Acute Aortic Syndrome

Aortic Dissection, Intramural Hematoma and Penetrating Ulcer

Ferco Berger, Robin Smithuis, Otto van Delden

From the Radiology Department of the Academical Medical Centre, Amsterdam and the Rijnland Hospital, Leiderdorp, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

The term Acute Aortic Syndrome (AAS) is used to describe three closely related emergency entities of the thoracic aorta: classic Aortic Dissection (AD), Intramural Hematoma (IMH) and Penetrating Atherosclerotic Ulcer (PAU).

Clinically these conditions are indistinguishable.

CT is the most accurate imaging modality for the initial diagnosis, differentiation and staging.

This review will discuss the imaging features and important pitfalls.

by Ferco Berger, Otto van Delden and Robin Smithuis

Radiology department of the Academical Medical Centre, Amsterdam and the Rijnland Hospital, Leiderdorp, the Netherlands.

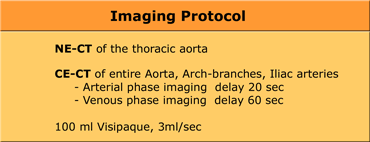

Imaging Protocol

Image protocol will be based on the type of scanner that is available.

Our imaging protocol is based on a 4 slice helical CT-scanner.

For the evaluation of patients with suspected AAS, we use 4x2,5 mm collimation technique

with 5 mm axial reconstructions and coronal, sagittal and oblique MPRs.

A non-enhanced scan of the thoracic aorta is included for the detection of an intramural hematoma (IMH).

This is followed by a contrast-enhanced scan of the aorta in the arterial phase with bolus triggering and in the venous phase (100 ml Visipaque, 3ml/sec).

Contrast differences between arterial and venous phase can be helpful in differentiating true and false lumen.

The iliac tract is included for evaluation of endovascular treatment possibilities.

The branches of the arch are visualized to evaluate the extend of dissection and awareness of possible neurological complications.

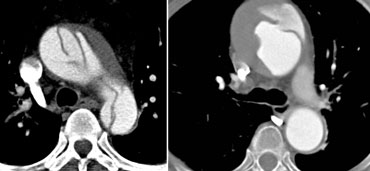

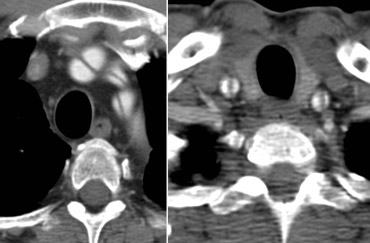

Type A dissection extending into the brachiocephalic arteries.LEFT: not visible on left arm injection.RIGHT: Same patient with right arm injection.

Type A dissection extending into the brachiocephalic arteries.LEFT: not visible on left arm injection.RIGHT: Same patient with right arm injection.

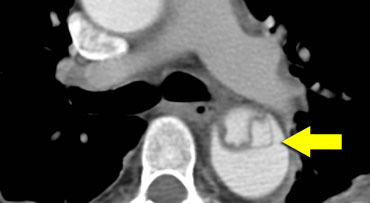

Important reduction of artifacts and thus decreasing pitfalls, can be achieved by:

- Contrast injection in RIGHT arm: no contrast crossing in front of arch side branches which distorts visibility of intima flaps (figure)

- saline bolus chaser (only contrast in lumina of interest)

- EKG-triggered imaging (less motion artifacts mimicking intima flap) Also keep in mind that placing ROIs can be difficult with dissected lumina (should be just distal to the aortic arch).)

Have the technician be prepared to manually start upon visual feedback.

Classification of Acute Aortic Syndrome

Classic Aortic Dissection (AD), Intramural Hematoma (IMH) and Penetrating Atherosclerotic Ulcer (PAU) are distinct entities, but closely related.

This is reflected upon in their identical therapeutical strategies.

The main goal for the radiologist is not only to detect which entity is causing the clinical problem, but more importantly to differentiate between type A and B!

Stanford classification

The Acute Aortic Syndrome (AAS) is classified according to Stanford.

Stanford Type A lesions involve the ascending aorta and aortic arch and may or may not involve the descending aorta.

Stanford Type B lesions involve the thoracic aorta distal to the left subclavian artery.

The Stanford classification has replaced the DeBakey classification (type I= ascending, arch and descending aorta: type II= only ascending aorta: type III= only descending aorta).

Treatment options for the 2 subgroups of the acute aortic syndrome (AAS) are very different:

- Stanford type A will be treated with surgery or endovascular therapy.

- Stanford Type B will be treated medically.

Aortic Dissection (AD)

Classic Aortic Dissection is the most common entity causing an acute aortic syndrome (70%).

- Incidence: 1-10 : 100.000

- mostly men

- rarely

- hypertension > 70%

- Type A mortality 1-2% per hour after onset of symptoms, total up to 90% non-treated, 40% when treated.

- 1 year survival Type B up to 85% if medically treated (5 year > 70%)

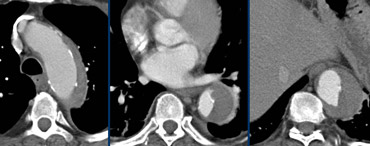

LEFT: Type A dissection with clear intimaflap seen within the aortic arch.RIGHT: Type B dissection. Entry point distal to left subclavian artery.

LEFT: Type A dissection with clear intimaflap seen within the aortic arch.RIGHT: Type B dissection. Entry point distal to left subclavian artery.

Management decisions are based on the following information:

- Type A or Type B

- Place of entry & re-entry

- Side branches involved, originating form true / false lumen

- Organs at risk (1/3 of mortality is caused by organ failure)

- Complications (rupture, coronairy occlusion, aortic insufficiency, neurological )

- Diameters of true and false lumina at: proximal and distal landing zones, at entry and at minimum

- Iliac vessel tortuosity

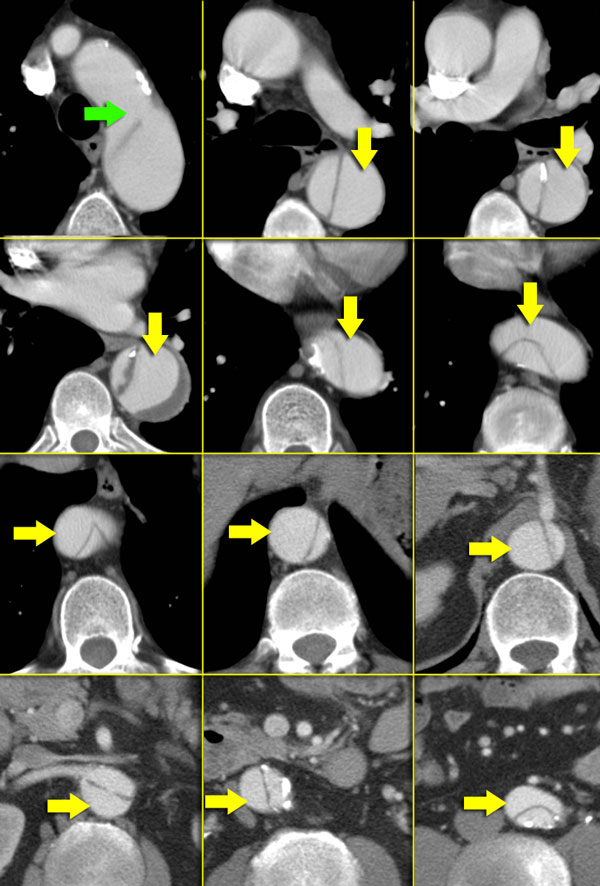

Type B dissection. Green arrow indicates entry. False lumen is indicated by yellow arrows and is seen spiraling around the true lumen.

Type B dissection. Green arrow indicates entry. False lumen is indicated by yellow arrows and is seen spiraling around the true lumen.

Imaging features

In Aortic dissection an intima flap is seen in only 70% of cases.

When there are 2 lumina, these will spiral around each other (figure).

On the left consecutive images are seen of a Type B dissection.

The true lumen is surrounded by calcifications.

The true lumen is smaller, as the false lumen wedges around the true lumen due to permanent systolic pressure (so called Beak-sign).

Thrombus material invariably is located in the false lumen, which enhances later than the true lumen.

True lumen:

- Surrounded by calcifications (if present)

- Smaller than false lumen

- Usually origin of celiac trunk, SMA and right renal artery

False lumen:

- Flow or occluded by thrombus (chronic).

- Delayed enhancement

- Wedges around true lumen (beak-sign)

- Collageneous media-remnants (cobwebs)

- Larger than true lumen

- Circular configuration (persistent systolic pressure)

- Outer curve of the arch

- Usually origin of left renal artery

- Surrounds true lumen in Type A dissection

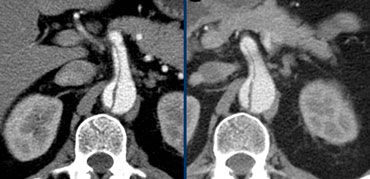

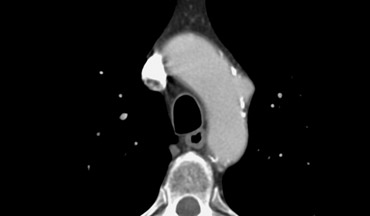

On the left an aortic dissection is seen with a large false lumen.

The compressed true lumen is seen on the inner side and is brighter than the false lumen.

Thrombus formation within the false lumen.

The true lumen usually is smaller as the false lumen wedges around the true lumen due to permanent systolic pressure.

The false lumen usually adheres to the outer curvature of the aortic arch, as is seen in this case.

Collageneous media-remnants (cobwebs) are only seen in the false lumen.

The same holds true for thrombusmaterial.

If one of the lumina is surrounded by the other, it invariably is the true lumen.

This almost only occurs in type A dissections.

The figures on the left both show a type A dissection with clear entry points in the ascending aorta.

The true lumen is surrounded by the false lumen, which is bigger and wedges around the true lumen due to permanent systolic pressure.

Dissection into brachiocephalic arteries

Carefully sort out which branches of the aortic arch are involved.

Make sure from which lumina they arise.

Left: Continued dissection into the celic trunk showing bigger false lumen, significantly contributing to organ perfusion.Right: : SMA and renal artery involvement, illustrating possible cause of organ malperfusion

Left: Continued dissection into the celic trunk showing bigger false lumen, significantly contributing to organ perfusion.Right: : SMA and renal artery involvement, illustrating possible cause of organ malperfusion

Dissection into abdominal arteries

The celiac trunc, SMA and right renal artery flow usually originates from the true lumen.

Left renal artery flow mostly originates from the false lumen.

Impaired perfusion of end-organs can be due to 2 mechanisms:

1) static = continuing dissection in the feeding artery (usually treated by stenting)

2) dynamic = dissection flap hanging in front of ostium like a curtain (usually treated with fenestration).

This may be hard to discern, MPR's can be helpfull.

Look for the re-entry point, usually to be found in the iliac tract.

Provide information about tortuisity and calcifications of the iliac tract if endovascular procedures are being considered.

When no end-organs are compromised and there is sufficient perfusion, dissection can be left alone.

This may persist for a long time without clinical consequence, as is seen in the patient on the left with follow-up of 2 years.

Some dissections remained unchanged during a follow up of more than 5 years.

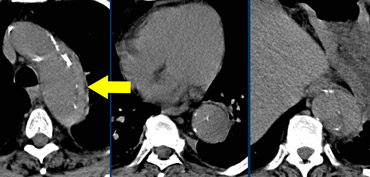

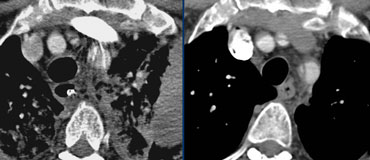

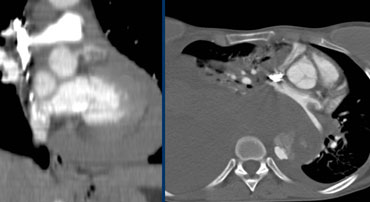

Left: pericardial fluid / hematoma indicates rupture of the dissected aorta. Even small amounts are proving rupture, though hematoma can be extensive such as in this case.Right: Massive hematoma caused by rupture of the dissected aorta into the mediastinum and pleural cavity, no pericaldial hematoma.

Left: pericardial fluid / hematoma indicates rupture of the dissected aorta. Even small amounts are proving rupture, though hematoma can be extensive such as in this case.Right: Massive hematoma caused by rupture of the dissected aorta into the mediastinum and pleural cavity, no pericaldial hematoma.

Rupture into pericardium and thoracic cavity

Even the slightest amount of fluid in pericardium, mediastinum or pleural cavity is suggestive of rupture of the dissection.

The cases on the left show evident rupture, with presence of extensive hematoma in above mentioned locations.

Note extreme hematothorax and hematomediastinum, causing shift of the mediastinum and compression on the pulmonary veins and even aorta.

No pericardial effusion visible.

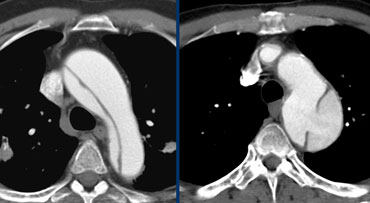

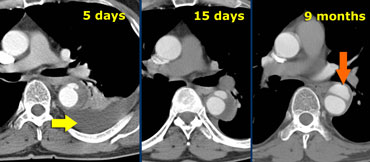

Type B aortic dissection in a non-operable patient. At 5 days flow reappeared in false lumen. Finally at 9 months a saccular aneurysm has formed.

Type B aortic dissection in a non-operable patient. At 5 days flow reappeared in false lumen. Finally at 9 months a saccular aneurysm has formed.

The case on the left is a patient who presented with a fully thrombosed false lumen.

5 days after initial presentation this patient complained of acute chest pain mimicking the earlier episode.

Re-examination showed recurrence of flow in the false lumen, locally contained, but with alarming adhering pleural effusion.

The patient could not undergo surgical or endovascular repair for various reasons and was treated consevatively.

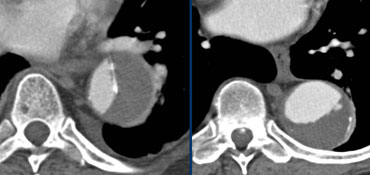

LEFT: Dissection with a thrombosed false lumen. RIGHT: Aneurysm with thrombus on the inner side of the intimal calcifications.

LEFT: Dissection with a thrombosed false lumen. RIGHT: Aneurysm with thrombus on the inner side of the intimal calcifications.

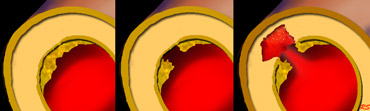

Aneurysm with thrombus versus thrombosed dissection

It can be difficult to differentiate an aneurysm with thrombus from a dissection with a thrombosed false lumen.

If there are intima calcifications this will be very helpfull.

A false lumen displaces the intimal calcifications.

Intramural Hematoma

Brief facts:

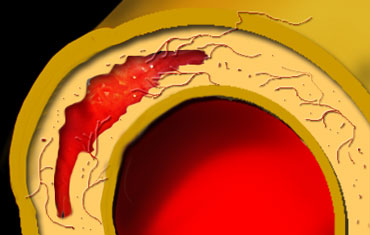

- Spontaneous hemorrhage caused by rupture of vasa vasorum in media

- 13% of dissections, usually no pulse deficit

- Difficult to distinguish from thrombosed AD

- Can proceed to classic dissection (16-47%)

- Long time to diagnosis: usually overlooked due to lack of non-enhanced scan

- Mortality at 1 year after dismission ~ 25%

What the clinician needs to know

- Type A or Type B

- Regression of aortic ? to normal in 80% of patients

- Predictors of mortality:

- Ascending Aorta > 5 cm ?

- IMH thickness > 2 cm

- Pericardial effusion (to less extend pleural effusion) - IMH may persist or evolve into aneurysm or PAU

- Associated PAU - worse prognostic outcome

On the left a Intramural hematoma, hyperdense on a NECT.

Same case contrast enhanced CT.

Note that the IMH does not spiral around the true lumen, like in classic AD, helping to differentiate both.

Essentially, this is not important, therapeutical decision will be made by whether this IMH is classified as Type A or Type B IMH!

Note that there is no pericardial effusion.

IMH thickness stays below 2 cm, making regression of this Type B IMH likely (up to 80%).

Penetrating Atherosclerotic Ulcer

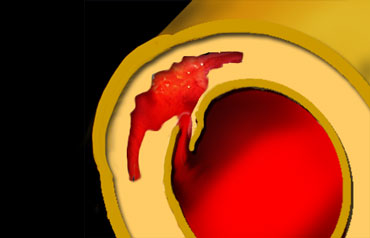

PAU is defined as an ulceration of an atheromatous plaque that has eroded the inner elastic layer of the aortic wall.

It has reached the media and produced a hematoma within the media.

Brief facts:

- Patients with severe systemic atherosclerosis

- Rarely rupture, yet worse prognosis due to extensive atherosclerosis which causes organfailure (e.g. acute myocardial infarction)

- Cause of most saccular aneurysms

- Located in arch and descending aorta

- Often multiple (therefore surgical treatment difficult, mostly treated medically)

Typical illustration of PAU, focal outpouchings of contrast, separating extensive intimal calcifications

Typical illustration of PAU, focal outpouchings of contrast, separating extensive intimal calcifications

What the clinician needs to know

- Type A or Type B

- Single or multiple

- Associated IMH (if not present, be cautious to mention PAU, clinical symptoms might not be caused by PAU, which is probably stable)

- Possibility of endovascular treatment

Imaging features

- Extensive atherosclerosis with severe intima calcifications and atherosclerotic plaques

- Focally displaced and separated intimacalcifications

- Crater and/or contrast extravasation

- -Focal IMH, longitudinal spread limited by mediafibrosis

- Possibly enhancing aortic wall

Complications

The complications of a Penetrating Atherosclerotic Ulcer include:

- Saccular aneurysm formation

- Compression of nearby structures

- Rupture

However most patients have a poor prognosis because of generalized atherosclerosis leading to diffuse organ failure.