Pulmonary Fibrosis

A stepwise approach to fibrosis on HRCT

Onno Mets, Lilian Meijboom and Robin Smithuis

Radiology department of the Amsterdam University Medical Center and Alrijne hospital Leiderdorp

Publicationdate

In this article we will discuss lung diseases with a reticular pattern and provide a guidance for radiologists to evaluate the most common diseases and their patterns.

A stepwise approach is presented to identify the key features in fibrotic lung disease and to make it easier to reach a differential diagnosis.

Images can be enlarged by clicking on them.

We would like to thank Nestor L. Müller for his comments on the manuscript draft.

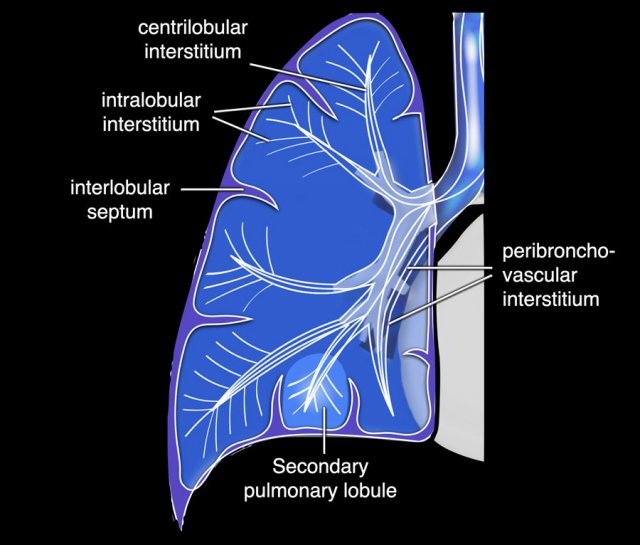

Lung anatomy

The anatomy of reticular lung disease is all about the pulmonary interstitium, which is a continuum that comprises both a peripheral and axial component (fig).

The peripheral interstitium supports the distal secondary lobules and involves the subpleural and perifissural areas, whereas the axial interstitium supports the bronchovascular structures from the hilum towards the periphery.

The interstitium also contains the lung lymphatics. Under normal circumstances the interstitium itself is below the resolution of CT.

Thickening of the interstitium is the underlying mechanism of a reticular pattern.

The Fleischner glossary of terms [1] defines reticulation as “a collection of innumerable small linear opacities that, by summation, produces an appearance resembling a net”.

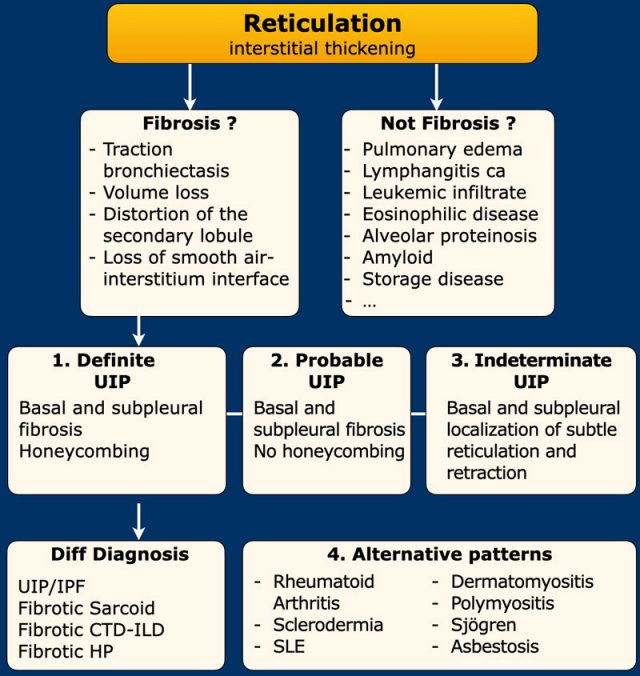

Stepwise Approach

The first step is to determine whether reticulation really represents fibrosis.

The next step is to determine if it is definite, probable or indeterminate UIP pattern, or an alternative pattern.

If it is definite or probable UIP, one needs to realize that not all UIP equals idiopathic lung fibrosis, as UIP with/without honeycombing can also be seen in fibrotic sarcoid, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and end stage connective tissue disease related-ILD (CTD-ILD).

Step 1 - Is it really fibrosis?

Fibrosis causes traction on surrounding structures and will lead to:

- Volume loss

- Bronchiectasis

- Distortion of the secondary lobule

- Loss of the smooth air-to-interstitium interfaces

Hence, these are the first features to look for when assessing whether the reticulation represents lung fibrosis or not.

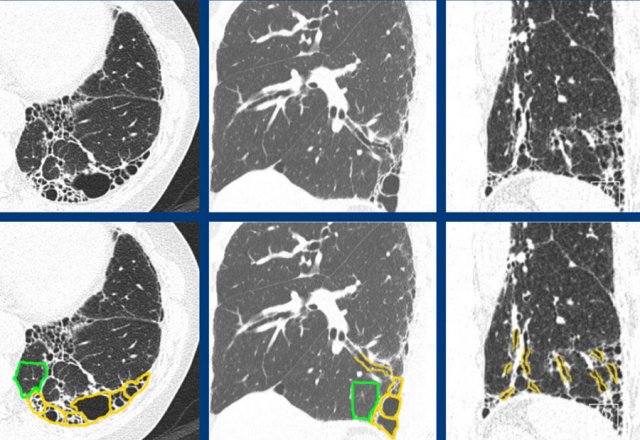

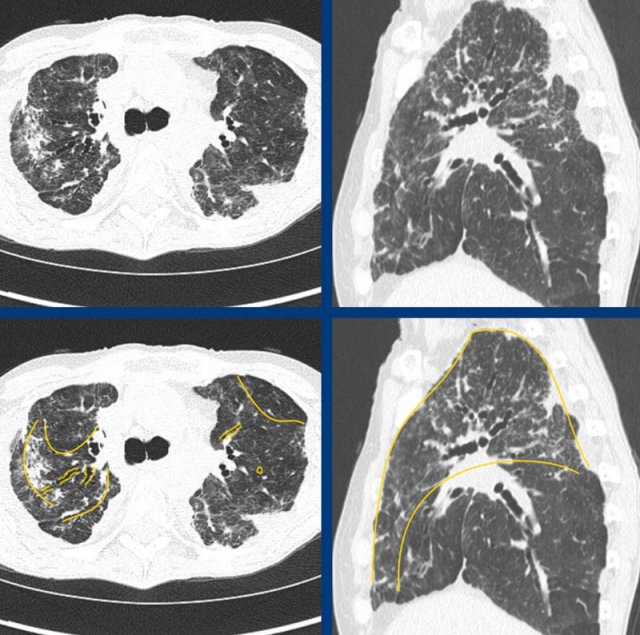

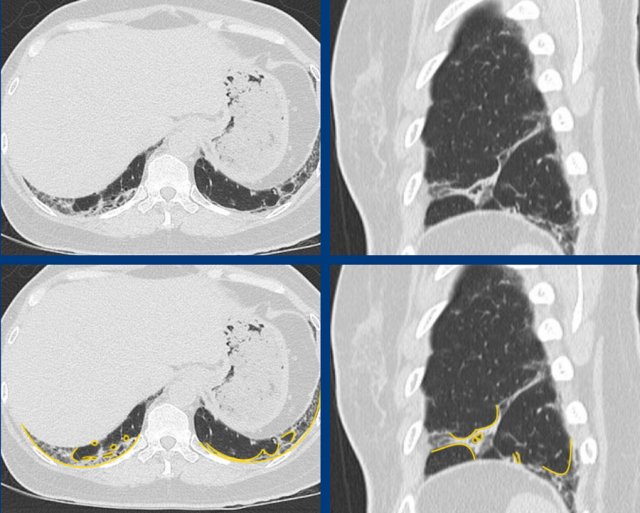

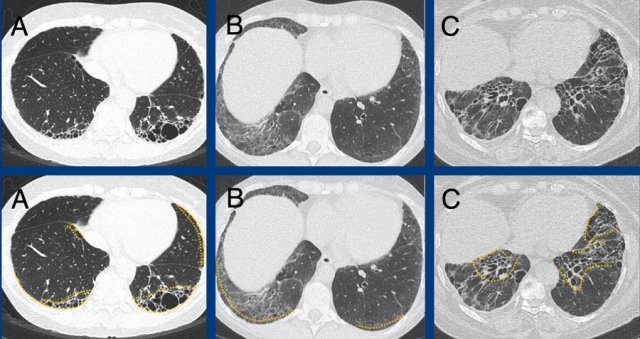

The images show fibrotic lung disease with distortion of the secondary lobule, volume loss and traction bronchiectasis (green is normal, yellow is abnormal).

Not all reticulation is fibrosis, as the pulmonary interstitium can be thickened by other pathology.

Most commonly this is:

- Fluid due to pulmonary edema.

But can also been seen in for example: - Malignant cells in lymphangitic carcinomatosis, or leukemic infiltration

- Proteins in alveolar proteinosis, amyloid and storage disease

- Benign cells in eosinophilic

lung disease

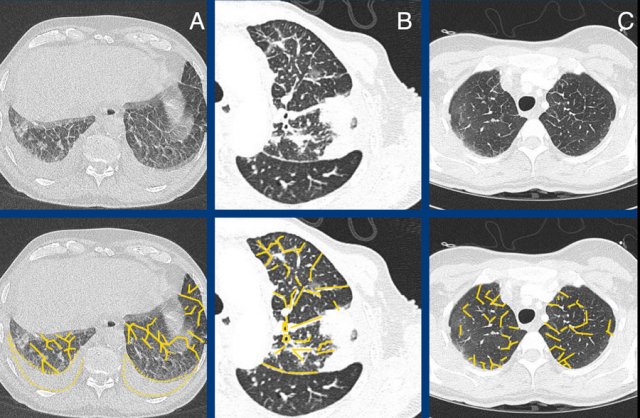

The images show examples of non-fibrotic reticulation due to interstitial thickening in pulmonary edema (A), lymphangitic carcinomatosis (B), and eosinophilic infiltration in eosinophilic granulomatis with polyangitis [EGPA, former Churg-Strauss syndrome] (C).

ILA -interstitial lung abnormalities

Incidental mild interstitial changes – in patients clinically not suspected of ILD – have been named ‘interstitial lung abnormalities (ILA)’.

These indeterminate and minor changes may represent an early stage of fibrotic interstitial lung disease, but may also just represent some post-infectious scarring or mild smoking- or age-related interstitial changes.

A cut-off of 5% lung involvement has been suggested as a discriminator for significant disease [2], however, accurate visual assessment is very difficult.

Follow-up may show whether or not it is a relevant incidental finding, which is optional and depending on patient characteristics.

Step 2 – UIP pattern

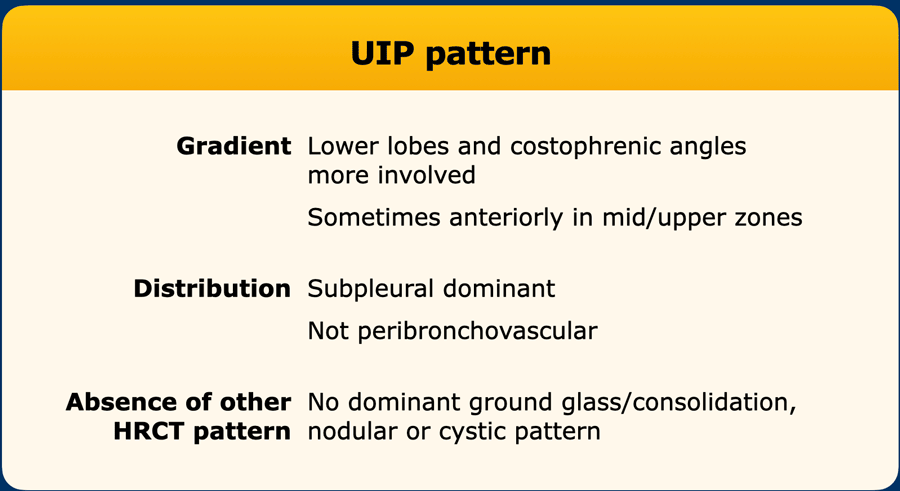

A UIP pattern is based on the disease gradient, distribution of the fibrosis and absence of another dominant HRCT pattern.

Another HRCT pattern like ground-glass, lung cysts, centrilobular or perilymphatic nodules and consolidation should be absent, since these are associated with other underlying disease and point away from a UIP/IPF diagnosis.

First the fibrosis has to show a gradient towards the lung bases, with the lower lobes and costophrenic angles more extensively involved than the mid and upper lung zones.

The fibrosis may be somewhat more anterior in the mid/upper lung zones, which has been named the ‘propeller sign’, after the twist that is present in a propeller blade.

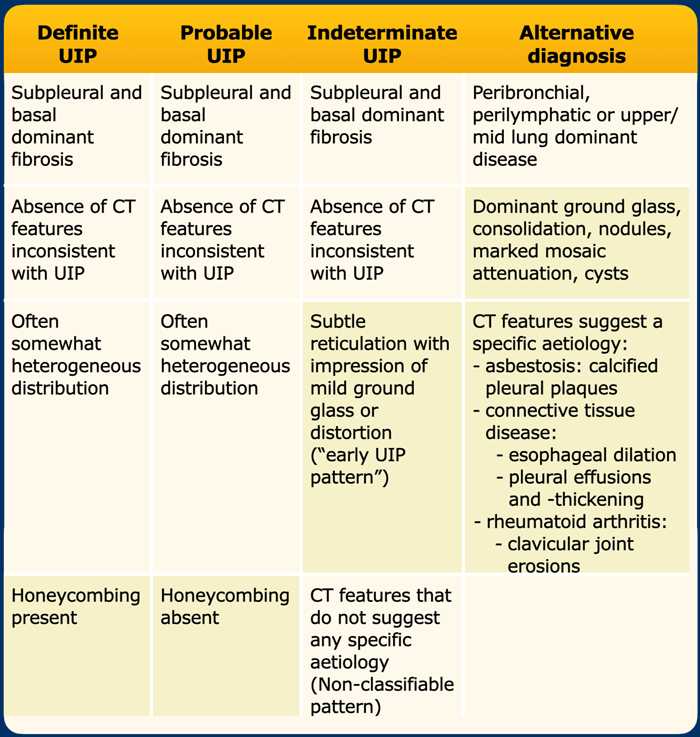

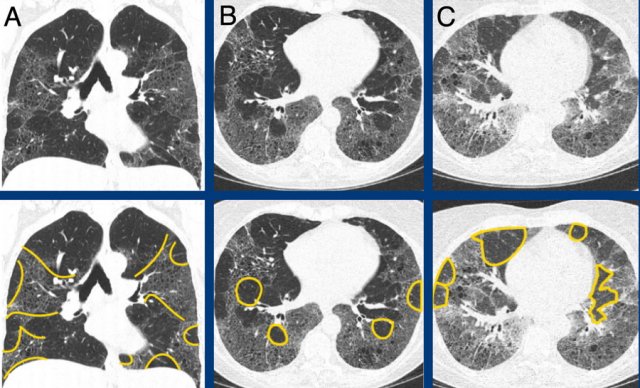

The images show a basal and subpleural dominant pattern in A versus an apical and central dominant fibrotic disease in B.

Subpleural dominant (A), subpleural sparing (B), and peribronchial dominant (C) patterns of fibrosis.

Subpleural dominant (A), subpleural sparing (B), and peribronchial dominant (C) patterns of fibrosis.

Second, the fibrosis has to be subpleural dominant. This means that the disease targets the peripheral interstitium and involves the lung directly beneath the pleura.

It should not spare the subpleural lung tissue, nor should it centre around the bronchovascular bundle (ie. predominantly involve the axial interstitium).

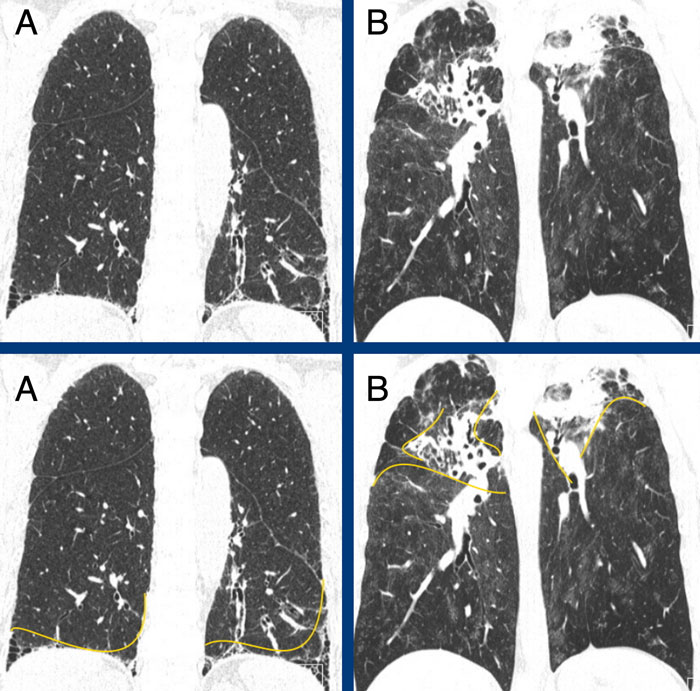

UIP classification

There are specific imaging guidelines for UIP/IPF evaluation - issued by both a collaboration of worldwide Thoracic Societies (ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT) as well as by the Fleischner Society [3,4].

The bottom line of both guidelines is that HRCT imaging should reach a conclusion of either:

- Definite UIP pattern

- Probable UIP pattern

- Indeterminate UIP pattern

- Suggestive of another diagnosis than UIP/IPF

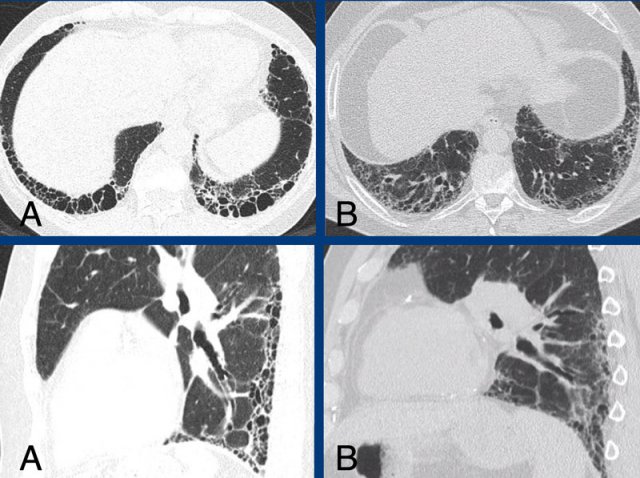

In a patient with basal and subpleural dominant fibrosis, without inconsistent ancillary features, the presence or absence of honeycombing determines whether to assign a definite or probable UIP pattern.

However, honeycombing assessment may suffer from substantial interobserver variability, even among experts [5].

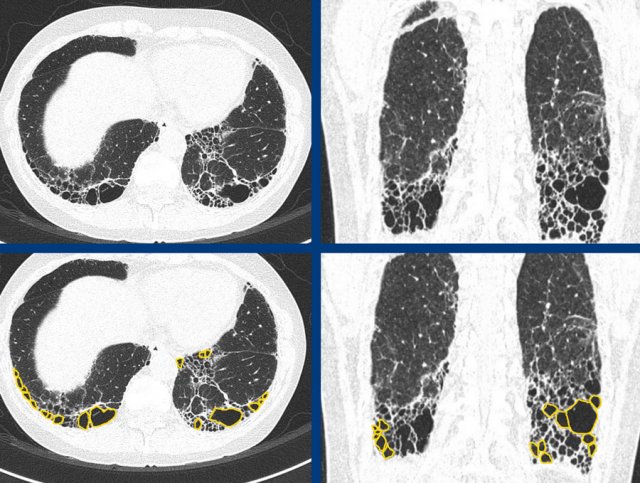

Honeycombing on CT imaging is defined as “subpleural oriented clustered cystic air spaces, typically on the order of 3-10 mm”.

Note is made that it is different from the honeycombing seen on histopathology, which is defined as “destroyed and fibrotic lung tissue containing numerous cystic airspaces with thick fibrous walls, with complete loss of acinar architecture” [1].

Although both represent established and severe fibrosis, they are seen at significantly different levels of magnification.

In A there is honeycombing combined with basal and subpleural dominant fibrosis indicating a definite UIP pattern.

In B there is a probable UIP pattern without honeycombing.

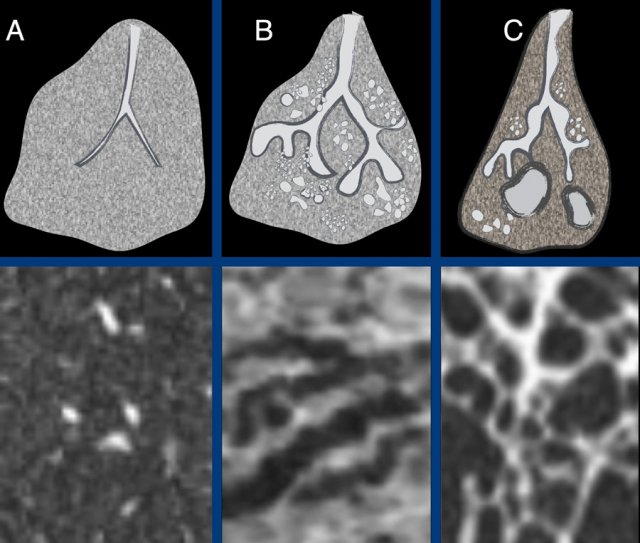

The ongoing process of honeycombing formation. There is a spectrum ranging from normal lung tissue (A), through distortion of the secondary lobule with traction bronchiolectasis (B), to end stage cyst formation (C).

The ongoing process of honeycombing formation. There is a spectrum ranging from normal lung tissue (A), through distortion of the secondary lobule with traction bronchiolectasis (B), to end stage cyst formation (C).

Honeycombing is the result of progressive fibrosis with architectural distortion and is at the end of the scale from normal lung tissue, through distortion of the secondary lobule with traction bronchiolectasis, to end stage cyst formation.

Although the presence of honeycombing defines the difference between a probable and definite UIP pattern, honeycombing is not pathognomonic for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) as it is just a feature of severe fibrosis.

Honeycombing may also be present in the fibrotic (end-)stages of sarcoidosis, NSIP and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. In short, a UIP pattern does not equal IPF.

But,

in the correct clinical setting ina patient clinically suspected of idiopathic

pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) a UIP pattern will seal the case (ie. diagnosis of

UIP/IPF), eliminating the need for further invasive diagnostics like cryo- or

surgical lung biopsy.

Step 3 - Alternative Patterns

- Axial and non-basal distribution

Axial and non-basal distribution

When the interstitial disease is not mainly subpleural but rather predominantly peribronchial, the two main considerations are fibrotic chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) and sarcoidosis.

Apical dominance is often seen in sarcoidosis, but only in a minority of cases of chronic HP.

Typical fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis showing diffuse non-basal dominant (A), peribronchial orientated ground-glass and mild fibrotic changes with mosaicism (A and B), and expiratory air trapping (C).

Typical fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis showing diffuse non-basal dominant (A), peribronchial orientated ground-glass and mild fibrotic changes with mosaicism (A and B), and expiratory air trapping (C).

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

Typical fibrotic chronic HP is characterized by peribronchial fibrosis with various degrees of ground-glass and marked mosaic attenuation due to sparing of secondary lobules.

Expiratory air trapping due to small airways obstruction is a hallmark finding.

Centrilobular ground-glass nodules may be present, but are more often and dominantly seen in the subacute (non-fibrotic) stages of the disease.

The

fibrosis may show a random or diffuse distribution, or a mid- or upper lung

predominance with relative sparing of the bases.

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is the great mimicker.

The fibrosis in sarcoidosis typically shows peribronchovascular and mid to upper lung zone predominance with architectural distortion and central traction bronchiectasis, a varying amount of reticulation and, occasionally, even honeycombing.

While sarcoidosis initially typically manifests with bilateral hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, in the late fibrotic stage of the disease the nodes are usually normal in size and calcified.

The images show typical fibrotic sarcoidosis with peribronchovascular and apical dominant disease, showing (confluent) nodularity, reticulation and mild ground-glass, as well as extensive traction bronchiectasis.

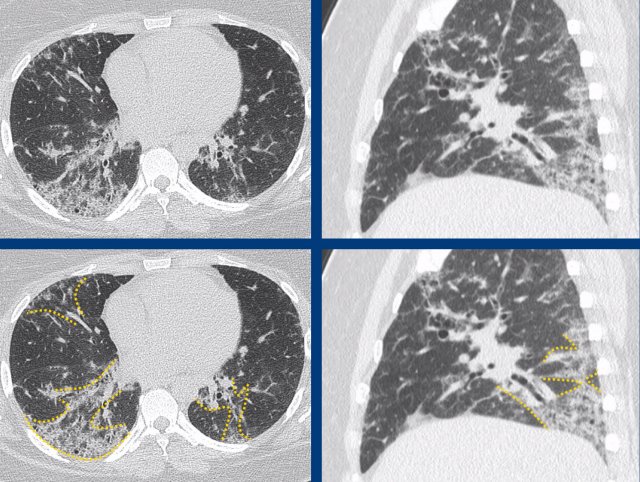

- Ground-glass pattern and Consolidation

Ground-glass

Although some ground-glass may be seen in areas of reticulation – a finding that does not exclude the diagnosis of probable UIP pattern - dominant ground glass component suggests an alternative diagnosis.

Ground-glass may point to a wide range of diseases, including connective tissue disease (CTD) related ILD, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, as well as smoking-related and drug-related ILD.

Ground-glass is often a feature of non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) pattern.

Pure ground-glass without fibrotic changes is the hallmark feature of cellular NSIP, separated from fibrotic NSIP pattern in which there is reticulation, traction bronchiectasis, and architectural distortion due to fibrosis.

NSIP is typically basal dominant with marked ground-glass, reticulation and traction bronchiolectasis. Subpleural sparing of the dorsal regions of the lower lobes is present in (only) approximately 40% of cases and may be a helpful feature in making the diagnosis.

Consolidations

Consolidations are not part of a probable UIP pattern. Small focal areas of fibrosis may be seen in UIP, however, more significant consolidation in HRCT imaging is often due to organizing pneumonia component and suggests a diagnosis other than UIP/IPF.

Active pulmonary infection or malignancy should always be considered.

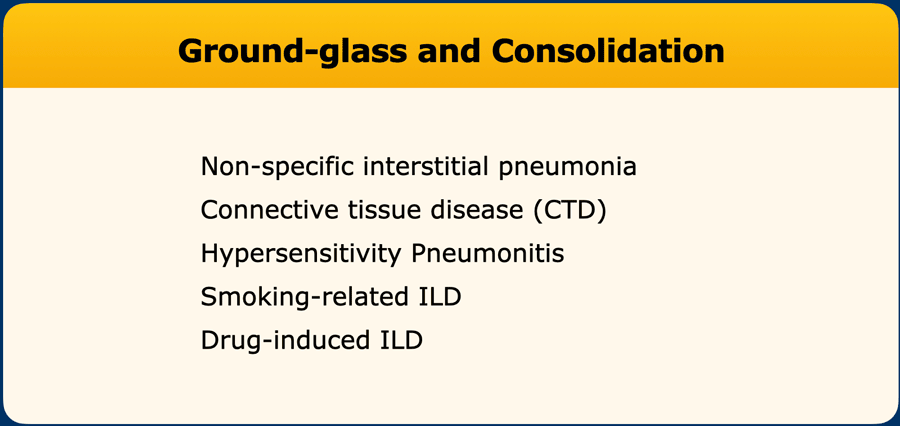

Connective tissue disease related ILD

The table shows the imaging patterns in connective tissue disease related interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD), where font size correlates to imaging pattern frequency.

CTD-ILD can result in many different patterns.

Within the overall heterogeneous group, disease manifestation with NSIP pattern as well as other components such as arcade-like consolidations due to OP (organizing pneumonia) or cysts due to LIP (lymphoid interstitial pneumonia) may hint toward a specific diagnosis (see Table).

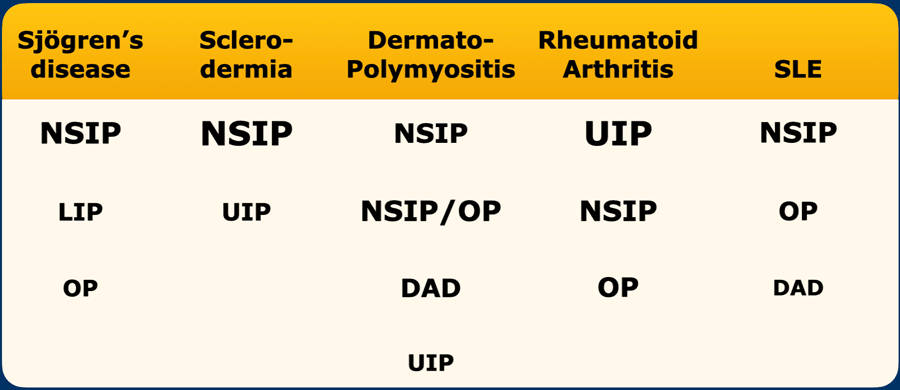

NSIP

Classic fibrotic NSIP pattern in Sjögren’s disease with fibrotic changes and dominant ground-glass in a basal dominant pattern that extends somewhat more centrally.

Subpleural sparing is not a dominant feature in this case.

The images show a combination of basal dominant groundglass and traction bronchiectasis, combined with limited perilobular arcade-like consolidations due to co-existing organizing pneumonia (OP).

The final diagnosis was fibrotic NSIP in anti-synthetase syndrome.

Anti-synthetase syndrome is an immune-mediated multisystem disorder that can include (among others) interstitial lung disease, myositis and/or polyarthritis, skin changes and Raynaud’s phenomenon.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Severe fibrotic changes in a subpleural and basal dominant orientation, with extensive honeycombing, consistent with a UIP pattern due to rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Rheumatoid arthritis can show multicompartment involvement and result in airways disease, pleural disease and interstitial lung disease, most commonly with a UIP pattern.

Smoking-related ILD

Smoking-related interstitial lung disease is a difficult subgroup which typically shows profound emphysema with milder superimposed fibrotic changes, more diffuse or apical dominant abnormalities, less severe basal volume loss and more ground-glass when compared to (probable) UIP pattern.

However, smoking-related changes of the lung often coincides with other interstitial lung disease as a substantial number of ILD patients are (former) smokers.

Smokers rarely suffer from chronic HP, while it is an individual risk factor for UIP/IPF.

Smoking-related interstitial fibrosis (SRIF) and combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE) are regularly used terms, however, as radiological patterns not strictly defined.

Drug-induced ILD

Drug-induced interstitial lung disease is a difficult subgroup with often non-specific imaging features.

It should always be considered in every differential diagnosis, especially in cases showing a non-UIP pattern.

Classically, drug-induced ILD is associated with dominant ground-glass and/or organizing pneumonia consolidation pattern, more than frank fibrosis.

Methotrexate, Amiodarone and Nitrofurantoin are well-known examples of pneumotoxic drugs, although a near endless list has been recognized.

Compared to the past decades, the increasing use of immunotherapy will likely lead us to encountering drug-induced pneumonitis patterns more often.

See www.pneumotox.com for more information on pneumotoxic drugs and their reported associated imaging patterns.

Radiologically non-classifiable disease

Not uncommonly HRCT findings do not conform to one of the well known radiological patterns.

This may be due to limited and nonspecific interstitial changes, or due to a combination of features that are truly indeterminate.

For example, there may be subpleural dominant reticulation and traction bronchiectasis, but without a clear gradient or questionable groundglass component and no other ancillary findings to suggest a specific diagnosis.

It is often felt to be an act of weakness to not conclude on an imaging pattern, however, it is stressed that “radiologically non-classifiable disease” is also a valid conclusion of the HRCT report.

In fact, it is much better than “possibly UIP, differential NSIP or HP”.

Multidisciplinary approach

Diagnosing a classic disease based on typical imaging findings is not that common.

Instead, it is more common to have a differential diagnosis as imaging features may be nonspecific.

In a multidisciplinary team imaging findings can be correlated to clinical information, pulmonary function test, lab results, bronchoalveolar lavage and lung biopsy findings to reach a consensus diagnosis and treatment plan.

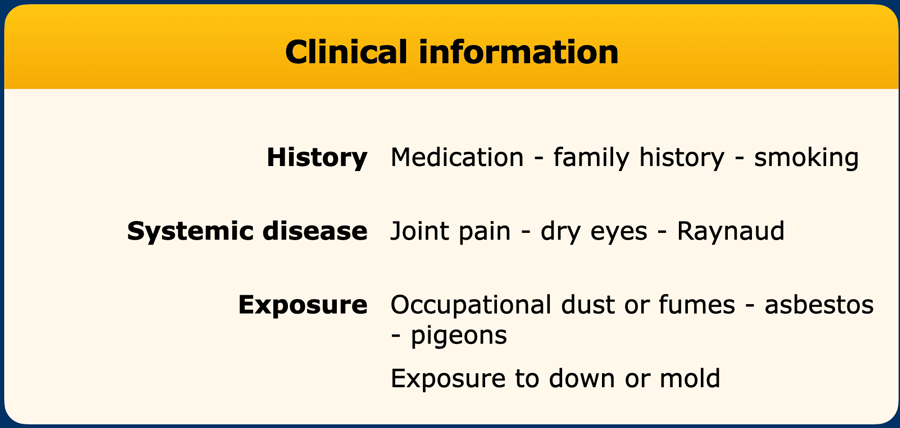

Clinical information

During the evaluation of an ILD patient clinical information is gathered (table)

Despite that for example over 200 agents have been associated with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, yield of occupational and environmental exposure analysis is unfortunately often limited.

Pulmonary Function Tests

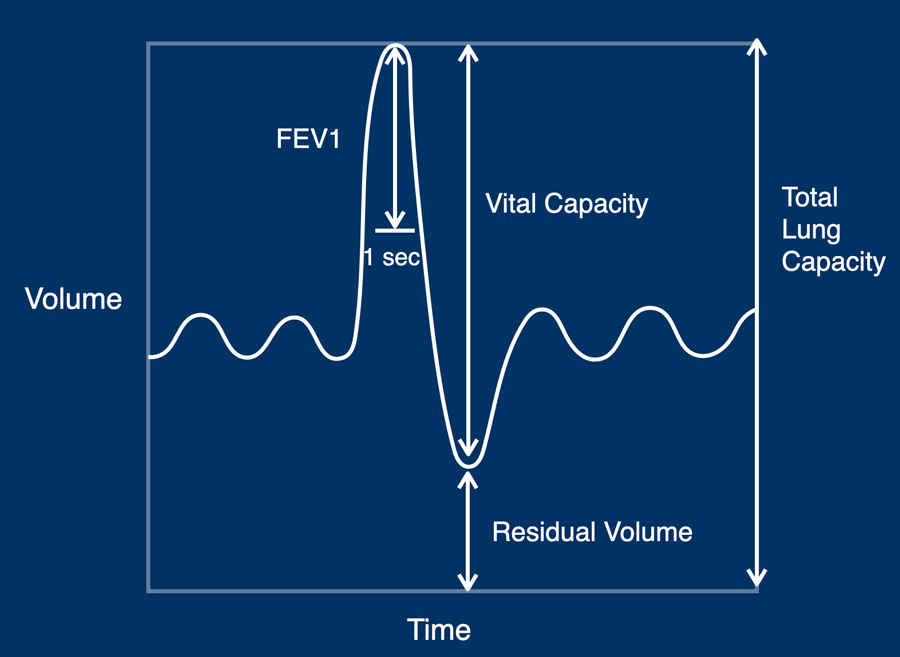

A basic understanding of pulmonary function test mechanics is helpful.

There are three major components in lung function testing:

- Static lung volumes (TLC, RV, VC)

- Spirometry (forced expiratory flow in 1 second’ (FEV1)

- Diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO)

Index parameters in static lung volume assessment are:

- TLC: total lung capacity, which is the total volume of the lungs after maximum inspiration

- RV: residual volume, which is the lung volume at the end of maximum expiration

- VC: vital capacity, which is the difference between TLC and RV

Typically, lung volumes are decreased in restrictive lung disease (eg. lung fibrosis, neuromuscular disease) and increased in obstructive lung disease (eg. COPD, asthma).

DLCO measures the capacity for carbon monoxide gas exchange, and is a surrogate marker for the ability of oxygen to be delivered to the blood.

DLCO is directly proportional to the alveolar-capillary membrane surface area and inversely proportional to alveolar-capillary membrane thickness.

Typically, DLCO is decreased in diseases that either lower the membrane surface area (eg. emphysema, thromboembolic disease) or thicken the membrane over which diffusion takes place (eg. lung fibrosis).

The classic PFT pattern in lung fibrosis is restrictive, showing relatively normal spirometry with decreased lung volumes and DLCO.

However, a mixed pattern can be seen if patients who have both restrictive and obstructive disease components.

For example, advanced stages of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis or sarcoidosis may show both small airway disease and lung fibrosis simultaneously.

Also, summative contributions of emphysema and fibrosis in ‘combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema’ (CPFE) may lead to ‘pseudo-normalisation’ of spirometry and lung volumes, while clinical symptoms and DLCO are usually profoundly abnormal.

Laboratory analysis

The search for inflammatory markers and auto-antibodies are part of standard ILD evaluation.

It is important to realize that the presence of an auto-antibody does not equal a diagnosis of an autoimmune disease.

Rather, a positive serology helps to support a diagnosis if accompanied by appropriate clinical signs and symptoms.

Common biomarkers are:

- Rheumatoid factor (RF)

may point towards rheumatoid arthritis (RA), but has limited sensitivity and specificity. It may be seen in other diseases including for example M. Sjögren, SLE and various infectious diseases. - Anti-CCP

has a high specificity but limited sensitivity for RA. It can also be present in for example psoriatic arthritis, SLE, M. Sjögren and inflammatory myopathies. - Myositis specific antibodies

mostly referred to as ‘myositis blot’, because of the high specificity to the autoimmune inflammatory myopathies (IIM) such as dermatomyositis. - Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)

come as either cytoplasmic (cANCA) or perinuclear (pANCA), and are hallmark biomarkers for vasculitis. - Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and interleukin-2 receptor (sIL2R)

are biomarkers used in the evaluation and follow-up of sarcoidosis. - Serum precipitins

are serum IgG antibodies against specific antigents (eg. parrot or goose) and are used in the evaluation of hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)

Immunologic BAL is a diagnostic procedure to retrieve respiratory secretions.

There is limited value of BAL results in UIP/IPF diagnosis, other than exclusion of other underlying aetiologies.

- Lymphocytosis in the BAL fluid (ie. cell count >25%) is quite likely to be caused by ILD associated with granuloma formation (eg. hypersensitivity pneumonitis or drug toxicity), especially if accompanied by plasma cells and an appropriate exposure history.

- High eosinophil cell count points towards underlying eosinophilic lung disease.

- Pigmented alveolar macrophages are often found in smokers, and may support a diagnosis of respiratory bronchiolitis (RB-ILD) or desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP).

- Diffuse alveolar haemorrhage (DAH) will produce reddish aspirate with positive hemosiderin stains.

Pathology

If there is still no diagnosis after clinical evaluation, CT imaging and additional diagnostic tests, the MDT may decide that a lung biopsy is needed.

This is however highly dependent on the patient’s wishes, co-morbidities and the available treatment options, as the procedure carries a relative high risk of complications and mortality.

Most often a video-assisted thoracoscopic (VATS) surgical lung biopsy is performed, in which typically three samples are taken from each lobe of the right lung.

A more recent option is an endoscopic cryobiopsy, however, yield is often suboptimal compared to surgical biopsies.

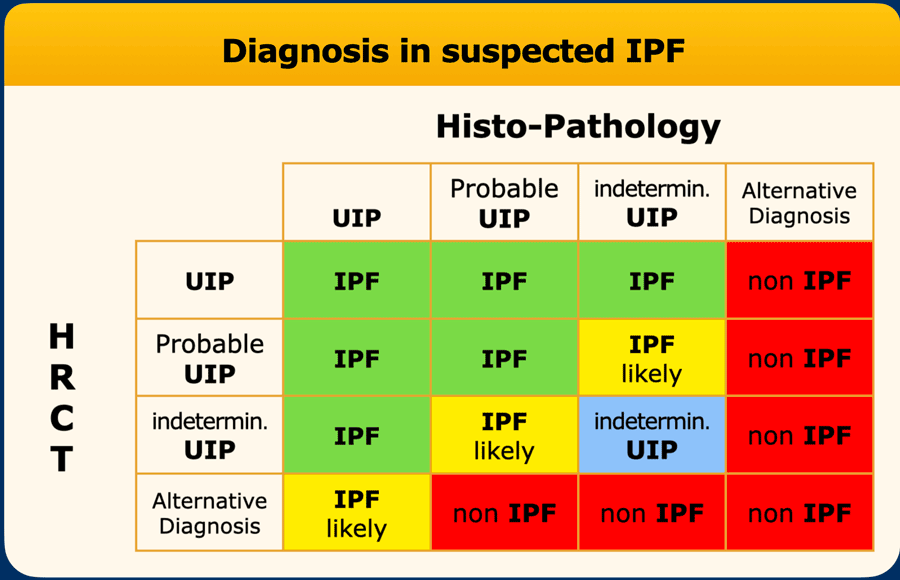

The final diagnosis of IPF is based on the findings on HRCT in combination with the histopathology (table).

Treatment and follow-up

ILD patients are most often followed with PFT and HRCT imaging to assess for disease progression.

Depending on the final diagnosis, medical therapy may be available.

A dichotomous split of therapeutic options is anti-fibrotic medication (in primarily fibrotic lung disease such as IPF) vs. immunosuppressive therapy (in immune-mediated fibrotic lung disease such as chronic HP or CTD-related ILD).

Medication may be combined with termination of exposure to antigens or pneumotoxic drug, smoking cessation, pulmonary rehabilitation, etc.

A lung transplantation may be the ultimate endeavour, if available.