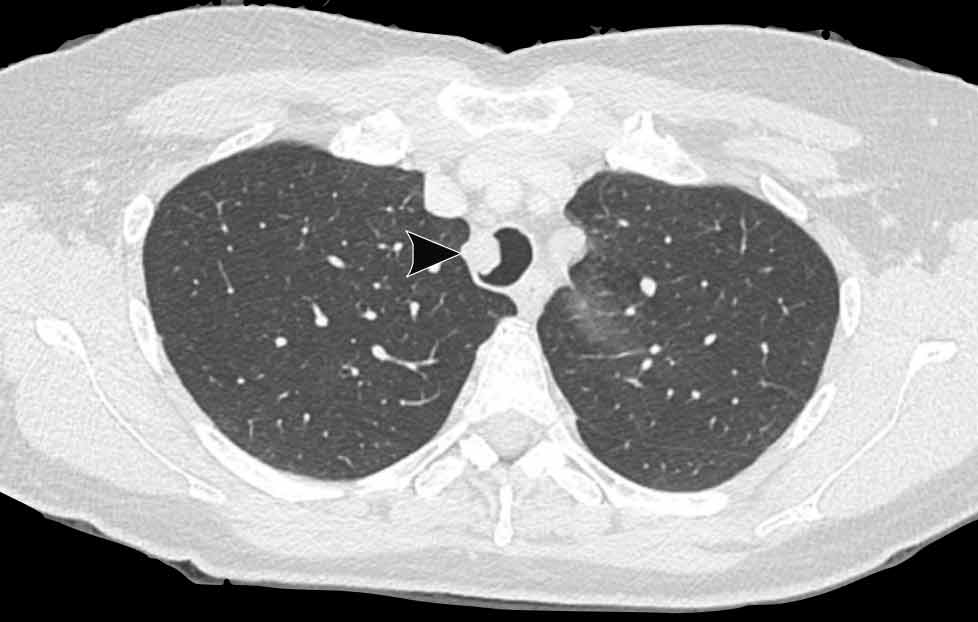

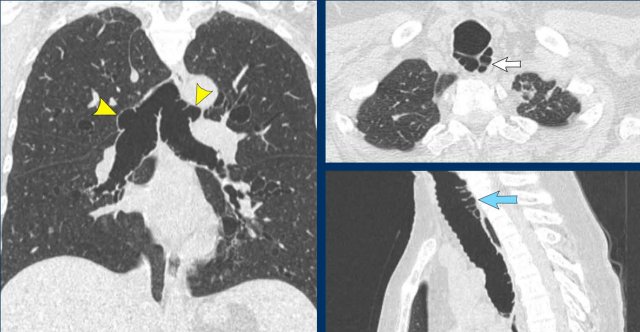

Image

Tracheobronchial

papillomatosis with lung involvement in a 54 y.o male, showing two papillomas

in the trachea.

Continue with the lung window...

The image shows multiple cystic lesions in both lungs (arrowheads).

In rare cases extension into the lung parenchyma can occur, showing cystic nodules most often in the dependent apical segments of the lower lobes. There is a small risk of malignant transformation from squamous cell papilloma into squamous cell carcinoma.

Miscellaneous

Given that any cell type present in the

central airways may give rise to pathology, all kind of rare lesions can develop.

This includes for example neurogenic tumors (figure) and rare lesions such as inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor.

Malignant neoplasm

Several primary malignant lesions arise in

the central airways.

Often they cause respiratory symptoms, and sometimes

hemoptysis.

In line with the benign neoplastic lesions, a specific radiological

diagnosis is challenging.

Patient characteristics such as age, smoking history,

as well as lesion morphology and location may give clues and will influence the

order of differential diagnostic considerations.

Given that any cell type present in the

central airways may give rise to pathology, all kind of rare lesions

develop.

This includes for example malignant lesions such as chondrosarcoma.

Radical surgical resection is

the preferred treatment, but often technically impossible.

Depending on the histology

and stage of the tumour, other modalities such as chemoradiotherapy may be used

with curative intent.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common primary

malignancy of the trachea.

Generally, it occurs in older patients with a

substantial smoking history.

Typically, an irregular mass is seen that tends

to invade surrounding tissues outside the airway wall.

Image

Irregular

focal mass that invades the trachea wall and peritracheal tissue in a 66 y.o

male.

PA:

Squamous cell carcinoma.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) is the next most common

primary malignancy of the central airways.

Contrary to squamous cell carcinoma there is no association

with smoking.

Patients also tend to be younger, mostly middle-aged.

Radiologically adenoid cystic carcinoma can present as either a:

- focal mass

- more diffuse infiltrating morphology with a long segment of submucosal involvement.

Image

Severe luminal narrowing by a focal mass in 48 y.o female.

PA: Tracheal adenoid cystic carcinoma.

The malignancy arises from the submucosal minor salivary glands, as does the less common mucoepidermoid carcinoma (see below).

The tumor is mostly very centrally located.

The most common sites for metastases are the lung parenchyma and the liver.

Image

Irregular

more diffusely infiltrating mass with long segment of wall thickening invading the mediastinum in a 51 y.o female.

PA:

adenoid cystic carcinoma.

Bronchoscopic view of obstructing tracheal adenoid cystic carcinoma.

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC)

As mentioned above, MEC is a tumour that arises from the submucosal minor salivary glands. It is found in younger patients - often younger than those with ACC - and has no known association with smoking. It has a predilection for the more distal airways, as they are found more often in the segmental/lobar airways and rarely in the trachea. CT imaging features are non-specific; an enhancing focal soft tissue mass, with varying degrees of heterogeneity. Some show internal calcification. Post-obstructive changes may be present.

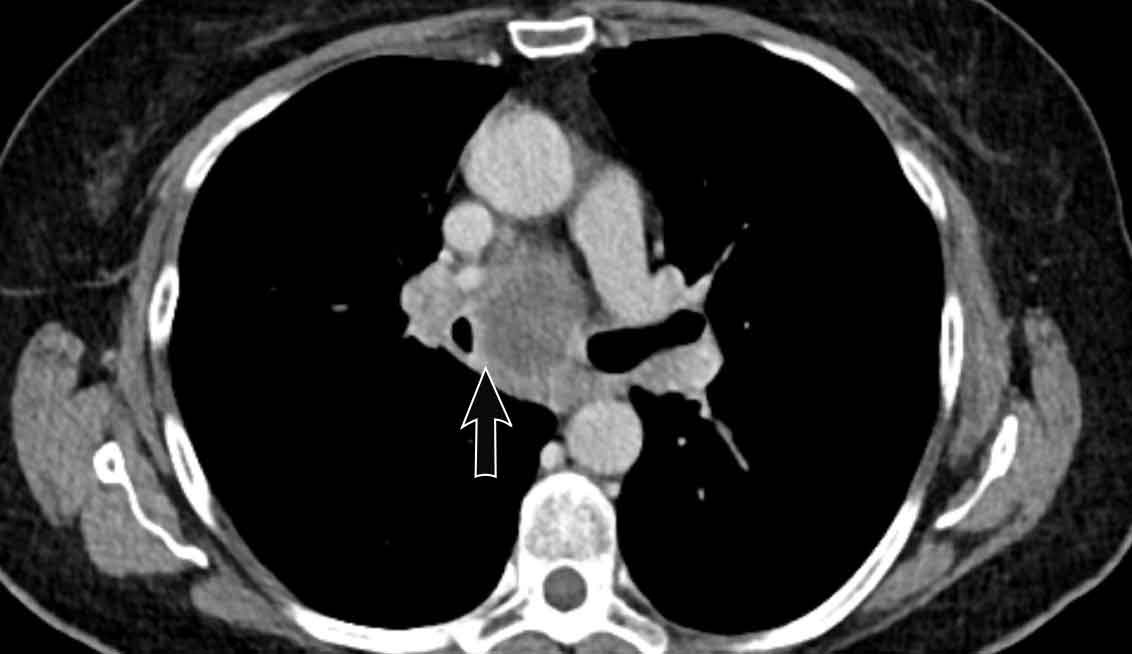

Carcinoid

Carcinoid tumours are low-grade

neuroendocrine tumours (NET) that originate from the neuroendocrine cells in

the airway wall.

Histopathologically, they may be typical or atypical, depending

on the mitotic rate and the presence of focal necrosis.

The majority are

typical carcinoids though, and these behave quite indolent.

They are found in

both younger and older patients, and there is no association with smoking.

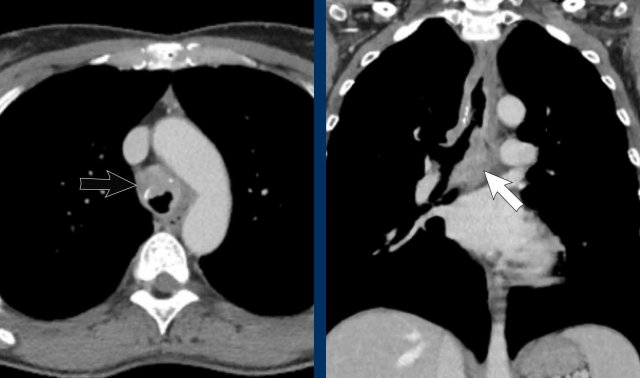

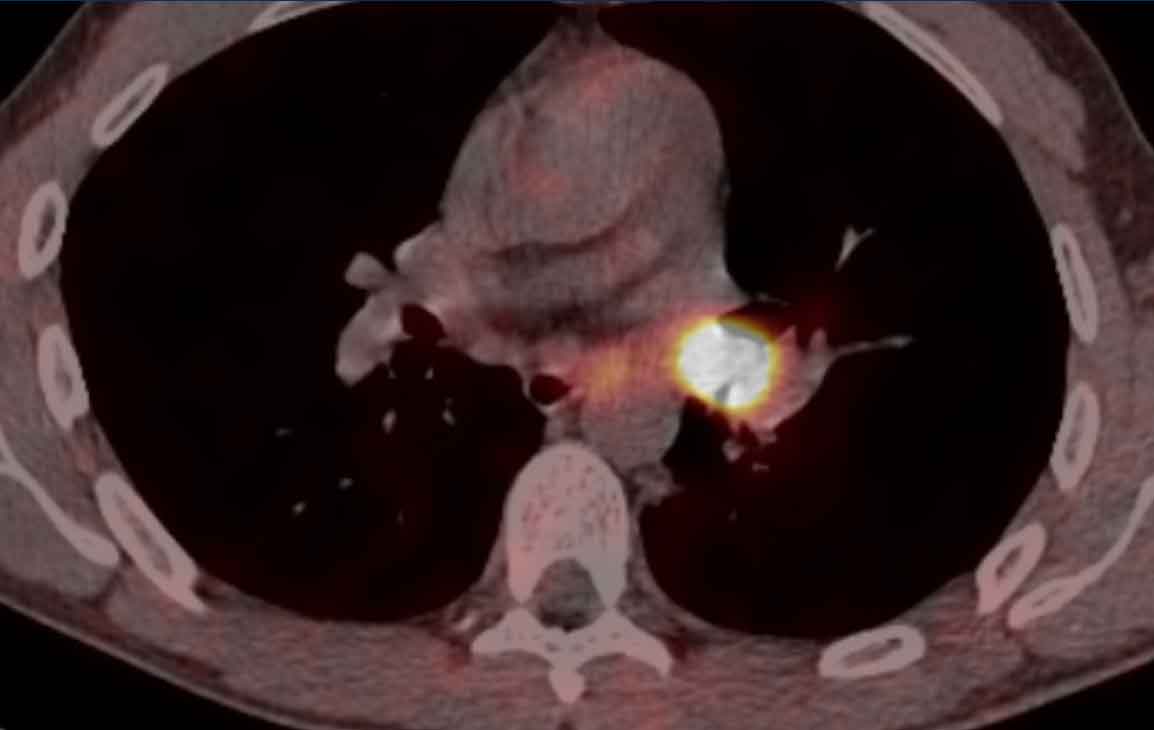

Image

Well-defined mass in the left main

bronchus in a 39 year old male.

Continue with the PET-CT...

The 68Ga-Dotatate PET-CT shows vivid uptake confirming the neuroendocrine cell origin.

Carcinoids arise in the more central airways (although hardly

ever in the trachea) as well as in the more peripheral ones, all the way

towards the outer third of the lung.

On CT carcinoid is a well-defined lesion, often hyperdense on post-contrast CT given their hypervascular nature.

Calcifications may be present in a minority.

Post-obstructive changes are common due to luminal obstruction, and may be the reason it is found.

Some lesions also show an extraluminal component, which excludes the option of complete curation through an endoscopic procedure.

Anatomical surgical resection is needed in these cases.

Continue with the bronchoscopic view...

Bronchoscopic view showing the typical finding of a well-defined and

vascularized lesion obstructing the lower lobe orifice.

PA: Carcinoid.

Metastases

Metastatic disease to the

central airways does occur through distant hematogenous or lymphatic spread.

Although uncommon, it is sometimes seen for instance in breast carcinoma, renal cell cancer and colorectal carcinoma.

Imaging findings are nonspecific and may show single or multiple solid nodules

projecting into the airway lumen.

Larger and more peripheral lesions may cause

airway obstruction.

Usually airway metastatic disease is not an isolated finding, but seen in patients with known metastatic disease.

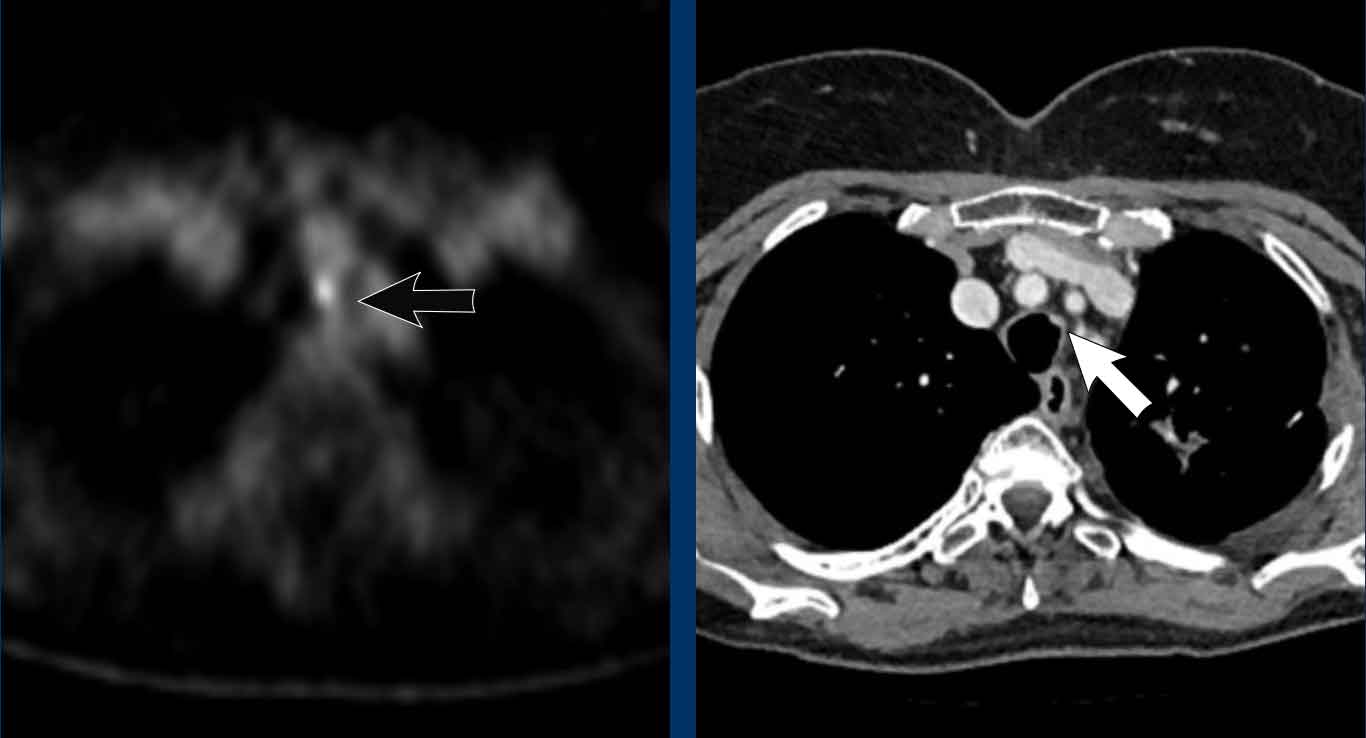

Image

The PET-CT shows high uptake corresponding to a small nodular

lesion in the proximal trachea in a 52 y.o female with prior colorectal

cancer.

PA: metastasis of colorectal cancer.

Infection

TB

As with most other infectious diseases, pathogens causing tracheobronchial infection can be either bacterial, fungal or viral.

Community acquired bronchitis is mostly triggered by a viral infection. Sometimes infection may be associated with procedures such as tracheostomy, as shown on the left.

Although tuberculosis can cause central airway

abnormalities, isolated tracheobronchitis is very rare.

Central airway involvement during more widespread thoracic

disease is more likely, and can reveal itself on CT imaging as irregular focal

or more diffuse wall thickening.

In the chronic phase it may lead to focal

airway stenosis due to airway remodelling and formation of fibrosis in reaction

to ulceration of submucosal tubercles.

Image

Focal wall thickening with luminal narrowing of the trachea and right main bronchus in a 63 y.o female with remote TB infection. Biopsy showed fibroelastic scarring.

Fungal infections causing tracheobronchitis might also be encountered, for example by Aspergillus, Candida or Histoplasmosis.

This occurs primarily in the immunocompromised population.

In line with the above mentioned TB morphology, it may cause non-specific CT findings of focal or more diffuse wall thickening, with residual scarring and stenosis in later stages of the disease.

Image

Diffuse

circumferential wall thickening of the trachea and central bronchi with

uptake on FDG-PET scan (blue arrow) in a 72 y.o male after tracheostomy due to

complicated thyroidectomy.

Clinically labelled as low-grade infectious,

despite the fact that no specific pathogen was cultured.

Inflammatory

Relapsing polychondritis

Relapsing polychondritis is an auto-immune disorder that affects

the cartilage in the central airways with recurrent episodes of inflammation

and possible destruction and fibrosis.

As cartilage in other parts of the body

may also be affected, clinically one may see ear and nose involvement as well

(eg. saddle-nose deformity). Cardiovascular disease such as cardiac valve

disease and aortic aneurysm can occur.

On CT imaging of the chest central airway wall

thickening with soft tissue density is seen.

Abnormalities typically spare the

posterior wall which lacks cartilage.

Beyond the acute phase calcification and stenosis may form, as well as

excessive airway collapse in expiration (ie. tracheobronchomalacia) due to

cartilage destruction.

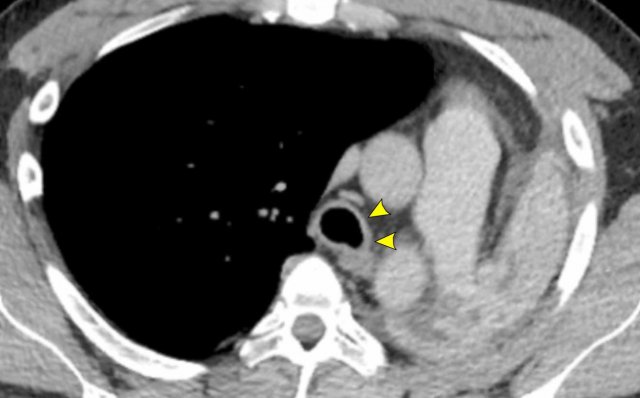

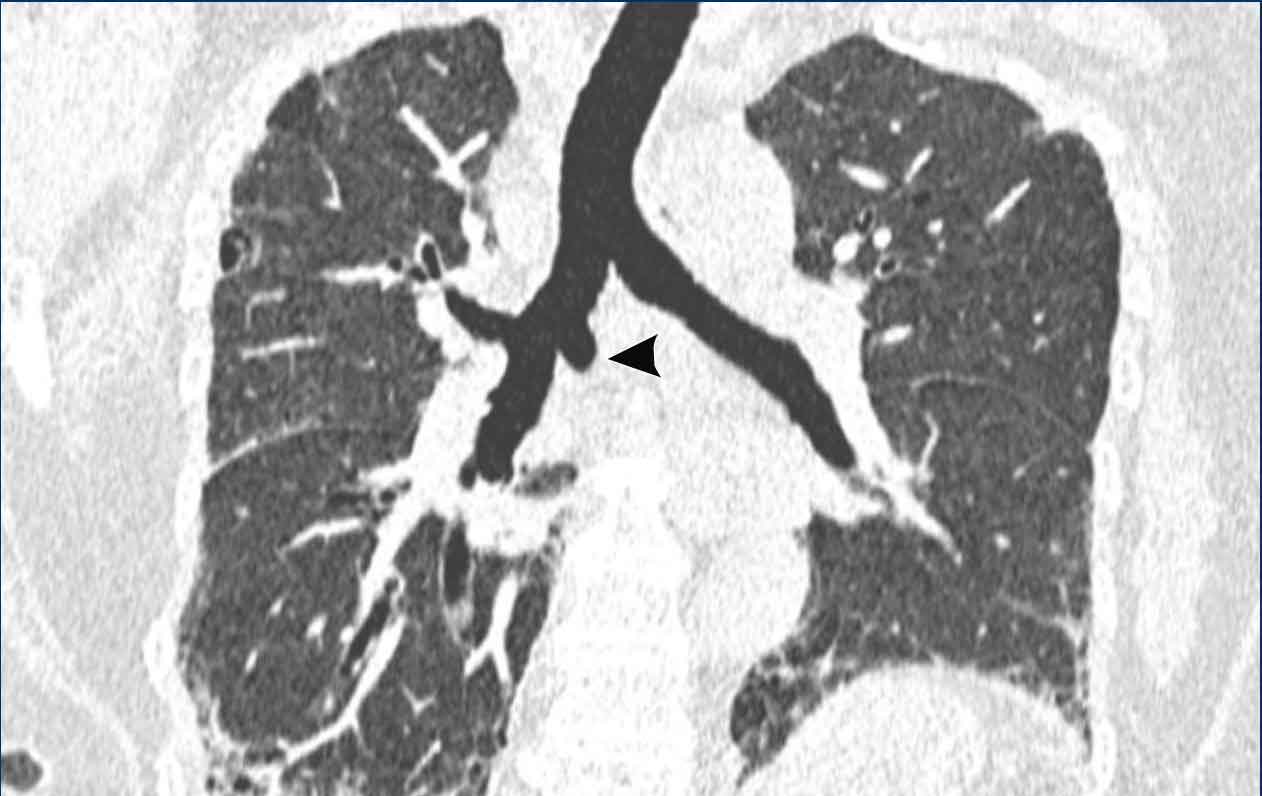

Image

Relapsing polychondritis in a 55 y.o female, showing inflammatory central airway wall thickening with the characteristic horseshoe shaped appearance (arrowhead). No thickening of posterior wall (yellow arrow).

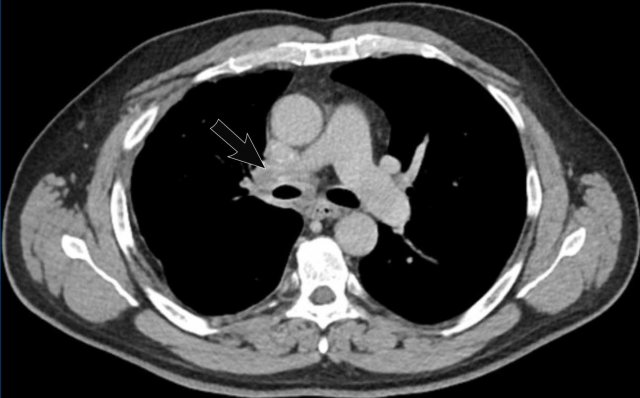

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), previously known as Wegener's granulomatosis, is a

multisystem necrotizing vasculitis that affects the medium and small size vessels with involvement of paranasal sinuses, lungs and kidneys.

Clinically

it is associated with elevated c-ANCA titers.

GPA can cause irregular

circumferential wall thickening of the central airways, which can lead to

stenosis in later stages of the disease.

This is typically seen in the

subglottic trachea but also occurs in the main stem and lobar bronchi.

Synchronous pulmonary findings of cavitating consolidations and ground glass caused by the vasculitis – due to necrosis and alveolar hemorrhage, respectively – are helpful to sort the differential diagnostic considerations.

Image

Central airway involvement in GPA showing circumferential tracheal wall thickening at the level of the carina in a 43 y.o male. There is left lung collapse due to chronic involvement of the left main bronchus with stenosis.

Amyloidosis

Tracheobronchial amyloidosis is characterized by submucosal

deposition of abnormal amyloid protein.

It is a very rare disease, which is

usually isolated but can be associated with systemic amyloid disease.

The protein deposition can either be focal (ie. mass-like;

amyloidoma) or more diffuse and infiltrative.

Amyloid in the airway walls leads

to dense and calcified, strikingly irregular soft tissue thickening on CT

imaging.

There is no cure, and therapeutic options such as external beam

radiation and bronchoscopic debulking are focussed on limiting luminal

obstruction to relieve respiratory symptoms.

Image

Tracheobronchial amyloidosis in a 61 y.o

female, showing irregular airway wall thickening with dense and calcified foci causing

significant luminal narrowing of the right main bronchus.

Bronchoscopy

shows typical yellowish irregular lesions.

Sarcoidosis

The most common manifestations of sarcoidosis in the chest

are symmetrical hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy and pulmonary parenchymal

involvement with lymphatic distribution of small nodules.

This imaging

morphology is classic, but the disease is known for its wide range of

appearances and may be considered in the differential diagnosis for a lot of

imaging findings.

Although histopathologically granulomatous involvement of the

airways is relatively common, CT signs of central airway involvement in

sarcoidosis are relatively rare.

Of course, architectural distortion and airway

obstruction may be caused by extrinsic compression due to peribronchial fibrosis, which is often seen in the

hilar regions.

In addition, direct airway remodelling due to granulomatous involvement

of the central airways may lead to circumferential airway wall thickening.

If

present, it is almost always part of more extensive thoracic disease and not an

isolated finding.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

Both

ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) may show airway involvement.

More common than central airway disease is peripheral bronchial wall thickening

and bronchiectasis, as well as signs of involvement of the smaller airways (ie.

bronchiolitis and air trapping).

When

the trachea and main bronchi are involved, CT imaging may show nonspecific

circumferential wall thickening, luminal narrowing and postobstructive

findings.

Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica

The etiology of this disease is not well known.

It is

characterized by submucosal osteocartilaginous nodules that on CT imaging

present as multiple small calcified nodules that only involve the cartilaginous

portion of the central airways, and thus spares the posterior wall of the

trachea.

This disease may be an incidental finding, but may also

cause mild respiratory symptoms.

The prognosis is generally good and in

asymptomatic cases no interventions are needed.

If needed, therapeutic options may be focussed on limiting luminal obstruction caused

by the osteocartilaginous nodules.

Image

Tracheobronchopathia

osteochondroplastica in a 67 y.o female with non-specific airway symptoms,

showing multiple small nodules along the cartilaginous part of the trachea

Congenital

Tracheal bronchus

Airway branching variation is very common, especially at

the segmental level.

Several anatomical variants are encountered on a more

regular basis and might be worth mentioning, although patients are mostly asymptomatic.

If

they do lead to symptoms, this is mostly due to recurrent infections caused by abnormal

drainage.

In case of a tracheal bronchus (also called pig bronchus) the right upper lobe parenchyma is partially aerated through a separate bronchus that originates directly from the supracarinal portion of the trachea.

Image

Incidental tracheal

bronchus in a 28 y.o male scanned for oncology follow-up (axial image) and in a 77 y.o male scanned in trauma setting (coronal image).

Cardiac bronchus

This truly supernumerary bronchus

originates on the medial side of the bronchus intermedius, opposite to the

right upper lobe orifice.

This might be a blind ending structure, or an airway

that aerates a small amount of lung parenchyma.

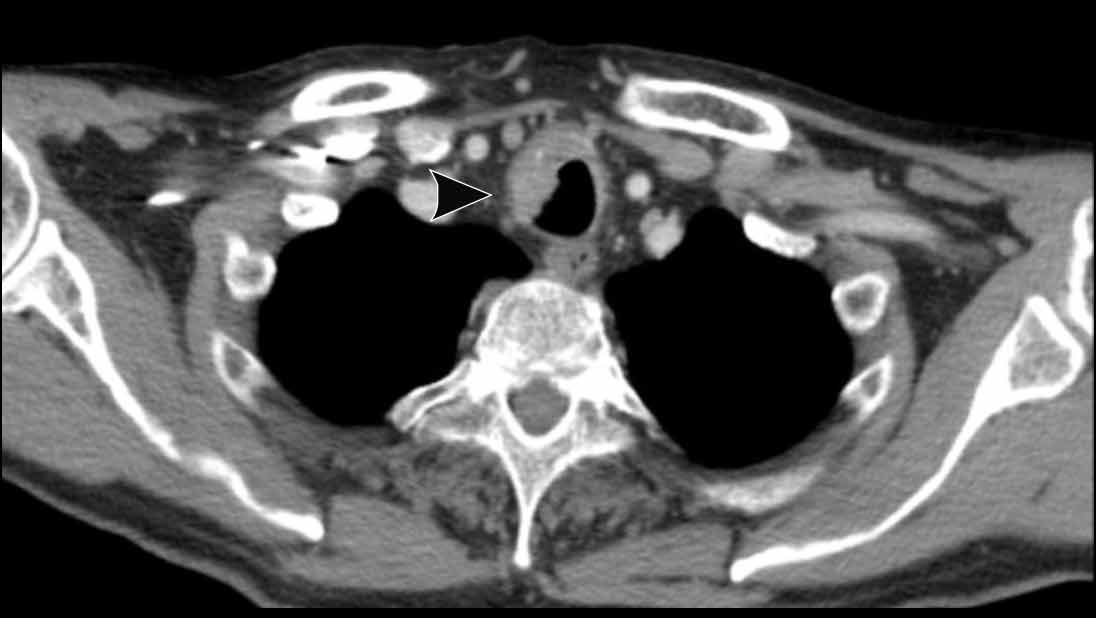

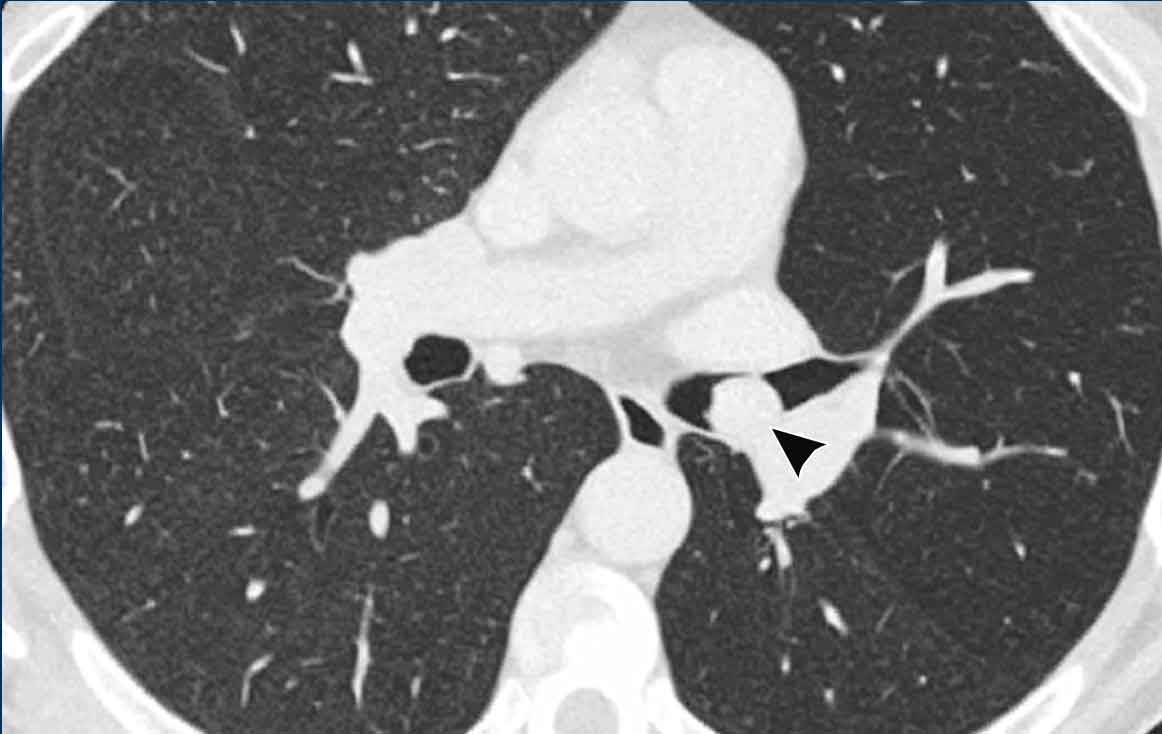

Image

Cardiac

bronchus (arrowhead) in a 57 y.o female in follow-up for interstitial lung disease.

Tracheobronchomegaly in a 59 y.o female, showing a severely dilated trachea and mainstem bronchi, with evident posterior diverticulosis.

Tracheobronchomegaly in a 59 y.o female, showing a severely dilated trachea and mainstem bronchi, with evident posterior diverticulosis.

Tracheobronchomegaly

Tracheobronchomegaly (also called Mounier-Kuhn syndrome) is caused by

abnormal elastic fibres and smooth muscle cells in the central airways.

Typically, it is seen in middle aged men who present with

chronic cough and/or recurrent infections.

CT findings:

- Enlargement of central airways in inspiration (trachea > 3 cm)

- Due to the flaccidity of the airways, marked collapse in expiration.

- Posterior tracheal diverticulosis

- Central bronchiectasis

Williams-Campbell syndrome

This

disease is characterized by congenital cystic bronchiectasis, and typically

presents with recurrent infections.

It is thought to be caused by cartilage

deficiency in the subsegmental bronchi (ie. 4th to 6th order).

It therefore shows bilateral diffuse

bronchiectasis on CT imaging, with typical sparing of the lower order bronchi

and trachea.

This in contrast to

tracheobronchomegaly that typically involves the 1st to 4th order bronchi.

Image

Localized perihilar bronchiectasis but normal dimensions of the trachea, main bronchi as well as peripheral airways.

This was a 46 y.o male with the

diagnosis of Williams-Campbell syndrome, presenting with recurrent infections,

mild hemoptysis and longstanding airway symptoms.