Endometriosis - MRI detection

Jan Hein van Waesberghe, Marieke Hazewinkel and Milou Busard

Radiology department of the VU University Medical Center Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

Laparoscopy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis.

MRI is helpful in determining the extent of deep infiltrating endometriosis, especially when laparoscopic inspection is limited by adhesions.

In this article we will focus on the diagnosis and preoperative assessment of endometriosis using MR imaging.

You can enlarge images by clicking on them.

This item is not available on the iPhone application.

Introduction

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity.

It is mainly found in the abdominal cavity, most commonly on the surface of the ovaries.

It is an estrogen-dependent disease and is estimated to occur in 10% of the female population, almost exclusively in women of reproductive age.

The most common symptoms are dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and infertility - although it may also be asymptomatic.

The symptoms depend on the localization of the endometriosis, the depth of the infiltration and whether the endometriosis is complicated by adhesions.

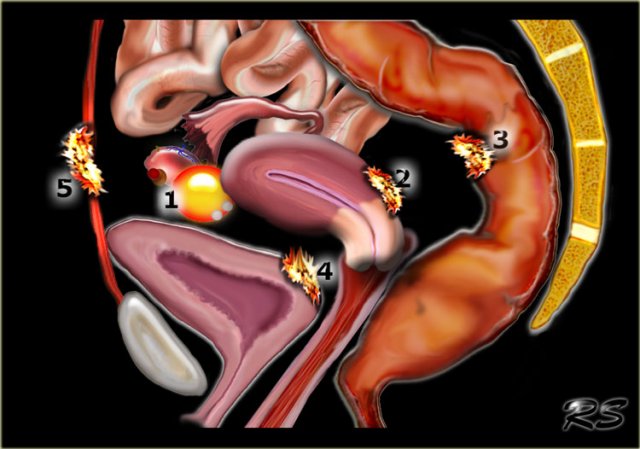

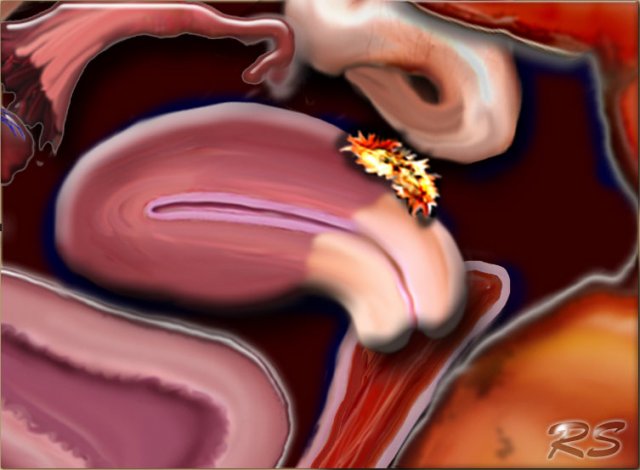

The illustration shows the typical localizations of endometriosis:

- ovarian endometrioma

- retrocervical endometriosis

- deep bowel endometriosis

- bladder endometriosis

- abdominal wall endometriosis

MRI-protocol

If the only reason for performing MRI is to determine the presence or extent of endometriosis, the sequences listed in the table on the left are sufficient.

Lesions usually demonstrate low to intermediate signal intensity on T2- and T1-weighted images.

In some cases punctate foci of high signal intensity are seen on T2-weighted imaging, indicating dilated endometrial glands.

Foci of high signal intensity may be seen on T1-weighted images.

If these foci also have a high signal intensity on T1-weighted images with fat saturation, it indicates the presence of hemorrhage.

T1-weighted images with fat saturation are necessary to differentiate blood in endometriomas from fat in mature cystic teratomas, since both show high signal intensity on T1-weighted images without fatsat.

If the questions that need answering are more diverse, for example in cases of suspected malignancy, T1- and T1-fatsat sequences before and after the administration of intravenous gadolinium may supplement this protocol.

Diffusion-weighted imaging may also be added.

Superficial endometriosis

In superficial endometriosis – also known as Sampson's syndrome – superficial plaques are scattered across the peritoneum, ovaries and uterine ligaments.

These patients tend to have minor symptoms and usually also less structural changes in the pelvis.

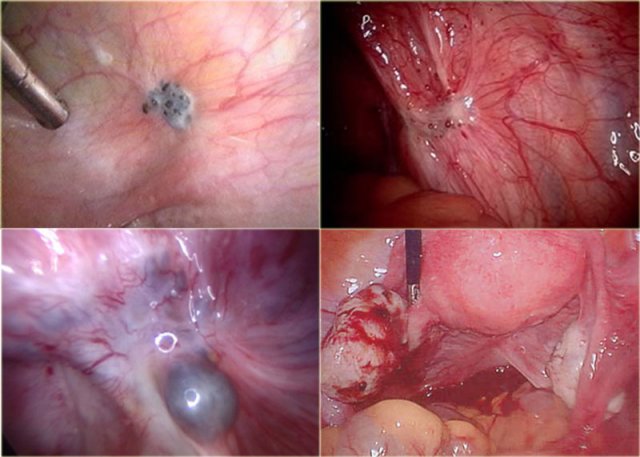

At laparoscopy, these implants may be seen as superficial powder-burn

or gunshot lesions.

On MRI these lesions are most often not visible because they are tiny and flat, and therefore undetectable.

Only when they exceed 5mm or when they appear as hemorrhagic cysts, showing high signal intensity on T1 and low signal intensity on T2-weigthed images, they may be detected (figure).

Neither transvaginal ultrasound nor MRI are sufficiently sensitive to screen for these endometriotic plaques.

Deep pelvic endometriosis

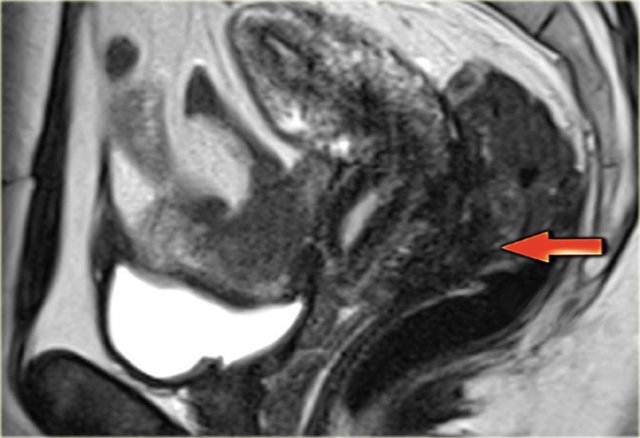

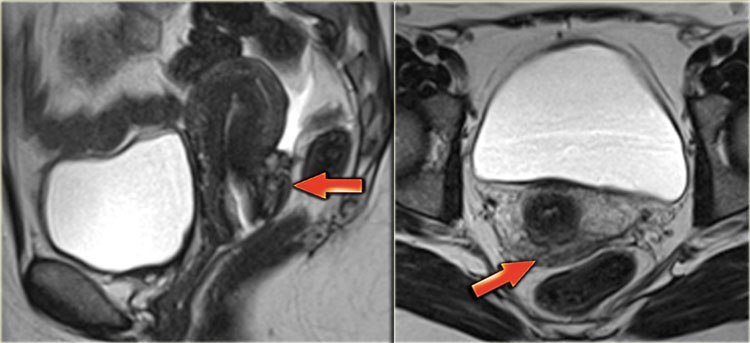

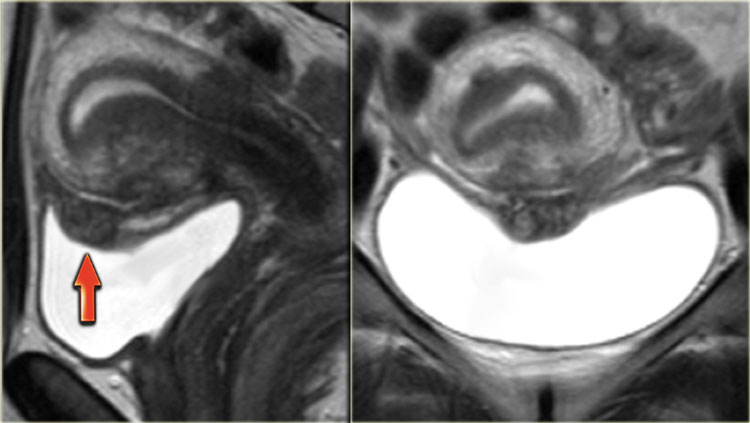

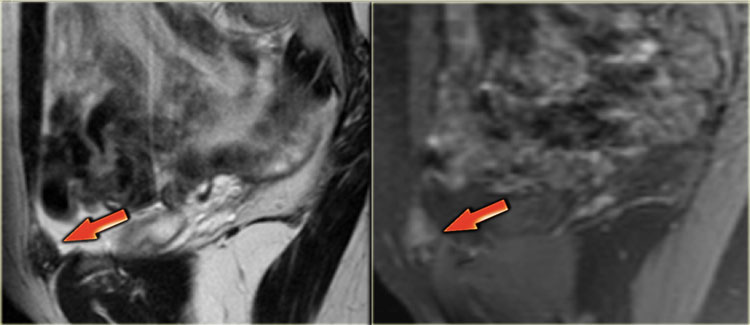

Sagittal T2-weighted images demonstrating endometriosis infiltrating the rectum and endometriosis infiltrating the bladder

Sagittal T2-weighted images demonstrating endometriosis infiltrating the rectum and endometriosis infiltrating the bladder

In deep pelvic endometriosis - also called Cullen's syndrome - there is subperitoneal infiltration of endometrial deposits.

The symptoms are more severe and related to the localization and depth of invasion.

MRI is of use for the diagnosis of deep infiltrating endometriotic lesions and for the assessment of disease extension.

Preoperative mapping of disease extension is important to decide whether surgical intervention is indicated, and if so, for planning complete surgical excision.

Cul-de-sac localization

The cul-de-sac is the most common site of pelvic involvement.

Presence of deep infiltrating endometriosis in the cul-de-sac can be easily overlooked at laparoscopy due to the creation of a false peritoneal floor by endometriosis in the pouch of Douglas, partly caused by anterior rectal wall adhesions.

This phenomenon gives an erroneous impression of extraperitoneal orgin.

Consequently, the location of the deep infiltrating endometriosis in the rectovaginal septum may also be a misnomer as the rectovaginal septum is located caudal to the posterior vaginal fornix and, on the basis of normal anatomy, may therefore not be a primary site for endometriosis to develop.

This differentiation between normal anatomy and the presence of endometriosis in the cul-de-sac is readily made using MRI.

This sagittal T2-image shows deep infiltrating endometriosis in the posterior cul-de-sac with infiltration of the rectal wall.

Uterus

The torus uterinus - where the sacrouterine ligaments attach - and posterior fornix are common localizations of endometriosis.

Clinically these patients often present with dyspareunia.

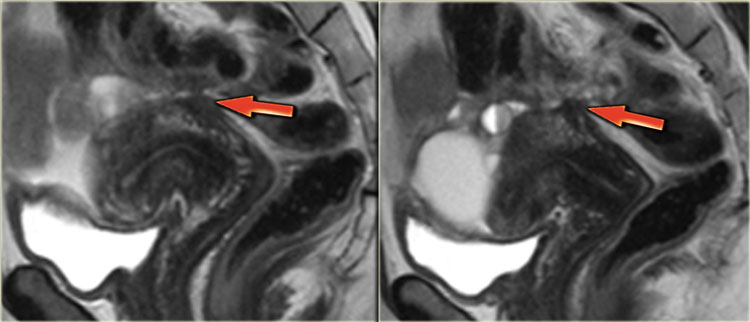

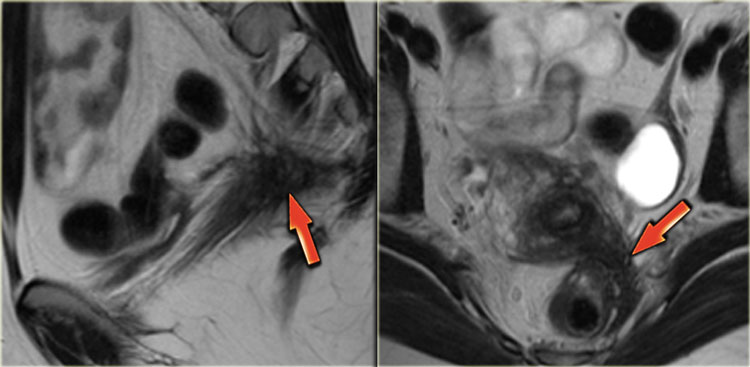

T2-images of endometriosis involving the torus uterinus.

T2-images showing deep infiltrating endometriosis in the posterior fornix and torus uterinus.

There is no infiltration of the bowel wall.

T2-weighted images demonstrating involvement of the left sacrouterine ligament.

Bowel involvement

Bowel endometriosis affects between 4% and 37% of women with endometriosis.

Transvaginal ultrasonography is the first line of investigation in patients with suspected bowel endometriosis.

Additionally, MRI can determine the depth of bowel wall infiltration, the length of the affected area and the distance of the lesion from the anus.

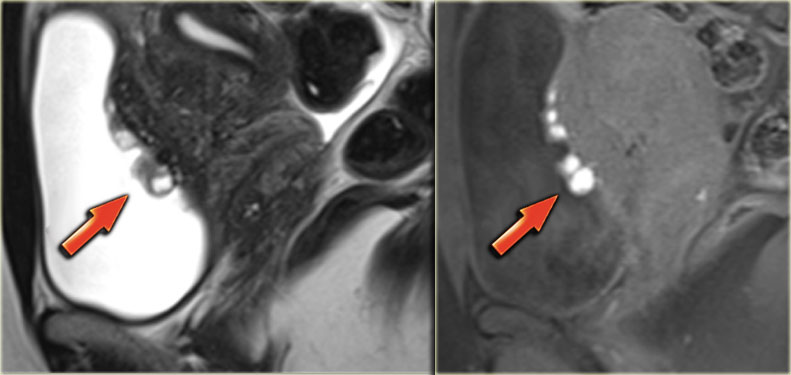

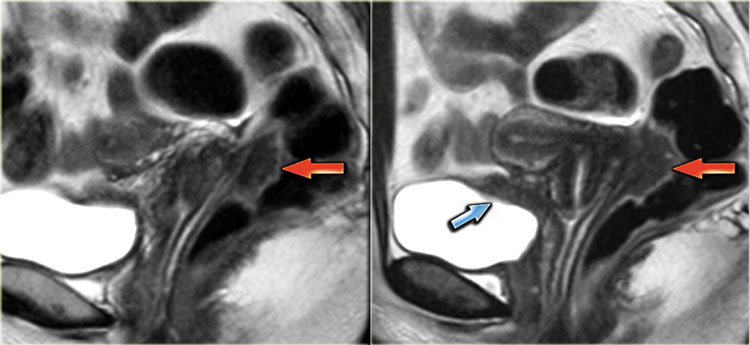

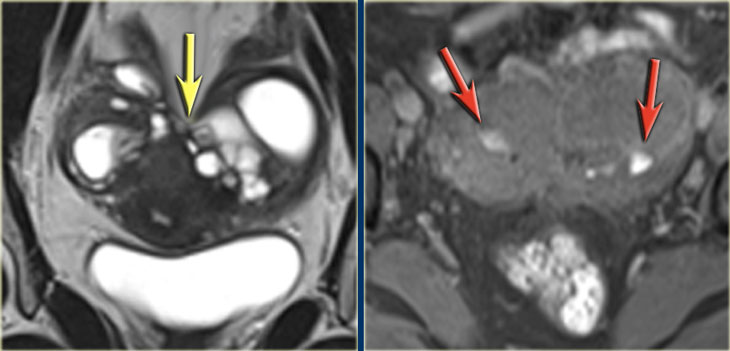

The T2-images demonstrate two fan-shaped hypointense lesions (red arrows).

These findings are typical for endometriotic lesions infiltrating the muscular layer of the bowel wall.

There is also some submucosal swelling, seen as hyperintensity on the luminal side of the bowel wall.

In case of circular involvement, extensive deep infiltrating endometriosis of the bowel wall can lead to stenosis of the bowel lumen.

Patients may clinically present with pencil-like stool or constipation.

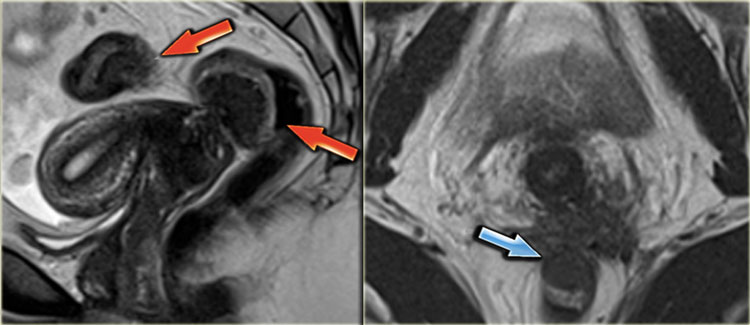

The T2-images show focal stenosis of the rectum as a result of circular endometriotic involvement.

Bladder involvement

The urinary tract is involved in only 4% of women with endometriosis of which around 90% involve the bladder.

The T2-images show endometriosis infiltrating the bladder wall.

The sagittal T2-image shows full-thickness bladder endometriosis with isointense signal compared to muscle and foci of high signal intensity, indicating dilated endometrial glands.

The fatsat T1-image shows small cysts with hyperintense signal within the lesion caused by hemorrhage.

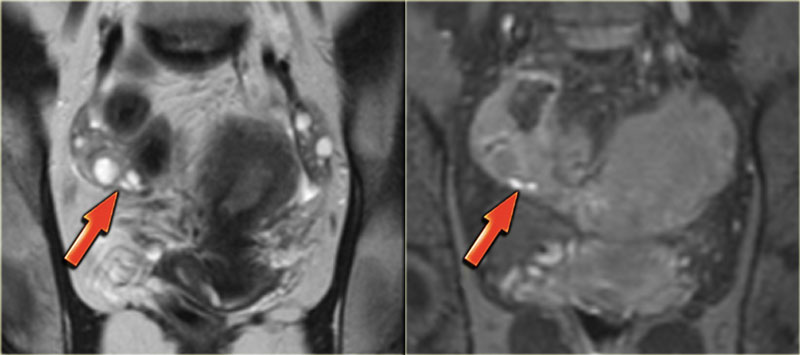

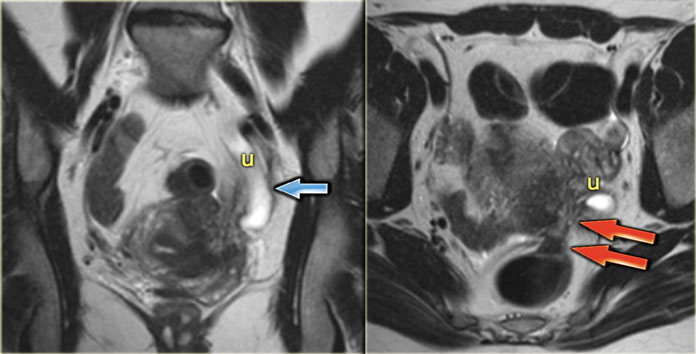

LEFT: Coronal T2WI: kissing ovaries due to adhesions RIGHT: Coronal T1WI+FS demonstrating small hemorrhages (red arrows)

LEFT: Coronal T2WI: kissing ovaries due to adhesions RIGHT: Coronal T1WI+FS demonstrating small hemorrhages (red arrows)

Adhesions

Endometriosis is frequently complicated by adhesion formation.

On MRI adhesions can be seen as spiculated, low- to intermediate

signal intensity strandings on T1 and T2.

Adhesions can fixate the pelvic organs, leading to posterior displacement of uterus and ovaries, elevation of the posterior vaginal fornix and angulation of bowel loops.

They may also lead to hydronephrosis, although in most cases hydronephrosis is caused by fibrosis secondary to the endometriosis.

The T2- and fatsat T1-images on the left show a patient with endometriosis in whom the ovaries are stuck together ('kissing ovaries'), as a result of extensive adhesion formation.

In this patient a small hemorrhagic cyst of the left ovary and a hemorrhagic superficial plaque are also shown (high signal on T1 red arrows).

These T2-images show dilatation of the left distal ureter caused by extensive deep infiltrating endometriosis involving the left sacrouterine ligament extending to the sigmoid colon.

Endometriomas

Endometriomas - also known as chocolate cysts - develop when superficial endometriotic lesions on the surface of the ovary invaginate.

Blood produced by such an implant during each menstrual cycle cannot escape and will accumulate within the ovary, forming a cyst known as an endometrioma.

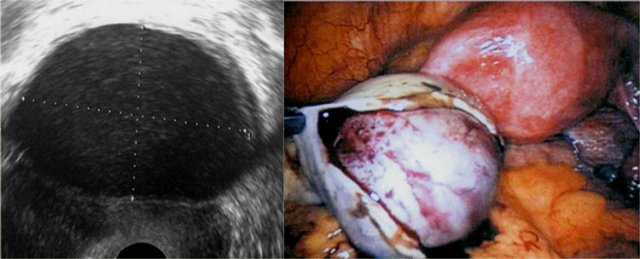

Endometriomas present as complex cystic masses, often thick-walled with a homogeneous content.

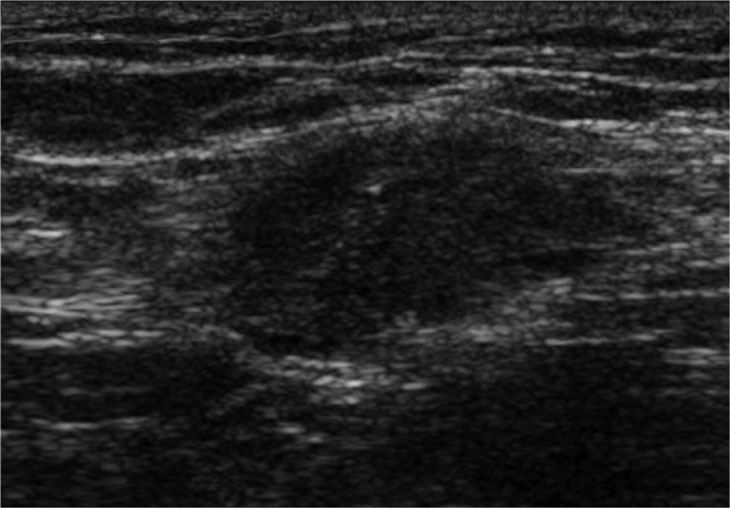

On transvaginal ultrasound, endometriomas may be seen as thick-walled

cysts with low level echoes.

On the left a transvaginal ultrasound image and the corresponding laparoscopic image during cystectomy.

T2- and fatsat T1-images of an endometrioma with hypointensity on T2 (shading), fluid-fluid levels on T2 (left) and hyperintense blood on T1WI with fatsat (right)..

T2- and fatsat T1-images of an endometrioma with hypointensity on T2 (shading), fluid-fluid levels on T2 (left) and hyperintense blood on T1WI with fatsat (right)..

On MRI, endometriomas present as solitary or multiple masses

with a homogeneous hyperintense signal intensity on T1- and T1-fatsat sequences.

The T1-fatsat helps differentiate endometriomas from mature cystic teratomas, which usually contain fat.

On T2WI, endometriomas may range from having a low signal intensity (also known as shading) to an intermediate or high signal intensity.

The low signal intensity reflects the hemoconcentration of a cyst.

Endometriomas generally have a thick, fibrous capsule with low signal intensity on T2, caused by hemosiderin-laden macrophages (figure).

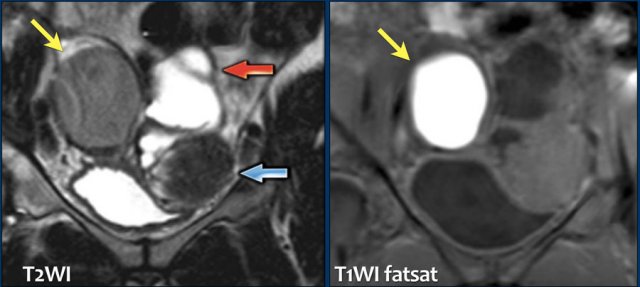

These images are of a patient with an endometrioma of the right ovary (yellow arrow).

It demonstrates intermediate signal on T2 and high signal intensity on T1-fatsat.

In addition there is:

- Hydrosalpinx with high signal on T2WI and low signal on T1-fatsat (red arrow).

- Leiomyoma with low signal intensity on T2WI and intermediate signal on T1-fatsat (blue arrow).

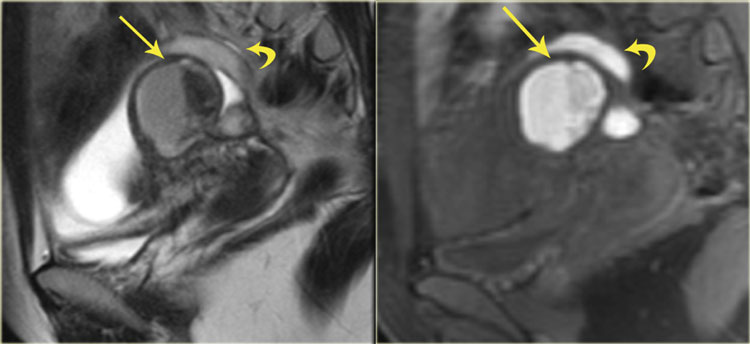

On the left another example of an endometrial cyst.

The T2- and fatsat T1-images show a cyst with a

bloodclot (hypointense on T2, intermediate on T1).

Sometimes these clots are accompanied by fibrotic tissue at histopathology.

They may be recognized as irregularly shaped, hypointense lesions (on T2) found in the dependent portion of the endometrial cysts.

In this case there is also a hematosalpinx (curved arrow).

The T2- and fatsat T1-images on the left show an endometrial cyst of the left ovary.

The wall of the cyst is hypointense on T2WI and T1WI caused by hemosiderin.

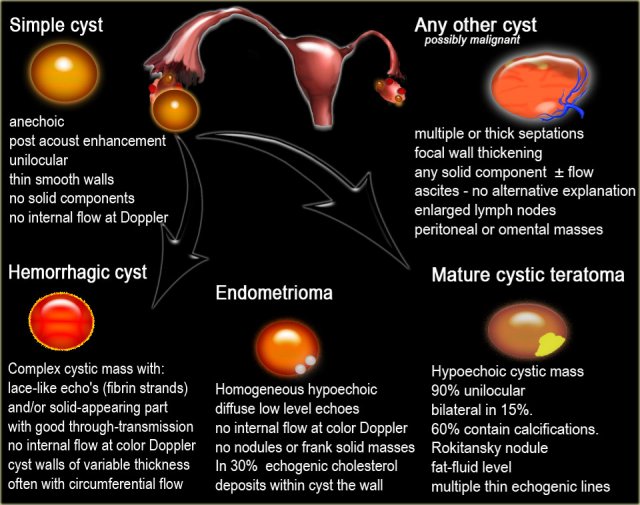

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of endometrial cysts includes: hemorrhagic

functional cysts, fibrothecoma, cystic mature teratoma, cystic ovarian neoplasm and ovarian abscess.

Click on the links below for more information about the differential diagnosis.

Abdominal wall endometriosis

Endometrial implants have been reported in many unusual sites outside the pelvis including the chest.

Abdominal wall endometriosis is the most common location of extrapelvic endometriosis and usually occurs after cesarean section.

Sonography shows a solid hypoechoic lesions in the abdominal wall , frequently containing internal vascularity on power Doppler examination.

These sonographic findings are nonspecific, and a wide spectrum of disorders should be considered in the differential diagnosis including neoplasms such as a sarcoma, desmoid tumor, or metastasis and nonneoplastic causes such as a suture granuloma, hernia, hematoma, or abscess.

However, abdominal wall endometriosis should always be your prime concern in patients with an abdominal wall mass nearby a cesarean section scar.

The CT and MR characteristics of abdominal wall endometriosis are nonspecific, both showing a solid enhancing mass in the abdominal wall.

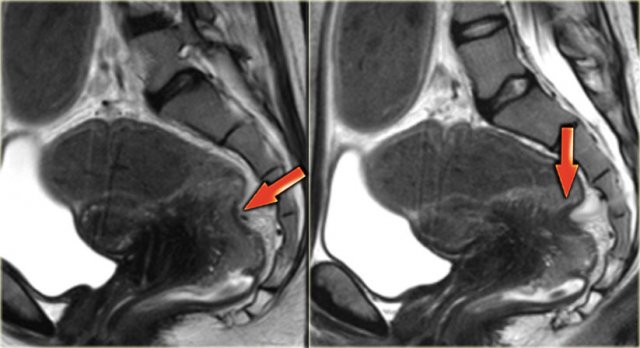

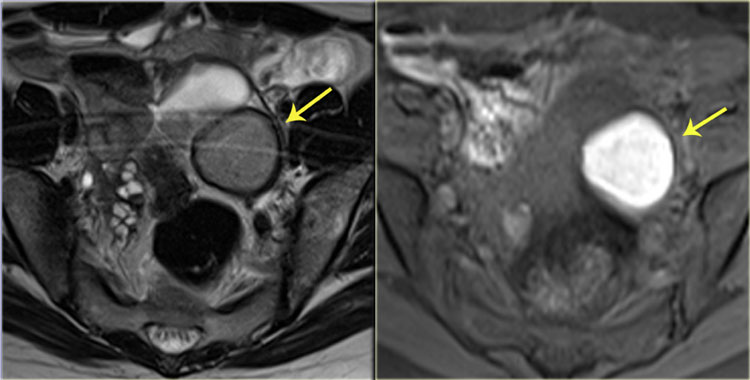

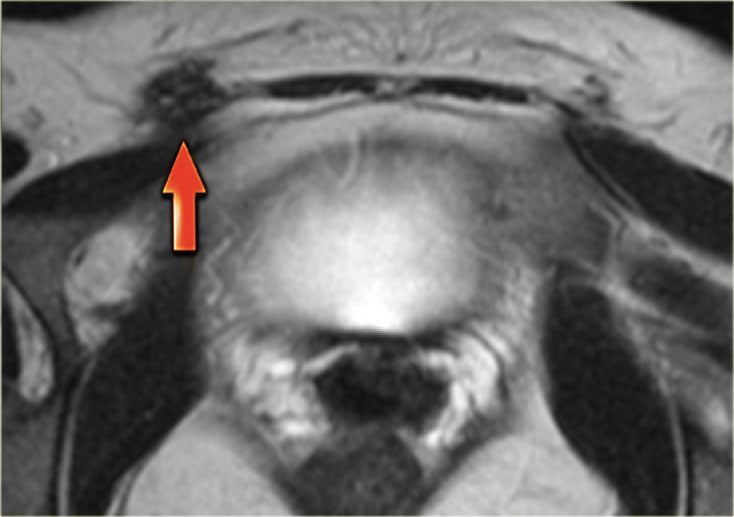

On the left MR-images of a patient with abdominal wall endometriosis.

On T2WI, the lesions have an isointense signal to muscle with small foci of

high signal intensity, indicating dilated endometrial glands.

They have a slightly higher signal intensity to muscle on the fatsat

T1-image (arrow).

A characteristic clinical symptom of abdominal wall endometriosis is cyclic pain associated with the menses, but patients may also present with continuous pain or no pain at all.

The axial T2-weighted image on the left demonstrates another case of abdominal wall endometriosis.