Non-traumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage

Amber Bucker, Henriette Westerlaan, Aryan Mazuri, Maarten Uyttenboogaart and Robin Smithuis

University Medical Center Groningen and Alrijne Hospital in Leiderdorp, the Netherlands

Any type of bleeding inside the skull or brain is a medical emergency.

The most common causes of hemorrhage are trauma, haemorrhagic stroke and subarachnoid haemorrhage due to a ruptured aneurysm.

Complications are increased intracerebral pressure as a result of the hemorrhage itself, surrounding edema or hydrocephalus due to obstruction of CSF.

In this article we will discuss non-traumatic hemorrhages.

They will be discussed by their location, because that is frequently the clue to the differential diagnosis.

Then we will discuss further imaging to get to a specific diagnosis.

Finally specific diseases that present with intracerebral hemorrhages will be presented in more detail.

Press ctrl+ for larger images and text on a PC or ⌘+ on a Mac.

Most images can be enlarged by clicking on them.

Localization of hemorrhage

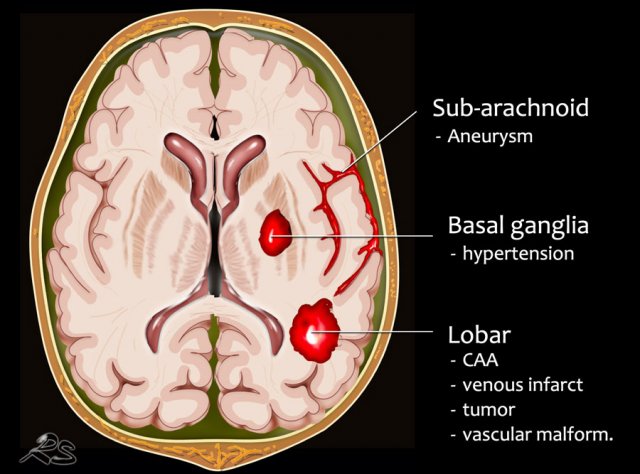

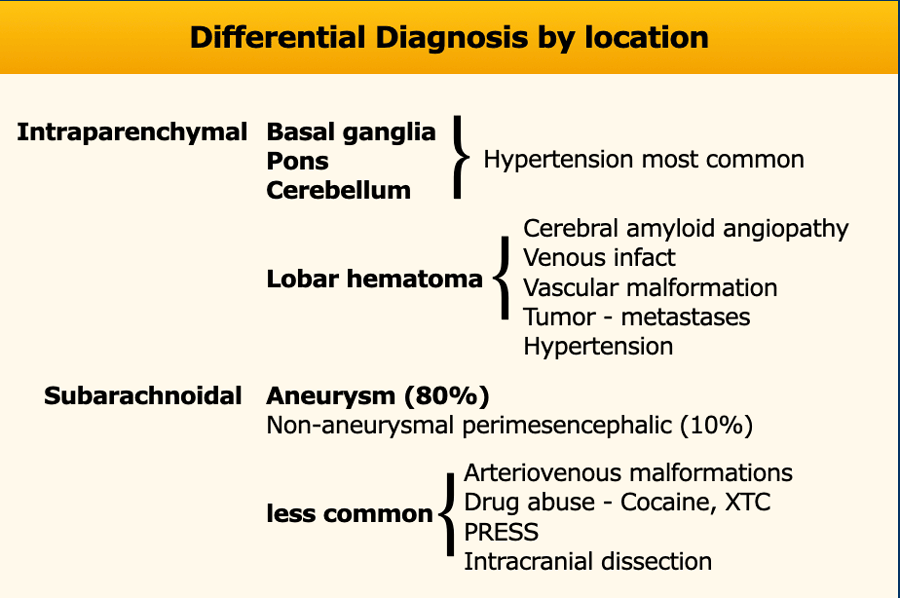

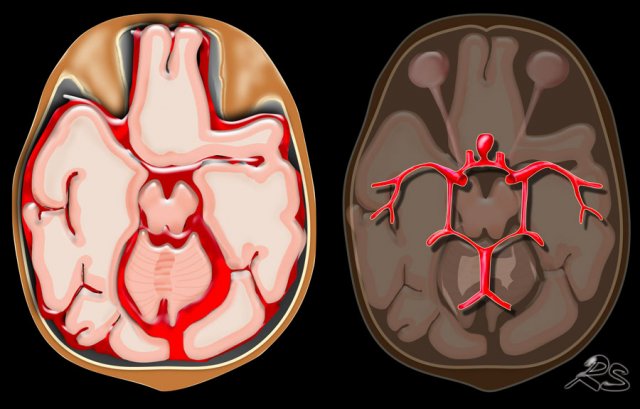

Knowing the location of a hemorrhage is often the key to the differential diagnosis especially in non-traumatic bleeding.

Extra-axial hemorrhage - Intracranial extracerebral

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage is acute bleeding under the arachnoid. Most commonly seen in rupture of an aneurysm or as a result of trauma.

Intra-axial hemorrhage - intracerebral

- Lobar hematoma is located in the periphery of a lobe. The most common cause is cerebral amyloid angiopathy, but can also be seen in hypertension, tumor, vascular malformation, venous infarction and many other diseases.

- Centrally located hemorrhage in basal ganglia, pons or cerebellum. The most common cause is hypertension.

85% of non-traumatic hemorrhages are seen in patients with hypertension or cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA).

In hypertension the hemorrhages are typically in a central position in the basal ganglia, pons, thalamus and cerebellum, while in CAA they are typically more in a peripheral location - deep in the frontal, parietal or temporal lobes - also called lobar hemorrhages.

The differential diagnosis in a patient with an intracerebral hemorrhage however is much larger and also includes:

- Vascular malformations like arteriovenous malformation (AVM), dural arteriovenous fistulas (dAVF), aneurysms, cavernoma, DVA (very rare).

- Infarction with hemorrhagic transformation

- Hemorrhagic venous infarction in sinus thrombosis

- Hemorrhagic primary brain tumors or metastases

- Drug abuse

- PRESS

- Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome

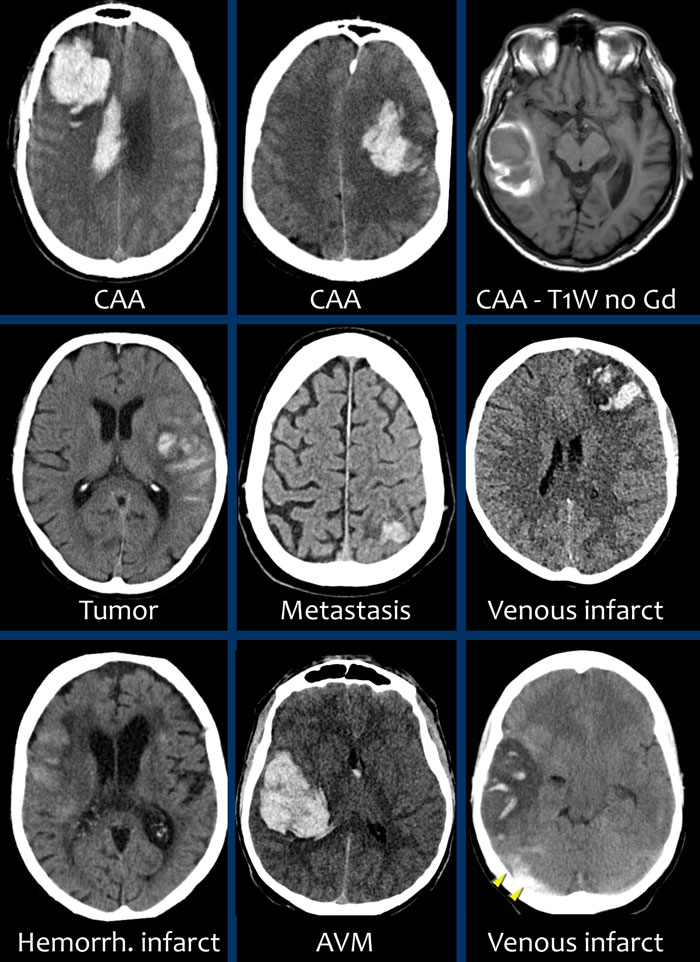

Lobar hemorrhage

Lobar hemorrhages are located in the periphery of the cerebral lobes unlike hypertensive bleeding which usually is located more centrally.

The most common cause especially in elderly is cerebral amyloid angiopathy, but also hypertension because of its high prevalence.

Other causes:

- Hemorrhagic tumor or metastases

- Cavernous malformation

- AVM

- dAVF

- Venous infarction

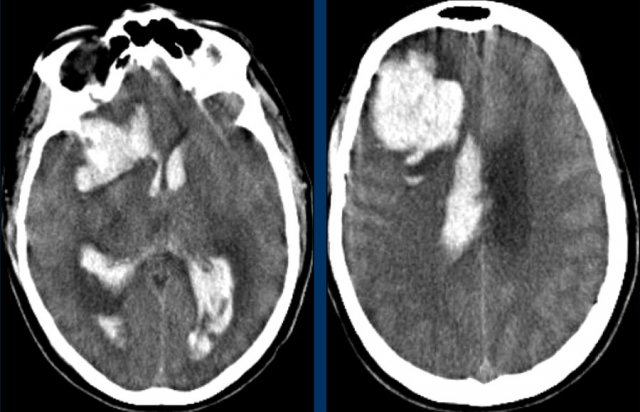

Here some examples of lobar hemorrhages.

Bleeding into the ventricular system in lobar hemorrhage is not as common as in hypertensive hemorrhage because of the more periferal location.

Only when they are very large, they can cause bleeding into the ventricular system (fig).

This patient died the next day.

No definitive diagnosis was made, but it was assumed that this was a case of CAA.

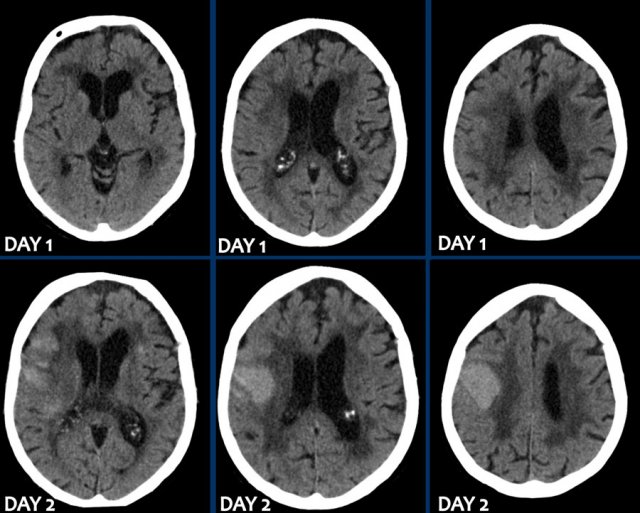

Basal ganglia

Hemorrhage in the basal ganglia is typically seen in hypertension.

Hypertensive hemorrhage typically occurs in elderly patients and is usually in a central location.

This differentiates hypertensive bleeding from hemorrhage in patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) which are more peripheral in location, although overlap can occur.

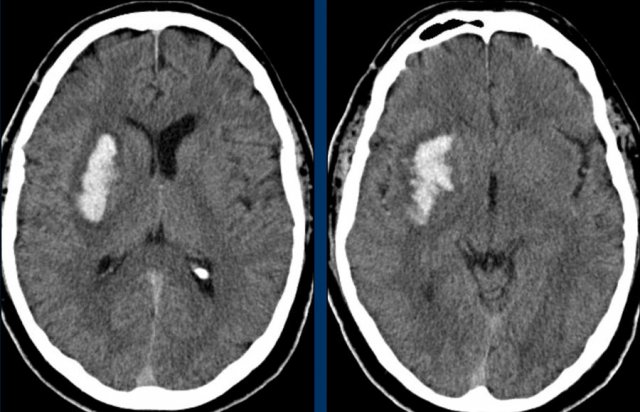

The images show a typical hypertensive hemorrhage in the putamen, which is the largest and most lateral part of the basal ganglia.

Continue with the follow up images...

On a follow up scan only parenchymal loss is seen in the putamen where the hemorrhage was located (arrow).

The putamen is vascularized by the lenticulostriate arteries (LSa).

The LSa are small diameter end vessels that originate at a right angle from the artery of Charcot without the gradual stepdown in size that occurs in the distal cortical vessels.

Their internal pressure may be very high and for this reason the LSa are particularly susceptible to damage from hypertension, the formation of small aneurysms and rupture (3) (ref).

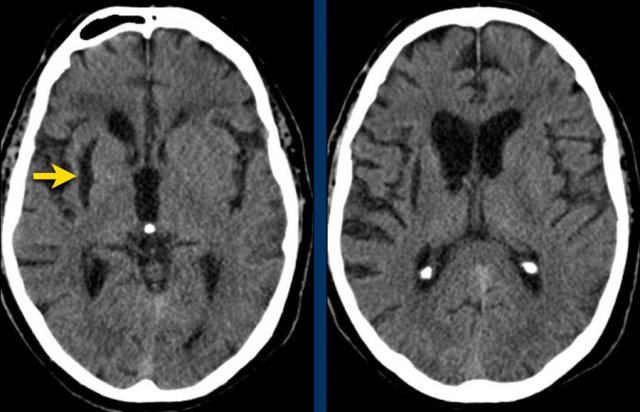

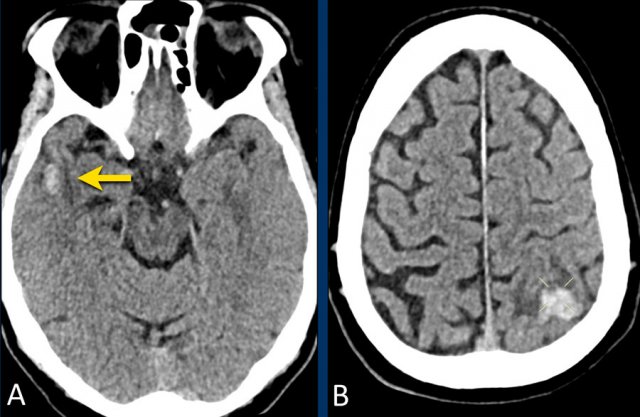

The first three images show a large hematoma in the basal ganglia on the right with massive edema.

The follow up image one year later shows linear cavitation due to tissue loss (arrow) and hypodensity of the basal ganglia as a result of gliosis.

Caudate nucleus

The images show a hemorrhage in the basal ganglia in a patient with longstanding hypertension.

It is located in the head of the caudate nucleus.

The head of the caudate nucleus receives its blood supply from Heubner’s artery and the lenticulostriate arteries,.

A rupture in these arteries causes parenchymal hemorrhage.

The presence of an intraventricular haematoma is considered a poor prognostic factor due to the obstruction to CSF with hydrocephalus and raised intracranial pressure.

Thalamus

Bleeding in the thalamus is typically seen in hypertension.

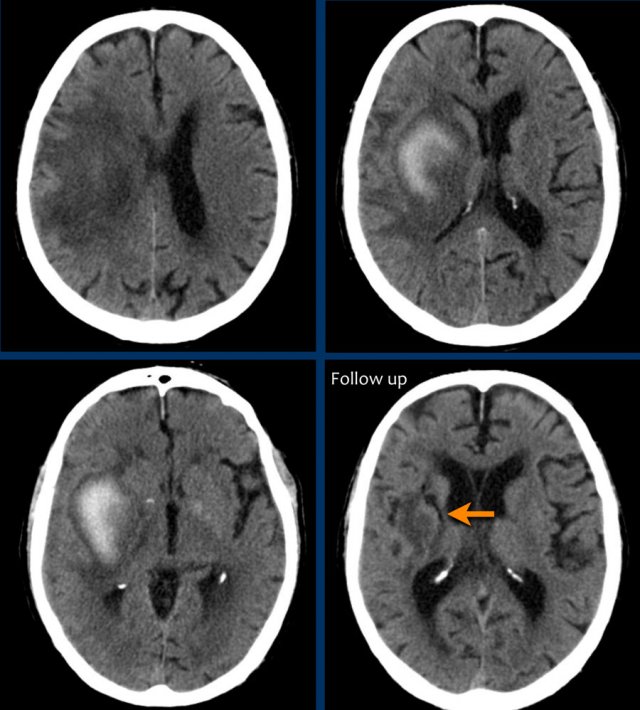

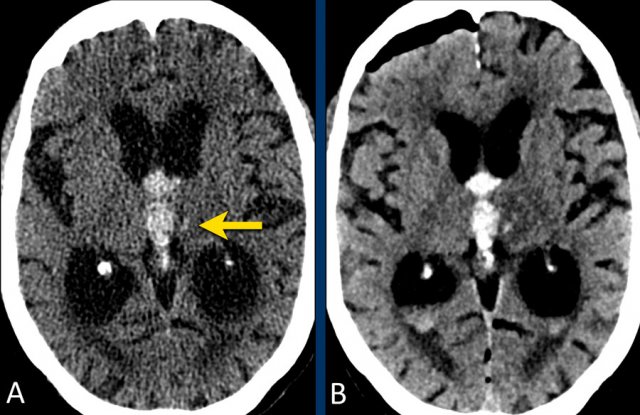

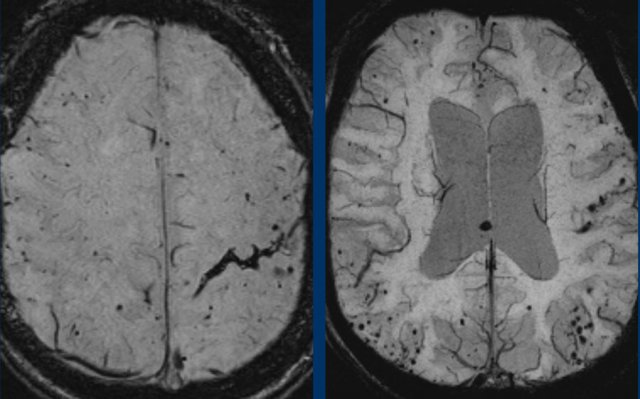

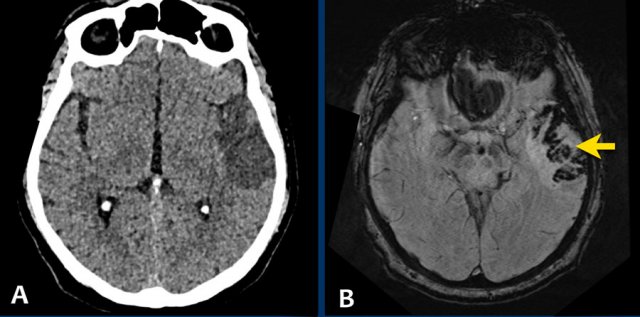

This patient presented with hydrocephalus due to an intraventricular hemorrhage (left image).

Note the very small hyperdensity in the left thalamus, which is the origin of the hemorrhage.

Follow-up one day later (right image).

The patient underwent surgery with placement of a ventricle drain to treat the hydrocephalus.

Note the hypodense thalamus on the left side with the persistent medially located hyperdense focus.

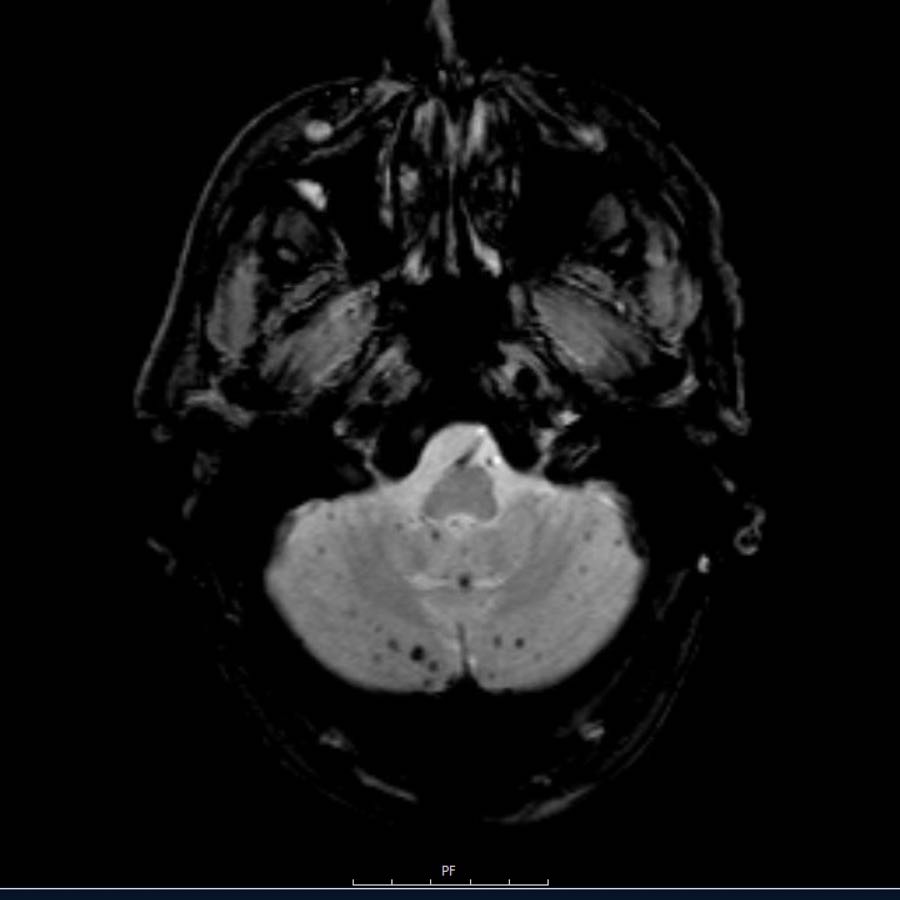

Cerebellar

This patient presented with a cerebellar hemorrhage.

The gradient echo-images show multiple microbleeds.

This can be the result of long standing hypertension due to the central location of some of the microbleeds.

Subarachnoid

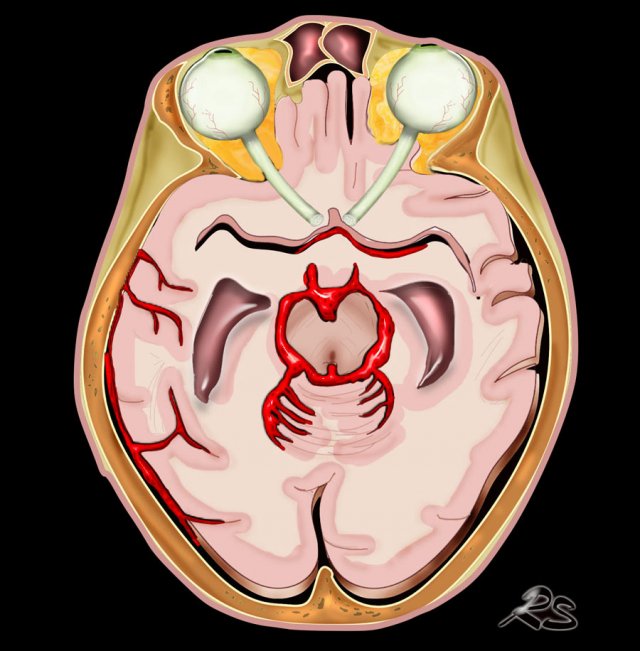

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is bleeding in the subarachnoid space between the arachnoid and the pia mater.

The most common cause is trauma.

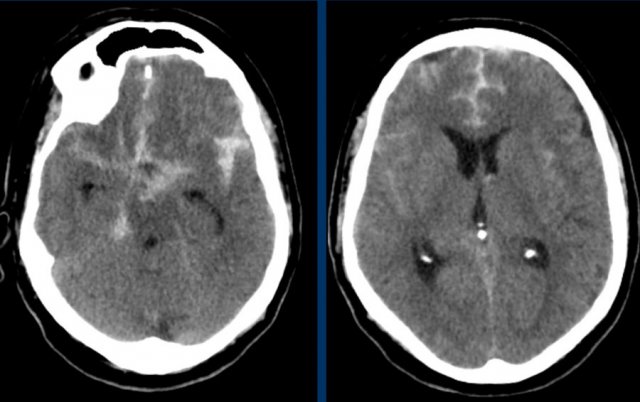

Non-traumatic SAH is usually the result of aneurysmal rupture with spread of blood into the subarchnoidal cisterns (fig).

The first choice of imaging modality in a patient with a clinical suspicion of SAH is a non-enhanced CT scan (NECT).

NECT is positive for SAH in 98% within 12 hours of onset.

If the suspicion is strong, but the CT is negative, a lumbar puncture is performed to detect blood in the CSF.

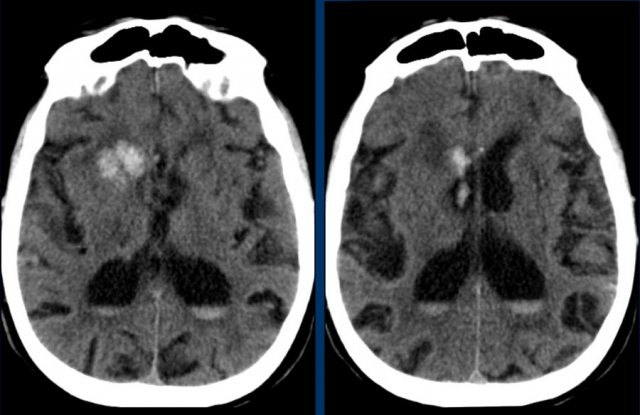

The images show a subarachnoid hemorrhage as a result of rupture of an aneurysm of the left middle cerebral artery (arrow).

Subarachnoid hemorrhage is discussed in more detail here.

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA)

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is a disorder characterized by deposits of amyloid in the walls of the small leptomeningeal and cortical arteries resulting in leukencephalopathy and hemorrhage.

The hemorrhages can be divided in macrobleeds or lobar hemorrhages, microbleeds and subarachnoid hemorrhages that result in cortical superficial siderosis.

It is not associated with systemic amyloidosis.

The major symptoms are neurologic deficits, dementia and epilepsia.

The epilepsia is caused by the hemosiderin deposits near the cortex of the brain.

The major risk factor is increasing age.

These small hemorrhages are also called microbleeds.

Notice how numerous these small hemorrhages are and primarily located in the perifery of the brain.

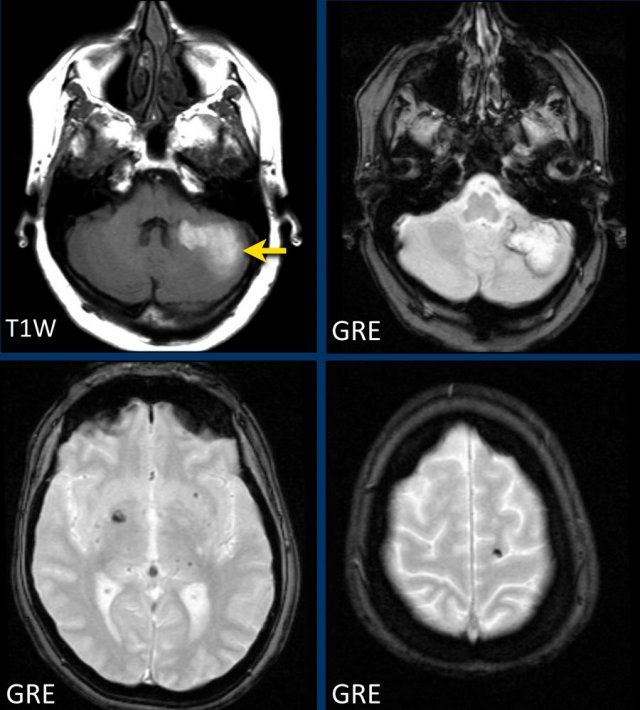

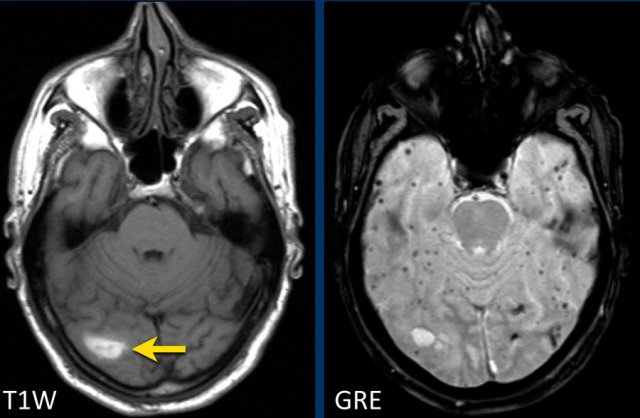

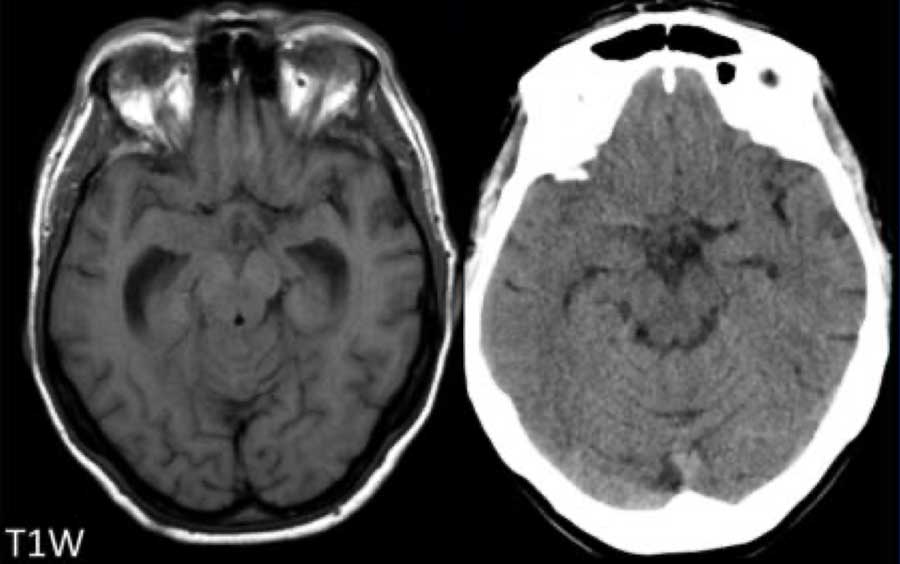

This patient presented with a cerebellar hematoma.

Continue with the T1W-image...

The T1W-image shows a hyperintense hemorrhage (arrow).

Hypertensive intracranial haemorrhage together with CAA make up 80% of the causes of intraparenchymal hematomas.

Think of CAA if you see multiple peripheral or lobar haemorrhages in an elderly patient.

Dutch type of hereditary CAA

The Dutch type of hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy is the most common form.

Stroke is frequently the first sign of the Dutch type and is fatal in about one third of people who have this condition.

Survivors often develop dementia and have recurrent strokes.

About half of individuals with the Dutch type who have one or more strokes will have recurrent seizures.

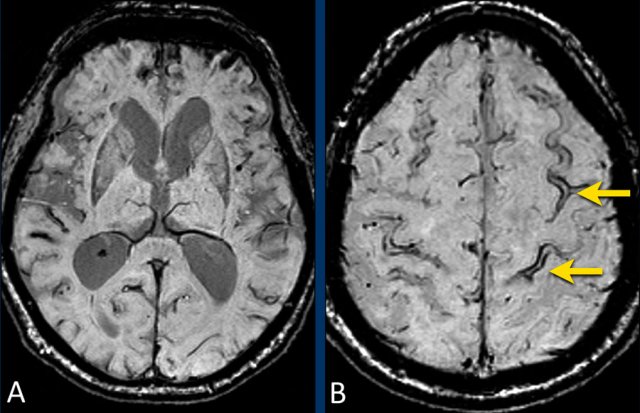

Cortical superficial siderosis in CAA

CAA-related bleeds include:

- Macrobleeds - symptomatic lobar hemorrhages

- Microbleeds - small and typically silent peripherally located

- Cortical superficial siderosis (cSS) - cortical subarachnoid hemorrhages that follow the curvilinear shape of the surrounding cerebral gyri

In superficial siderosis the proximity to the cortical surface appears to be the trigger for transient focal neurologic symptoms or amyloid spells.

CAA patients with widespread cortical superficial siderosis have a far greater chance for recurrent hemorrhage compared to patients without cSS (ref).

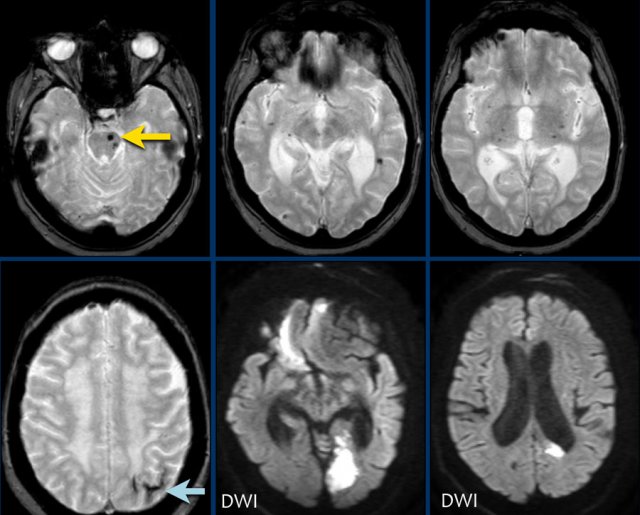

Lobar hemorrhage in Cerebral Amyloid angiopathy (CAA)

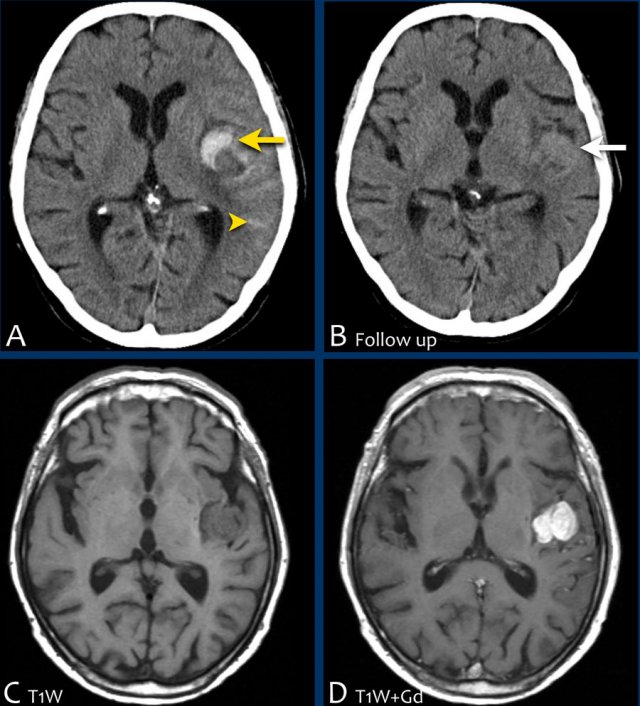

This patient with CAA presented with a large lobar hematoma in the right temporal lobe.

Notice the superficial siderosis (arrow).

This patient with CAA has microbleeds, superficial siderosis and multiple infarcts.

Notice the hemorrhage in the pons (yellow arrow).

There is superficial siderosis in the left occipital region.

The DWI shows infarction in left occipital lobe and reight frontal lobe (with some artifacts).

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

Aneurysmal rupture

As mentioned before a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is bleeding in the subarachnoid space between the arachnoid and the pia mater.

The most common cause is trauma.

Non-traumatic SAH is the result of aneurysmal rupture with spread of blood into the subarachnoid cisterns (figure).

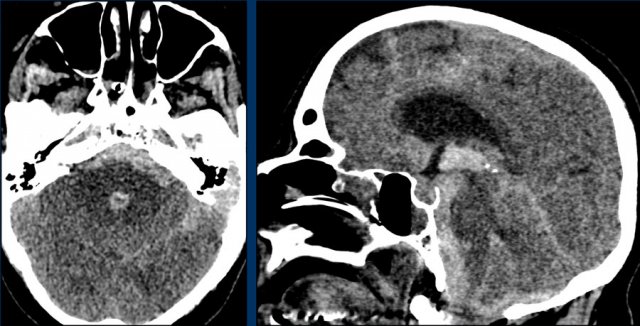

CT images of a patient with a spontaneous SAH.

CTA was performed to look for an aneurysm.

Continue with the DSA...

Notice that there are two aneurysms (arrows):

- carotid siphon

- middle cerebral artery

Both were coiled.

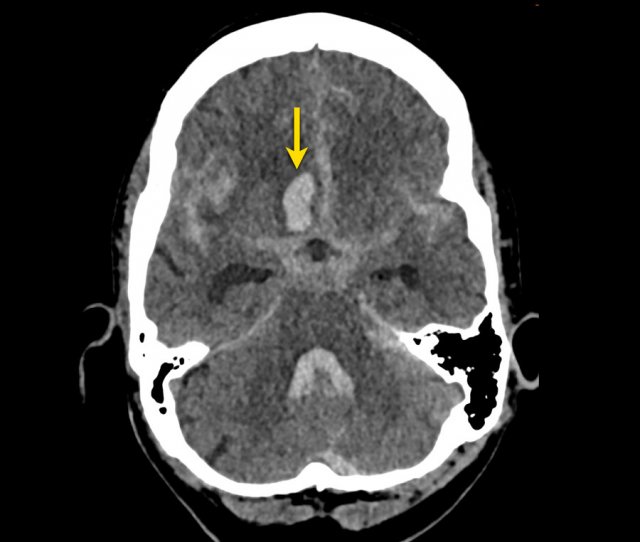

This patient presented with headache for four days and had a stiff neck due to meningeal irritation.

The NECT images show hyperdense blood in the subarachnoid space.

There is an aneurysm of the anterior communicating artery (arrow).

It has a high density and we think that is the thrombus inside the aneurysm.

This means that on a DSA the actual aneurysm may look smaller.

MRI has a lower sensitivity for detecting a SAH than CT in the acute phase.

MRI sometimes detects a SAH in the subacute phase..

The most sensitive sequence are the T2*gradient echo and FLAIR.

These images are of a patient who was suspected of having a SAH a few days ago.

The NECT and most MR sequences were normal.

Continue with the FLAIR images...

The FLAIR images show high signal intensity in the subarachnoid space.

The arrows indicate the interpeduncular cistern anteriorly and the ambient cistern posteriorly.

The differential diagnosis of high signal in the subarachnoid space on MRI is large:

- pus in meningitis

- blood in SAH

- leptomeningeal metastases

- ruptured dermoid

- flow artifacts

In this case it was the result of a SAH.

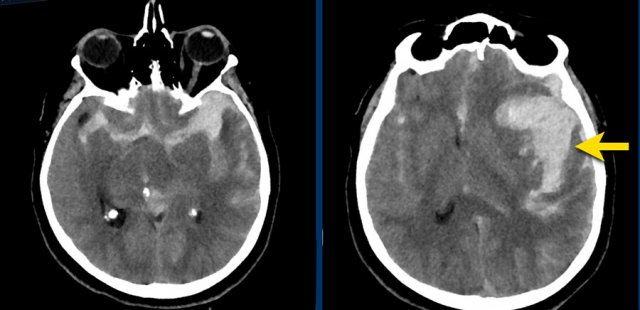

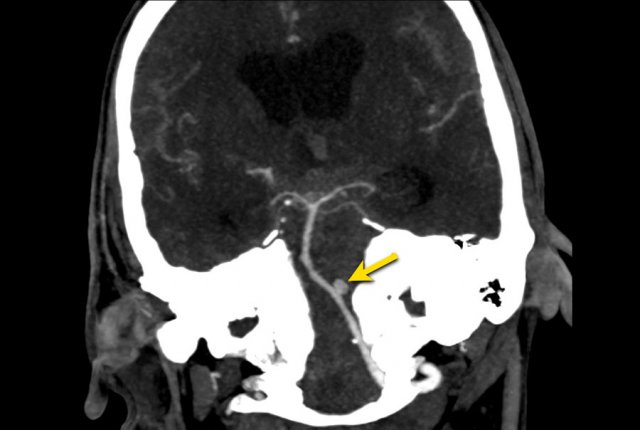

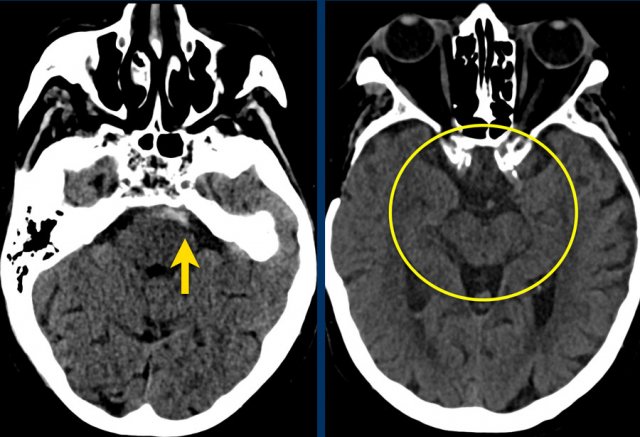

Here we see an example of a subarachnoid haemorrhage on a NECT.

Note the location of blood mainly around the brainstem and in the 3th and 4th ventricle.

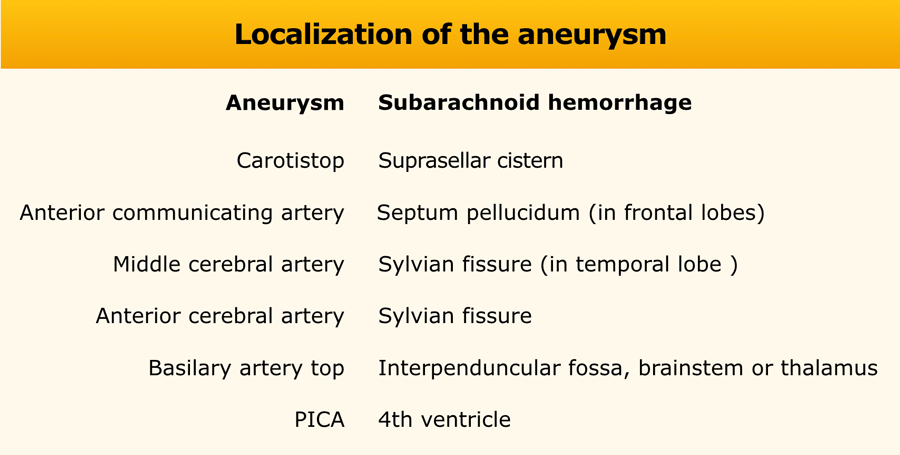

Often the location of subarachnoid blood helps to point in the direction of the aneurysm.

The next step is performing a CT angiography, to search for an aneurysm as the cause of the SAH.

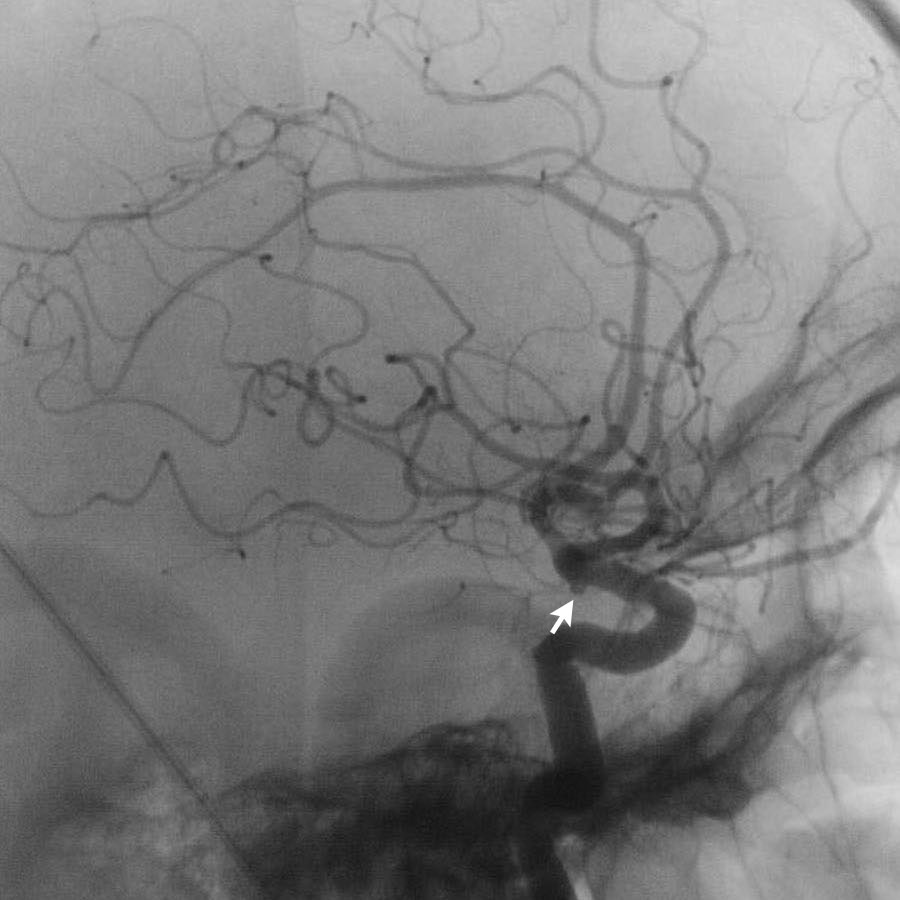

This patient had a aneurysm at the origin of the left posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA).

Also note the hydrocefalus.

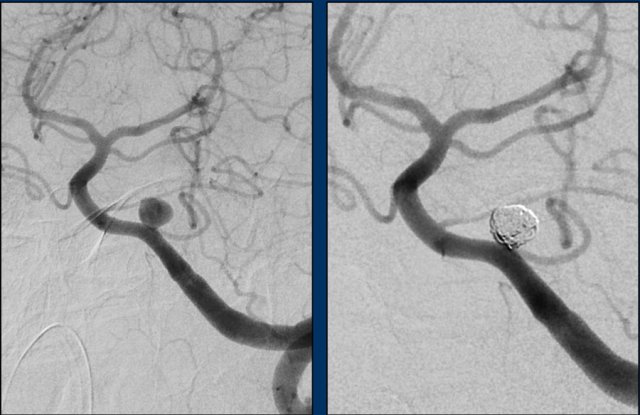

This patient underwent a digital subtraction angiography (DSA) and subsequent coiling.

The DSA showed a saccular aneurysm of the left PICA of 6 mm in maximal diameter with a short, narrow neck.

Saccular aneurysms are the most common type of aneurysm. They are round or lobulated and arise at bifurcations of the Circel of Willis.

They are multiple in 20%. In 5% they measure over 2,5 cm and are called “Giant aneurysms”.

Other type of aneurysms are fusiform (extreme focal ectasia in atherosclerotic disease) and mycotic aneurysms. The latter are seen as peripheral located intraparenchymal clots with white matter oedema surrounding haemorrhage. They are caused by septic emboli in patient with known bacteraemia.

The location of the aneurysm can be suspected from the location of the hemorrhage.

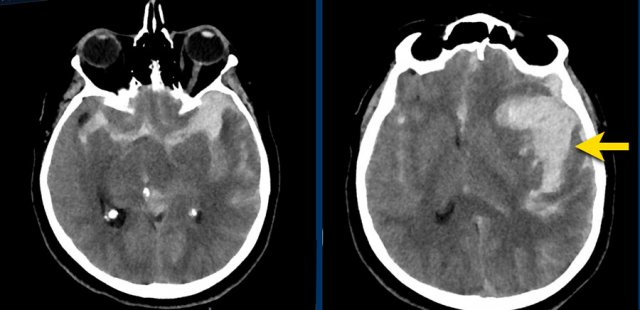

The images show a subarachnoid hemorrhage from a left cerebri media aneurysm.

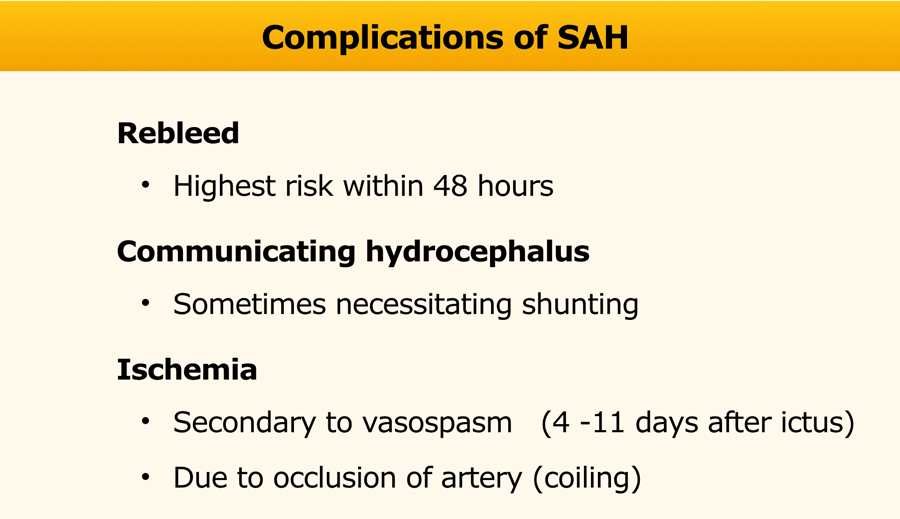

Complications

In the table the complications of a SAH are listed.

Follow-up MRI performed 4 months after coiling shows parenchymal loss in the territory of the left PICA.

MRA showed no recanalisation of the aneurysm after coiling (not shown).

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage in SAH

As discussed earlier an intracerebral hemorrhage can spread to the subarachnoid space.

The opposite is also possible.

When an aneurysm ruptures the pressure of the jet can be so high, that the blood will be injected into the brain parenchyma as can be seen in this example.

This patient presented with a subarachnoidal haemorrhage due to an aneurysm in the anterior communicating artery.

There is also an intraparenchymal heamatoma in the right gyrus rectus (arrow).

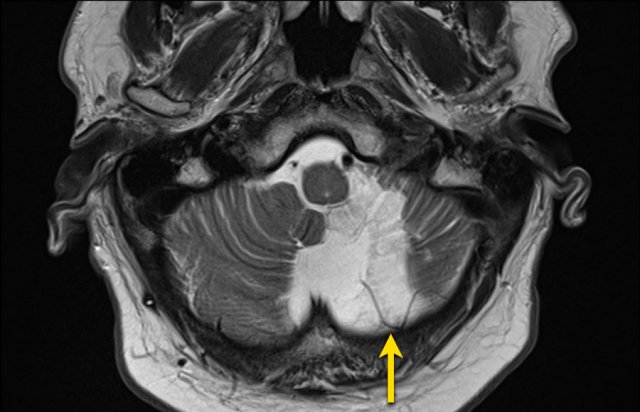

Perimesencephalic SAH

Perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage (PMSAH) is a subarachnoid hemorrhage with a different etiology and prognosis (ref).

It is centered anteriorly to the pons and midbrain but may extend in small amounts into the basal and suprasellar cisterns and even into the Sylvian and interhemispheric fissure.

Perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage is a nonaneurysmal form of SAH.

Patients with a perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage are not at risk for rebleeding in the initial years after the hemorrhage and have a normal life expectancy.

The causes of PMSAH suggest a venous or capillary rupture at the level of the tentorial hiatus.

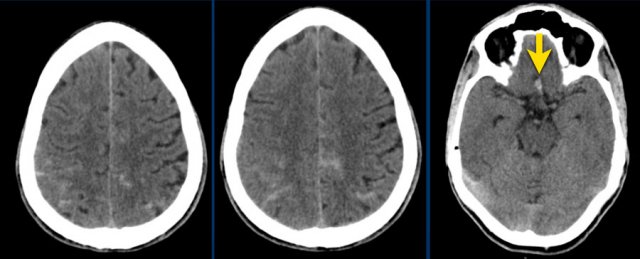

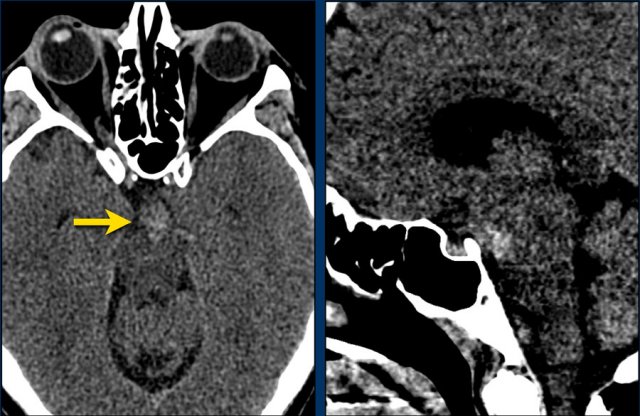

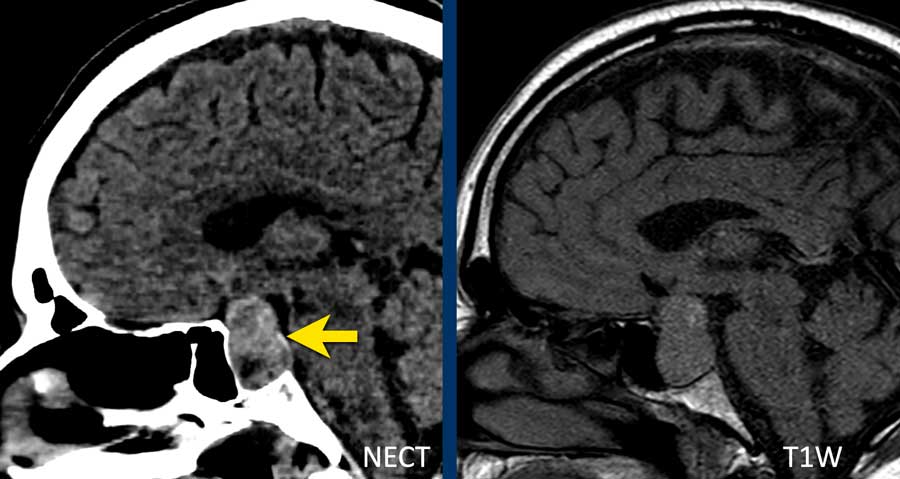

The images show a slightly hyperdense focus in the prepontine and interpedunclair cystern in a patient who presented with acute severe headache.

DSA did not show an aneurysm.

This patient complained of sudden onset headache with the sensation of a “burst” inside his head.

Neurological exam was normal, except for a stiff neck.

The NECT showed a small amount of subarachnoidal blood anterior of the brainstem.

CTA showed no abnormalities.

DSA was not performed.

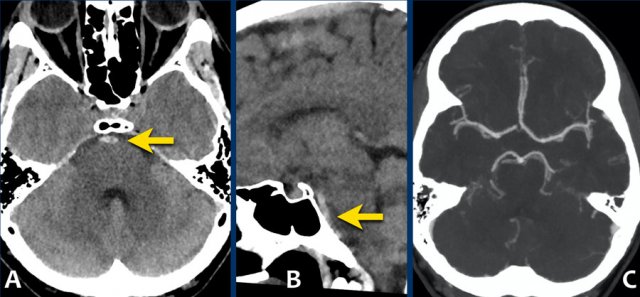

Here another example of a nonaneurysmal perimesencephalic SAH.

Left image: NECT showed a small amount of subarachnoidal blood anterior to the brainstem.

Right image: more cranially, the pentagon, ambiens cistern and the proximal part of Sylvian’s fissures, did not show any blood.

This is a typical presentation of nonaneurysmal perimesencephalic SAH.

The blood is solely located around the brainstem.

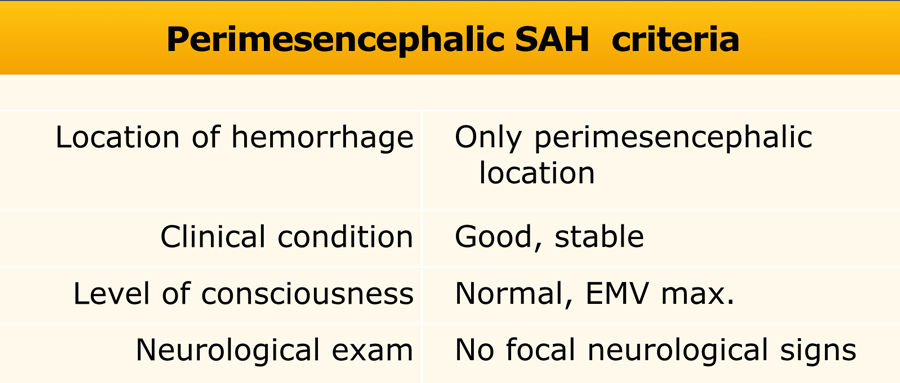

To diagnose a perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal SAH, the patient has to meet all the criteria in the table (8).

If all these criteria apply and the CTA does not show an aneurysm, you do not have to perform a DSA.

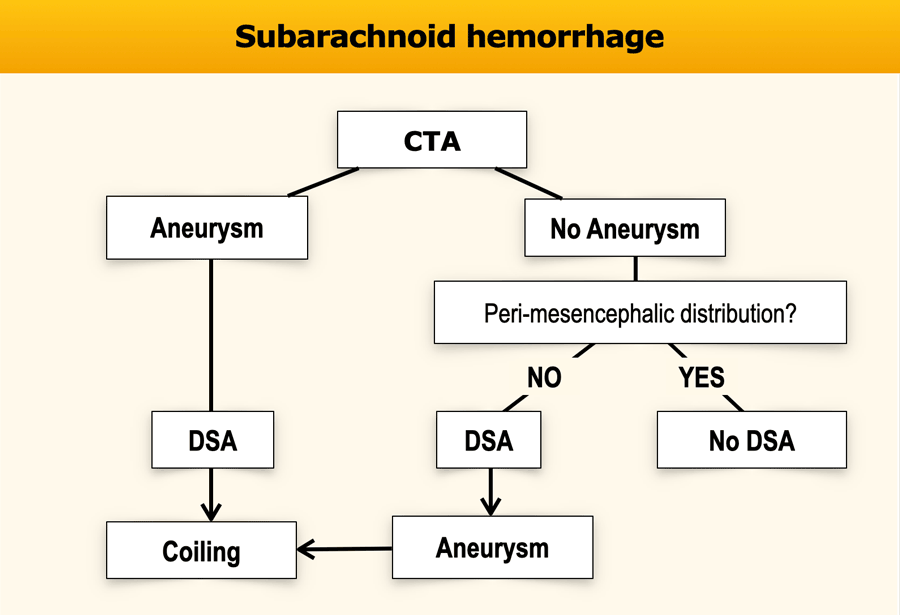

Role of CTA and DSA

In a SAH we usually will find an aneurysm with CTA.

If the CTA does not show an aneurysm we usually continue with a DSA because it has a higher sensitivity.

However if the CTA does not show an aneurysm and the clinical and CT-findings are compatible with a perimesenphalic hemorrhage, no further investigation is necessary (ref 8)

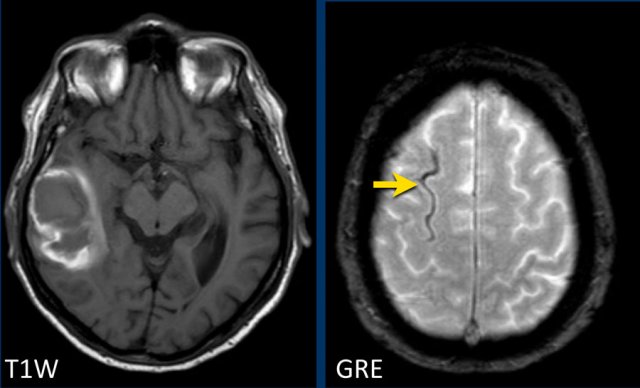

Spontaneous Convexity SAH

Case

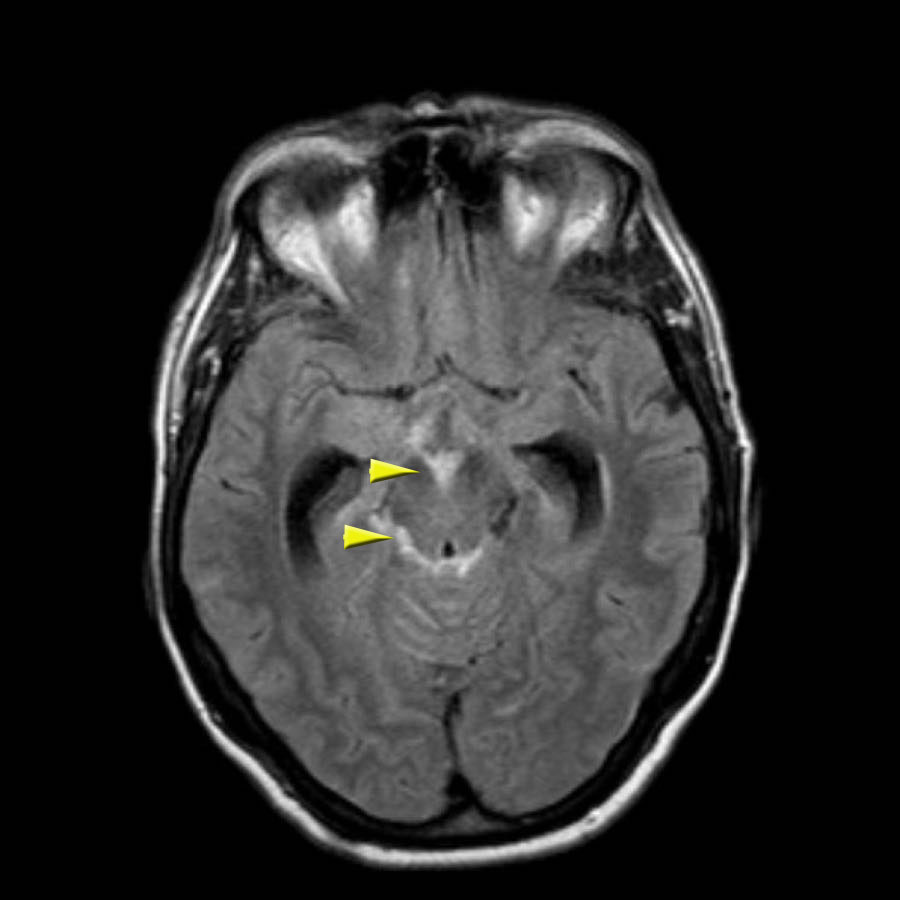

A 68 year old male presented with progressive tremor and weakness of right hand since one week.

The differential diagnosis of the neurologists includes tumor or CVA. Besides hypertension, no relevant medical history.

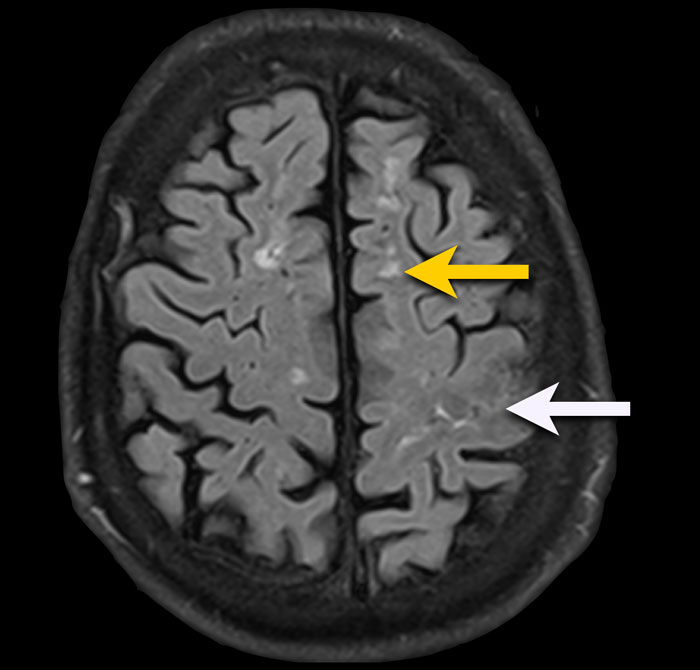

FLAIR-image shows the following findings:

- Subcortical leuko-ariosis (yellow arrow)

- Subtle FLAIR hyperintense signal in the subarachnoidal space of the central sulcus left hemisphere, this can be compatible with blood (white arrow).

FLAIR is an excellent sequence to detect SAH in the subacute phase with almost a sensitivity of 100% from day 4-14.

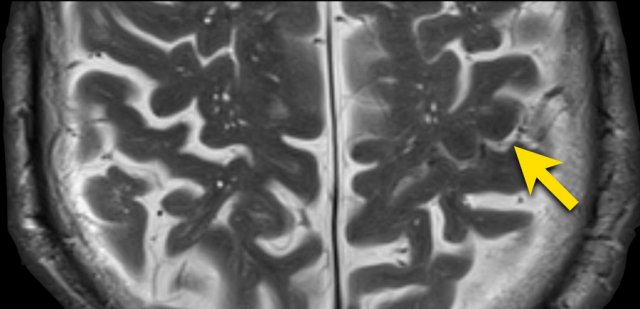

T2W-image confirms the presence of an abnormality in the central sulcus with low signal intensity corresponding to hemoglobin breakdown products.

Susceptibility weighted imaging confirmed the SAH and also reveales multiple small punctate lobar hemorraghes, leading to the diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathie (CAA).

In patients with a spontaneous non-traumatic convexity SAH, consider the following differential diagnosis:

- CAA

Older patients > 65 year - Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS)

Younger patients - Sinus thrombosis

- Vascular stenosis (e.g. ICA origo stenosis)

- Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES)

- Vasculitis

- Arterial dissection

Venous infarction

Whenever you see a hemorrhagic infarction, always think of the possibility of a venous infarction like in this case.

When you scroll through the images, you will notice the thrombus in the right transverse sinus (arrowheads).

Arteriovenous Malformation

A cerebral AVM is an abnormal connection between the arteries and veins resulting in arteriovenous shunting through abnormal vessels called the nidus.

The vessels that make up the nidus are fragile and can rupture, which results in hemorrhage.

Most AVMs have a bleeding risk of 1-2% per year.

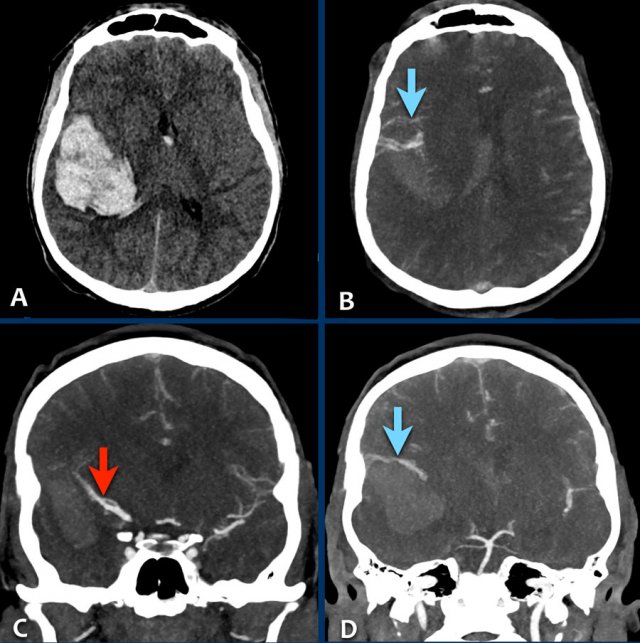

The images are of a young female patient with sudden onset of headache several hours after the use of cocain.

She presented with a left sided hemi paralysis.

- A - NECT with lobar hemorrhage in the right parietal lobe with extension to the ventricles (small dot in foramen of Monroe).

- B - large draining veins are seen.

- C - the arrow points toward the uplifted right medial cerebral artery due to the mass effect of the hemorrhage.

- D - a tiny nidus is seen in connection to the abnormal veins (rather difficult to see on CT).

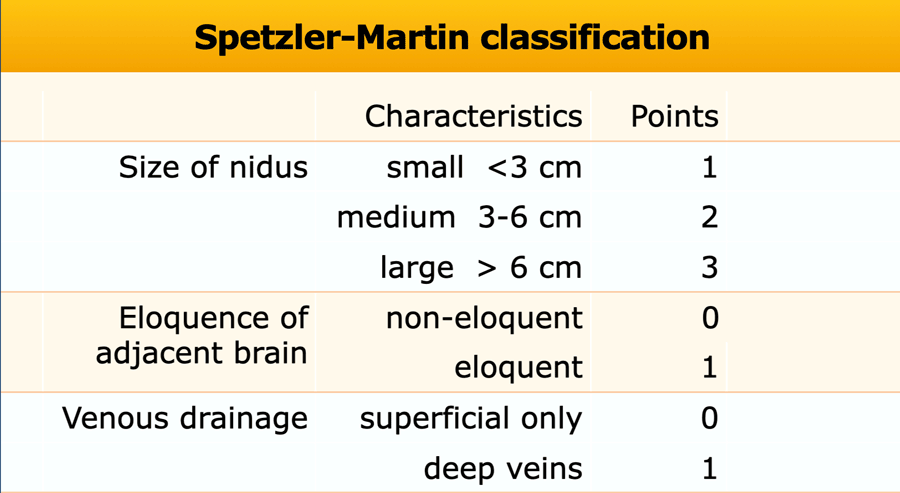

Spetzler-Martin classification

The Spetzler-Martin arteriovenous malformation (AVM) grading system allocates points for various features of intracranial arteriovenous malformations to give a grade between 1 and 5.

Grade 6 is used to describe inoperable lesions.

The score correlates with operative outcome.

eloquent brain

sensorimotor, language, visual cortex, hypothalamus, thalamus, brain stem, cerebellar nuclei, or regions immediately adjacent to these structures

non-eloquent brain

frontal lobe, temporal lobe, cerebellar hemispheres

AVM 2

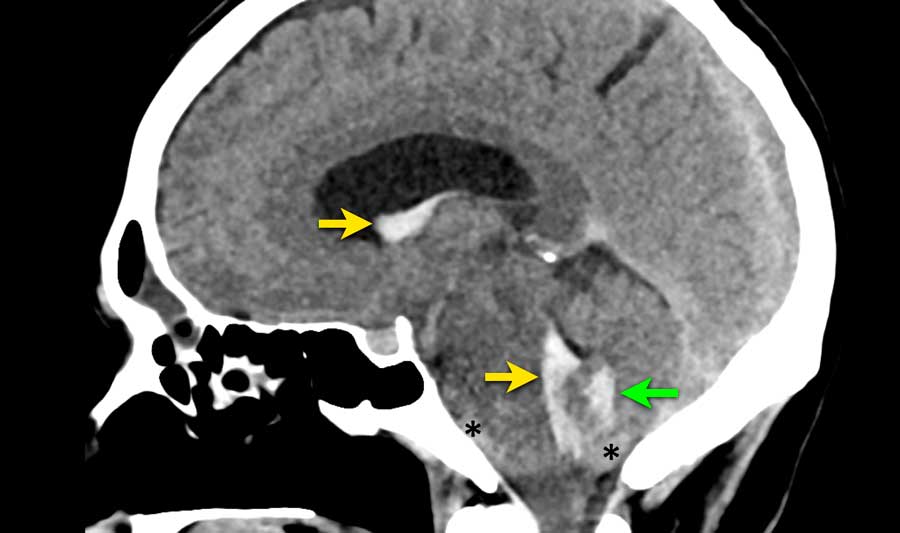

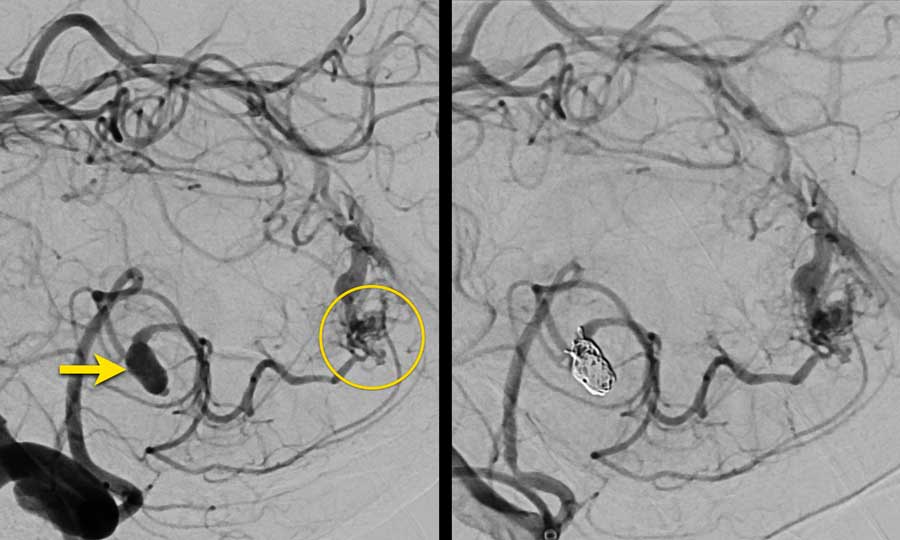

This patient presented with acute onset of severe headache.

Blood is seen in three different locations:

- Intraventricular in the lateral and fourth ventricle (yellow arrows)

- Intraparenchymal in the vermis (green arrow)

- Subarachnoidal in the prepontine cistern and foramen magnum (asterix)

Continue with the CTA...

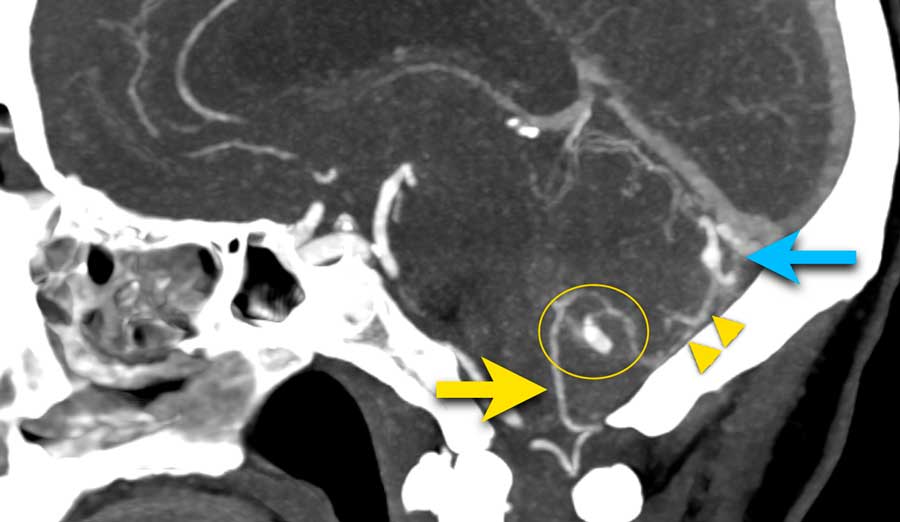

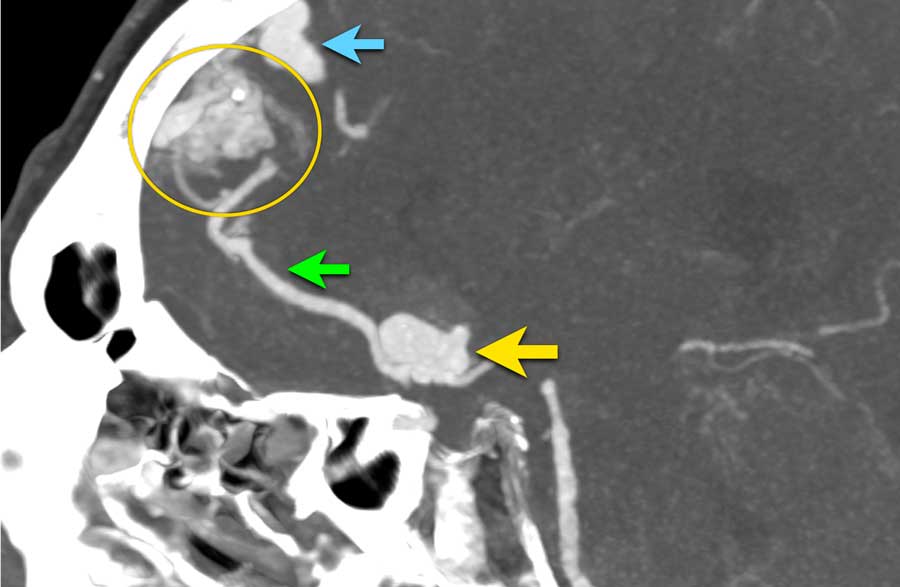

CTA shows a prominent PICA (yellow arrow) with a 7 mm saccular aneurysm (circle) located adjacent to the vermis.

There is a dilated vein (blue arrow) which drains directly into the rectal sinus.

In between the abnormal artery (PICA with aneurysm) and abnormal vein, a network of small vascular structures is seen (arrowheads), suspected of a nidus.

Continue with the DSA...

DSA confirms the right PICA with aneurysm (arrow) which lead to a nidus (circle).

The nidus was drained by either superficial and deep veins (not separately shown here).

Findings are concordant with an AVM - Spetzler Martin 2:

- Small nidus (<3 cm): 1 point

- Location noneloquent site: 0 points

- Pattern of venous drainage by superficial and deep components: 1 point

The saccular aneurysm originating from the PICA was explained as a flow related aneurysm.

As a result of the changed hemodynamics due to the AVM, the vessel wall can become weakened and form an aneurysm.

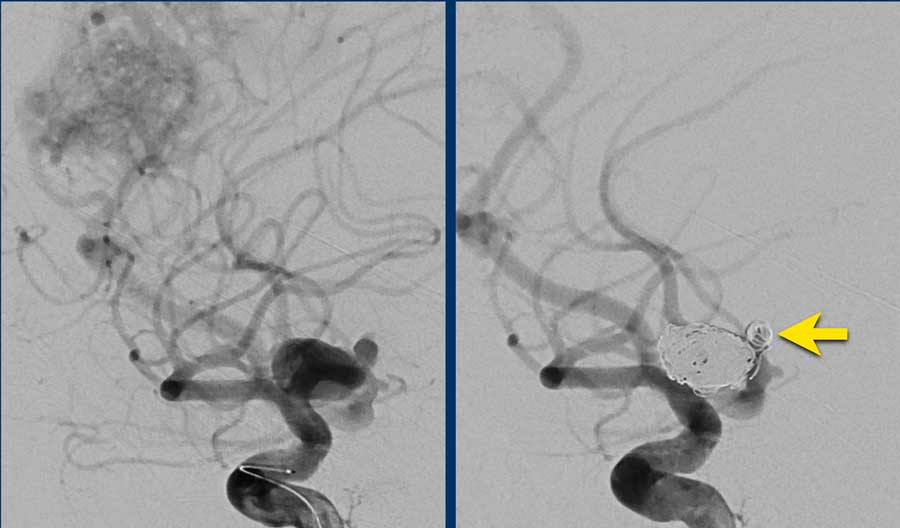

The images show DSA before and after coiling of the aneurysm.

The PICA, nidus and abnormal draining veins (together forming the AVM) still show contrast enhancement.

It was decided not to treat the AVM directly and to opt for follow-up and possibly operative exploration in the future.

AVM 3

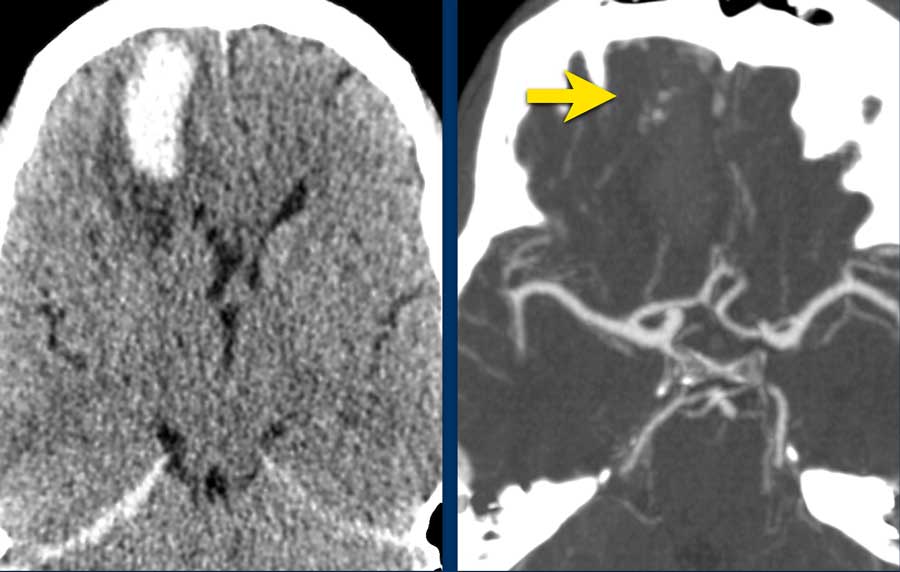

A 55 year old male presented with acute headache and a confused consciousness state.

NCCT shows a lobar parenchymal hemorrhage surrounded by edema (left image).

CTA only showed some dots of contrast (arrow) in the hemorrhage, connected to small abnormal vessels (not shown) below the hemorrhage.

No feeding arteries of draining veins were visible.

The mass effect of the hemorrhage can obscure the underlying cause in the acute phase.

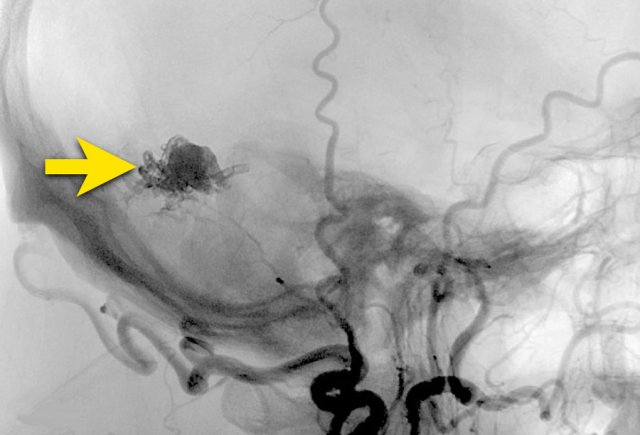

DSA and 3D images from the Right Internal Carotid artery showed an underlying AVM.

- Feeding artery - black arrowheads

- Nidus of the AVM - yellow arrow

- Draining veins - blue arrows

Spetzler Martin 1

- small AVM < 3cm

- a non-eloquent area

- superficial venous drainage

DSA control after surgical removal of the AVM shows no signs of residue.

AVM 4

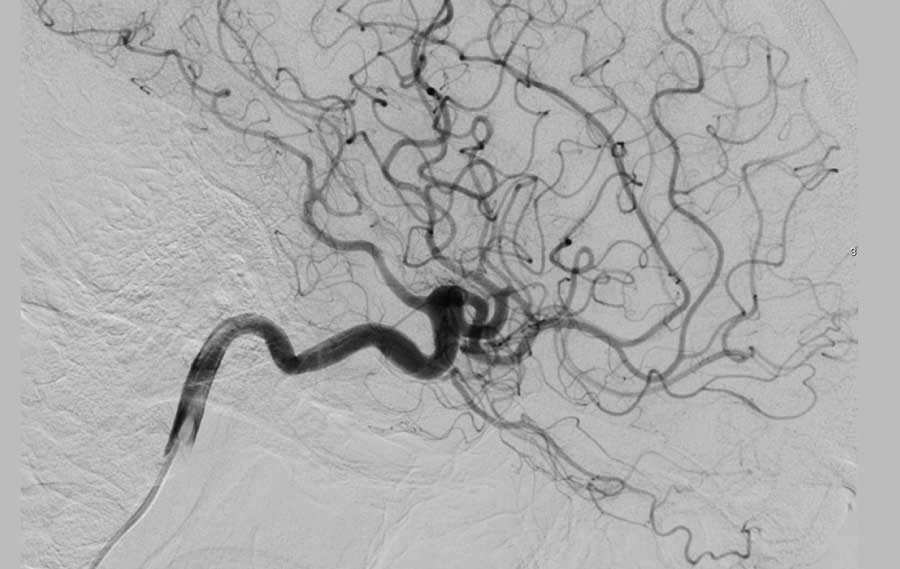

65 year old man complaining of acute onset of headache.

NCCT shows bilateral subarachnoid hemorrhage and a parenchymal hemorrhage (yellow arrow).

CTA show at the location of the parenchymal hemorrhage a flow related aneurysm of the anterior communicans artery, which was considered the cause of the SAH.

Notice the hemorrhage next to the aneurysm (circle).

CTA also showed an AVM with the nidus in the left frontal lobe (green arrow).

In patients with an AVM flow dynamics may change in a way that the arterial walls become weakened and aneurysms may develop.

Lateral view of the CTA:

- Flow related aneurysm with a daughter sac at the base of the aneurysm - yellow arrow

- Feeding artery - green arrow

- AVM nidus - circle

- Dilated draining vein - blue arrow

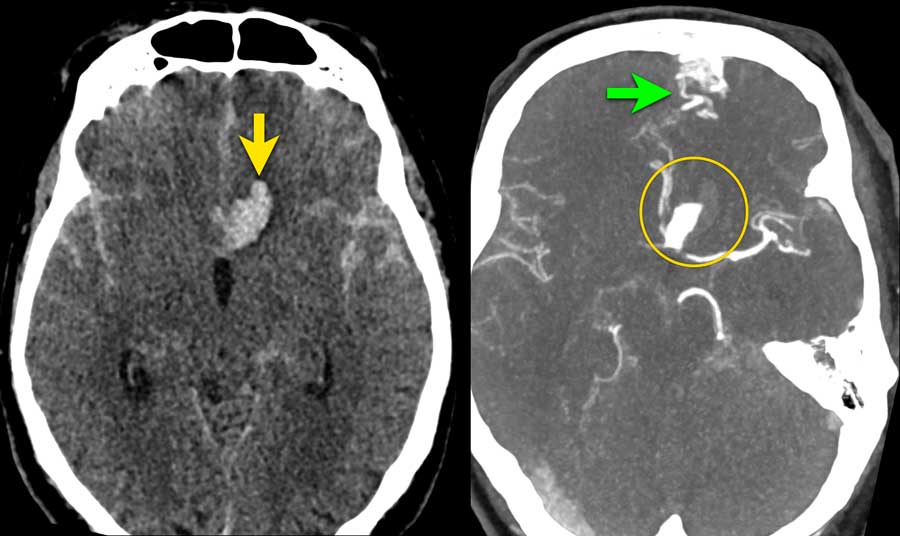

Left image: DSA of the aneurysm before treatment.

Right image: DSA after treatment with separately coiling of the aneurysm and daughter sac (yellow arrow).

It was decided to treat the aneurysm first and remove the AVM surgically in the sub acute phase when the patient has recovered from his subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Dural arteriovenous fistulas (dAVF)

A dural arteriovenous fistula is an abnormal connection between a dural artery and a vein or venous sinus.

Due to the increased venous pressure a variety of symptoms may occur: pulsatile tinnitus, headache, raised intracranial pressure, epileptic seizures, venous infarction or intracerebral hemorrhage.

The presence of cortical venous reflux in patients with DAVF increases the chance of neurological deficits due to venous infarction or hemorrhage.

In contrast to arteriovenous malformation, a DAVF is usually an acquired disorder and may develop after cerebral venous thrombosis.

Although DAVFs may be visible on 3D time of flight MRA, or CT angiography, DSA is still the gold standard to diagnose and classify the type of DAVF.

Treatment consists of endovascular embolization of surgical disconnection.

dAVF 1

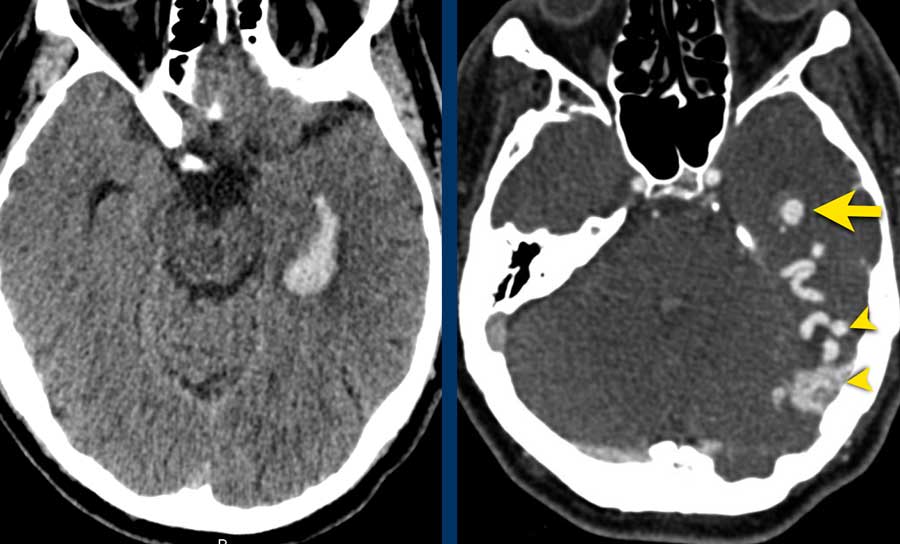

This patient suffered from an intraventricular hemorrhage.

Note the cortical venous reflux (arrowheads) on the CT-angiography with also venous ectasia (yellow arrow) near the temporal horn of the lateral ventricle as the bleeding spot.

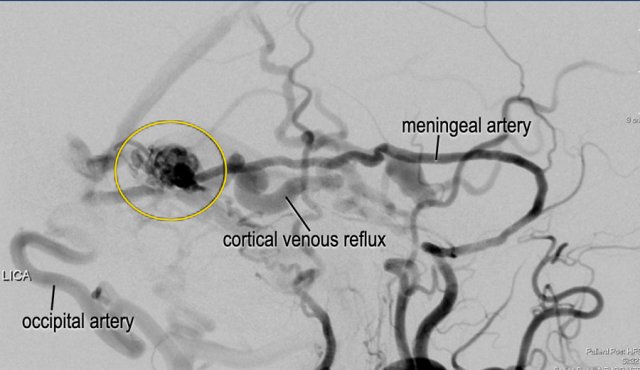

The DSA images (lateral view) confirmed a dural arteriovenous fistula (DAVF) Borden type 3, Cognard type IV.

Note the massive cortical venous reflux with venous ectasia.

After trans-arterial embolization with liquid embolic agents (arrow), there was a complete obliteration of the DAVF.

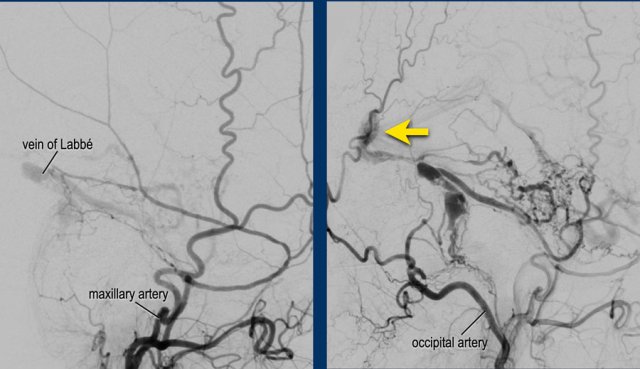

dAVF 2

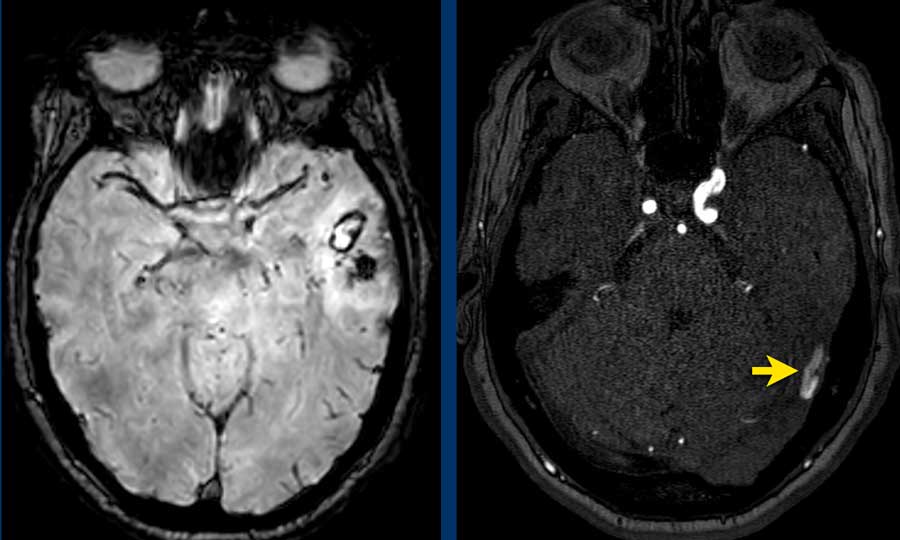

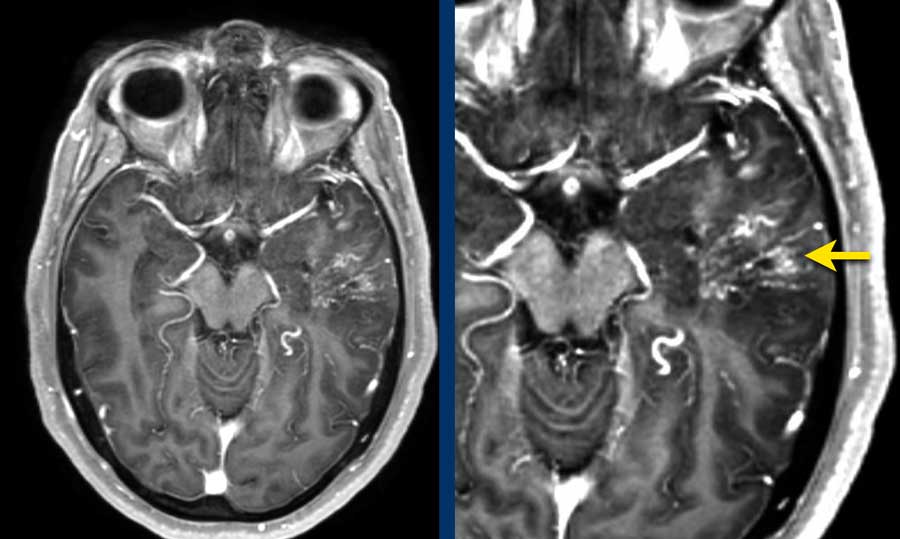

This patient had intermitted speech disturbances. MRI showed a lobar hemorrhage in the left temporal lobe.

On the 3D TOFMRA there was arterialization of the vein of Labbé (arrow).

dAVF 2

Note the massive venous congestion on the T1 with Gadolineum (arrow).

dAVF 2

Note the direct fistula in a subarachnoid vein with cortical venous reflux through the vein of Labbé (arrow).

This is a Borden 3, Cognard type IV.

This patient was treated with embolization through the occipital artery (histroacryl) and middle meningeal artery (Squid ®) with complete obliteration of the DAVF.

The patient recovered completely.

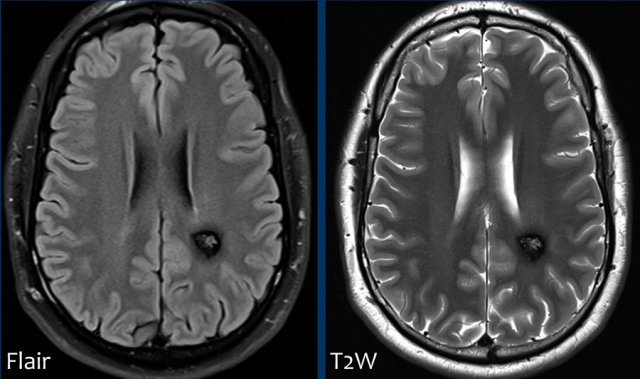

Cavernous malformation

A cavernous malformation, also called cavernoma or cavernous hemangioma, is a vascular hamartoma.

It is a benign mass composed of immature vessels.

Cavernomas may be congenital, but usually form during life.

Patient may be asymptomatic or present with intracranial haemorrhage. Patients of any age may present with a cavernoma.

A cavernous malformation is composed of immature vessels and may bleed.

Imaging may depict various stages of bleeding.

This example shows the typically appearance on MRI named “popcorn lesions”: a complete hemosiderin ring surrounding a heterogeneous lesion.

They are usually located supratentorial, but may less commonly present in the pons or cerebellum.

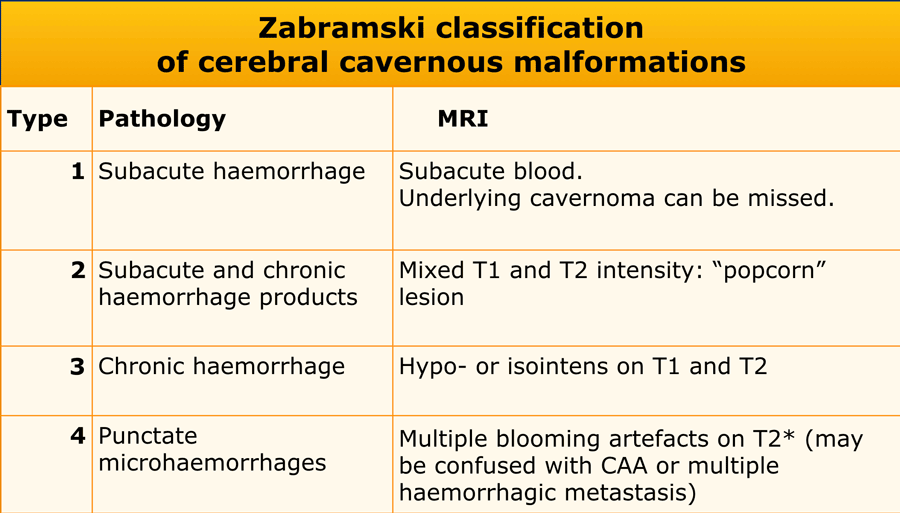

The Zabramski classification has been proposed as a way of classifying cerebral cavernous malformations, and although not used in clinical practice it is useful in scientific publications that seek to study cavernous malformations.

On non-enhanced CT cavernomas are only seen when:

- They are very large - blood products may be hyperdens.

- In recent bleeding

- When they are calcified.

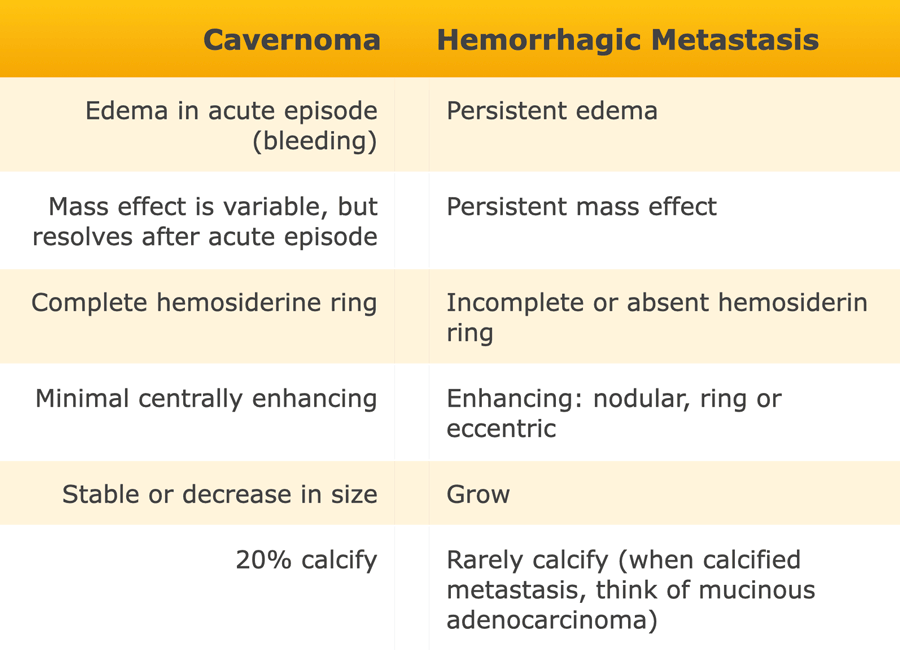

Multiple cavernomas can be confused with multiple haemorrhagic metastasis.

In the table some differences are listed.

Infarction with hemorrhagic transformation

Lobar hemorrhage in hemorrhagic infarction

This patient came to the emergency department with a left-sided hemiplegia and dysarthria.

These symptoms quickly diminished and when they decided to dismiss the patient, the symptoms came back suddenly.

It was diagnosed as an acute infarction in the area of the right middle cerebral artery.

Thrombolytic therapy was started right away.

The next day the patient got worse and the second CT-scan showed a large hemorrhagic infarction in the right acm area.

The next day this patient died.

This patient was submitted to the stroke unit with a recent infarct in the left MCA territory.

Due to delay in presentation outside the thrombolytic window, no thrombolytic therapy was given.

A follow-up NECT (image A) was ordered because of clinically deterioration and showed a well demarcated hypodense area in the left MCA territory. In the hypodense area, very small subtle hyperdens foci were depicted.

MRI several hours later the same day showed foci of hemorrhage (arrow) indicating petechial hemorrhagic transformation of the ischemic infarct.

Hemorrhagic metastases

This cortically located location at the grey-white matter junction is typical of hematogenously metastatic spread.

They usually follow flow-dynamics: 80% anterior circulation vs. 20% posterior.

Metastasis can become so large, that when they bleed, they present as a focal lobar hemorrhage.

50% of hemorrhagic metastases present as a solitary lesion and the other half presents as two or more lesions.

The most common hemorrhagic metastases are:

- Melanoma - 50% present with hemorrhagic metastases

- Renal Cel Carcinoma

- Choriocarcinoma

- Lungcarcinoma

- Breast carcinoma

- Thyroid carcinoma

- Retinoblastoma

Hemorrhagic Brain tumor

Intratumoral hemorrhage

The glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common primary brain tumour to show intratumoral haemorrhage.

In oligodendrogliomas haemorrhage occurs in 20%.

An other common known acute presentation of intratumor haemorrhage is apoplexia due to bleeding in a hypophyseal macroadenoma.

The CT-images show:

- Lobar hemorrhage on a NECT.

There is also some subarachnoid blood.

Pituitary Apoplexia

This patient presented with sudden headache, nausea and vomiting.

He had ptosis of his left eye.

The images show a pituitary macroadenoma with extension into the cavernous sinus.

Note the subtle hyperdensities in the tumour (arrow).

On a T1W non-enhanced image there is mild hyperintensity posteriorly and cranially in the tumor.

These findings suggested intratumoral hemorrhage, which was confirmed at surgery.