Abdominal wall hernias

Marc Engelbrecht, Simba Timmer, Erwin van Geffen and Robin Smithuis

Radiology department of the Amsterdam Medical Center, Department of Surgery Jeroen Bosch hospital and the Alrijne hospital in Leiden

Abdominal hernias are usually a clinical diagnosis and have been considered a simple

problem to be repaired.

However, long-term follow-up of patients has shown

disappointing results, both in terms of complications and recurrence (1).

Due

to increased complex abdominal wall surgery, pre-operative CT planning with

abdominal wall mapping has gained increasing attention.

In this article we will

adress the key imaging features of complex abdominal wall hernias.

Introduction

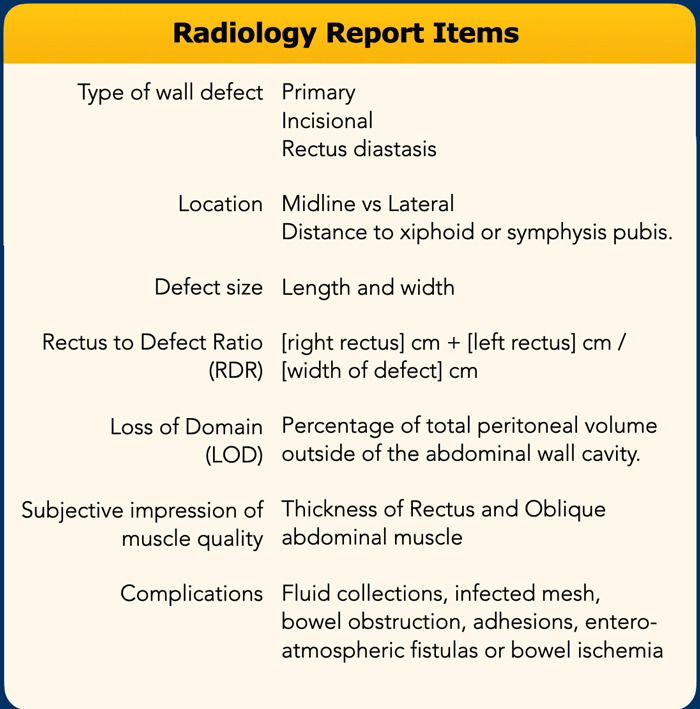

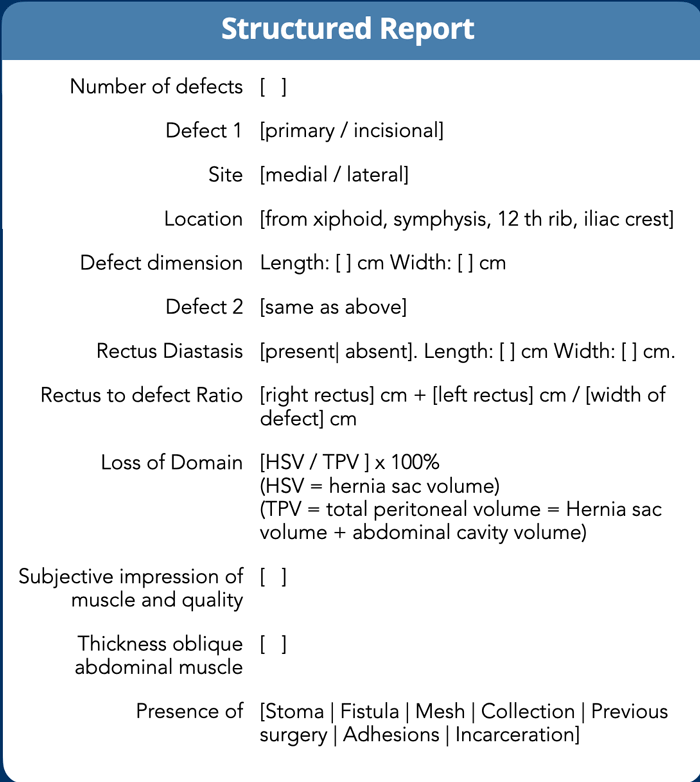

Structured Radiology Report

What the surgeon needs to know is:

- Exact location, size and number of defects.

- Condition of the abdominal wall musculature and the ratio between the defect and the width of the rectus muscles (RDR).

- Volume of the hernia sac in relation to the total peritoneal volume, also called "loss of domain", in order to determine whether there is enough space to reduce all herniated contents into the abdominal cavity without risk of recurrence or ventilatory restriction.

In the table you will find the most important items, that need to be addressed in the radiology report.

All these subjects will be discussed in this order in the next chapters.

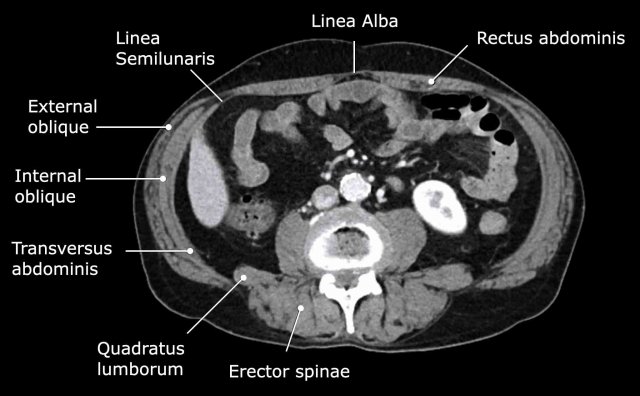

Abdominal wall musculature

Important muscular structures that surround the abdominal organs are shown in this figure.

The linea alba is a line

formed by the aponeuroses of the right and left rectus muscle and connects both

muscles in the midline.

As the linea alba is an avascular area, it is

frequently used as point of entrance for open abdominal surgery.

The linea semilunaris is a curved tendinous line that is located lateral to the rectus

abdominis muscle on both sides.

Here, the anterior and posterior rectus sheaths

connect with the three lateral abdominal wall muscles: the external oblique,

the internal oblique and the transverse abdominal.

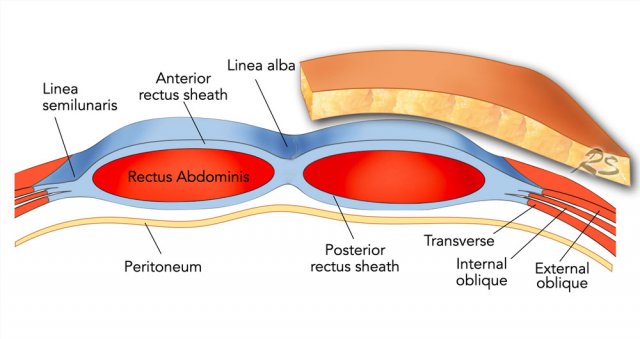

This illustration demonstrates how the anterior and posterior rectus

sheath are formed by the aponeuroses of the external oblique, internal

oblique and transverse abdominal muscles.

Because abdominal

wall hernias are defects of the fascia of the abdominal wall, these fascia layers need to be brought

together during surgery.

Therefore, the rectus sheaths play an important role

in surgical hernia repair.

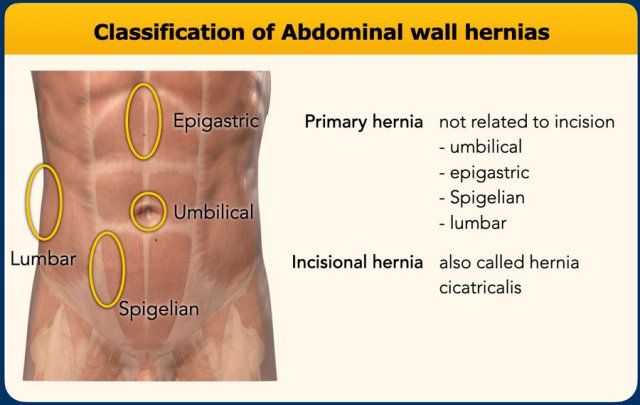

Type of abdominal wall defect

Primary hernia

Abdominal wall hernias can be divided into primary hernias, that are not related to incisions and incisional hernias.

Primary abdominal hernias are hernias, that are located at certain weak spots in the abdominal wall.

In the midline are the umbilical and epigastric hernia and lateral are the Spigelian and lumbar hernia.

The Spigelian hernia is an uncommon hernia at a weak spot between the oblique abdominal muscles and the rectus abdominis.

Primary lumbar hernias are uncommon and are also located lateral but more posteriorly, where there is a weak spot between the oblique abdominal muscles and the quadratus lumborum. They can be divided into

superior and inferior lumbar hernias (Greenfellt-Lesshaft and Petit).

Incisional hernia

Incisional hernias are the most common and can be located anywhere, where there has been an incision, drain opening, trauma or prior repair of a primary hernia.

Most incision hernias are located in the midline.

Incisional hernias in the lumbar region can be seen after nephrectomy, hepatopancreatobiliary, or aortic-surgery.

Examples of abdominal wall hernias:

- Umbilical hernia with protrusion of mesenteric fat. This hernia is the most common.

- Spigelian hernia situated at the linea semilunaris. This hernia is uncommon and is frequently incomplete, meaning that the hernia is ‘covered’ by the intact external oblique.

- Epigastric hernia, midline hernia above the level of the umbilicus (*)

- Inferior lumbar hernia of Petit.

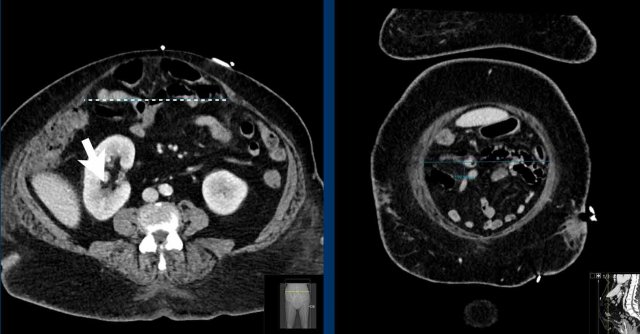

Rectus diastasis

Rectus diastasis is a widening between the left and

right rectus muscle with protrusion of visceral fat or bowel (figure).

The difference with a hernia is that in diastasis there is no fascia defect.

A gap of

> 2,0 cm between left and right rectus muscle is considered diastasis.

Besides transverse width, craniocaudal length of the diastasis should be measured as well.

Rectus

diastasis in men is often caused by increased visceral fat and in women due to

pregnancy.

Abdominal wall hernias may coexist with diastasis.

Diastasis is important to mention as hernia recurrence is more likely in the presence of rectus diastasis.

Location and size of the defect

The number of defects and the location of the defect should

be reported.

As mentioned before, hernias are classified as midline as long as they are located

within the lateral borders of the rectus sheath (e.g. the linea semilunaris). Lateral

hernias are located lateral to the linea semilunaris.

A description of the size of the abdominal wall

defect is needed for pre-operative planning.

The size consists of width and

height.

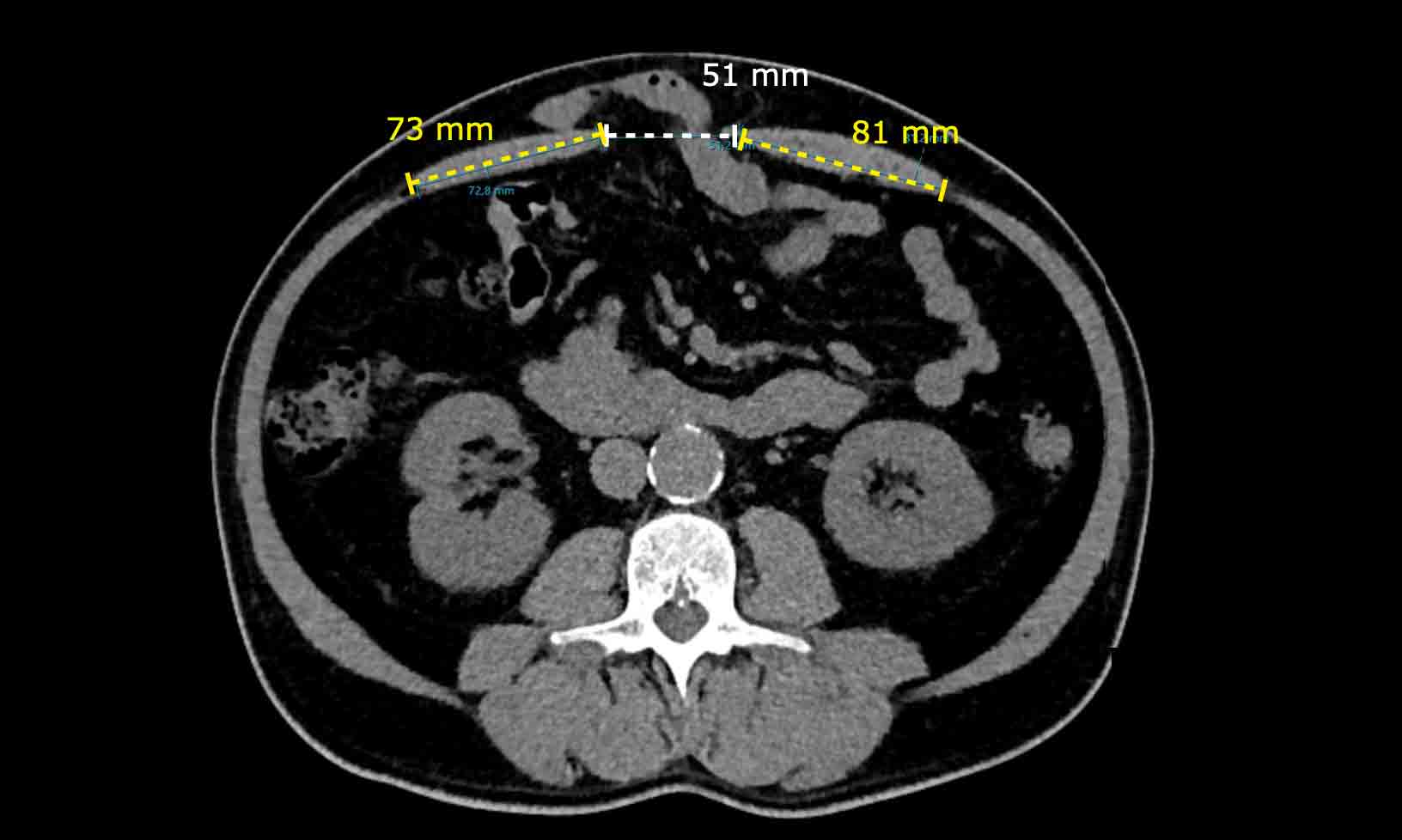

Here a schematic illustration of the measurements

of the defect in two axes: longitudinal and transverse (see Figure).

For

midline hernias cranio-caudal location can be described by the distance to the

xiphoid or symphysis pubis.

For lateral hernias, cranio-caudal location

can be described by distance to the costal margin or iliac crest.

When multiple defects are present, the combined length and width of all the

defects should be reported because multiple defects are normally treated as one

functional defect (like Swiss Cheese).

However if hernias are located

relatively far away, they can be described as separate hernias.

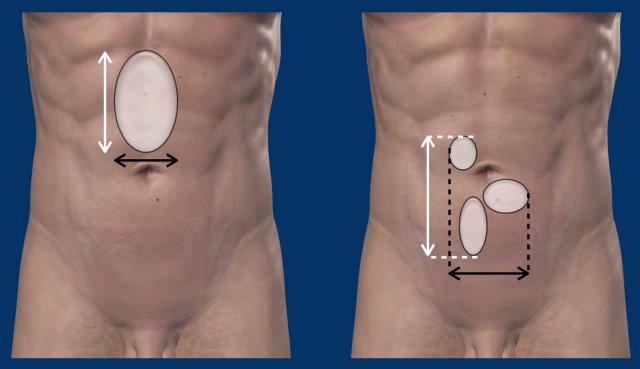

Here an example of the measurement of the defect

size.

The hernia width is the maximum distance in between the rectus muscles,

measured on the axial view at which this distance is largest.

The defect height

is the maximum cranio-caudal distance, measured in the sagittal plane.

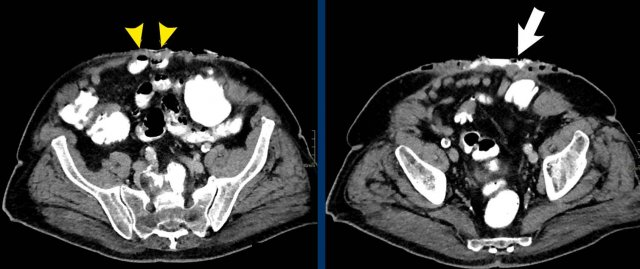

Measurement of multiple hernias

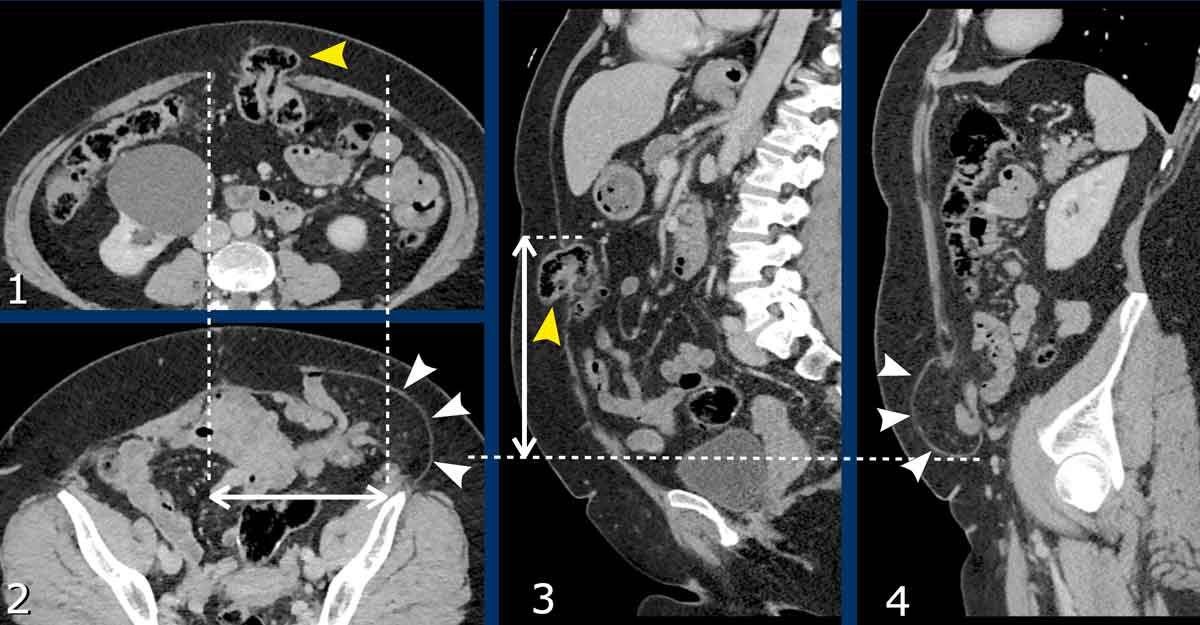

This patient has two hernias.

There is a midline hernia (yellow arrowheads) and a lateral hernia (white arrowheads).

in this case the total combined length and total width are measured.

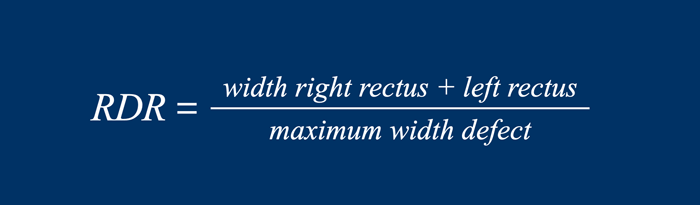

Rectus to Defect Ratio

The Rectus to Defect Ratio (RDR) is the ratio of

the sum of the width of the left and right rectus compared to the hernia width.

Another name for this equation, often used by surgeons, is the Carbonell-index named after Prof Alfredo Carbonell who first published this.

The RDR is a practical and reliable tool to predict the ability to close the abdominal wall defect during routine hernia repair without the need to perform an additional component separation technique (CST).

Component separation technique is a surgical techniques in which one of the three lateral muscles is transsected from the others.

These techniques ‘loosen’ the remaining abdominal wall, but are associated with a higher risks of postoperative complications (see treatment).

If the RDR is > 2, routine surgical repair will be able to close the abdominal wall defect in 90% of cases.

If the RDR is < 1.5, in more than 52% of the repairs, additional component separation technique is required.

Image

In this

patient the Rectus to Defect Ratio: (49 mm + 43 mm) / 157 mm = 0.58.

This ratio predicts

that hernia closure will probably not be possible without performing a component separation technique.

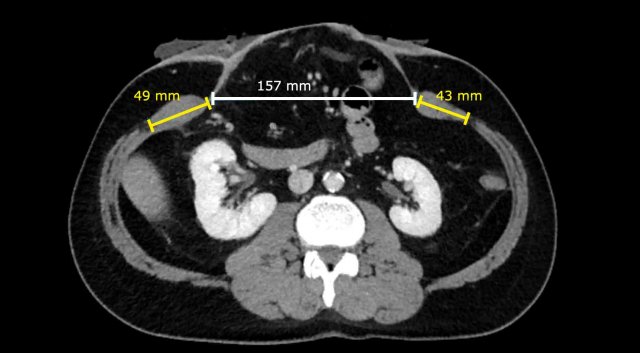

Image

In a different patient, the Rectus to Defect Ratio

is: (73 mm + 81 mm) / 51 mm = 3.

Contrary to the previous case, hernia closure will be possible without performing a component separation technique.

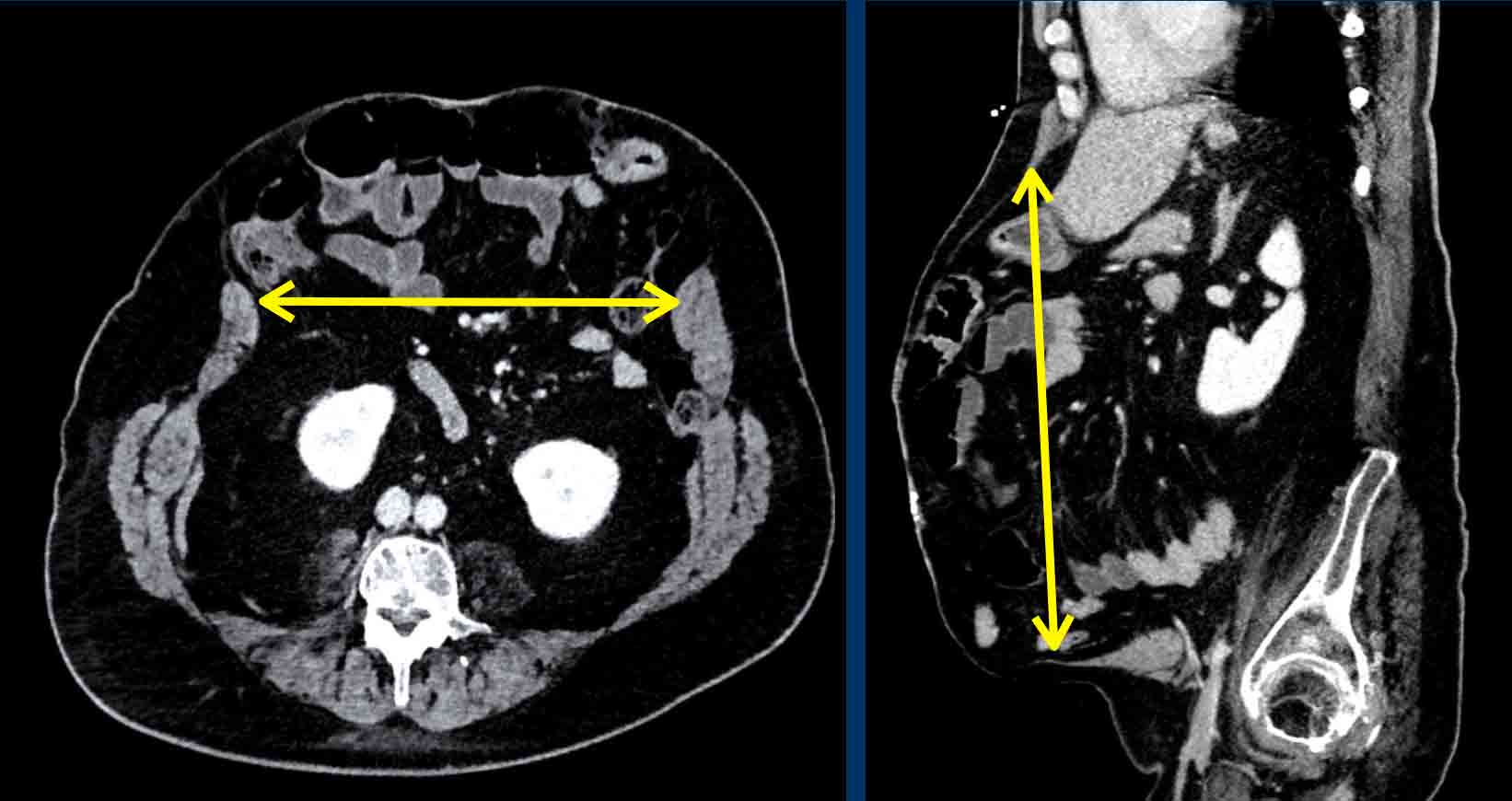

Loss of Domain

Loss of domain is a ratio that describes the amount

of peritoneal content that is located in the hernia sac.

This ratio is used to

predict the risk of peri-operative complications as well as the need for preoperative

botulinum injections and/or component separation technique.

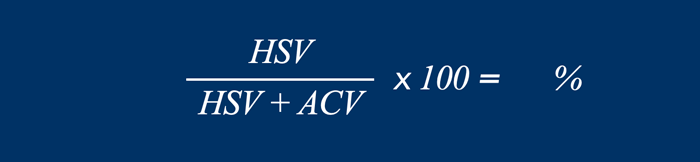

This ratio is calculated by dividing

the hernia sac volume (HSV) by the total peritoneal volume (TPV).

The total

peritoneal volume consist of the hernia sac volume plus the

abdominal cavity volume (ACV).

For more information on preoperative botox

injections: see treatment.

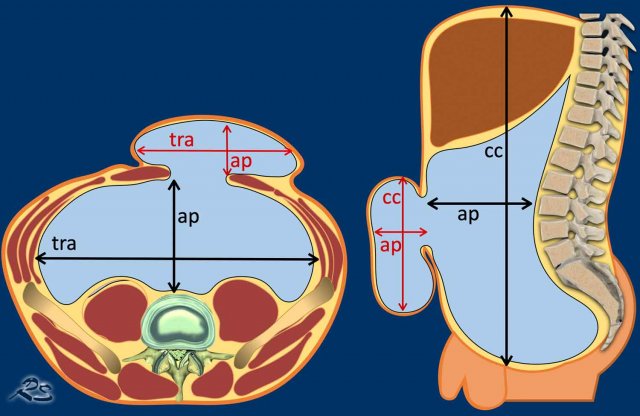

The specific volumes can be obtained through volume

rendering or with a simplified method to

estimate the volumes, i.e. the height, width and depth of the hernia and abdomen

are multiplied by 0.52 (the formula of an ellipse).

- HSV= cc x tra x ap x 0.52

- ACV= cc x tra x ap x 0.52

The height of the abdomen is measured from the

upper edge of the liver to the symphysis, the width is measured in between the

transversus abdominal muscles on both sides.

The depth is measured from the

anterior side of the vertebral column to the anterior abdominal wall.

If the anterior abdominal wall is no longer present, due to a large ventral hernia, extrapolation of the remnant anterior abdominal wall may be done, so abdominal depth may be measured.

The

height, width, and depth of the hernia are measured within the hernia sac.

For

more information on Loss of Domain measurments see ref 6.

If the loss of domain is larger than 20 %, there is a high risk of surgical complications and abdominal wall repair will result in increased abdominal cavity pressure with complications such as respiratory failure and hernia recurrence (ref 7 and ref 8).

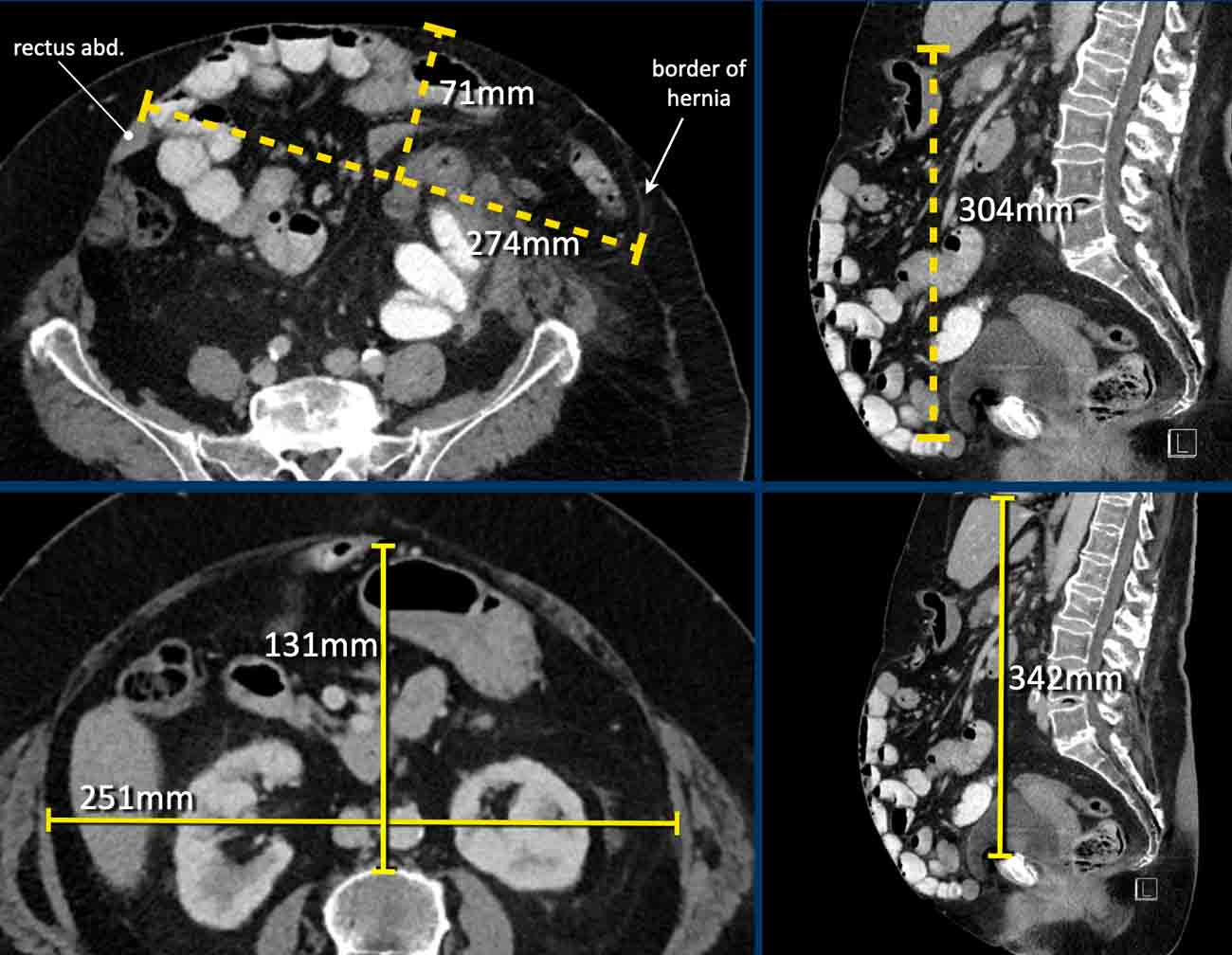

Image

In this patient the loss of domain is > 20% and additional strategies will be necessary to increase the abdominal capacity and compliance.

In this patient with a large hernia, the measurements are as follows:

- Hernia Sac Volume = (274 x 71 x 304 mm x 0,52) x 10-6 = 3.1 liter.

- Abdominal Cavity Volume = (251 x 131 x 342 mm x 0,52) x 10-6 = 5.8 liter.

- Total Peritoneal Volume = ACV + HSV = 3.1 + 5.8 = 8.9 liter.

The loss of domain in this case is the volume of the hernia sac divided by the volume of the total peritoneal cavity:

3.1: 8.9 = 35%.

This is far greater than 20% and means that there is a high risk of complications during and after a simple abdominal wall repair.

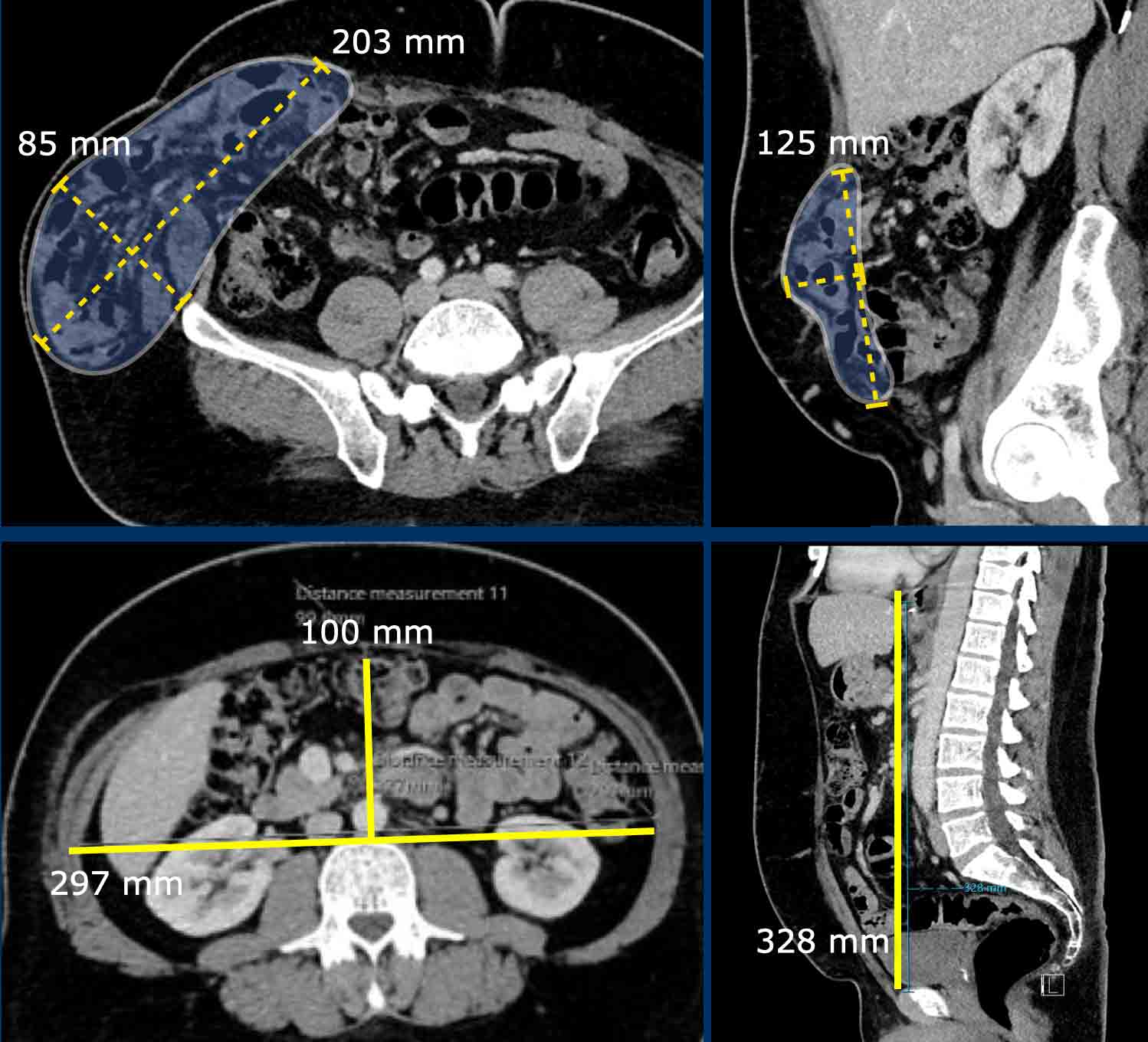

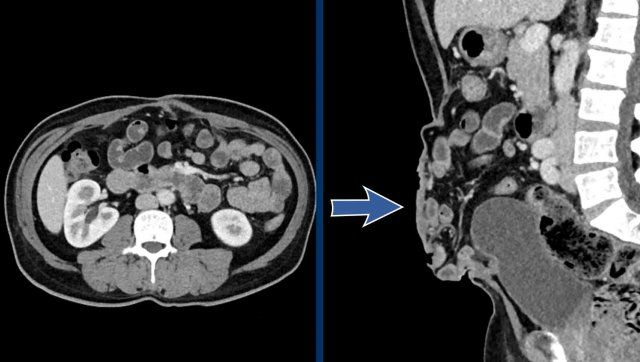

In this patient with a hernia, the measurements are as follows:

- Hernia Sac Volume = (203 x 85 x 125 mm x 0,52) x 10-6 = 1.12 liter.

- Abdominal Cavity Volume (ACV) = (297 x 100 x 328 mm x 0,52) x 10-6 = 5,1 liter.

- Total Peritoneal Volume = ACV + HSV = 5.1 + 1.12 = 6.2 liter.

Loss of Domain = 1,12 / 6,2 x 100% = 18 %

Complications

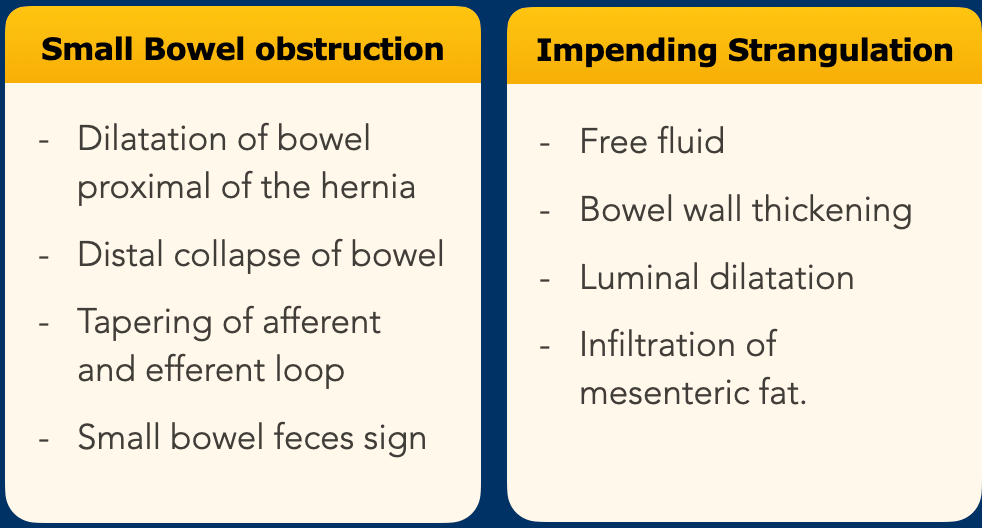

Incarceration

The most

serious and acute complication is an incarcerated hernia.

An incarcerating

hernia can be diagnosed by looking at two separate features, namely small

bowel obstruction and signs of impending strangulation.

Actually these are all signs of closed loop obstruction, which is the cause of the strangulation.

You will find more information about closed loop obstruction here.

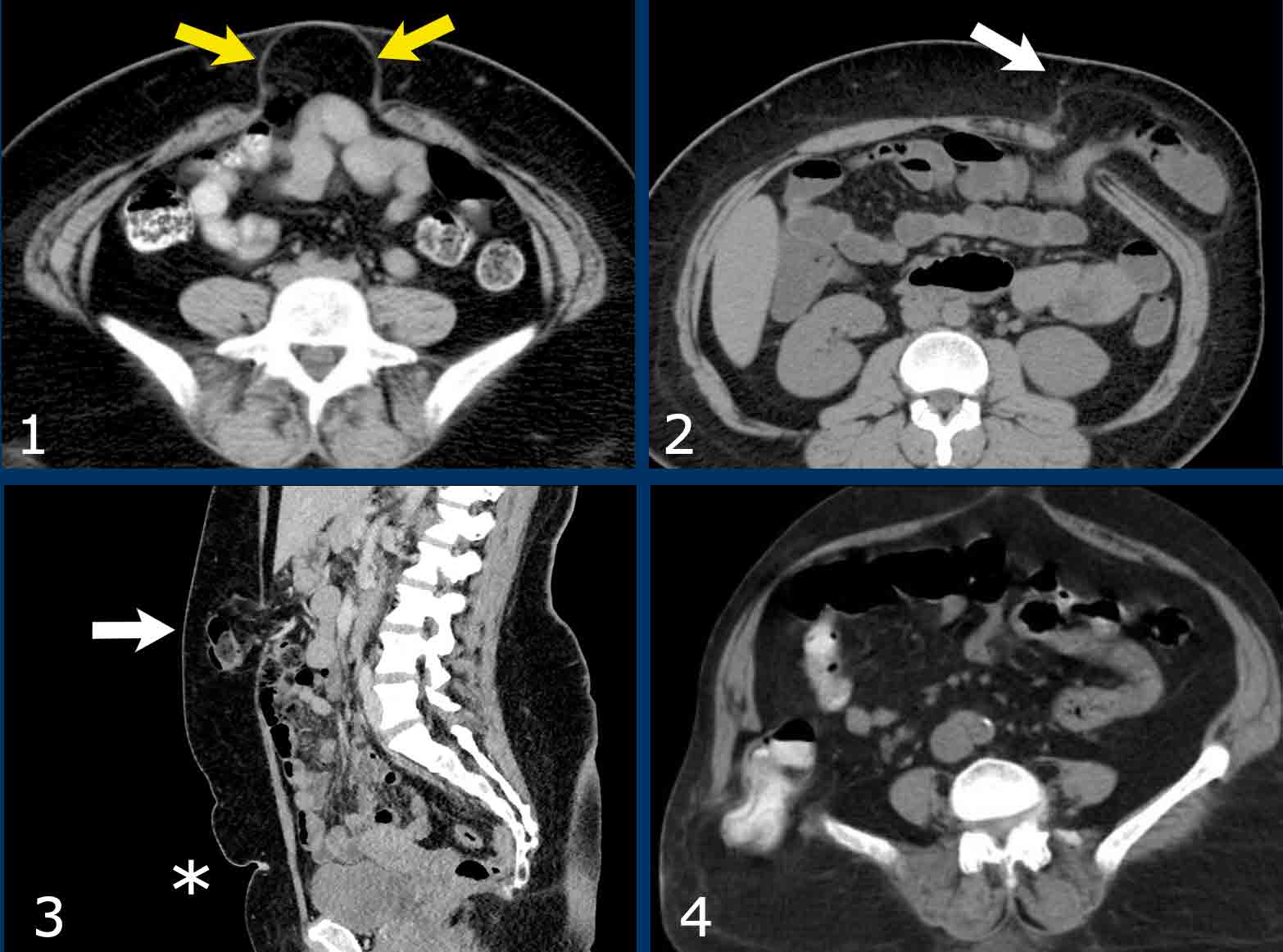

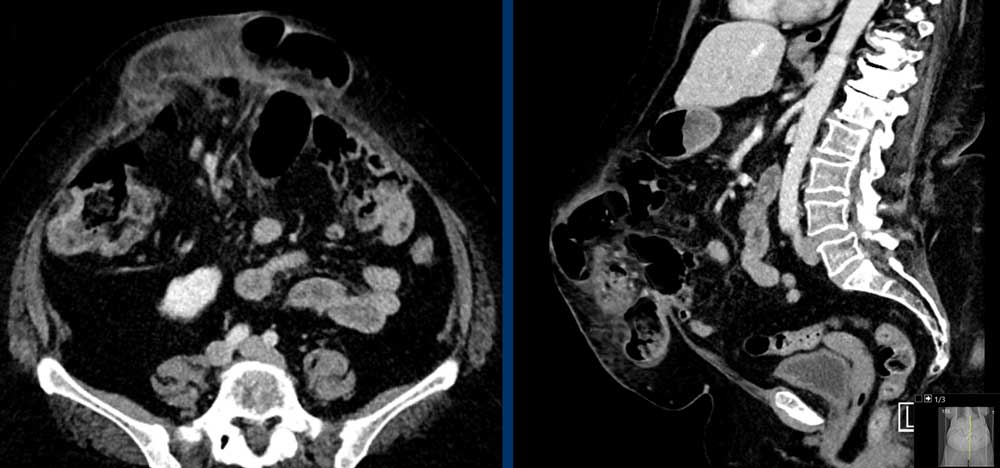

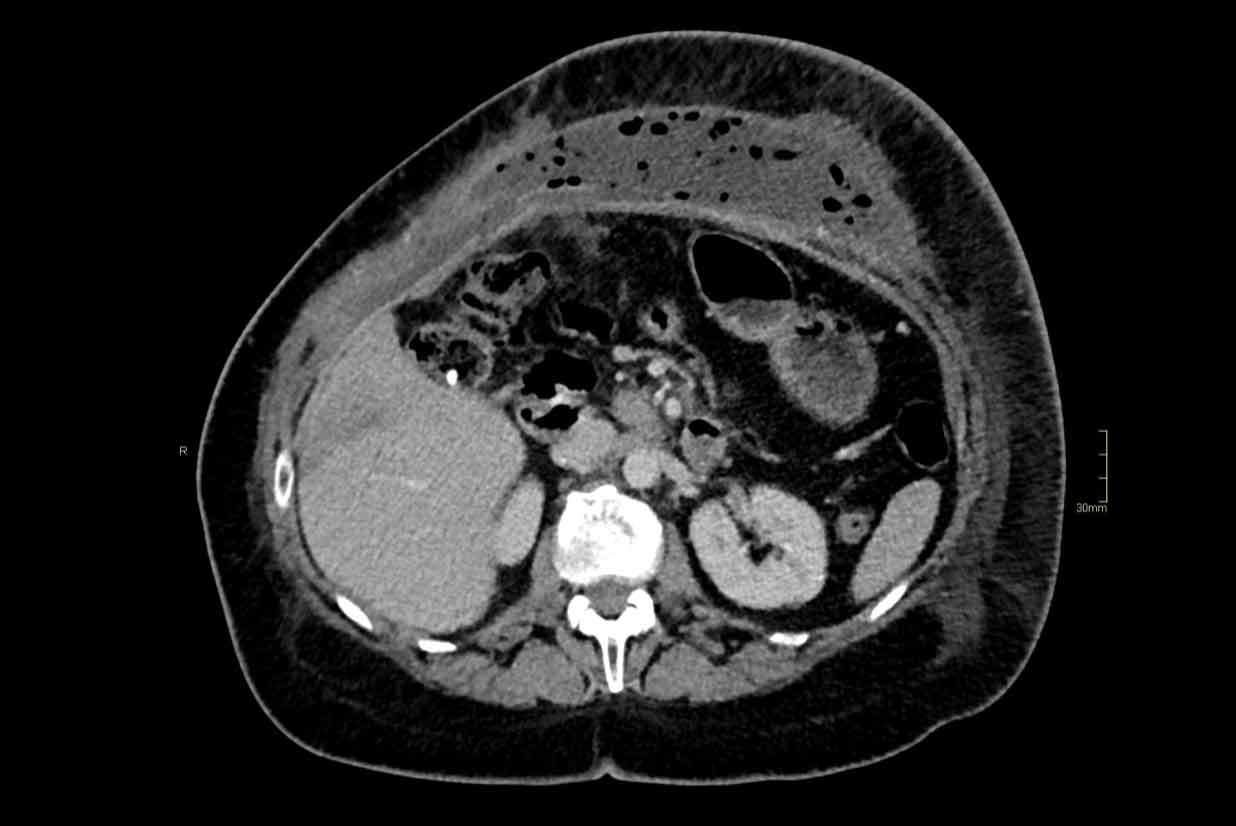

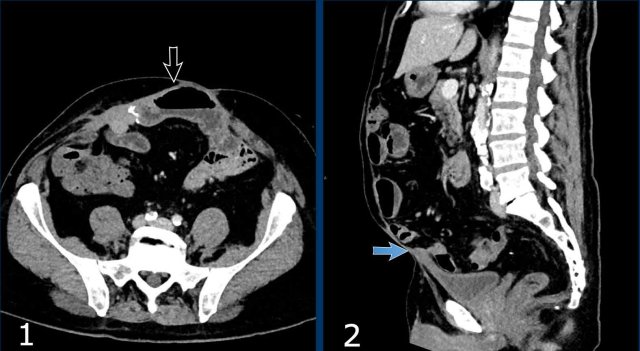

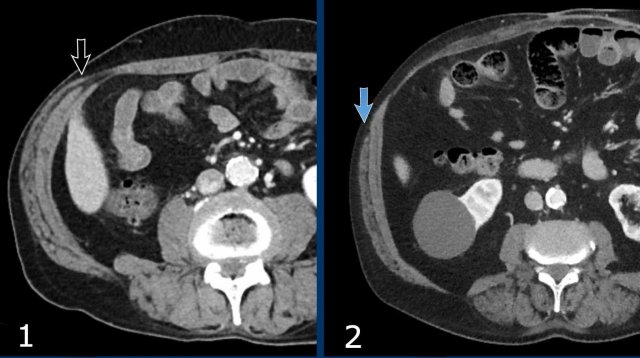

These images are of a 78 year old morbid obese female who has an incisional midline hernia.

Study the images and then compare to the next images, who were taken one month later, when she presented with a painfully swolen hernia.

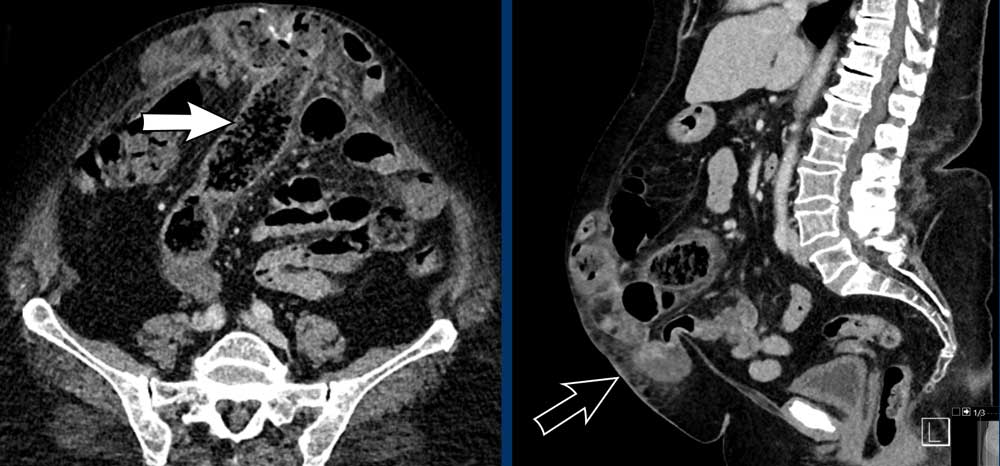

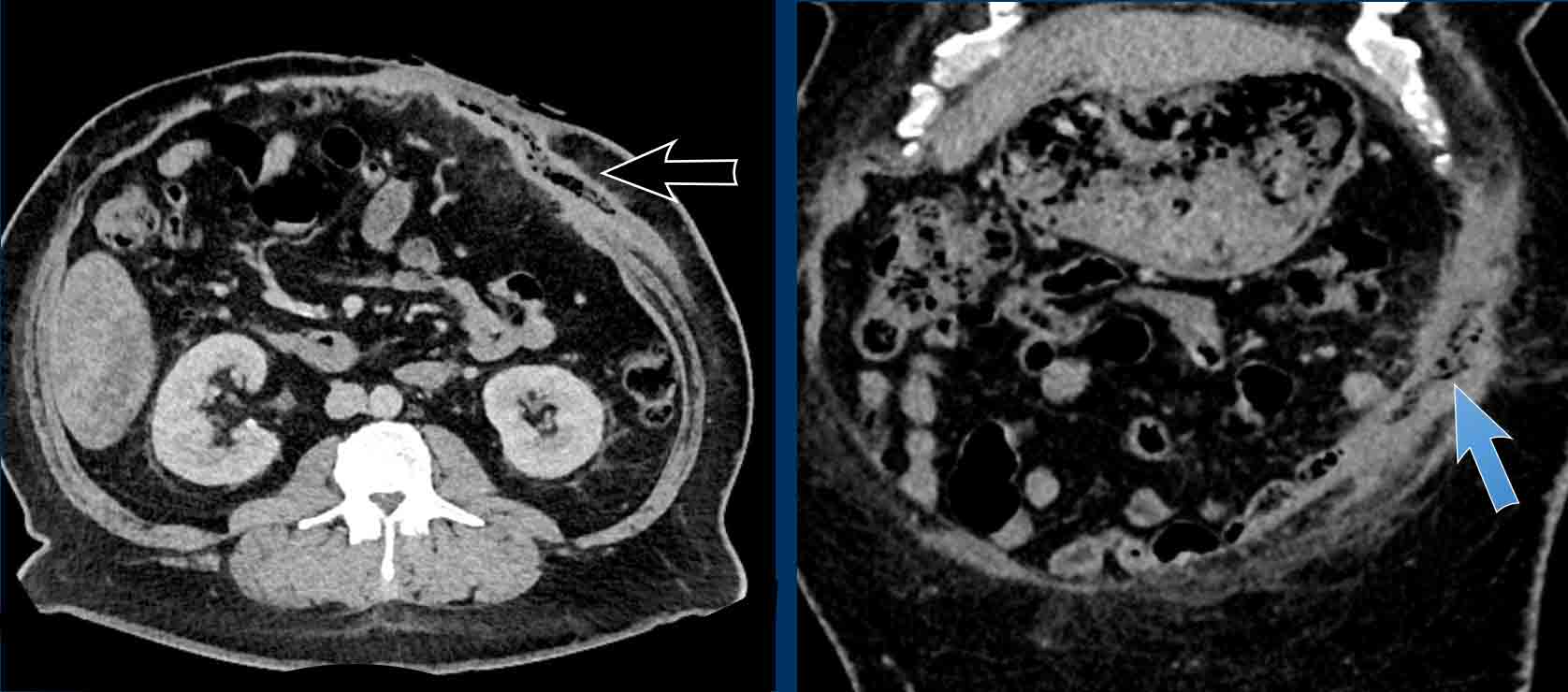

Now there are signs of strangulation namely:

- New small bowel feces sign, best see on the transverse images (white arrow).

- Infiltration of mesenteric fat (black arrow).

As in any hernia that contains bowel, strangulation in abdominal wall hernias occurs as a result of closed loop obstruction with venous infarction.

Image

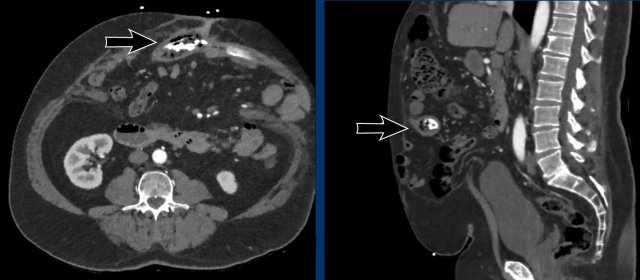

This patient has a hernia that contains small bowel.

The defect is rather small and there is a stenosis at the point where the bowel enters the hernia sac (yellow arrow) and where it exits the hernia (white arrow).

These two stenosis are proof of a closed loop obstruction.

There is dilatation of the bowel and fat infiltration as a result of ischemia resulting from venous obstruction.

Continue with the video...

The video better demonstrates the two stenoses.

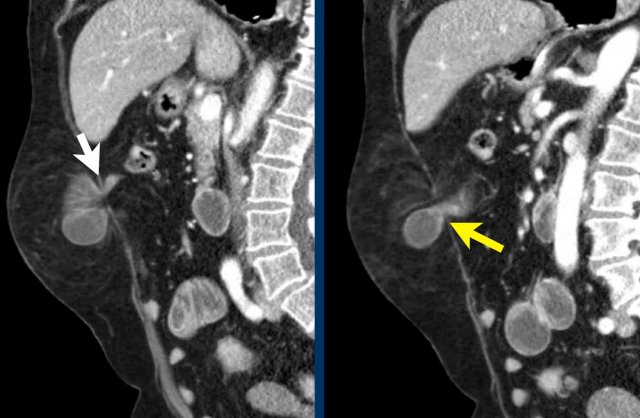

This is another example of a closed loop obstruction within the hernia sac.

The white arrow indicates the first obstruction, where the bowel enters the closed loop.

The yellow arrow indicates the exit.

In this case the closed loop is caused by adhesions within the hernia sack.

Notice the fat infiltration and the dilated loops with slightly hyperdense walls.

These are all signs of bowel ischemia.

Immediate laparotomy was performed.

The bowel within the hernia sac was ischemic and had a purple color, but after cleavage of the adhesions, the color of the bowel returned to normal.

Mesh infection

A common complication

of abdominal wall surgery is the development of a fluid collection.

It is

important to differentiate sterile collections like hematoma and seroma from an abscess

Image

This patient had abdominal wall hernia surgery with bilateral component separation surgery.

There is a large fluid collection with air bubbles as a result of infection.

Image

Fluid collection with air configurations (black arrow) and associated fistula to the abdominal wall (blue arrow).

This is an infected mesh.

Mesh ingrowth in bowel

This is an uncommon complication.

Image

A calcified mesh has migrated into

the bowel (black arrow).

Adhesions

The presence of viscera inside the hernia sac is associated with greater difficulty in dissecting it and greater risk of an iatrogenic injury compared to hernias that only contain fat.

Image

There is a midline hernia with bowel content.

There are adhesions between the bowel and the thickened skin (arrow).

In this patient there are also adhesions connecting the skin to the bowel (black arrow), but also to the bladder (blue arrow)

In this patient the hernia sac contains small bowel, large bowel and parts of the liver, stomach and pancreas.

Entero-atmospheric fistula

In this patient leakage of oral contrast is seen arrow heads and white arrow.

Treatment

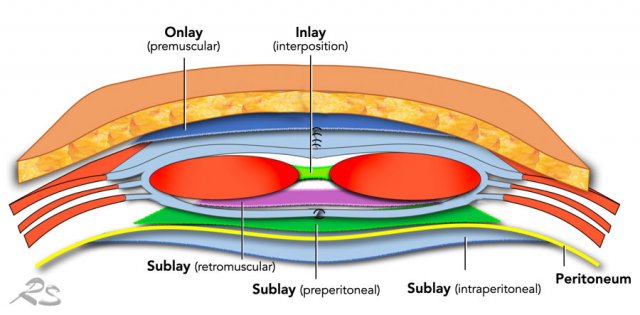

The only treatment option for abdominal wall hernia is surgery.

The aim is to close the abdominal cavity by re-approximating the fascial edges of the rectus muscles.

Attention should be paid that this is done without too much tension on the midline repair.

A mesh is almost always used to provide additional strenght and to minimize the risk of a recurrent hernia.

A mesh can be placed in many positions, but preferably located posterior to the rectus muscle.

This is called a retrorectus repair as originally described by Rives, Stoppa and Wantz.

An intra-peritoneal positioned mesh, which can be placed by open or laparoscopic repair, has a greater chance of bowel erosion and fistula formation on the long run.

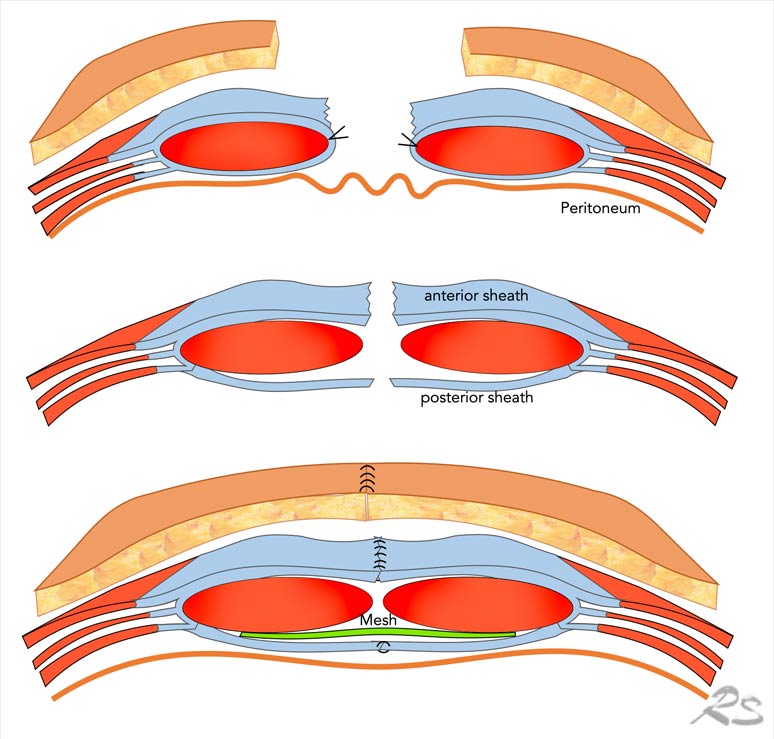

Rives-Stoppa repair

In the Rives-Stoppa repair the skin is

incised and the hernia sac is opened. The bowel is put to the side and

protected by gauze.

On both sides the posterior rectus sheath is transsected

from the rectus muscle, creating the retromuscular space. This

space is dissected laterally, just up to the linea semilunaris.

Then, the

posterior rectus sheaths from both sides are sutured together in the midline.

On this posterior layer, a mesh is positioned.

Then, the rectus muscles are

brought together, and the anterior rectus sheaths from both sides are sutured

in the midline.

Component separation

The above-described

surgical repair is quite straightforward and can be used for small and medium

sized hernias.

For large hernias or hernias with large loss of domain,

it will not be possible to medialize the rectus muscles without too much tension.

Component separation techniques (CST) are surgical strategies that facilitate

medialization of the rectus muscles, by transection one of the lateral

abdominal wall muscles from the other two.

In the Ramirez technique

(also known as the open anterior CST), after mobilization of the skin and subcutaneous tissue up to the semilunar line,

the external oblique is

dissected from the internal oblique.

It

provides about 10cm of medialization, but is associated with a high risk

of postoperative wound complications, because of the skin mobilization.

Images

- Normal lateral abdominal wall musculature.

- Ramirez abdominoplasty. Notice the position of the external oblique muscle.

Transversus Abdominus Release (oTAR)

The open posterior Components Separation or Transversus Abdominus Release (oTAR) is now the preferred treatment for large abdominal hernias.

The first step in TAR is entry into the retrorectus space from the posterior side and dissection is proceeded laterally to the linea semilunaris, the most lateral aspect of the retrorectus space.

Next the posterior rectus sheath is longitudinally divided as laterally as possible, taking care to avoid the subcostal nerves, and then the fibers of the muscular part of the Transversus Abdominus are divided with electrocautery.

By dividing the transversus abdominis muscle from the oblique internal muscles, it becomes possible to approximate both the posterior rectus sheaths.

The retromuscular space is then developed to as far as the lateral border of the psoas muscle.

The dissection is repeated on the opposite site and may be carried superiorly to the central tendon of the diaphragm, using a subxiphoid and retrosternal dissection. It may also be developed inferiorly to the retropubic space.

Then the posterior rectus sheaths are approximated to one another and a sublay mesh is placed into the retromuscular space that has been developed.

Robotic Assisted Transversus Abdominus Release (rTAR)

Most TAR procedures are currently performed by a Robot Assisted procedure. This has the advantage of a minimal invasive procedure, with less blood loss, lower risk of wound related complications, less morbidity and decreased length of stay in the hospital.

By dividing the transversus abdominis muscle from the oblique internal muscles, it will become possible to approximate both the posterior rectus sheathsRecent systematic review in Hernia.

Botox injections

Component separation technique can be very effective, but is invasive and permanent.

Botuline (Botox) injection in the muscles of the lateral abdominal wall is a

non-invasive pretreatment, and its use has become very popular in the

last couple of years. Injections 4 - 6 weeks before surgery results in thinning

and elongation of the muscles and can preclude the need to

perform CST in large hernias.

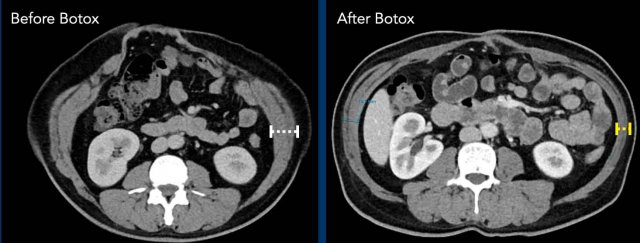

Image

Thinning and elongation of the oblique muscles after Botox injection..

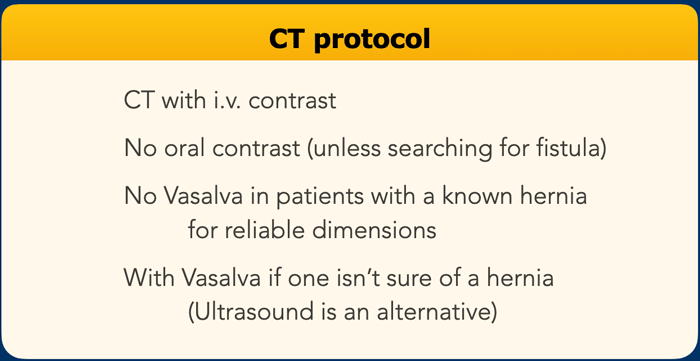

CT protocol

For primary and small hernias ultrasound imaging can suffice.

For all other type of hernias CT imaging is preferred.

I.v. contrast is not always necessary, but can be helpful in complicated cases.

Abdominal wall structured report

In the table an example of a structured report (9).