Imaging findings in TB

Rolando Reyna¹, Frank M. Smithuis²and Robin Smithuis³

¹Hospital Santo Tomás in Panama, ²Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit and ³Alrijne hospital in Leiden, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

Almost all patients with active TB will have pulmonary abnormalities.

Portable digital chest X-ray machines make it possible to screen patients even in remote areas.

This makes the chest X-ray the most sensitive tool to detect TB.

Unfortunately on a chest X-ray TB can

look like many other conditions, which reduces the specificity and additional

lab-tests are often necessary to confirm the diagnosis of active TB.

In this article we will focus on chest X-ray abnormalities that may indicate active TB disease.

Introduction

Primary and Post-primary TB

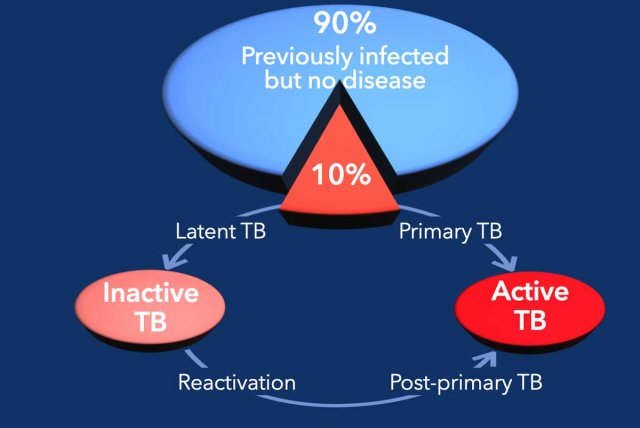

About two billion people worldwide have been infected with

TB.

90% of the infected persons will never develop active disease (many will

self-clear the infection) and only about 10% will develop TB-disease.

In about 5% of infected persons primary TB will develop within months to 2

years after the infection.

In another 5% post-primary TB will develop later in life as a result of

reactivation of latent infection.

Latent TB means that after the

primary infection with subsequent granuloma formation and decrease in the

number of bacilli, some bacilli remain viable but dormant for years.

Latent TB is generally an asymptomatic, radiologically undetected process.

However if the bacilli overcome the constraints of the immune system and

multiply, then there is progression to active TB.

The risk for progression of latent TB to active TB is greatest in patients with

HIV.

Other risk factors include diabetes, malnutrition, renal failure, malignancies

and immunosuppressive therapy like steroids and anti-TNF drugs.

The old dogma

In the article "Radiographic Appearance of Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Dogma Disproved" Anna Rozenstein and colleagues clearly demonstrated, that generations of physicians have wrongly been taught that primary TB can be differentiated from post-primary or reactivation TB on the basis of radiographic appearance.

This was thought to be helpful in clinical management, because in a patient with primary TB you had to find the person who had infected your patient in order to prevent epidemic spread, while in post-primary TB you only had to treat your patient and protect the people around this patient.

TB and immune status

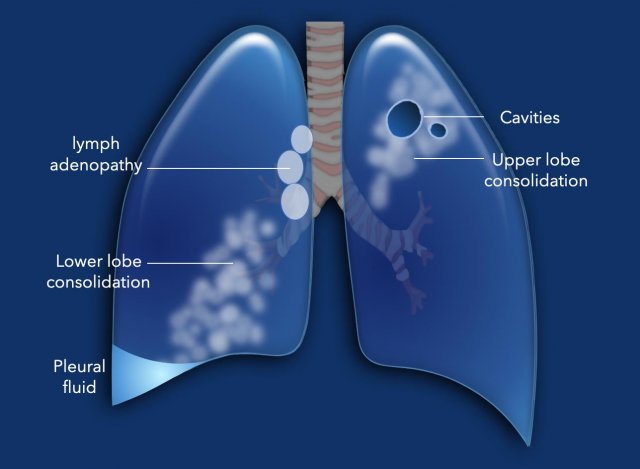

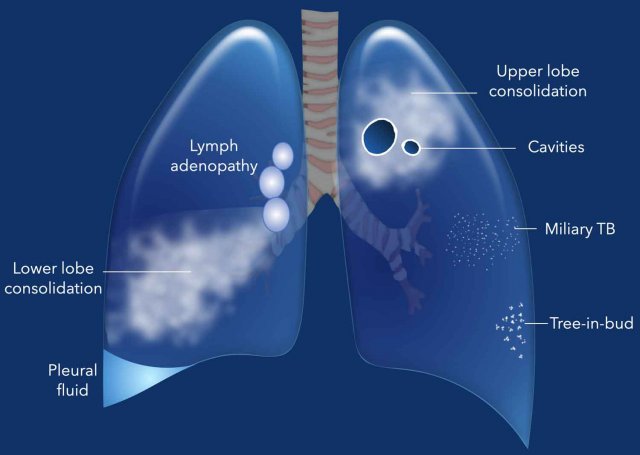

Now we know that the way TB presents on chest X-rays, mainly depends on the immune status of the patient.

In young children the immune response is less mature than in adults and TB disease more often presents with adenopathy, effusion and lower lung zone disease (figure right lung). This was thought to be primary TB.

In adults with a competent immune system, TB more often presents with upper lobe consolidation and cavitation (figure left lung), which was wrongly diagnosed as post-primary or reactivation TB.

This also explains why in HIV-patients with a low CD-4 count lymphadenopathy, lower lobe consolidation and pleural fluid is more common, while in HIV-patients with a normal CD-4 count upper lobe cavitation is more common.

Inactive and Active TB

Radiologist’s Role in TB Evaluation

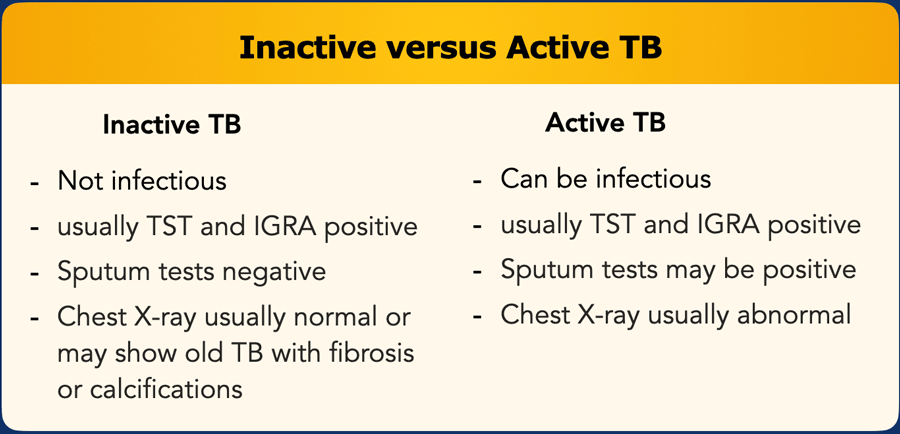

The radiologist must identify and distinguish between active and inactive TB.

Chest X-ray Findings

Latent or old TB often presents with normal chest X-rays, though calcifications, scarring, or volume loss may be visible.

Active TB presents with consolidation, lymph adenopathy, cavities and pleural fluid.

Laboratory Tests

Tuberculin skin test (TST) or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) are typically positive following TB exposure, regardless of active or latent infection.

These tests may also be positive in individuals who previously cleared the infection and are no longer infected, subsequently these tests cannot differentiate between active and inactive TB..

Bacterial tests frequently yield no result, especially in children (due to lack of sputum) or when sputum quality is poor (e.g., not from the lungs).

This means that the chest X-ray is an important tool for triaging and screening for pulmonary TB, selecting individuals for bacteriological examination and for aiding the diagnosis when pulmonary TB cannot be confirmed bacteriologically.

Active TB

This illustration is a summary of the various findings in active TB.

- Lymphadenopathy without a lung nodule is a common finding in children and has a high specificity for TB.

- Consolidation caused by TB is indistinguishable from bacterial pneumonia. Chronic consolidation, lymphadenopathy and the lack of response to conventional antibiotics are in favor of the diagnosis of TB.

- Pleural effusion is a common manifestation of active TB and especially seen in children and in HIV-patients with a low CD-4 count.

- Cavitation has a high specificity for TB.

- Miliary disease is the result of hematogenous spread to the lungs and other organs.

- Tree-in-bud appearance is typical for active endobronchial spread of infection. It was once thought to be specific for TB, but can be seen in other bacterial infections.

Lymphadenopathy

Lymphadenopathy without a lung nodule is a common finding in children and has a high specificity for TB.

Lymphadenopathy in combination with a small lung nodule, also called primary focus, is called a primary complex (Ghon complex).

This is rather uncommon.

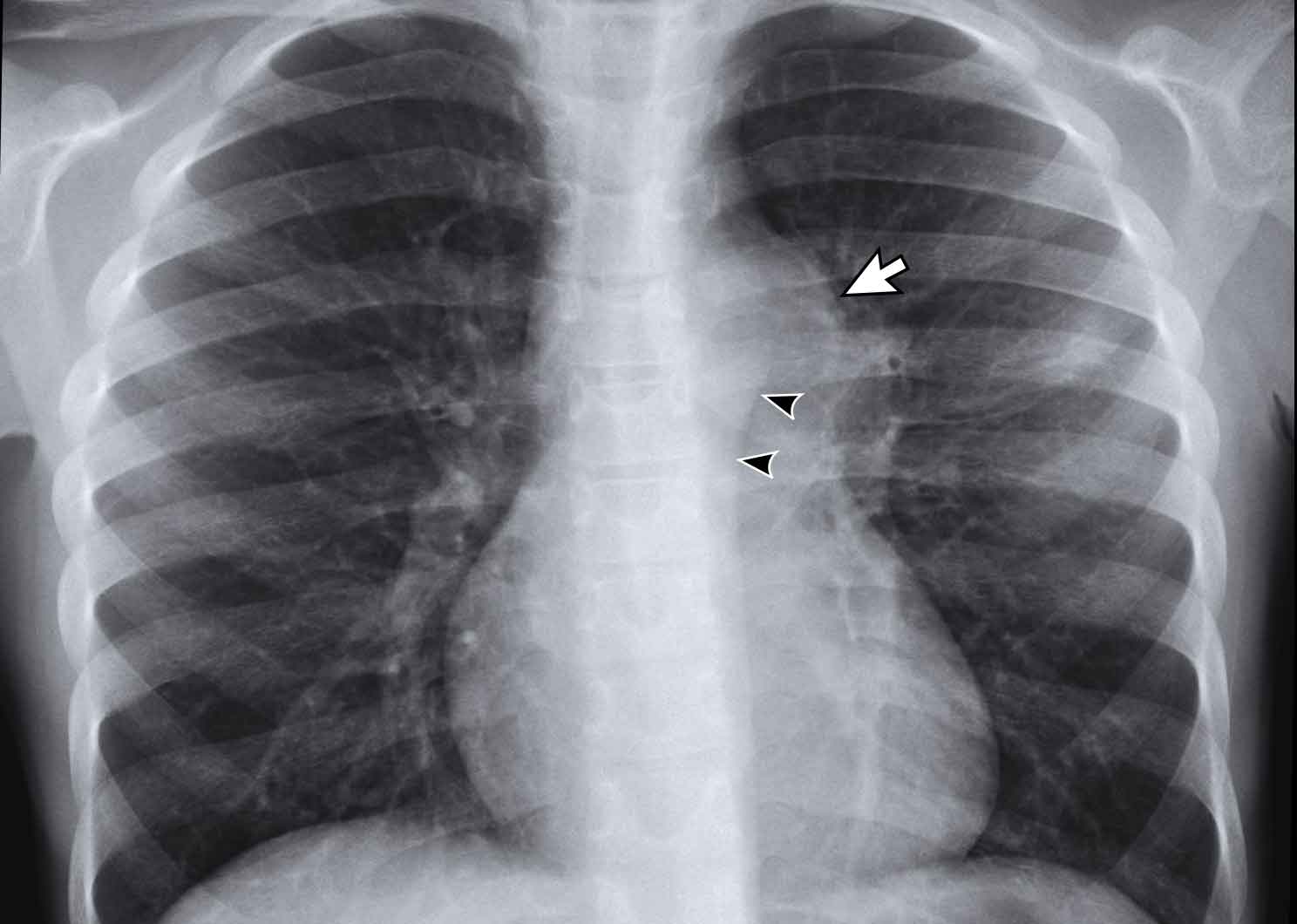

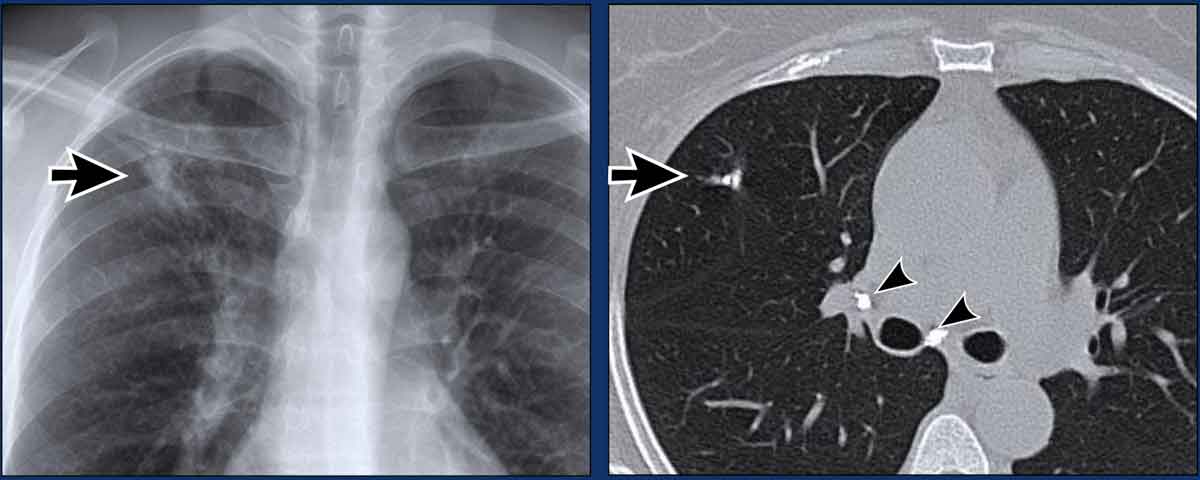

Image

There is a double contour on the left caused by enlarged lymph nodes (arrow) and the aorta (arrowheads).

Continue with the CT....

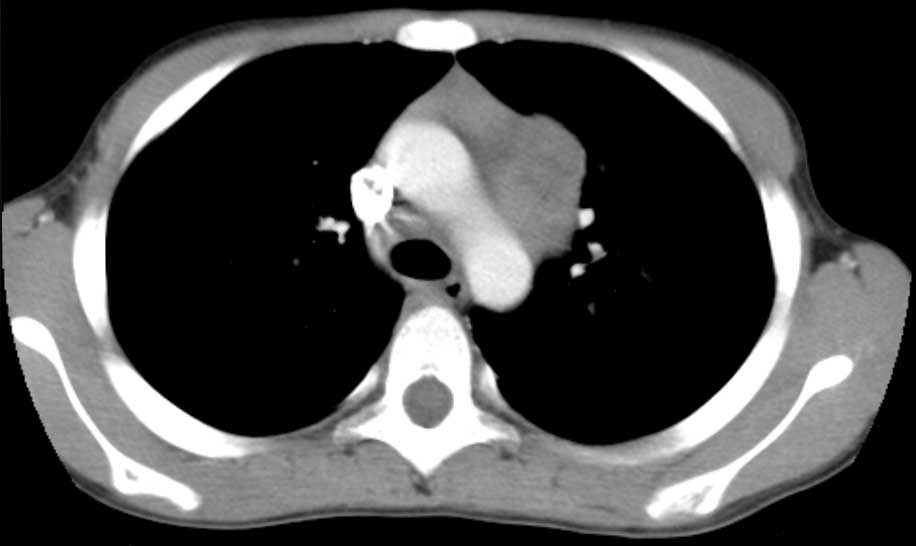

Image

Multiple enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes in a child with active TB.

In children less than 2 years of age, lobar or segmental atelectasis is sometimes seen, typically involving the anterior segment of an upper lobe or the medial segment of the middle lobe, usually a result of adjacent lymphadenopathy and compressive effects.

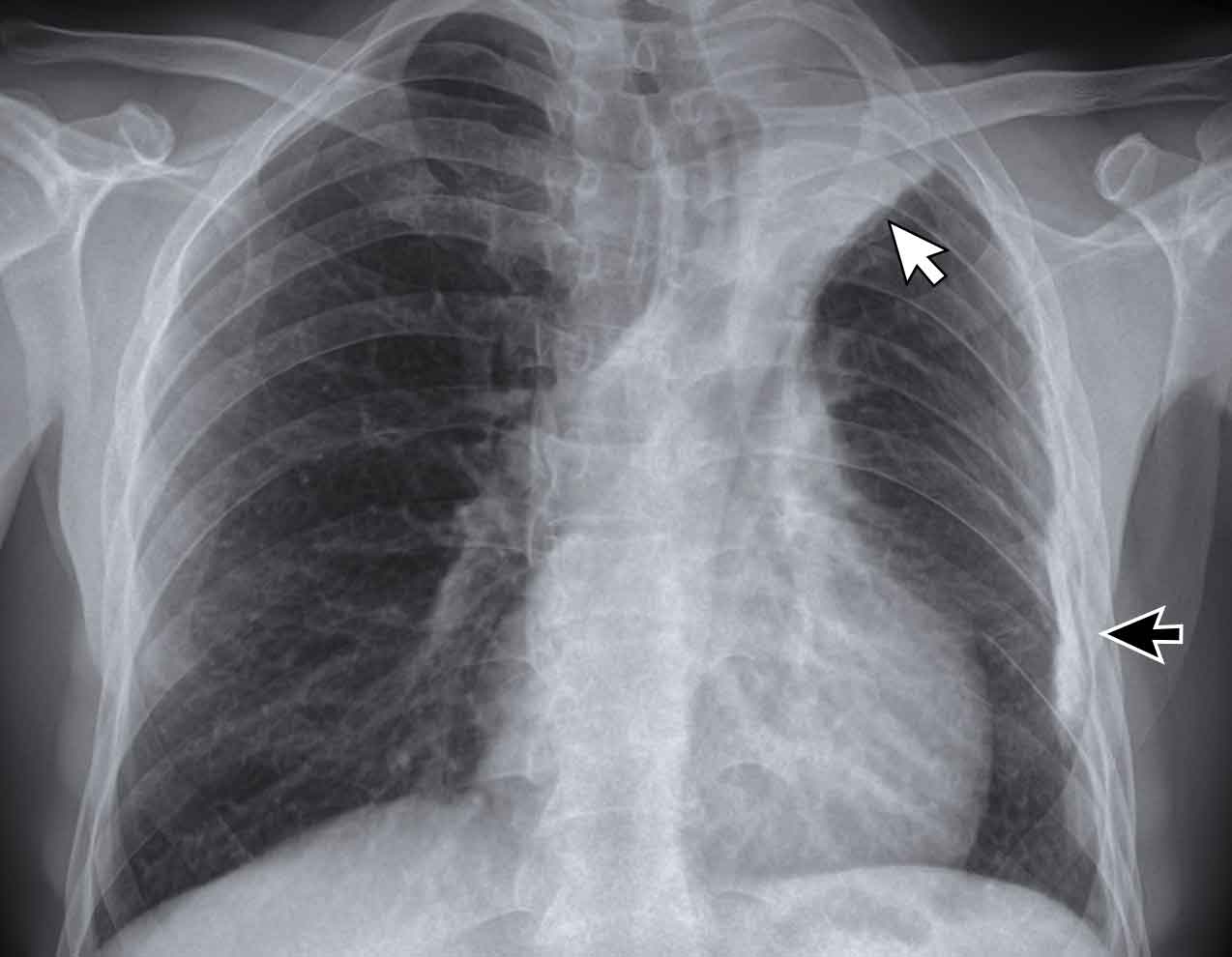

Pleural fluid

Pleural effusion is a common manifestation of active TB and especially seen in children and in HIV-patients with a low CD-4 count.

The fluid is a lymphocytic, protein-rich exsudate as a result of a hypersensitivity reaction to a sub-pleural focus.

These effusions are usually simple and large and are most commonly seen in older children and adolescents.

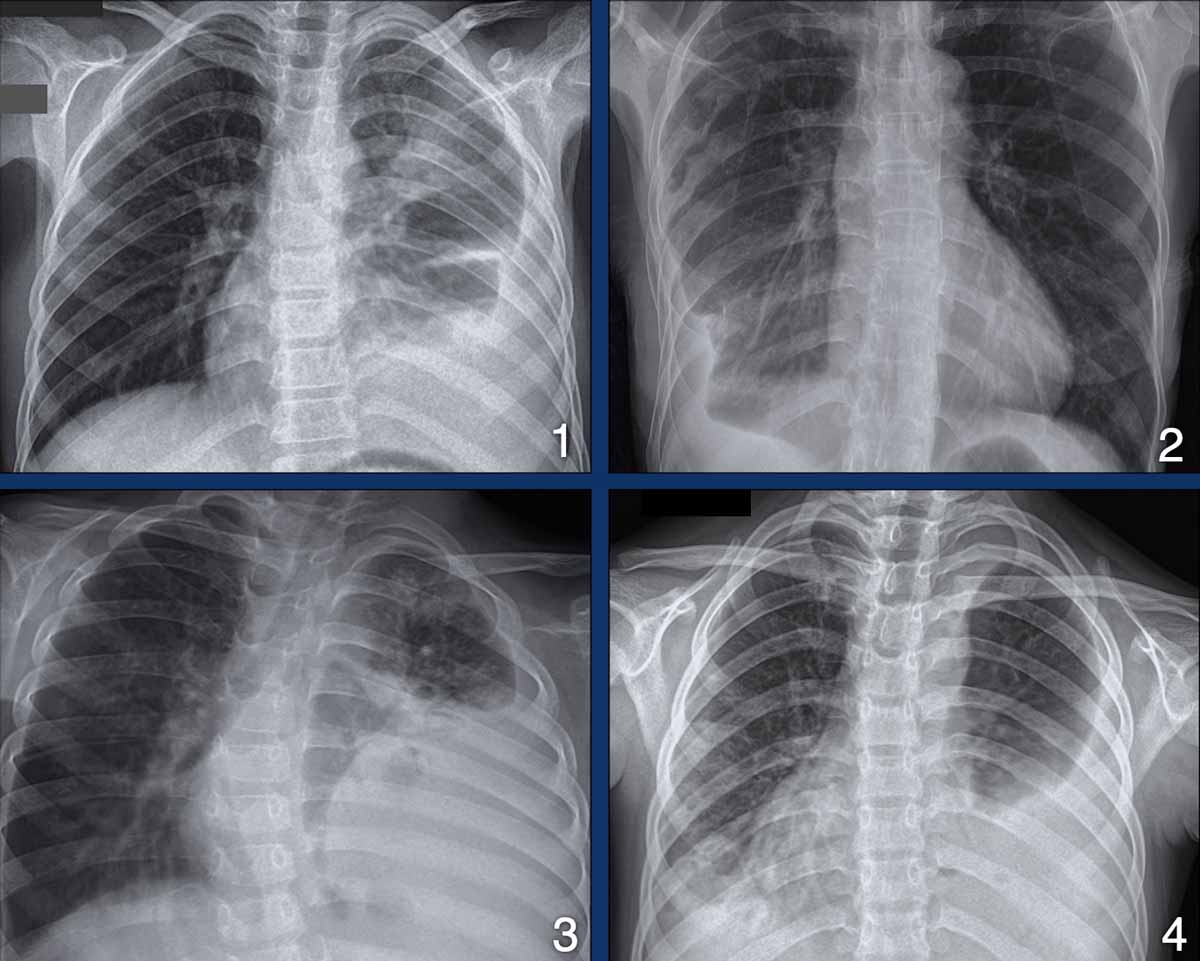

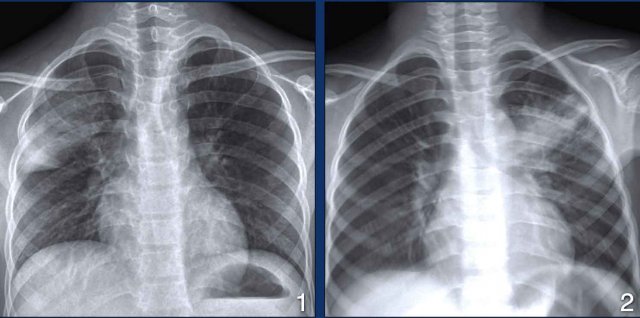

The images show four examples of pleural fluid in patients with TB.

Images

- A 12-year old boy with lethargy, weight loss and chronic cough.

There is left upper lobe consolidation and a large amount of pleural fluid. - Unilateral pleural effusion. Notice also rib abnormalities. These may be a result of TB.

- Large amount of pleural fluid resulting in mediastinal shift and compression of the left lung in a 6-year old boy.

- Large amount of pleural fluid both caudally and cranially of the compressed left lung.

DD of unilateral pleural fluid

Mostly seen in infectious diseases and in malignancy like lung cancer, breast cancer and mesothelioma.

Other causes are pulmonary emboli, connective tissue disease and heart failure (usually bilateral, but can be unilateral).

Consolidation

Parenchymal disease manifests as dense, homogeneous consolidation in any lobe and is often indistinguishable from bacterial pneumonia.

It is a common finding, but with a low specificity.

Chronic consolidation, lymphadenopathy and the lack of response to conventional antibiotics are in favor of the diagnosis of TB.

Images

- 12-year old with TB. There is right upper lobe consolidation. No lymphadenopathy. No pleural fluid.

- 6-year old with TB. Left upper lobe consolidation. Haziness due to movement artefacts.

DD Consolidation

The differential diagnosis of consolidation is extensive and discussed here.

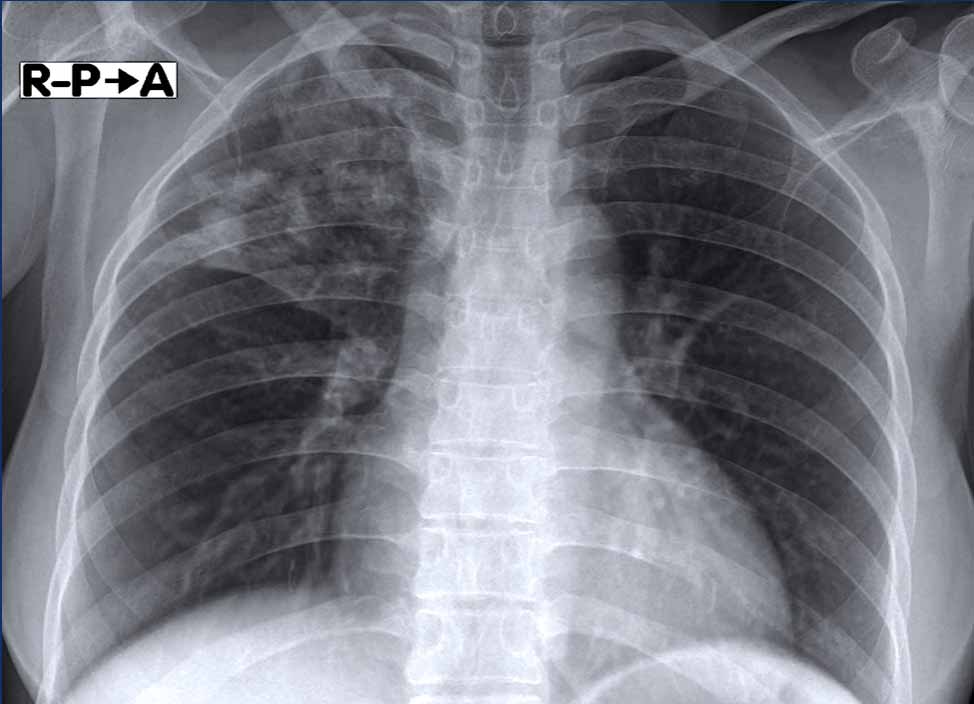

This image is of a 36-year old female who complains of chest pain, coughing and has fever.

Image

Dense consolidations in the right upper lobe with some volume loss.

Lab tests of sputum were positive for TB.

Cavitation

Cavitation occurs in about half of the patients with active TB.

These patients have a high bacterial load and are highly contagious.

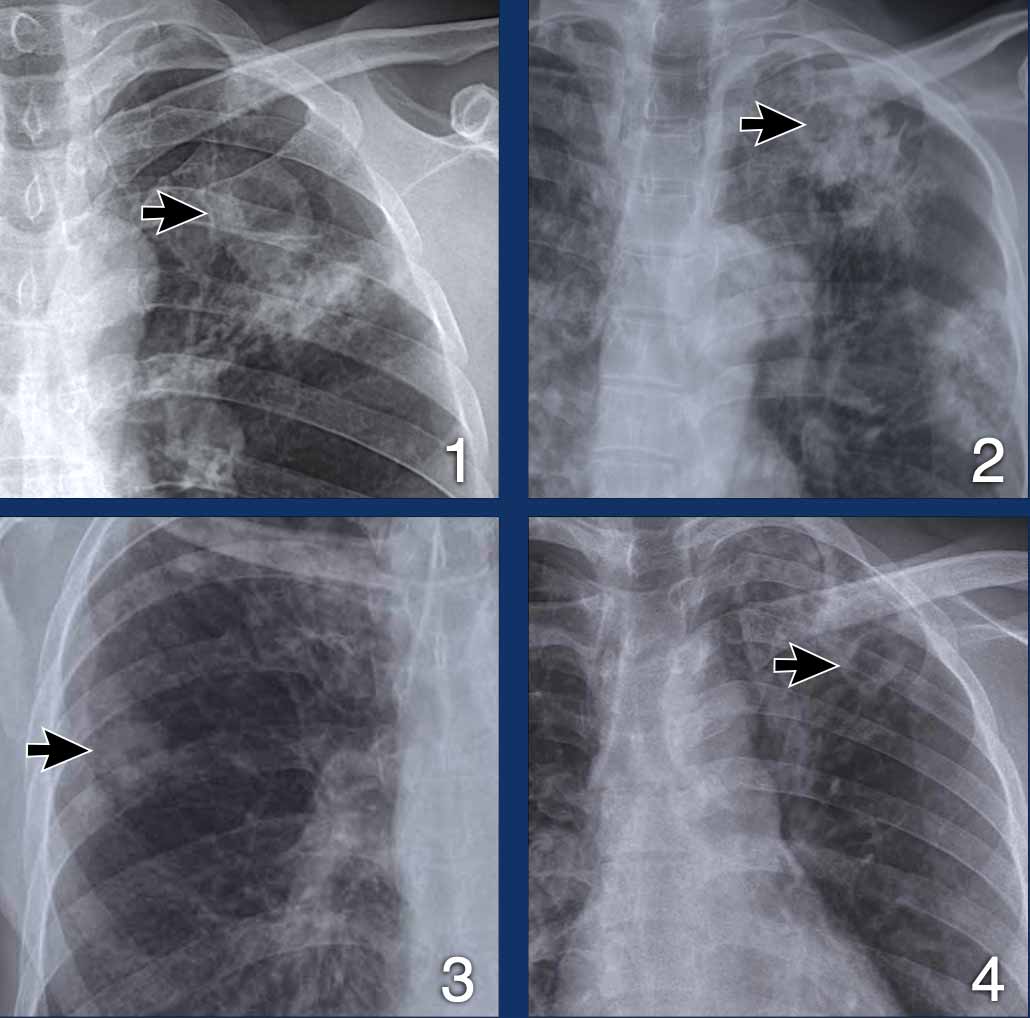

Images

- Upper lobe consolidation and cavitation.

- Dense consolidation with subtle cavitation (arrow).

- Small thick-walled cavitation.

- Left upper lobe cavitation.

All these patients had lab-proven TB.

DD Cavitation

Cavitation is also seen in virulent pyogenic infections with abscess formation.

These patients are usually very ill.

Cavitating lungcancer is an important differential.

In granulomatous infection like TB, cavities may form, but these patients are usually not that ill.

Other granulomatous diseases that may form cavities are Rheumatoid arthritis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener).

Cavitation is not seen in viral pneumonia, mycoplasma and rarely in streptococcus pneumoniae.

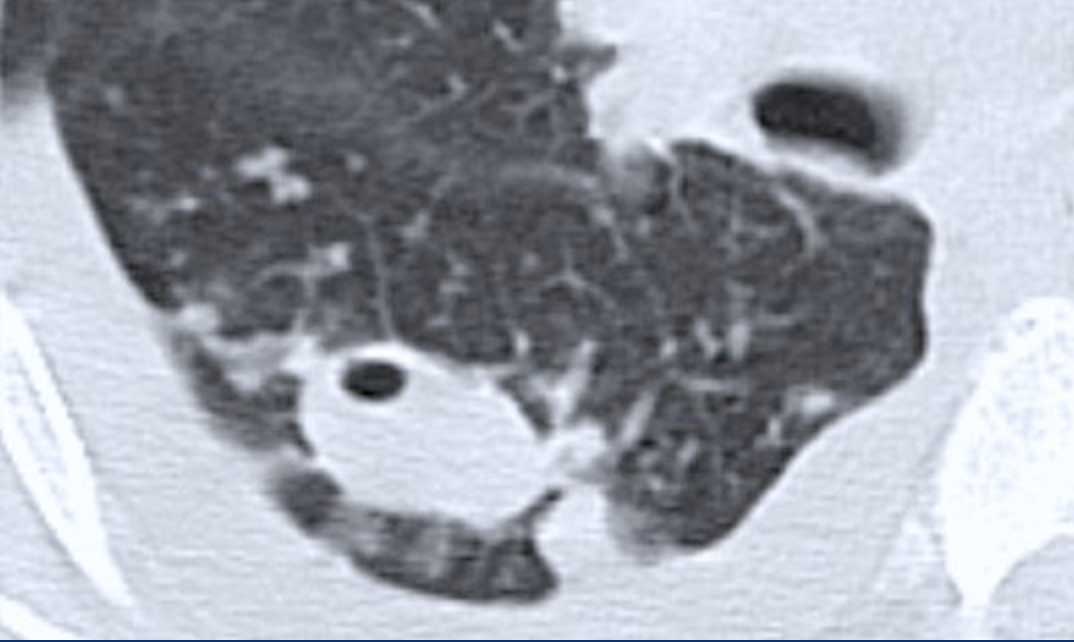

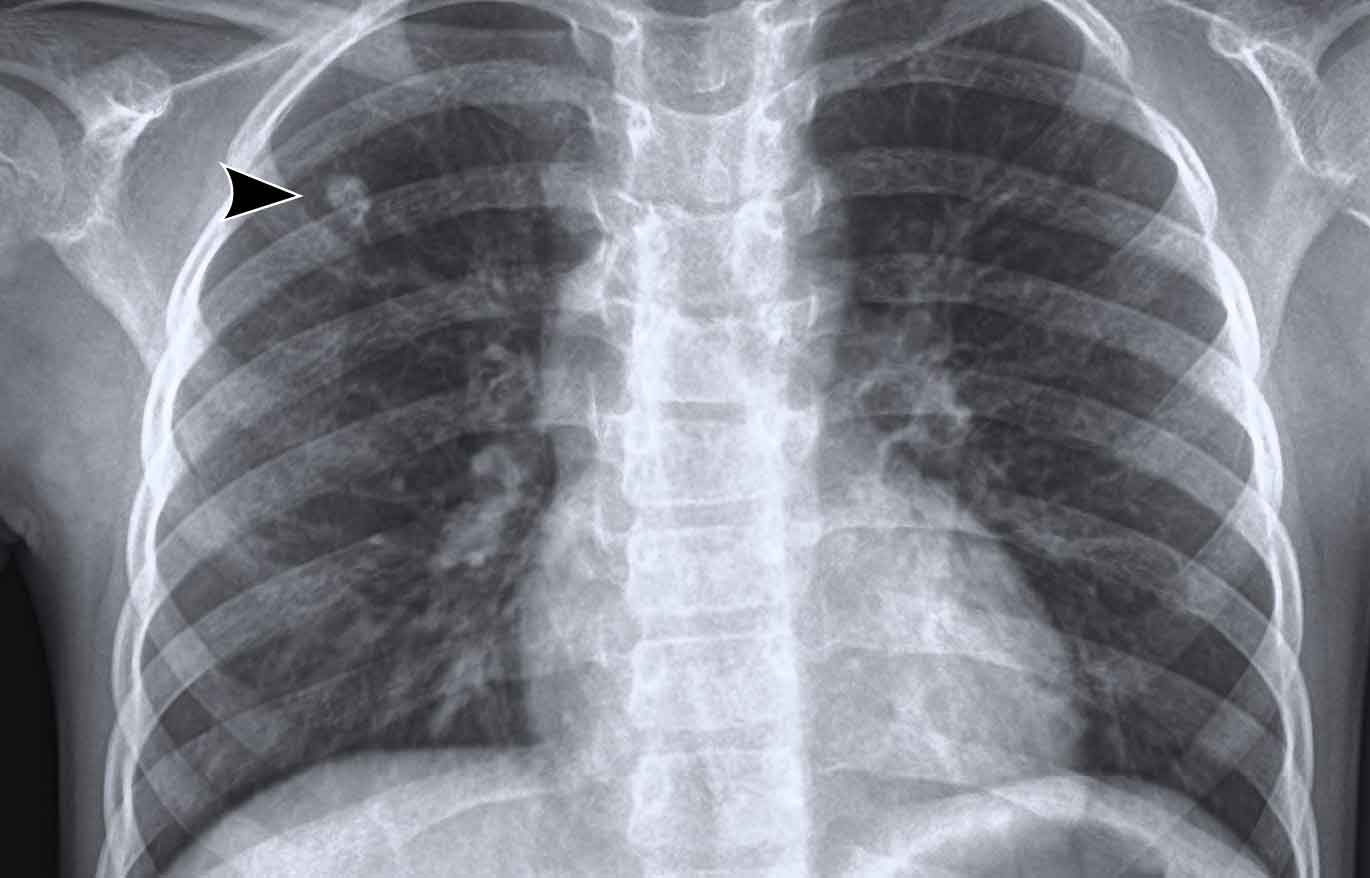

This image is of a sixty year old male who had a mass on a chest X-ray.

A CT-guided biopsy was performed because there was suspicion of lungcancer.

Image

There is a mass with cavitation in the right lower lobe.

Notice also the tree-in-bud densities surrounding the mass.

TB was biopsy proven.

Tree-in-bud pattern

Tree-in-bud appearance is typical for active endobronchial spread of infection.

This pattern can be difficult to appreciate on a chest x-ray, but is well seen on a chest CT.

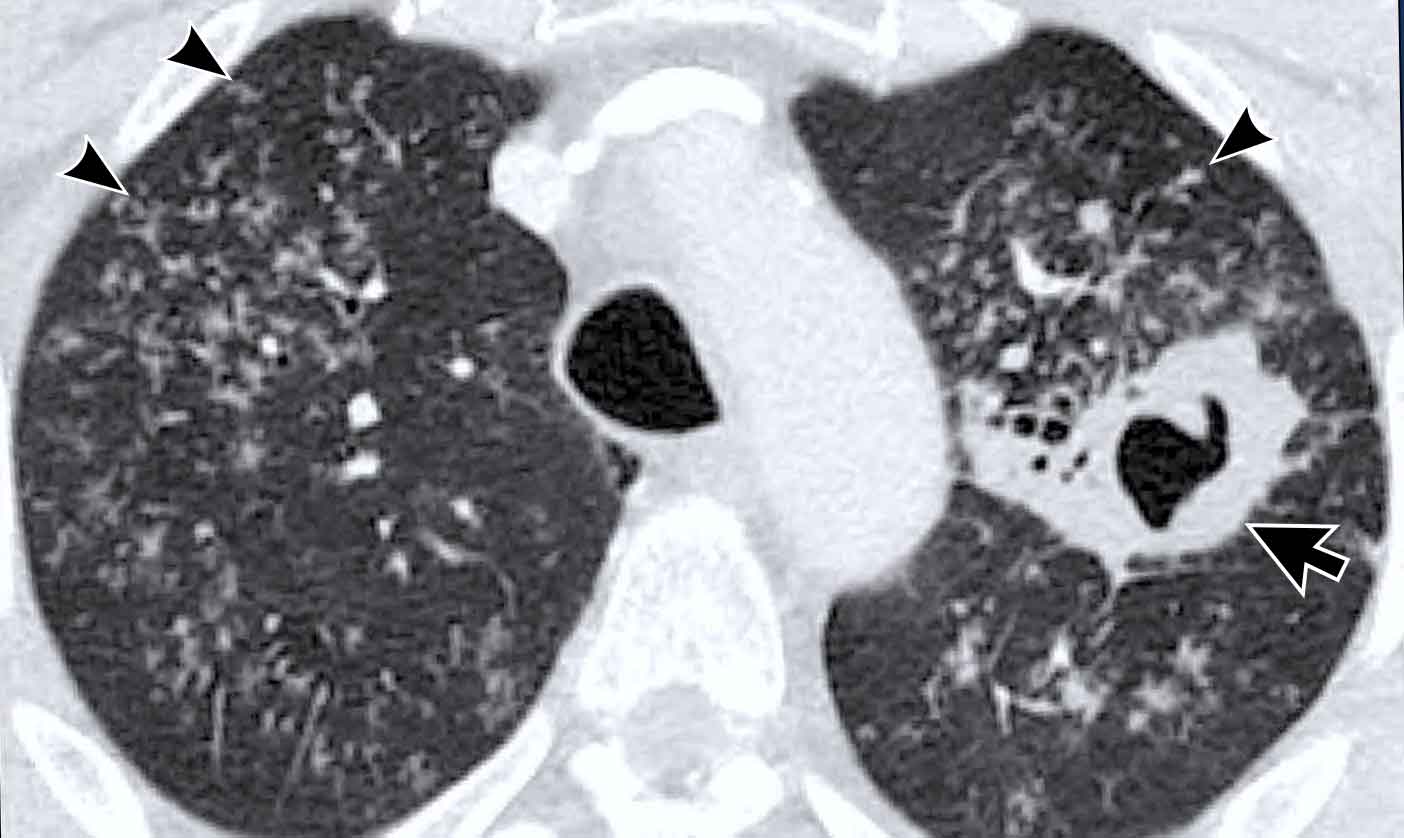

Image

Bilateral tree-in-bud nodules (arrowheads) and a cavitation in the left upper lobe.

This combination of findings is very specific for active TB.

Differential Diagnosis

- Endobronchial spread of infection: TB, MAC or any bacterial bronchopneumonia.

- Airway disease associated with infection like cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis.

- Aspiration.

- Less often an airway disease associated primarily with mucus retention like allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis or asthma.

Same image as shown before.

Lab test for TB were negative.

Image

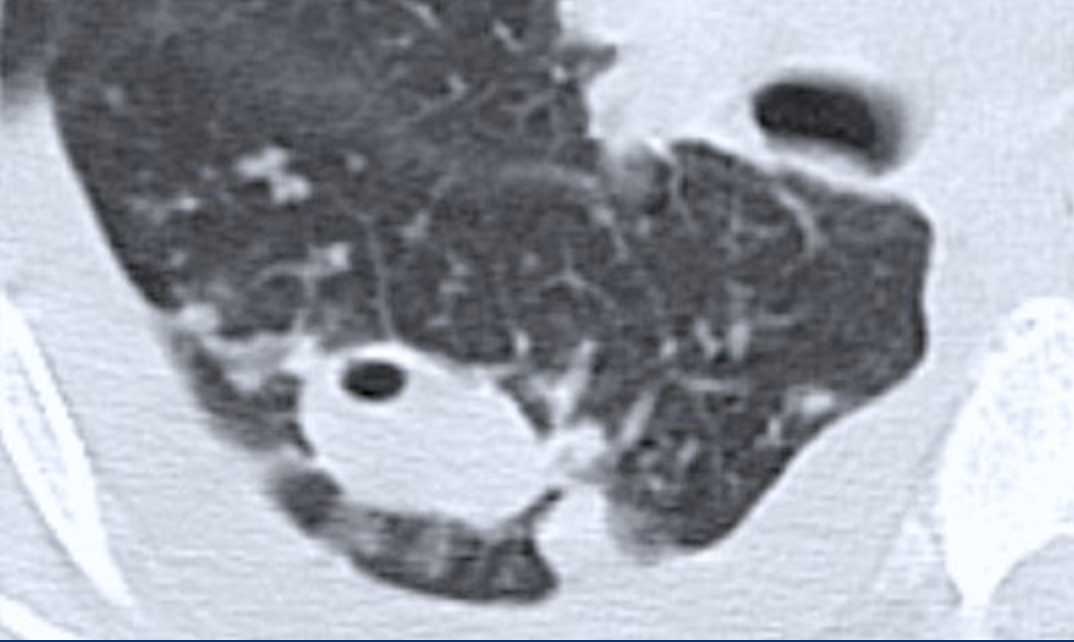

There is a mass with cavitation in the right lower lobe.

Notice also subtle tree-in-bud densities surrounding the mass.

Continue with the biopsy...

Image

Biopsy needle is seen.

The tree-in-bud pattern is even better seen than on the prior CT.

This was biopsy proven TB.

The combination of cavitation and tree-in-bud pattern means that we are dealing with severe active TB.

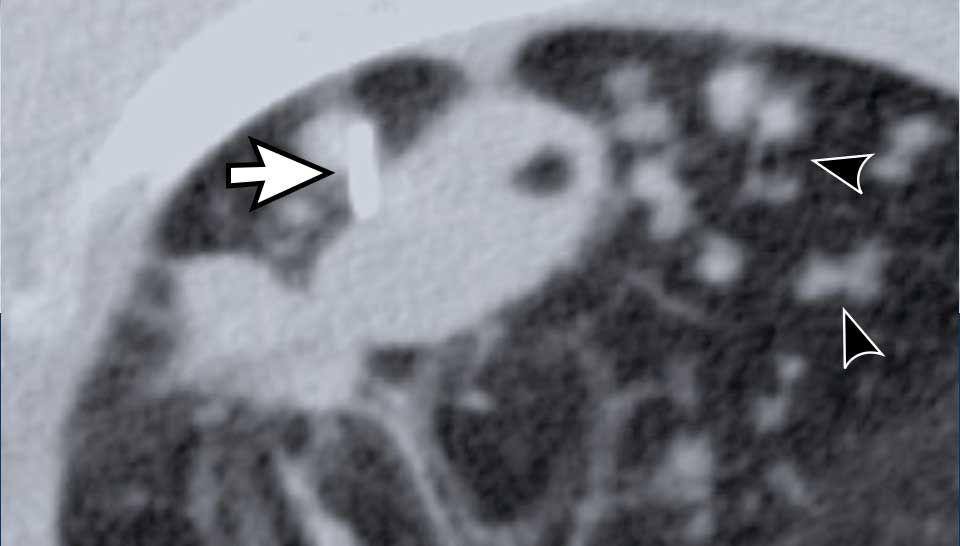

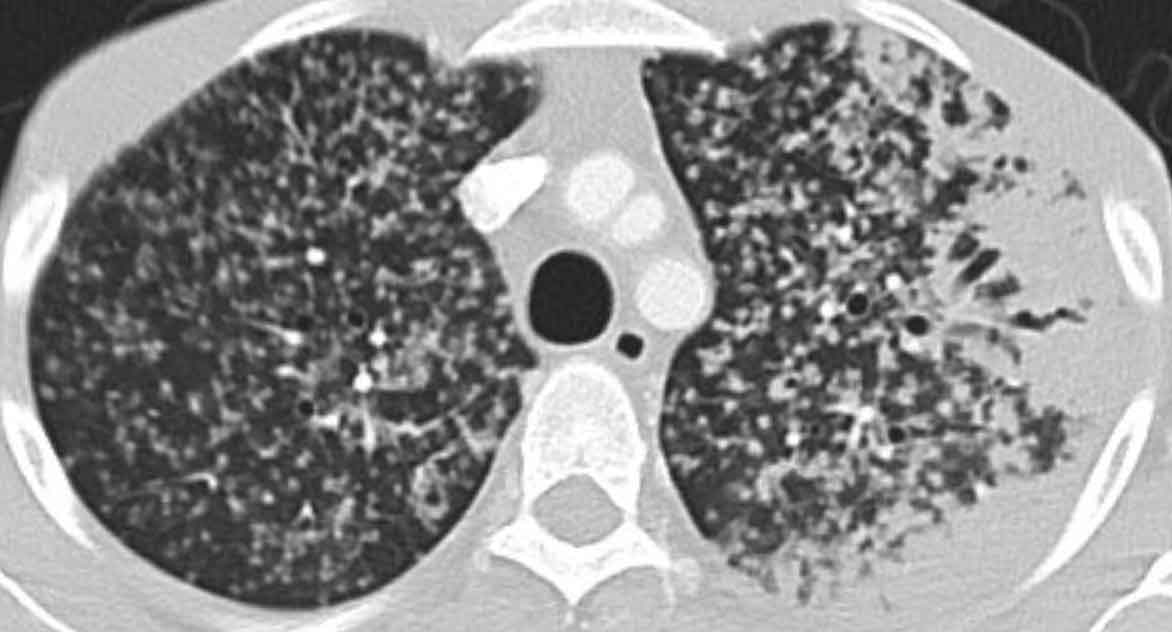

Miliary disease

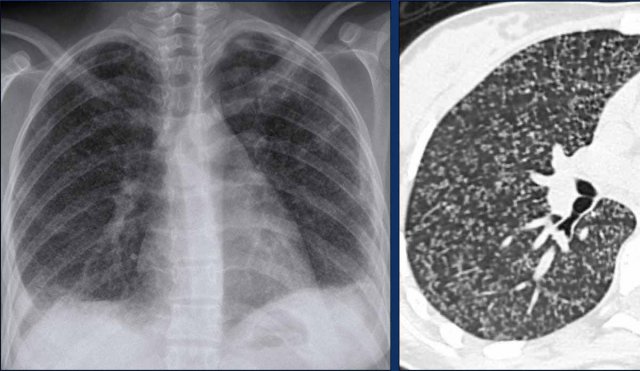

This is the result of hematogenous spread of TB to other organs.

In the lung it manifests as multiple 2-3 mm nodules with a random distribution.

These nodule can be difficult to appreciate on a chest x-ray, but are well seen on a chest CT.

It is an uncommon finding, but with a high specificity.

Differential Diagnosis

- Metastases of medullary thyroid carcinoma, chorioncarcinoma and melanoma.

Another TB patient with miliary disease.

There is also peripheral consolidation in the left lung.

Ghon focus

TB bacilli can settle in the alveoli and proliferate to form a Ghon focus, named after the Austrian pathologist Arthur Ghon.

A Ghon focus is usually not radiologically visible unless when it calcifies, which occurs in about 15% of cases.

The bacilli can spread from the Ghon focus to the nearest mediastinal lymph nodes.

A Ghon complex is a Ghon focus with ipsilateral mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

Inactive TB

Apical fibrosis

Apical fibrotic lesions or scars, also known as old healed tuberculosis, are a common finding on chest X-rays in areas with endemic TB.

These persons do not have active TB and are not infectious.

Images

Scarring especially in the upper lobes sometimes with volume loss.

This image is of a 28-year old male with a history of TB.

There is scarring in both upper lobes.

No sign of active TB.

Calcifications

Images

Calcification in the lung and calcified lymph nodes.

This is also known as a Ranke's complex.

Image

Small calcified lung nodule in a 9-year old girl, who lives in an area with endemic TB..

This is probably the result of a prior TB infection.

No sign of active TB.

Image

Collaps of the left upper lobe with mediastinal shift in a person who had TB many years ago.

Notice also the pleural calcifications (black arrow).

WHO and TB

A mobile medical team from Medical Action Myanmar, conducting active screening for TB in remote communities

A mobile medical team from Medical Action Myanmar, conducting active screening for TB in remote communities

For many years, the WHO has recommended the chest x-ray (CXR) as a diagnostic tool to be used at the end of diagnostic algorithms as a complementary part of the clinical diagnosis of bacteriologically negative TB.

Using CXR to diagnose TB was thought to be problematic, given that CXR has low specificity with significant interobserver variation combined with poor access to high-quality radiography equipment and expert interpretation.

Recently, however, CXR has been promoted as a useful tool that can be placed early in screening and triaging algorithms.

An important reason for rethinking the role of CXR is that numerous national TB prevalence surveys have demonstrated that CXR is the most sensitive screening tool for pulmonary TB and that a significant proportion of people with TB are asymptomatic early in the course of the disease.

The increased availability of digital radiography with its lower costs and portable systems for field use, better image quality and use for telemedicine and AI technology, has contributed to CXR becoming an increasingly accepted part of programmatic approaches to TB care and prevention.

Charity

All the profits of the Radiology Assistant go to Medical Action Myanmar which is run by Dr. Nini Tun and Dr. Frank Smithuis sr, who is a professor at Oxford university and happens to be the brother of Robin Smithuis.

Click here to watch the video of Medical Action Myanmar and if you like the Radiology Assistant, please support Medical Action Myanmar with a small gift.