Pulsatile and non-pulsatile tinnitus

Ruud Becks, Sjoert Pegge and Anton Meijer

Department of radiology and nuclear medicine, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

This article is based on a review by Pegge et al. describing a systematic approach for the diagnostic work-up of tinnitus [1].

The differential diagnosis is related to findings on different imaging modalities.

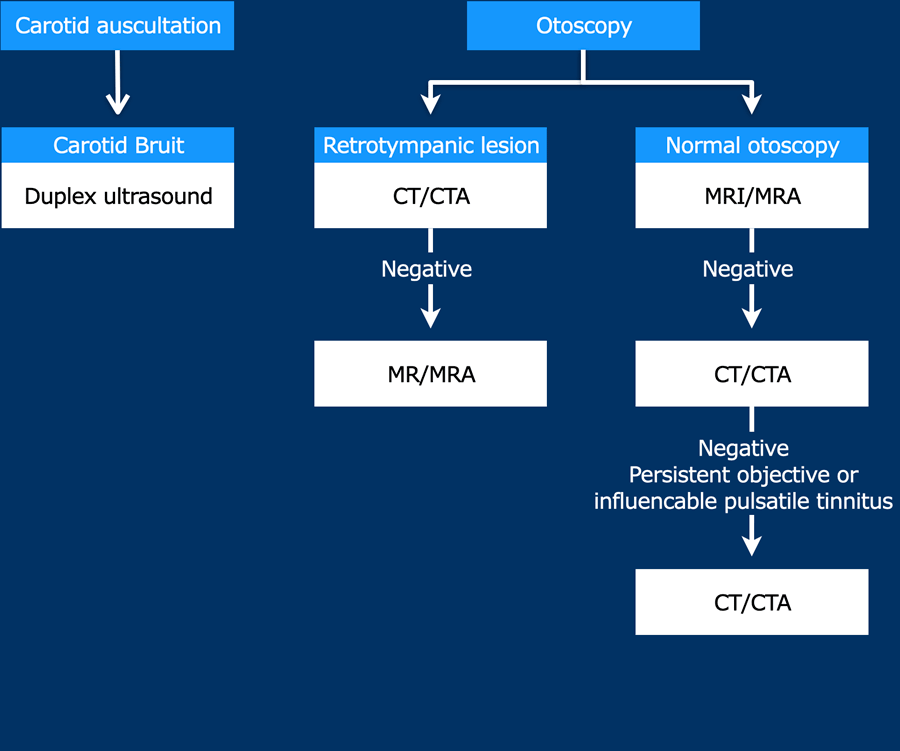

A flowchart for choosing the appropriate imaging modality in pulsatile tinnitus is provided.

Introduction and flowchart

Tinnitus is defined as an auditory perception of internal origin, and can have a significant influence on the wellbeing and performance in daily activities of affected subjects.

In pulsatile tinnitus, the auditory perception is repetitively synchronous to the patient’s heartbeat.

All other auditory perceptions are considered non-pulsatile.

Less than 10% of patients presenting with tinnitus have pulsatile tinnitus.

In about 70% of the cases with pulsatile tinnitus, an underlying cause can be identified by adequate diagnostic work-up as shown on the flow chart.

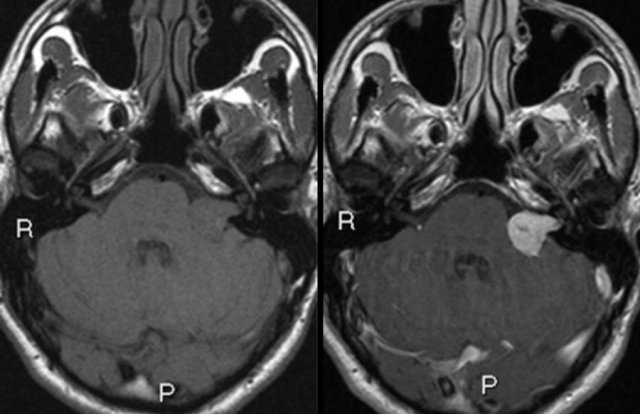

Left sided vestibular schwannoma. Axial non contrast-enhanced T1-W (left) and contrast-enhanced images (right).

Left sided vestibular schwannoma. Axial non contrast-enhanced T1-W (left) and contrast-enhanced images (right).

Non-pulsatile tinnitus

Non-pulsatile tinnitus is almost always subjective.

Different underlying conditions relate to the development of non-pulsatile tinnitus, including cerumen impaction, middle ear infection, medications, noise-induced hearing loss, presbycusis or chronic bilateral hearing loss, hemorrhage, neurodegeneration, and spontaneous intracranial hypotension [2].

MRI is only recommended in patients with unilateral (non-pulsatile) tinnitus with focal neurological abnormalities, or asymmetric hearing loss [4].

The main purpose of diagnostic imaging is to identify or rule out a lesion in the cerebellopontine angle cistern, (e.g. vestibular schwannoma).

Labyrinthine abnormalities can be identified on MRI supporting the diagnosis of Ménière’s disease [3].

Pulsatile tinnitus

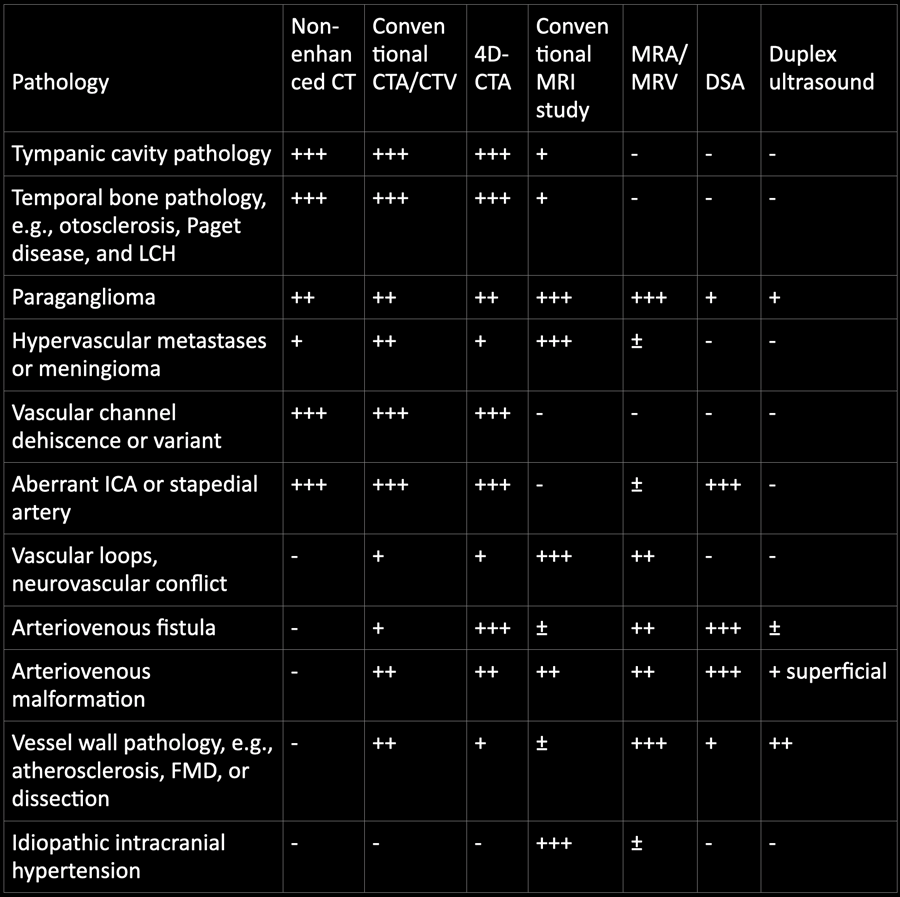

+++ Most optimal, ++ good, + moderate, ± indirect signs, – not suitable, LCH Langerhans cell histiocytosis, ICA internal carotid artery, FMD fibromuscular dysplasia

+++ Most optimal, ++ good, + moderate, ± indirect signs, – not suitable, LCH Langerhans cell histiocytosis, ICA internal carotid artery, FMD fibromuscular dysplasia

Pathology and imaging

You can click on the table for a large view.

For screening for underlying pathology and for the evaluation of a possible soft tissue mass or intracranial pathology, initial evaluation with MRI and MR angiography (MRA) is recommended with reported high diagnostic accuracy.

For the evaluation of osseous pathology of the temporal bone, a limited scanning range of thin-sliced (submillimetric) CT is sufficient.

Multi-detector CTA or CT venography (CTV) of the head and neck region can be performed for the evaluation of vascular pathology.

Dynamic CTA, also referred to as 4D-CTA, is a technique that combines the non-invasive nature of CTA with the dynamic acquisition of digital subtraction angiography (DSA).

The role of conventional angiography (DSA) in the diagnostic work-up of pulsatile tinnitus has been minimized, and should be reserved for the indication to rule out vascular pathology in case MRI/MRA and CT/(4D-)CTA have not revealed the cause of pulsatile tinnitus.

The role of duplex ultrasound in the diagnostic work-up of pulsatile tinnitus is limited, although duplex ultrasound is an effective screening tool for the evaluation of vessel wall pathology of the carotid arteries, e.g. stenosis and occlusion.

During ultrasound, manual compression can be performed to investigate the influence of compression on tinnitus.

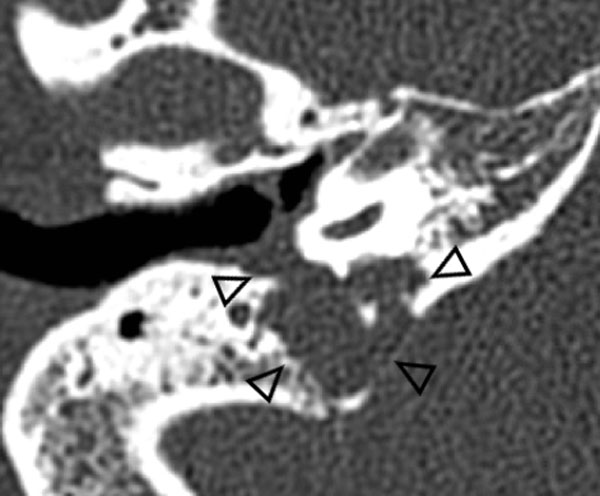

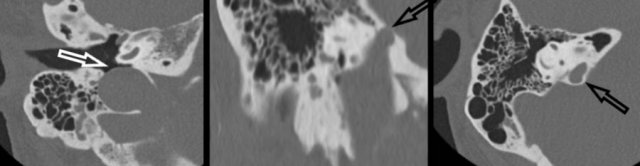

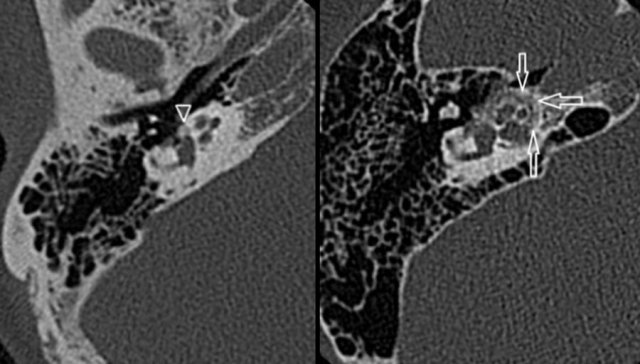

Otosclerosis: hypoattenuated bone in the region of the fissula ante fenestram in fenestral otosclerosis (left). Cochlear otosclerosis appears as a hypoattenuated halo surrounding the cochlea on CT (right).

Otosclerosis: hypoattenuated bone in the region of the fissula ante fenestram in fenestral otosclerosis (left). Cochlear otosclerosis appears as a hypoattenuated halo surrounding the cochlea on CT (right).

Temporal bone pathology

Temporal bone pathology like otosclerosis, Paget disease, and LCH can cause pulsatile tinnitus.

Otosclerosis

Is also known as otospongiosis, is an idiopathic infiltrative process of the petrous bone.

It causes both sensorineural and conductive hearing loss, and can be the cause of pulsatile tinnitus.

High-resolution, thin-sliced CT typically shows abnormal hypoattenuated bone in the region of the fissula ante fenestram in fenestral otosclerosis (left).

Cochlear otosclerosis

This appears as a hypoattenuated halo surrounding the cochlea on CT (right).

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare benign disorder of clonal histiocyte proliferation.

Clinical symptoms in LCH depend on the extent of bone and extraskeletal involvement.

Imaging typically reveals an aggressive lytic osseous lesion with associated soft tissue masses without surrounding sclerosis.

The image shows an aggressive lytic osseous lesion with soft tissue mass arising from the jugular foramen, which proved to be LCH..

Paraganglioma

Both CT and MRI can be used for the detection and evaluation of a paraganglioma.

The majority of tympanic paragangliomas are located on the promontory as a small well-defined tympanic soft tissue mass.

Usually, there is no or little surrounding bone erosion.

These small tumours are best evaluated using thin-sliced CT with a bone algorithm.

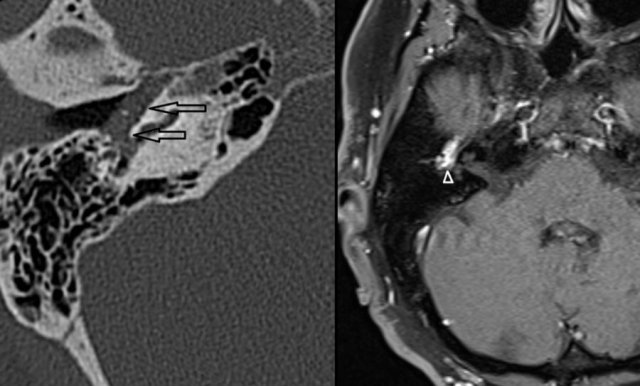

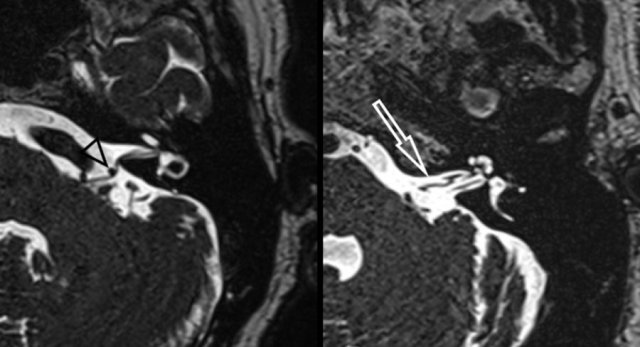

Left Axial CT shows a soft tissue mass in the middle ear (arrows).

No visible bony erosion.

Right Axial contrast enhanced T1-W with fat suppression demonstrates strong enhancement of this lesion(arrowhead).

Hypervascular metastases or meningioma

Highly vascularized bone lesions, like osseous hemangioma, basal meningioma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, or bone metastases, have been described as possible causes of pulsatile tinnitus.

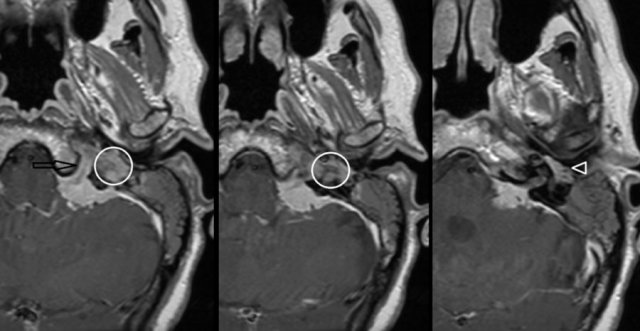

On the left a meningioma on MRI.

Axial contrast-enhanced T1-W images.

Enhancing mass located in the left cerebellar-pontine angle with extension into hypoglossal canal (arrow), jugular plate (encircled), and the middle ear (arrowhead).

Vascular channel dehiscence or variant

Venous tinnitus is heard as a continuous murmur that exaggerates in systole.

There seems to be an association with congenital variants such as a high riding, enlarged, or diverticulum of the jugular bulb, which can be best depicted on thin-sliced high-resolution CT.

Prevalence of sigmoid sinus diverticulum and dehiscence has been reported to be significantly higher in pulsatile tinnitus than in the general population.

Aberrant course of ICA or stapedial artery

An aberrant course of the internal carotid artery and persistence of the stapedial artery are congenital variants that need to be recognized on imaging studies.

An aberrant course of the internal carotid artery in the middle ear may mimic a soft tissue mass or paraganglioma at otoscopy.

On the left an Aberrant course of the internal carotid artery (arrow) and persistence of the stapedial artery (arrowhead) on thin-sliced CT.

Note the absence of the foramen spinosum (encircled).

Vascular loops, neurovascular conflict

Vascular loops and elongated arteries are occasionally described as a possible cause of pulsatile tinnitus.

Considering the presence of these vascular loops and elongations also in asymptomatic patients, other possible causes of pulsatile tinnitus need to be ruled out in those subjects.

Heavy T2 weighted CISS images on the left demonstrates a neurovascular conflict of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery with compression and displacement of the facial nerve and vestibulocochlear nerve (left image, black arrowhead).

The right image shows a grade 3 (>50%) vascular loop of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery within the left internal acoustic canal (white arrow).

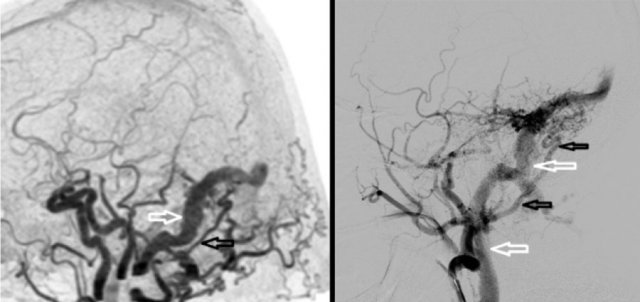

AVF: abnormal early contrast filling of the sigmoid sinus (left), venous drainage of the sigmoid sinus into the jugular vein (right)

AVF: abnormal early contrast filling of the sigmoid sinus (left), venous drainage of the sigmoid sinus into the jugular vein (right)

Arteriovenous fistula (AVF)

An AVF is an, usually acquired, abnormal connection between an artery and a vein without an intervening nidus.

Located along the dura or within a dural sinus, these are called dural AVF.

Dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) located in the right sigmoid sinus as identified by 4D-CTA and DSA.

Left 4D-CTA lateral subtracted MIP demonstrating abnormal early contrast filling of the sigmoid sinus (white arrow) consistent with dAVF.

Hypertrophic occipital artery identified as arterial feeder (black arrow).

Right DSA, selective contrast injection of the external carotid artery showing a hypertrophic tortuous occipital artery (black arrows).

Venous drainage of the sigmoid sinus into the jugular vein (white arrows).

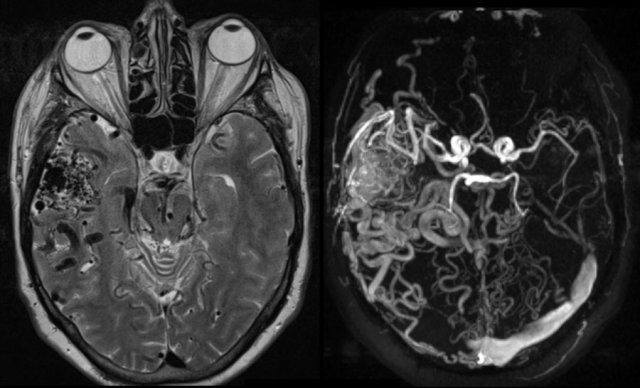

Arteriovenous malformation (AVM)

An AVM located in the head and neck region can be the cause of pulsatile tinnitus.

Typically, an AVM develops in adolescence or young adulthood but can remain occult for a long period.

T2-W (left) and phase-contrast MRA (right) demonstrating intracranial arteriovenous malformation (AVM) located in the right temporal fossa.

Vessel wall pathology

Vessel wall pathology like atherosclerosis, FMD or dissection can be a cause of pulsatile tinnitus.

In the elderly population, atherosclerotic disease of the carotid or vertebral arteries is thought to be the most common cause of pulsatile tinnitus.

In a significant stenosed or occluded artery, increased vascular flow on the contralateral side could lead to pulsatile tinnitus as a symptom.

Fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) is a segmental nonatheromatous, non-inflammatory vascular disease of unknown etiology.

Often it is a disease of the young leading to vascular stenosis and cerebral ischemia.

On the left a classical imaging appearance of FMD the so-called “string of beads” pattern on MIP CTA and DSA (black arrows).

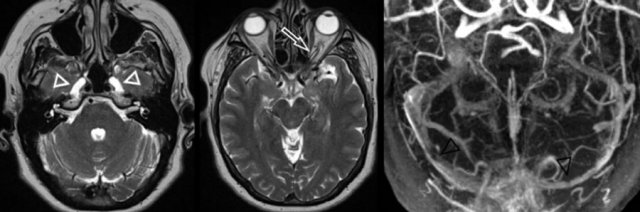

Intracranial hypertension with enlarged Meckel cave (left image, white arrowheads), prominent subarachnoid space around the optic nerve (middle image, white arrow) and bilateral venous sinus stenosis (right image, black arrowheads)

Intracranial hypertension with enlarged Meckel cave (left image, white arrowheads), prominent subarachnoid space around the optic nerve (middle image, white arrow) and bilateral venous sinus stenosis (right image, black arrowheads)

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), which predominantly affects young obese women, may cause pulsatile tinnitus, although IIH is primarily characterized by symptoms of headache and blurred vision due to increased cerebrospinal fluid pressure.

The exact pathophysiology of IIH is unknown but can develop in patients with a history of dural sinus thrombosis.

Dural sinus stenosis or compression can also be observed in IHH.

It is therefore advised to perform MRV or CTV in a patient with pulsatile tinnitus and suspicion of IIH.

On the left a typical case of intracranial hypertension with enlarged Meckel cave (left image, white arrowheads), prominent subarachnoid space around the optic nerve (middle image, white arrow) and bilateral venous sinus stenosis (right image, black arrowheads).