Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Josephine Bomer-Skogstad¹, Kristian Thomassen² and Robin Smithuis³

Departments of Diagnostic Imaging of Akershus Universitets Sykehus in Lørenskog, Norway, Rikshospitalet in Oslo, Norway and Alrijne Hospital in Leiden, the Netherlands

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a severe inflammatory process of the neonatal bowel, ultimately resulting in bowel necrosis.

Clinical signs may be non-specific and imaging plays a key role in the diagnosis of NEC.

Ultrasound is the most sensitive modality for evaluating NEC.

in this article we will discuss:

- Imaging findings in NEC

- Main differential diagnosis

Introduction

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is mainly a disease of prematures (> 90% of cases).

It can also occur in term babies and in those cases NEC is usually associated with other diseases, such as sepsis or congenital heart disease.

NEC has a high mortality of up to 20-30% and may result in long term morbidity.

Image

Peroperative picture of a baby with necrotizing enterocolitis.

The difference between the necrotic bowel and the healthy well perfused bowel is easily noted.

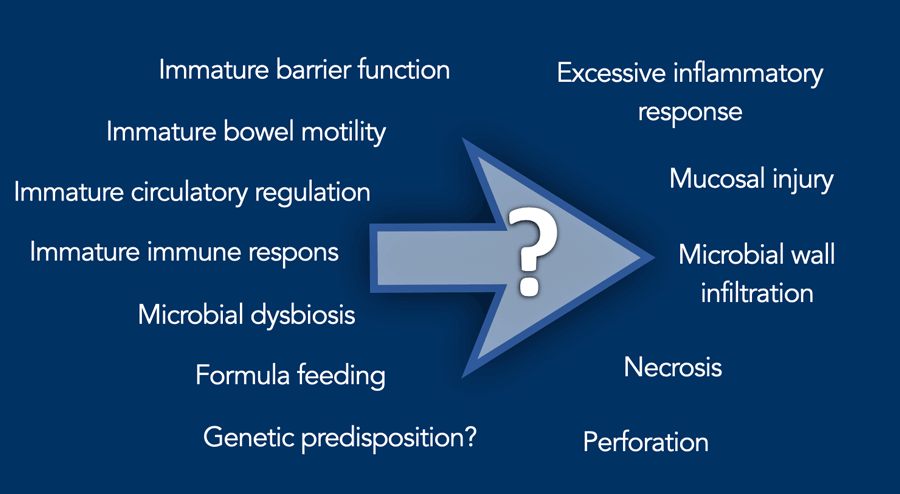

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of NEC is not entirely understood and there are many factors that play a role.

Hallmark is an immature bowel, which has an underdeveloped barrier function, allowing bacteria and toxins to penetrate and cause damage.

NEC is often associated with abnormal colonization of the gut.

The immature immune system may respond inadequately to pathogenic bacteria, potentially leading to an overwhelming inflammatory response.

Conditions that reduce blood flow to the intestines can trigger or exacerbate NEC.

Eventually necrosis and perforation may follow.

Breast milk is protective against NEC.

Formula feeding is linked to a higher risk due to the lack of protective components found in breast milk, such as growth factors, immune cells and antibodies.

Sometimes discoloration of the skin of the abdomen may be seen in NEC. Photograph courtesy of Dr M Vlietman.

Sometimes discoloration of the skin of the abdomen may be seen in NEC. Photograph courtesy of Dr M Vlietman.

The risk of developing NEC is inversely related to gestational age and birth weight.

In children born < 32 weeks gestational age or with a birth weight less than 1.5 kg, the risk of developing NEC is about 4-12%.

In term newborns NEC is very rare and you should first think of other diagnosis as listed in the differential diagnosis (see below).

The first signs of NEC typically occur in day 10-20 after birth.

It starts with non-specific signs such as lethargy, apnea or temperature instability.

Then more indicative of NEC are gastrointestinal signs such as feeding intolerance, gastric retentions, abdominal distention and bloody stools.

The work-up includes laboratory testing, including cultures to rule out sepsis, and imaging.

Imaging in NEC

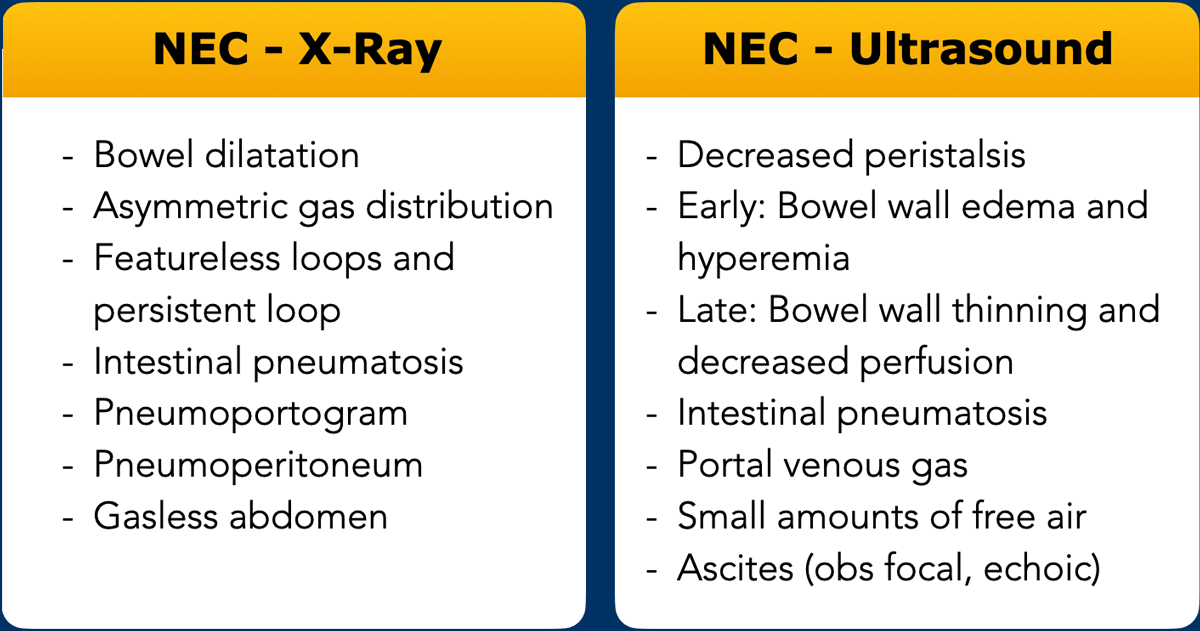

The table lists the findings you should look for on the abdominal X-ray and ultrasound.

These findings are discussed in detail below.

Tips in NEC imaging

- Ultrasound is the most sensitive modality for evaluating NEC.

A negative abdominal x-ray does not exclude portal venous gas or intestinal pneumatosis. - Portal venous gas and intestinal pneumatosis is often an early finding, and may also disappear quite rapidly.

The abscence of portal venous gas or intestinal pneumatosis does not exclude NEC. - Carefully examine the whole abdomen with a high frequency linear transducer to evaluate as much bowel as possible.

- Necrotic, thin walled bowel, may look quite similar to healthy bowel.

Look for abscence of peristalsis, mucosal sloughing and hypoperfusion.

Necrotic bowel is usually dilated before it perforates. - The optimal time for surgery is when the bowel has become necrotic, but before perforation occurs. Serial examinations are therefore recommended.

Repeat and Compare

NEC is a progressive disease and imaging should be repeated and compared over time.

Radiography

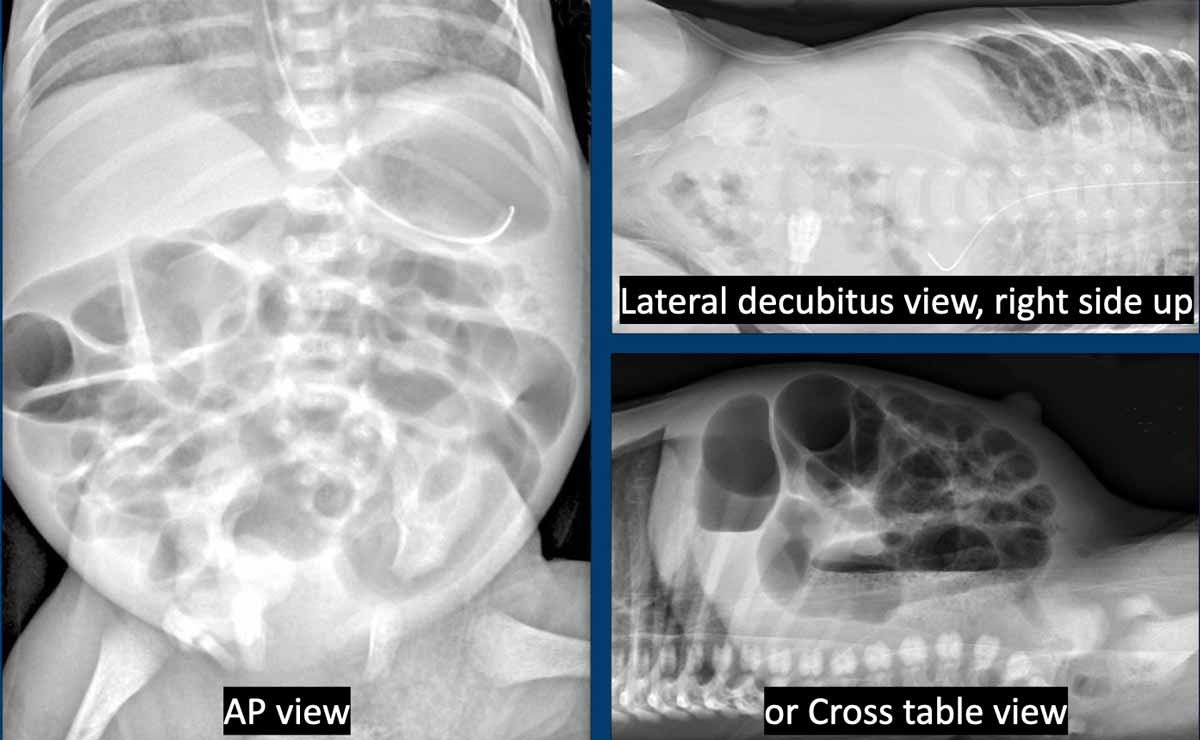

First line imaging is an AP and horizontal beam radiograph, either as a lateral decubitus or cross table view.

The cross table view is preferred as you do not have to move the already sick child and you also get information on what is lying ventrally and what is lying dorsally.

In many cases the radiograph will be inconclusive and ultrasound should be performed additionally.

Ultrasound

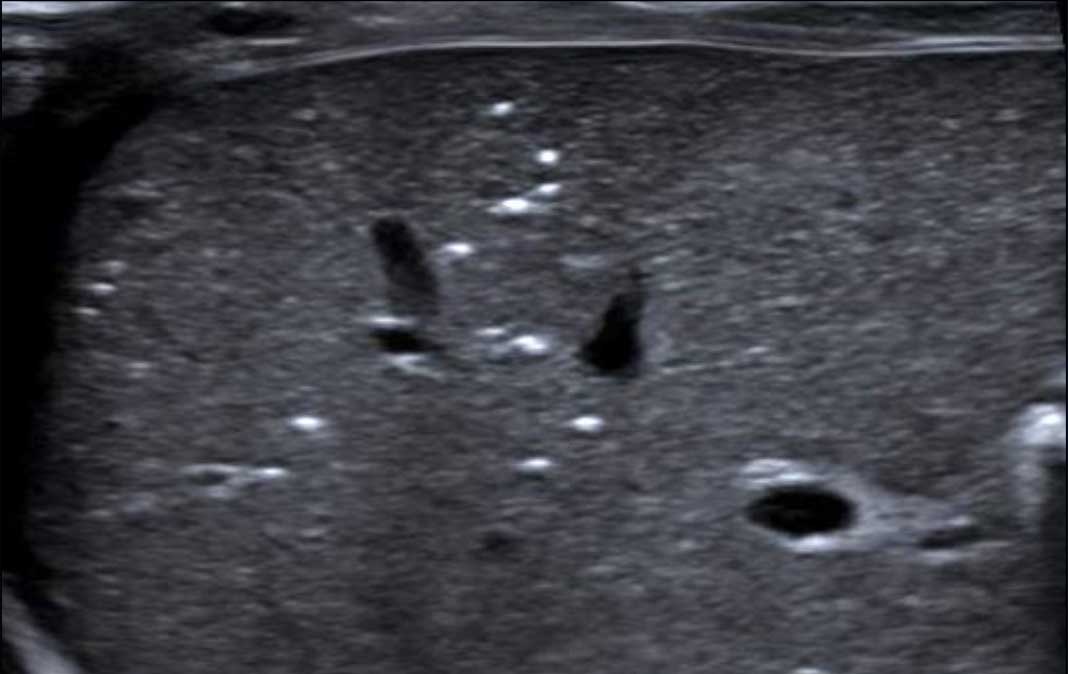

Ultrasound should not only focus on the bowel, but also on the presence

of free fluid (*) and on gas in the portal venous system (arrow).

A negative abdominal x-ray does not exclude portal venous gas or intestinal

pneumatosis.

Pattern of bowel gas

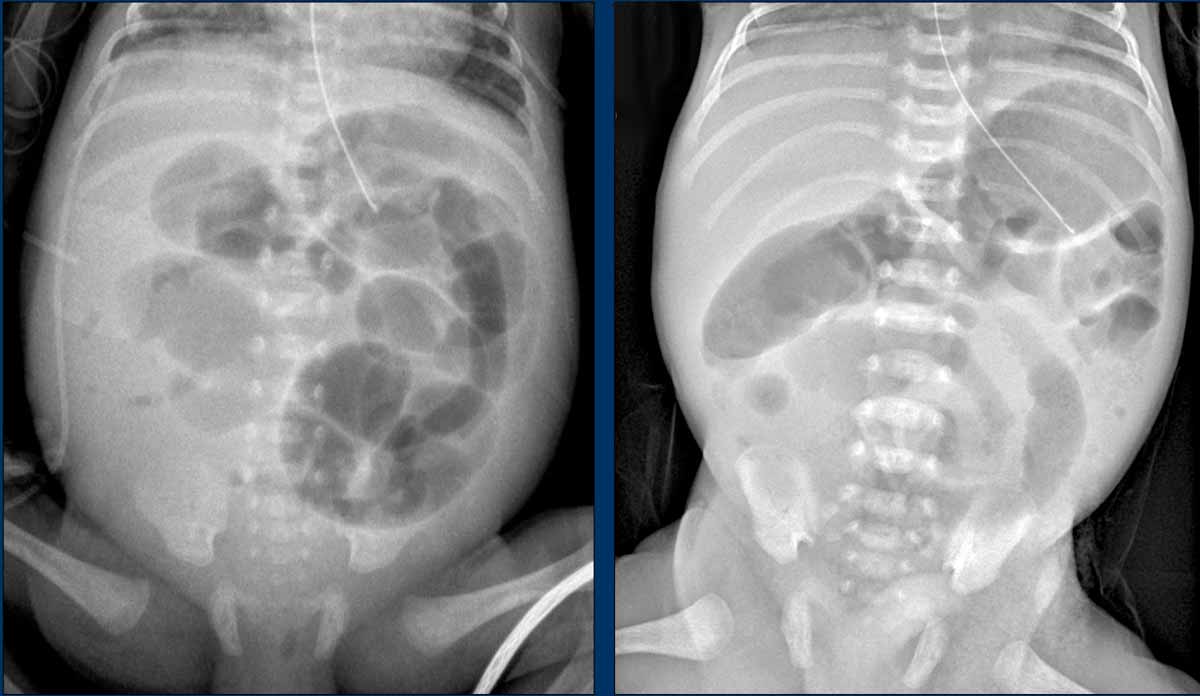

On the radiograph you look for the pattern of bowel gas.

Bowel dilatation

To assess dilatation the interpedicular width of L2 may be used as a reference.

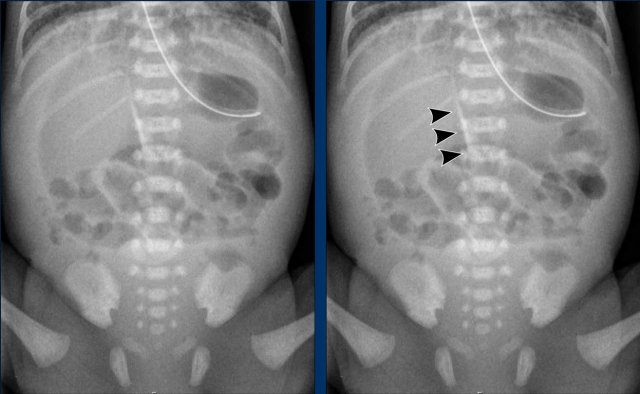

Bowel distribution

Distribution of air should be assessed, as regional paucities of gas may represent diseased bowel.

As the right lower quadrant is the site most commonly affected by disease, this is also the area, that will most often show absence of bowel gas.

Another important sign is the persistent loop.

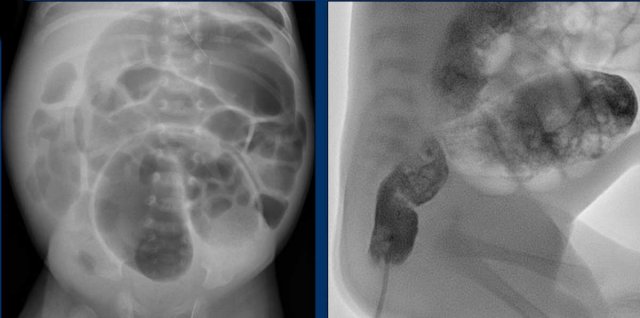

Images

Abdominal radiographs demonstrating dilated bowel loops and asymmetric distribution of air with paucity in the right lower quadrant.

Persistent loop

The persistent loop is a bowel loop, that does not change over time on the radiograph.

This is an ominent sign, consistent with bowel necrosis and thereby a hallmark of impending perforation.

Peristalsis of course, can be best assessed with ultrasound.

Images

Two radiographs taken several hours apart with in the upper abdomen only slightly dilated, but featureless loops, not changing over time. This is a sign of absent peristalsis.

Recommended repeat schedules are between 6-8 hours, but are of course dependent on the clinical situation.

Another example of persistent loops.

Scroll through the images.

No peristalsis

Ultrasound if of course an excellent modality to assess peristalsis and if the radiograph is equivocal you should always do an ultrasound.

Video

Abscence of peristalsis in dilated bowel loops surrounded by ascites.

The arrow points to air bubbles in the ascites, a sign of perforation (discussed below).

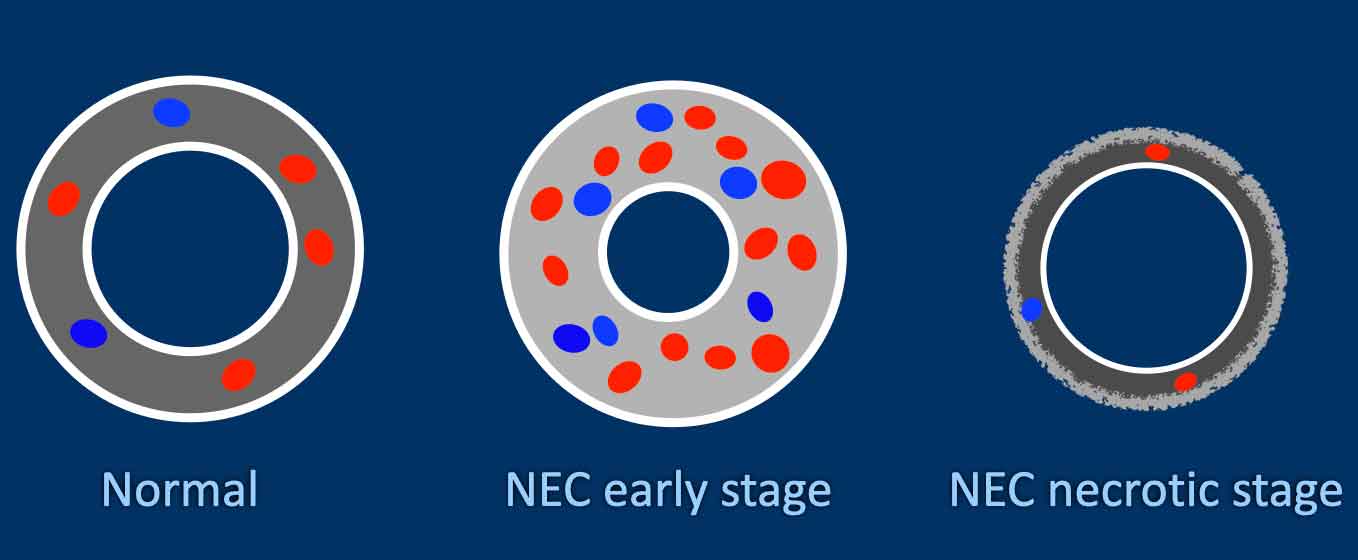

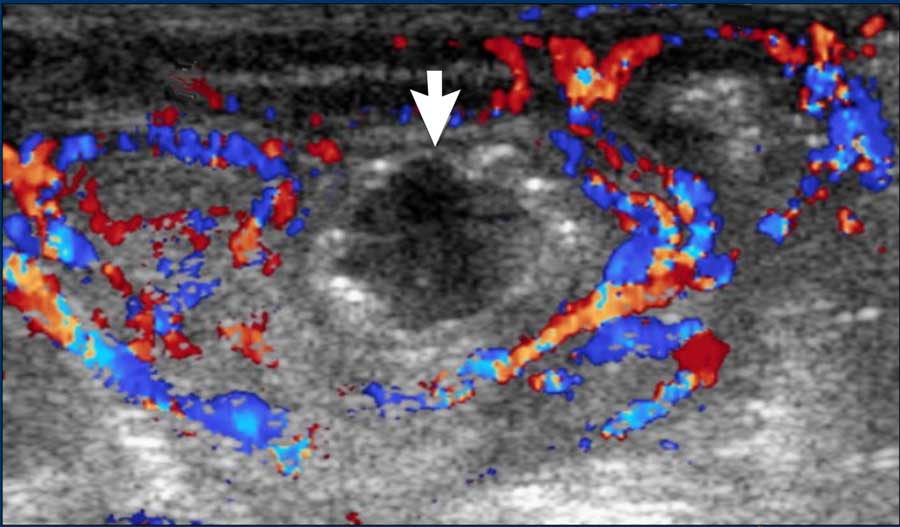

Color Doppler

Assessing the bowel wall requires some experience.

The normal bowel wall has a thickness of less than 2.5 mm and doppler flow is present.

Diseased bowel wall appears thickened (wall thickness > 2.5mm) and the edematous wall has increased echogenicity.

There may be increased doppler flow.

This can be difficult to assess as most sick prematures will be on respiratory support and doppler will be disturbed by artefacts.

In progressive disease, when the bowel becomes fully necrotic, the wall becomes thin (wall thickness < 1 mm) and irregular.

Doppler flow will first reduce and eventually be entirely absent.

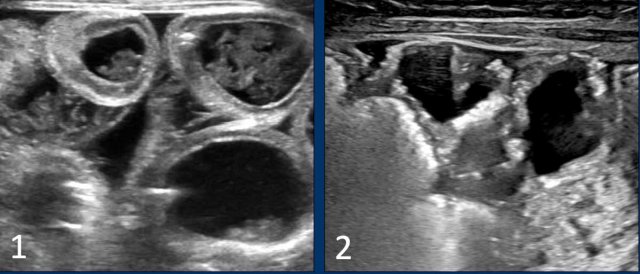

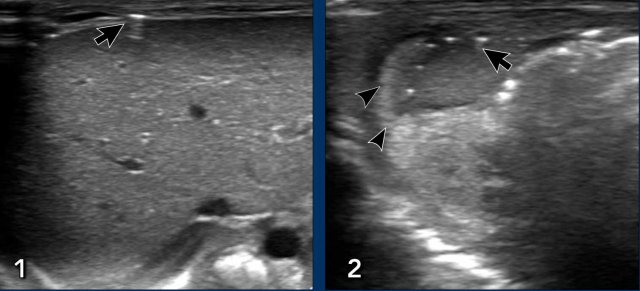

Images

- Diseased bowel wall: thickened and echogenic bowel, with interspersed ascites.

- Thinned and irregular bowel wall in progressive NEC.

Doppler image showing absence of flow and presence of pneumatosis intestinalis.

Courtesy of prof dr M Epelman, RadioGraphics 2007

Pneumatosis

When bacteria invade the bowel, air may be seen in the bowel wall, known as pneumatosis intestinalis.

This is the most typical feature of NEC.

There are some exceptions but this is quite rare and pneumatosis in a premature should be diagnosed as NEC until proven otherwise. Pneumatosis can be seen both on radiographs and on ultrasound.

If you are in doubt whether you are looking at air in the bowel wall or intraluminal air, you just have to remember that air in the bowel wall does not move over time or with slight compression, whereas intraluminal air will move.

Images

Two examples of pneumatosis intestinalis.

Video demonstrating pneumatosis intestinalis.

Portal venous air

When the pneumatosis is taken up into the venous system and transported to the portal vein you can see air bubbles outlining the portal venous system, a ‘pneumoportogram’.

Extensive portal venous air on the radiograph as seen in this case is quite rare.

Ultrasound is superior to radiographs in picking up smaller amounts of air in the portal system.

Air bubbles can be seen as echogenic spots peripherally in the liver, but can also be seen passing by in the portal vein as demonstrated in the video.

Video of portal gas.

Free air

When necrosis progresses to perforation you can see free air or a pneumoperitoneum on the radiograph.

When you see free air on both sides of the bowel wall this is known as Rigler’s sign (arrow).

Football sign

On a supine radiograph free air may be seen under the diafragm outlining the falciforme ligament (figure).

This is known as the football sign, with the ligament representing the laces of an american football.

Of course, when you see any of these signs of free air, ultrasound is not needed anymore, since the NEC has progressed to a perforation and the surgeon should be contacted right away.

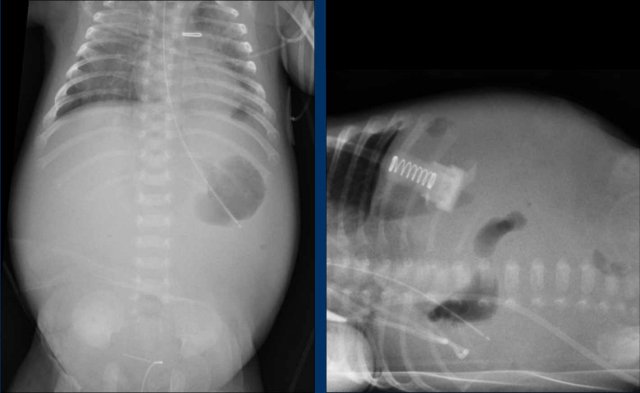

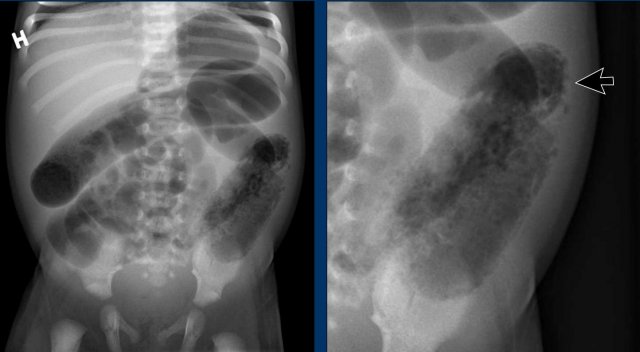

Gasless abdomen

Sometimes a perforation may present with a gasless abdomen.

There is ascites and peritonitis and the bowel is entirely collapsed.

This results in a white abdomen, which is not a good sign.

You may see some free air, as here in the upper abdomen, but sometimes the amounts of free air are too small to appreciate.

Ultrasound may help for further assessment.

Images

There is a nearly gasless or ‘white abdomen’ in a previously normal gas distribution.

There is only a small amount of free air present under the diaphragm.

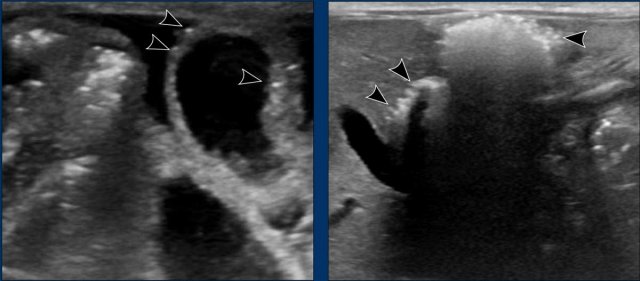

For small amounts of free air ultrasound is more sensitive.

Ultrasound may also show focal and dirty ascites which is very suggestive of a perforation.

Images

- A little air bubble overlying the liver (arrow).

- ‘Dirty ascites’: echogenic ascites (arrowheads) with some air bubbles in the fluid collection (arrows).

Complications

Early start of treatment is important as NEC can be rapidly progressive.

Non-surgical NEC is managed with feeding cessation, gastric decompression, antibiotics and other supportive treatment.

Once a perforation occurs, the surgeon will be contacted as there may be need for peritoneal drain placement or bowel resection.

The mortality in surgical NEC is high, up to 50%.

Long term complications may also occur, such as strictures, malabsorption or short bowel syndrome.

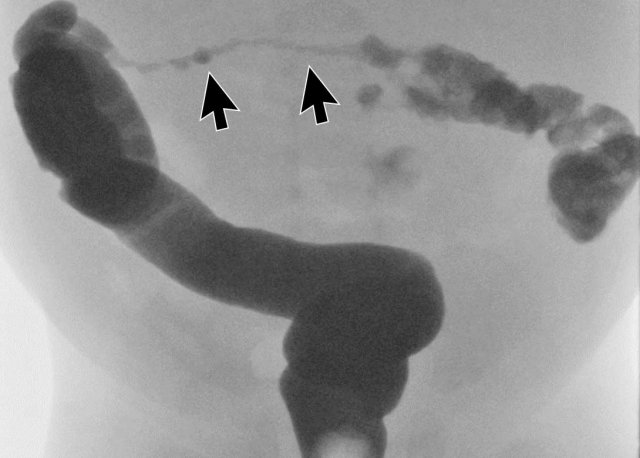

Image

Colonic stricture after NEC (arrows).

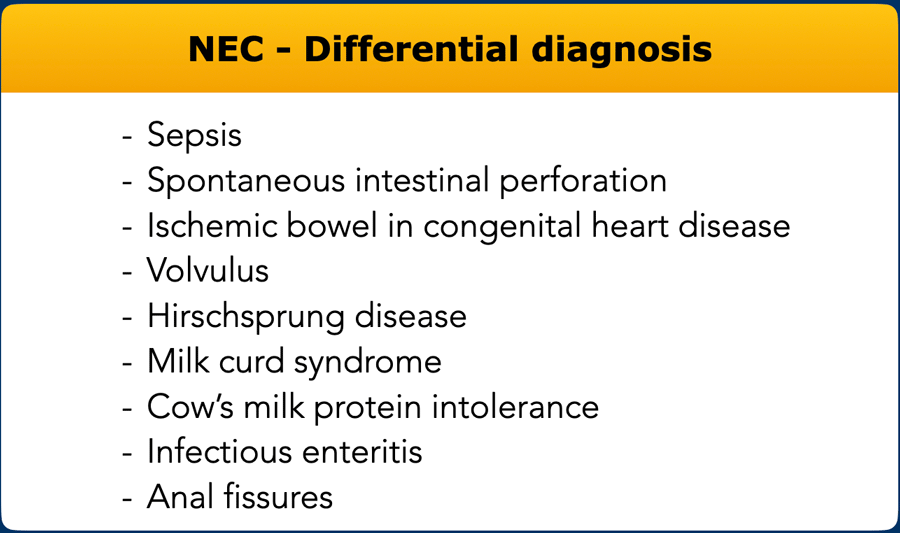

Differential diagnosis

The tabel lists the main differential diagnosis for NEC.

Sepsis

Sepsis is a common disease in prematures due to an immature immune system and is often related to central catheters.

Just like in necrotizing enterocolitis, symptoms may be quite non-specific and also laboratory tests in sepsis are not always clear in the beginning of the disease.

Also, just as in early NEC, radiographs may show dilated bowel loops due to paralytic ileus.

Sepsis and NEC can also be present at the same time and usually with early symptoms the child will be treated for both.

Image

Paralytic ileus in a neonate with sepsis.

Spontaneous intestinal perforation of the newborn

The other main differential diagnosis is spontaneous intestinal perforation of the newborn (SIP).

This typically occurs in very low birth weight infants (<1,5 kg).

SIP is usually seen in the first week of life, which is earlier than most cases of NEC.

The child acutely becomes ill due to a spontaneous perforation.

On imaging you will see a pneumoperitoneum or sometimes a gasless abdomen, but there are no signs of pneumatosis intestinalis or portal venous air.

On surgery, the perforation in SIP is very local, typically at the terminal ileum and in contrast to NEC, the bowel surrounding the perforation looks normal.

Image

Massive free air in a case of spontaneous intestinal perforation.

Ischemic bowel in congenital heart disease

In

children with congenital heart disease there is a risk for intestinal ischemia

due to thrombosis or hypo-perfusion secondary to the cardiac pathology or to

surgery.

The clinical presentation of the bowel ischemia will just be like NEC.

However, the typical age group will not be prematures, but term

babies.

The colon is most susceptible as it relies on the most distal branches

of vascular supply.

Especially the watershed zones (left flexure and

rectosigmoid junction) are at risk.

If no underlying cardiac condition is

known, it should be sought.

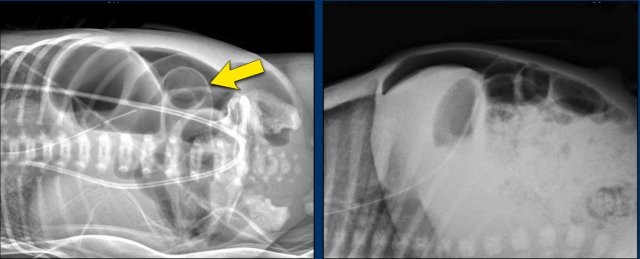

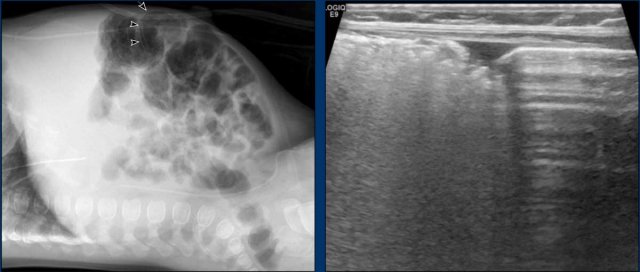

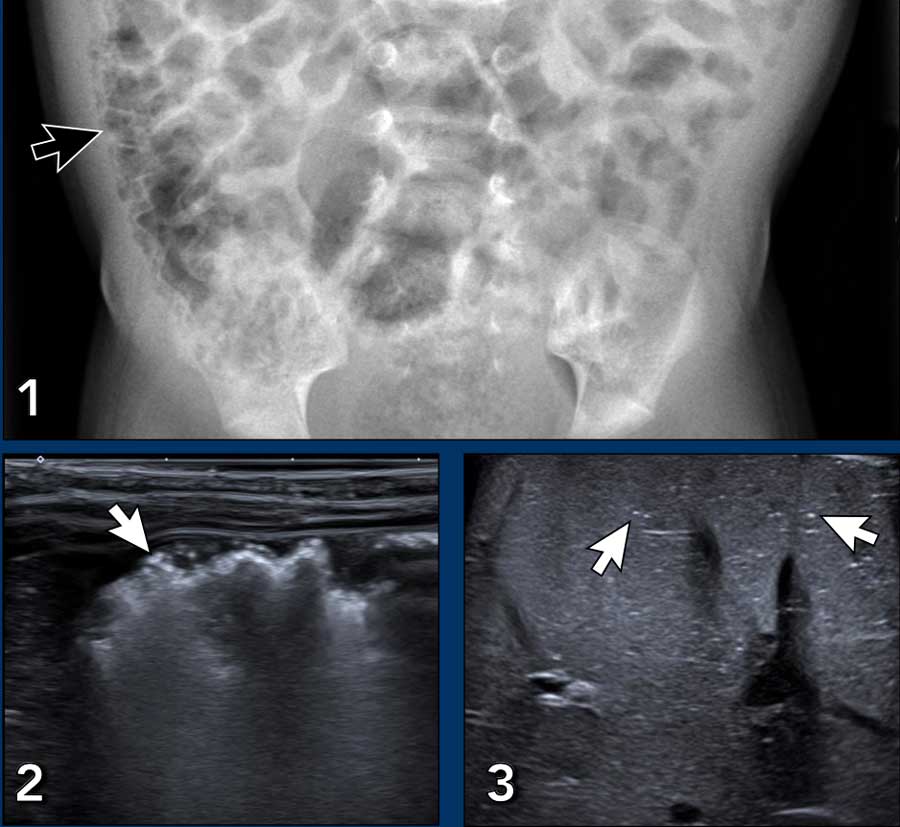

Images

4-month-old

boy operated for complex cardiac disease, now with bloody stools.

Abdominal

x-ray demonstrates pneumatosis in bowel wall (arrow).

This is also seen on

ultrasound in the bowel to the left, whilst the healthy bowel to the right

shows normal air reverberations.

Volvulus

Intestinal malrotation is a congenital condition where the bowel has failed to rotate to its normal position early in embryology.

Malrotation puts the child at risk for volvulus of the bowel and its mesentery, thereby cutting off its blood supply.

This is a serious condition where ischemia may progress rapidly.

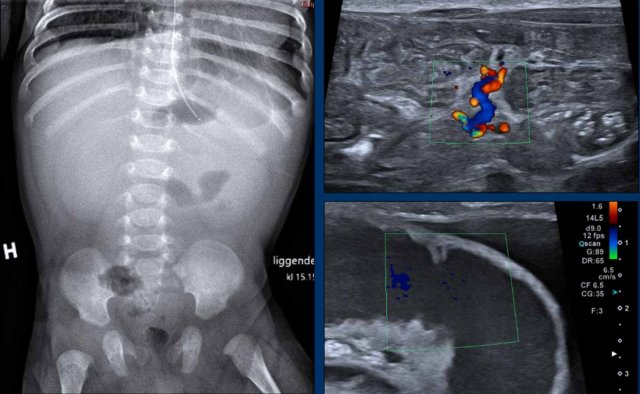

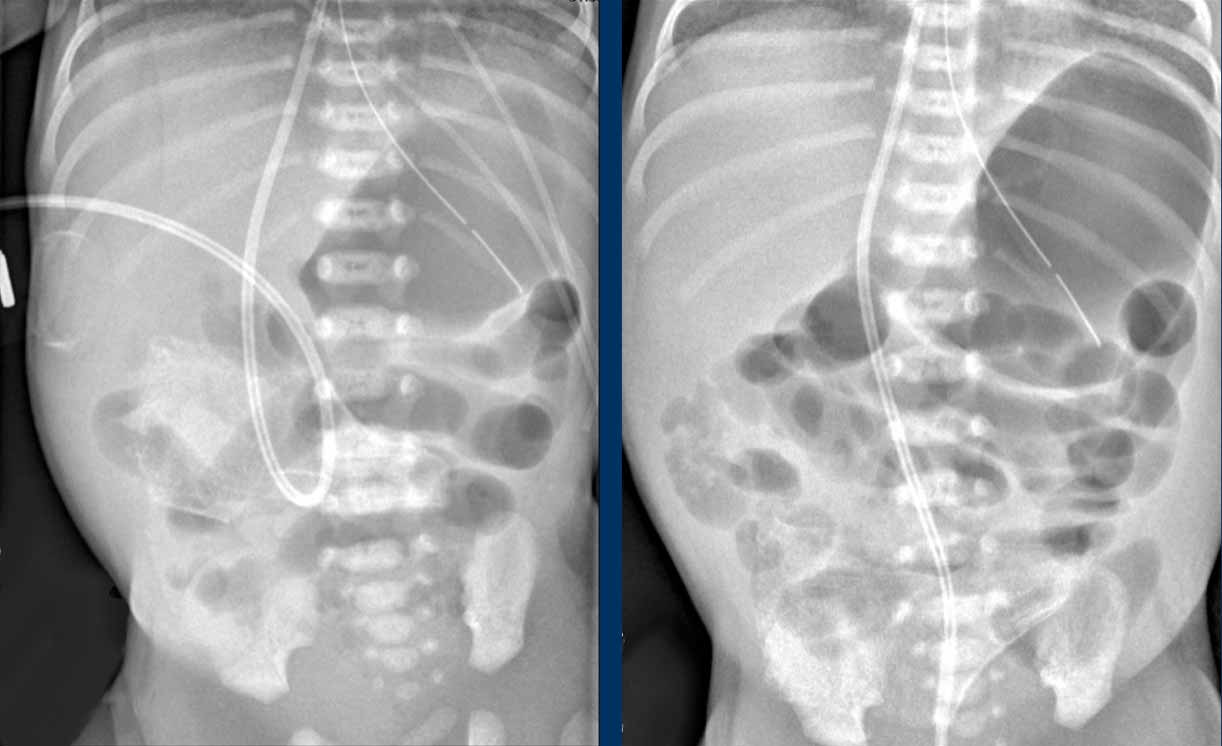

Images

Radiograph of a 2 month old baby with bilious vomiting after diaphragmatic hernia operation. There is very little bowel air consistent with the vomiting and collapsed bowel. On ultrasound ascites and a distended bowel loop with decreased perfusion are seen. In the mesentery a twist of the vessels is seen consistent with volvulus.

Continue with the video of this patient....

For more detailed description of malrotation and volvulus go to 'acute abdomen in neonates'.

Volvulus

Video of a 2 month old baby with heavy vomiting.

There is a vascular twist with the superior mesenteric artery lying to the right of the superior mesenteric vein.

Hirschsprung disease

In Hirschsprung disease there is an absence of ganglion cells in a segment of the bowel leading to a functional obstruction.

The aganglionosis always involves the rectum and may in continuity in oral direction involve a larger segment of the colon.

In most cases the disease is diagnosed in the first 6 weeks of life.

There is a delayed passing of meconium and severe constipation in an otherwise healthy newborn.

Radiographs and contrast enema may confirm the clinical suspicion, but the diagnosis ultimately comes from biopsy demonstrating abscence of ganglion cells.

Image

Bowel obstruction in a newborn with Hirschsprung disease.

The sigmoid is enlarged and there is no air present in the rectum.

On the contrast enema the rectal diameter is smaller than the sigmoid.

A rectum to sigmoid ratio <1 is highly suspicious for Hirschsprung disease.

More cases of Hischsprung disease go to 'acute abdomen in neonates'.

In rare cases when Hirschsprung disease is not recognized and not treated correctly, severe bowel wall inflammation may develop.

Rarely this may cause bloody stools and pneumatosis intestinalis – thereby mimicking NEC.

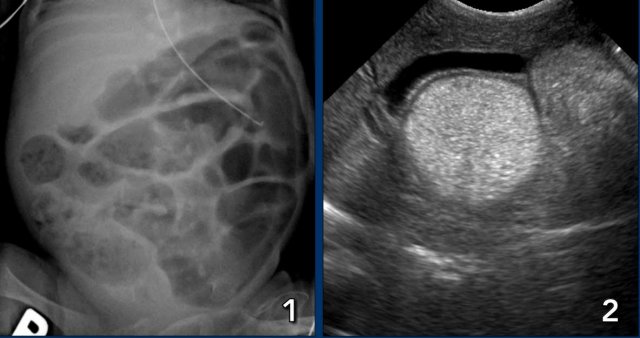

Milk curd syndrome

Milk curd syndrome is bowel obstruction due to inspissated milk or ‘lactobezoar’.

For unknown reasons lactobezoar occurs more often in prematures than in term babies.

It occurs after the first week of live, when feeding has increased.

There is bowel obstruction, but the neonate is otherwise doing fine. On the radiograph you may see bubbly lucencies that may resemble pneumatosis, but bubbles are not clearly seen in the bowel wall. Ultrasound will confirm the presence of thick hyperechoic intraluminal content in otherwise healthy bowel.

Treatment will in most cases just be an enema.

Images

- Bubbly lucencies due to lactobezoar in the right lower quadrant in an infant with milk curd syndrome. The finding may cause concern for pneumatosis intestinalis.

- Ultrasound demonstrates healty bowel, there is no pneumatosis intestinalis, but there are clearly thick intraluminal contents.

Cow’s milk protein intolerance

Cow’s milk protein intolerance is not a diseaes of prematures, but occurs in older children.

It is a relatively common allergic enterocolitis.

The allergy will be accompanied by a rash.

Sometimes there may be confusion as also in cow’s milk protein intolerance in severe cases infants may have bloody stools and radiographs in severe enterocolitis can show pneumatosis intestinalis as shown this case.

Of course, the sick bowel first needs bowel rest, before upstart of an extensively hydrolyzed formula.

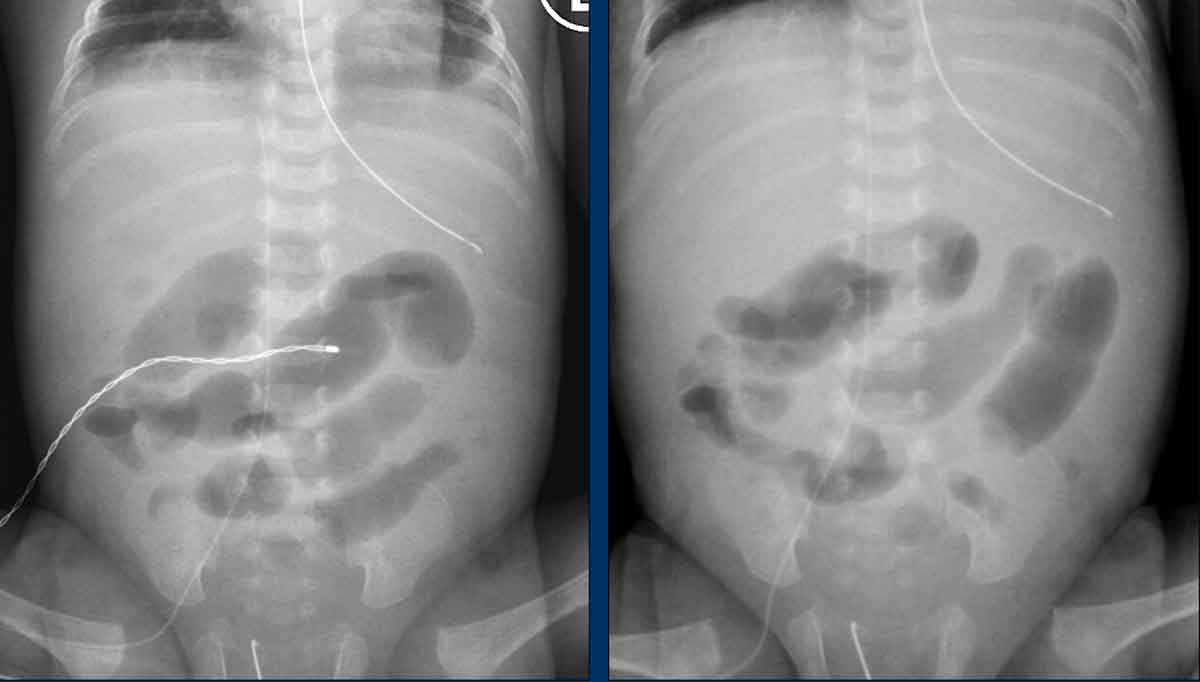

Images

The arrows point to pneumatosis intestinalis on the radiograph and ultrasound, and to portal venous gas on the third image.