CT in Abdominal Trauma

Stephen Ledbetter and Robin Smithuis

Department of Radiology of the Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston and the Rijnland Hospital in Leiderdorp, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

This review is based on a presentation given by Stephen Ledbetter and was adapted for the Radiology Assistant by Robin Smithuis.

Stephen Ledbetter is director of the emergency radiology department of the Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, which is a teaching affiliate of the Harvard Medical School.

This review will focus on the role of CT in the evaluation of patients with traumatic abdominal injuries.

Some of the cases will be presented in an interactive way.

Introduction

Trauma is the leading cause of death under the age of forty.

Of all traumatic deaths, abdominal trauma is responsible for 10%.

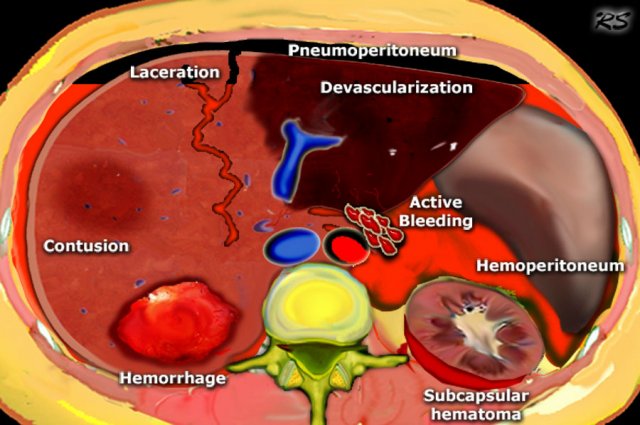

The findings to look for in abdominal trauma are the following:

- Hemoperitoneum

- Contrast blush consistent with active extravasation

- Laceration: Linear shaped hypodense areas

- Hematomas: oval or round shaped areas

- Contusions: vague ill-defined hypodense areas that are less well perfused

- Pneumoperitoneum

- Devascularization of organs or parts of organs

- Subcapsular hematomas

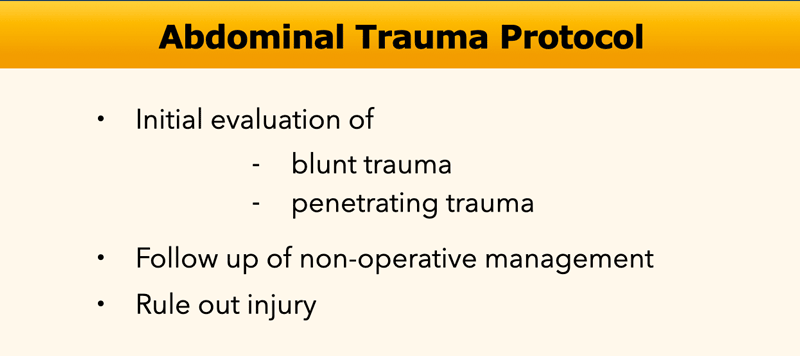

Nowadays there is a trend towards non-operative management of blunt abdominal trauma.

More than 50% of splenic injury, 80% of liver injury and virtually all renal injurys are managed non-operatively, because patients proved to have better outcomes on the long term related to visceral salvage.

CT is used to evaluate patients with blunt trauma not only initially, but also for follow up, when patients are treated non-operatively.

CT is also used to clear patients before they are dismissed from the ER, because CT has a very high negative predictive value and can rule out injury. These patients do not have to be admitted for observation.

The sensitivity and specificity of CT in blunt abdominal injury is 96 to 100% and 94 to 100%, respectively.

CT is also increasingly used for penetrating trauma, which traditionally was evaluated operatively, but the CT-results should be interpreted with caution as the sensitivity and specificity in penetrating abdominal injury is lower than for blunt trauma (31.3% to 100% and 81 to 84%, respectively).

In haemodynamically unstable patients there is already an indication for surgery and you may wanna skip the CT, unless to determine the damage outside the perioperative visual range.

CT Protocol

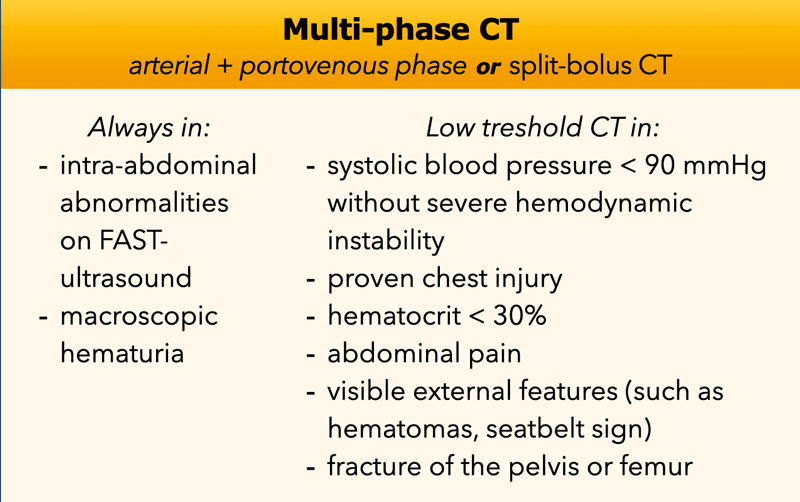

Multiphase CT

In the original article in 2007 the standard method of scanning was the venous phase at 70 seconds post injection and in some cases a subsequent delayed excretory scan 3-5 minutes later if injury was detected on the initial scan.

Nowadays the importance of the arterial scan is recognized.

Here we present the protocol and indications as advised by the radiological society of the Netherlands.

A multi-phase CT abdomen is an accurate form of imaging for the diagnosis or exclusion of vascular injury or active intra-abdominal hemorrhage.

In addition, the scan in the arterial phase can serve as a “roadmap” for the interventional radiologist or the vascular surgeon.

The alternative can be a so-called split-bolus scan (arterial phase and venous phase combined in one scan). The disadvantage of such scans is that it can be more difficult to detect a contrast extravasation due to the lack of a temporal phase difference and the potentially reduced visibility of arteries compared to the pure arterial scan.

The advantage of such a scan is the lower radiation dose.

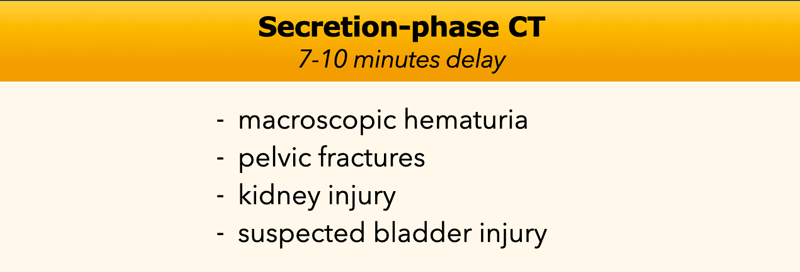

Secretory CT

For the detection of lesions of the collecting system of the kidneys, ureteral and bladder lesions, venous phase CT is moderately sensitive. The sensitivity is increased by adding a secretion phase after 7 to 10 minutes.

In the table the indication for an additional scan in the excretory phase are listed.

Oral contrast can sometimes help to diagnose hollow organ lesions, but did not proof to increase the sensitivity of CT abdomen without oral contrast and is therefore not indicated.

Spleen

The spleen is the most commonly injured solid organ (25%).

The finding of contrast extravasation has great impact on the patients management, because when there is active bleeding, there will be failure of non-operative management in 80% of the cases.

In these patients the need for intervention is almost ten times as high compared to patients without extravasation.

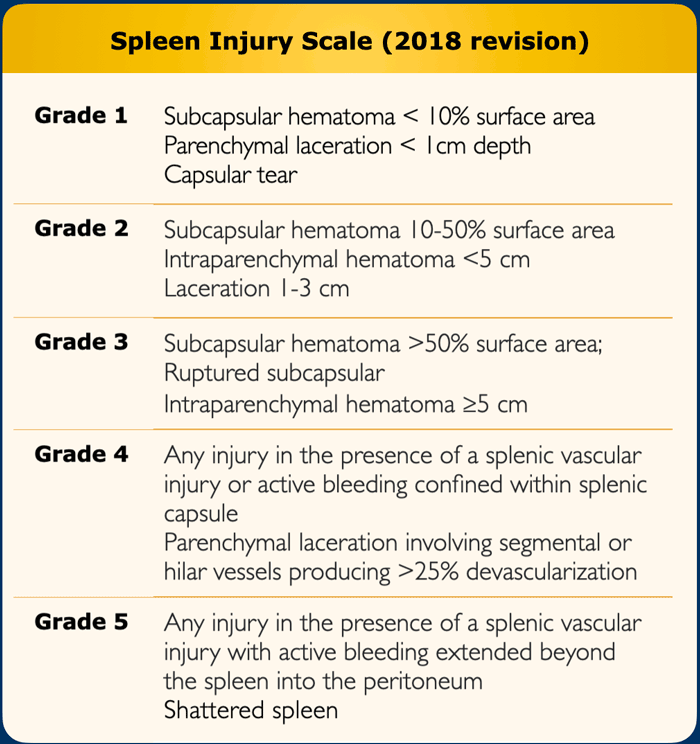

The table shows the CT findings in the spleen injury scale.

Vascular injury is defined as a pseudoaneurysm or arteriovenous fistula and appears as a focal collection of vascular contrast that decreases in attenuation with delayed imaging.

Active bleeding from a vascular injury presents as vascular contrast, focal or diffuse, that increases in size or attenuation in delayed phase.

Vascular thrombosis can lead to organ infarction.

The spleen injury grade is based on the highest grade assessment made on imaging, at operation or on pathologic specimen.

Case 1

Scroll through the images and determine the degree of splenic injury.

Then continue.

The findings are the following:

-

There are multiple poorly defined areas of decreased attenuation.

They are not linear so they are not lacerations.

This is the classic presentation of contusions. - Ribfracture and subcutaneous emphysema due to pneumothorax.

- No contrast blush or hemoperitoneum

Because of the absence of hemoperitoneum or active bleeding, this patient has a good prognosis and will be managed non-operatively.

Case 2

Scroll through the images and describe the lesions.

Then continue.

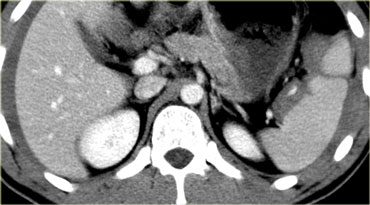

The findings are the following:

- Linear hypodense areas consistent with lacerations.

- Round and oval hypodense areas consistent with intrasplenic hematoma.

- Hemoperitoneum.

Depending on the clinical condition this patient will be managed non-operatively, because there is no active bleeding.

Contrast blush

A contrast blush is defined as an area of high density with density measurements within ten HU (Houndsfield Units) compared to the nearby vessel (or aorta).

The differential diagnosis is:

- Active arterial extravasation

- Post-traumatic pseudoaneurysm

- Post-traumatic AV fistula

How can these entities be differentiated?

- A contract blush that is beyond the borders of the organ, must be extravasation.

- In a pseudoaneurysm or AV fistula the contrast will wash away with the bloodstream.

- If there is active arterial extravasation and we do delayed imaging, the contrast will not wash away

Case 3

Images of a 22-year old male who presented 3 hours after a snowboarding accident with LUQ and left shoulder pain.

Scroll through the images and describe the lesions.

Then continue.

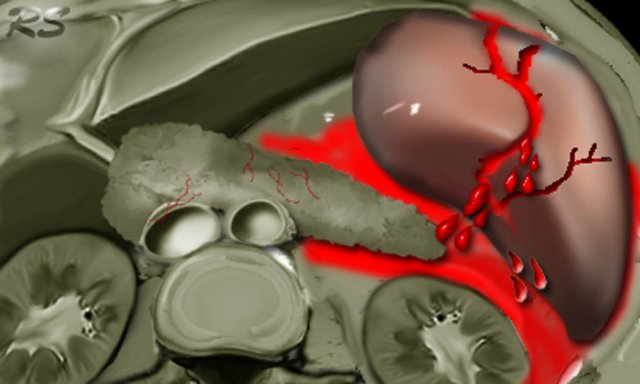

The findings are the following:

- Hemoperitoneum around the spleen and the liver.

- Linear hypodense area in the anterior part of the spleen consistent with laceration.

-

Medially of the spleen is a deposit of contrast consistent with extravasation.

So in this case there is a chance of failure of non-operative management.

Case 4

There are lacerations and also active bleeding with a contrast blush with the density within the range of the density of the aorta.

There also is hemoperitoneum, so this patient will probably need surgery.

Liver

In trauma the liver is the second most commonly involved solid organ in the abdomen after the spleen.

However liver injury is the most common cause of death.

This is due to the fact that there are many major vessels in the liver, like the IVC, hepatic veins, hepatic artery and portal vein.

It is important to remember, especially if you are doing ultrasound, that the posterior segment of the right liver lobe is the most frequently injured part.

This part also involves the bare area and this can lead to retroperitoneal bleeding rather than bleeding into the peritoneal cavity.

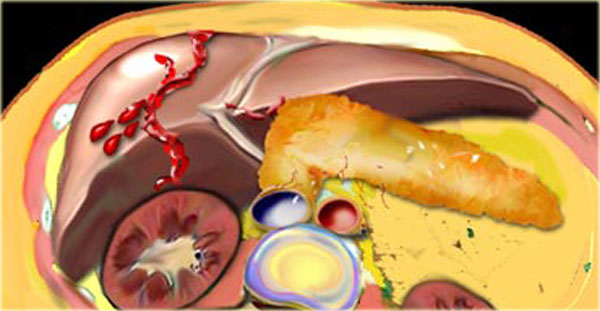

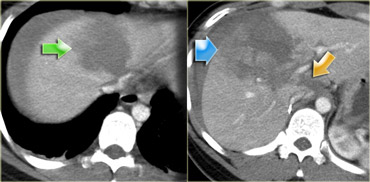

First look at the images on the left of a patient with liver injury.

Describe the findings.

Then continue.

The findings are:

- Green arrow: oval shaped hypodense area consistent with hematoma

-

Yellow arrow: linear shaped hypodense area consistent with laceration.

Notice that this laceration crosses the left portal vein - Blue arrow: vague ill defined hypodense area consistent with contusion

- Fluid around the liver

- There is almost a transsection of the liver, but both lobes do enhance so there is still normal vascular supply.

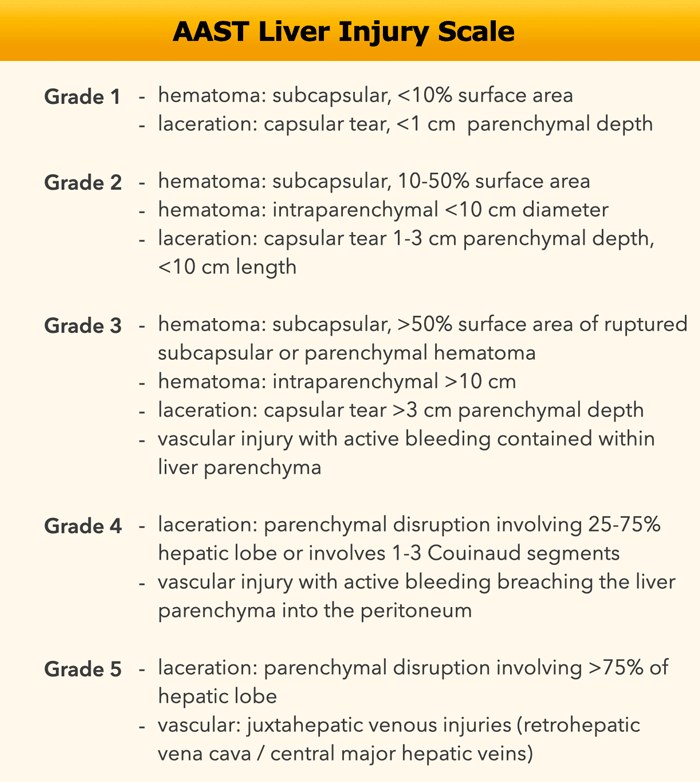

Liver injury scale

The AAST (American Association for the Surgery of Trauma) liver injury scale was revised in 2018.

First look at the images on the left of a patient with liver injury.

What are the CT findings in this case?

The findings are the following:

- Complete devascularization of the right lobe.

- Contrast blush within the intraparenchymal region, but also extention beyond the lateral margin of the liver.

- Hemoperitoneum.

- A second contrast blush at a lower level.

First look at the images on the left of a patient with liver injury.

What are the CT findings in this case?

The findings are the following:

- Subcapsular hematoma greater than 10 cm (i.e. grade 4 injury)

- Contrast blush (arrow)

- No associated hemoperitoneum

So despite the fact that there is a contrast extravasation, this patient will be treated non-operatively and probably will do fine, because there is no bleeding into the peritoneal cavity.

Contrast extravasation is of great importance especially if it is associated with hemoperitoneum.

On the left two more examples of laceration.

Lacerations can be stellate, like the example on the left or branching like the one on the right.

First look at the images on the left of a patient with liver injury.

Questions:

- What contrast materials are on board?

- What is the phase of imaging?

- Where does the contrast surrounding the liver come from?

There is i.v. contrast and images were taken in the portal phase.

There is also oral contrast filling of the stomach.

The contrast surrounding the liver could be a result of stomach or bowel perforation, but since there was no pneumoperitoneum, this was thought to be unlikely.

So the extravasation was thought to be a result of active bleeding and since there is a great amount of contrast surrounding the liver, this was thought to be a huge leak.

At the OR an avulsed right hepatic vein was found.

This diagnosis has a 90-100% mortality and this patient died in the OR.

Some final remarks concerning liver injury:

- Historically liver injury was managed surgically, but at laparotomy it was found that 70% of the bleedings had already stopped by the time the surgeons got there.

- Importantly, patients who went for surgery had more transfusions and more complicaties than patients who were treated non-operatively.

- Today about 80% is managed non-operatively.

- Delayed complications occur in 10-25% of all patients and include:

- hemorrhage (2-6%)

- hepatic abscess (1-4%)

- biloma

Kidney

Penetrating injury

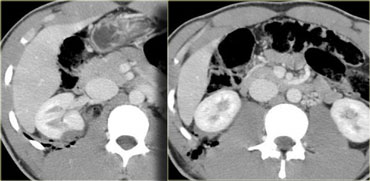

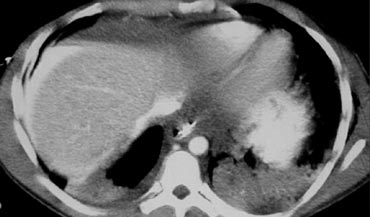

Look at the images on the left and try to answer the following questions:

- What is the role of CT in patients with penetrating trauma?

- What are the findings?

Answers:

- The key role of CT is to determine if there is peritoneal violation and to predict the need for laparotomy

-

Findings:

-

In the vascular phase at 1 minute there is extravasation and fluid in the paracolic gutters indicating peritoneal violation.

There is also a hematoma in the perirenal space. - In the delayed phase there is more extravasation, although it is not clear whether that is due to the active bleeding or contrast comming out of the collecting system

- In the extretory phase it is clear that there is violation of the collecting system

-

In the vascular phase at 1 minute there is extravasation and fluid in the paracolic gutters indicating peritoneal violation.

The next question is, whether the protocol is correct or do we need to give rectal contrast to see if there is bowelperforation, because there is a penetrating trauma?

In this case the answer is no, do not give this patient rectal contrast.

The reason is that we already have reached the treshold for this patient to go to the OR.

There are 3 reasons for this patient to go to surgery:

- Active bleeding

- Peritoneal violation (fluid in the paracolic gutters)

- Violation of the collecting system.

If rectal contrast was given at the start of the examination, this might pose the problem that it would have been unclear, whether the contrast deposition was due to active bleeding or bowel perforation.

So the bleeding could have been missed.

Rectal contrast should only have been given if there were no other findings in need of surgery.

Although this patient had severe renal injury, there was no hematuria.

This is often the case in penetrating trauma and does not rule out renal injury.

In blunt trauma however the abcense of hematuria does rule out renal injury.

On the left another patient with a penetrating injury due to a knife stab in the flank.

The CT demonstrates nicely, that the injury is limited to the retroperitoneal space with a small renal hematoma.

There is no sign of peritoneal violation and on delayed images (not shown) there was no extravasation of the collecting system.

This patient will be treated non-operatively

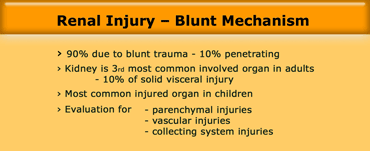

Blunt injury

In 90% of cases there will be renal injury due to blunt trauma.

Unlike in injury to the spleen and the liver, in renal trauma we also need to evaluate the collecting system.

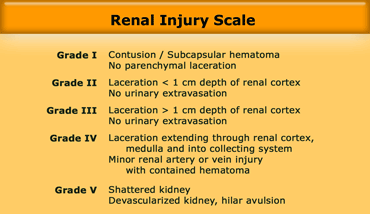

Renal injury scale according to the Organ Injury Scale of the American Association of Surgery of Trauma (AAST)

Renal injury scale according to the Organ Injury Scale of the American Association of Surgery of Trauma (AAST)

The grading system on the left has proven to be of value in the management of the patient.

However unlike the grading for spleen and liver injury it is not that simple to remember.

In grade I there is nothing wrong with the parenchyma, just contusion or subcapsular hematoma.

Grade II and III injuries are either less or greater than 1 cm lacerations, but with no injury to the collecting system.

Grade IV is injury to the collecting system or large lacerations>

Grade V is a shattered or devascularized kidney.

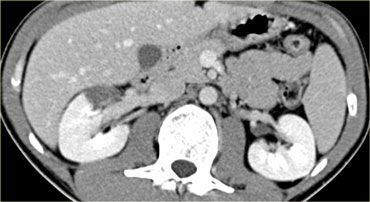

First look at the images on the left of a patient with renal injury after a blunt trauma.

What is the CT grade of injury?

The answer is, that like all grading systems, this system also has its limitations.

What we see on the left is not a laceration, because it is not linear.

It is not a contusion, because it is sharply demarcated.

This is an post traumatic segmental infarction.

On the left a typical subcapsular hematoma, which is also a grade I renal injury.

Some final remarks on renal injury:

- CT has facilitated shift toward NOM.

- 98% of renal injuries now NOM.

- When injury is present, get delayed imaging to evaluate collecting system.

- If there is penetrating trauma, give rectal contrast for possible bowel injury.

Categories of Renal Injuries

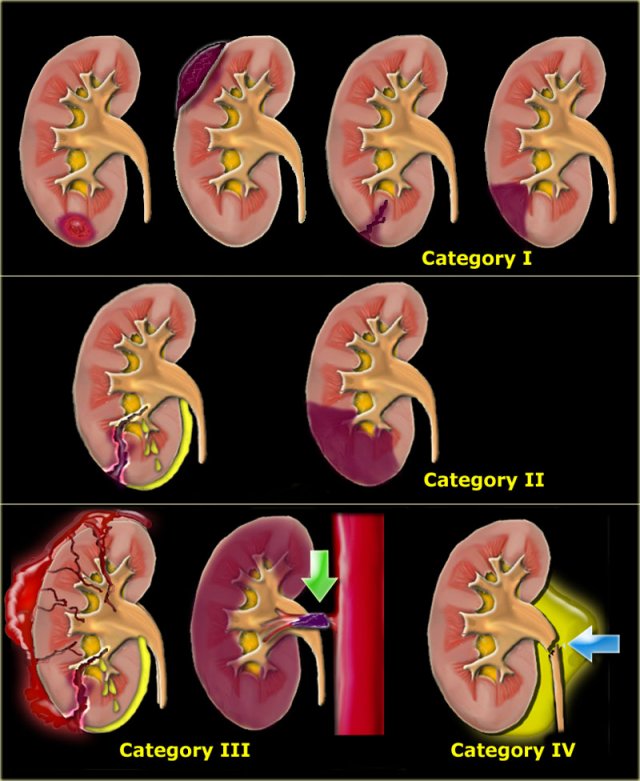

Michael Federle placed renal injuries into four categories:

-

Minor injury:

- renal contusion.

- intrarenal and subcapsular hematoma.

- minor laceration with limited perinephric hematoma without extension to the collecting system or medulla.

- small subsegmental infarct.

-

Major injury:

- major laceration into medulla or collecting system.

- segmental infarct.

-

Catastrophical injury:

- Maceration of the kidney

- Total devascularization due tot arterial occlusion.

- Rupture collecting system.

Bladder

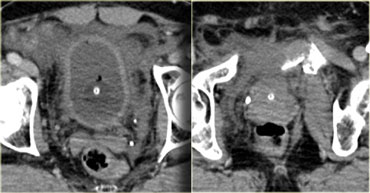

On the left a 65-year old male struck by a car traveling at moderate speed.

Loss of consciousness for 2 minutes.

A foley catheter was passed and there was gross hematuria.

The x-ray shows a moderately displaced fracture of the pubic bone with bony spicules in the bladder region.

So the question is:

For what other pelvic injuries is this patient at risk and how will it affect our protocol?

First this patient is at risk for arterial injury with pelvic hematoma, rectal, vaginal injury and bladder injury.

Secondly, a CT-cystogram is indicated after the routine CT.

On the left the images of the routine trauma-CT.

What are the findings?

There is a displaced pelvic fracture with a spicule pointing towards the bladder.

There is fluid in the prevesicle space (space of Rezius).

If there is a pelvic fracture the chance of a bladder rupture is 10%.

If there is a bladder rupture, there is almost always a pelvic fracture.

First it was thought that the rupture was caused by the pelvic fracture itself, but now we know that only in one third of cases the bladder rupture is at the site of the bone spicule.

Two third of rupture occur at the opposite site, meaning that shearing forces play a significant role in bladder injuries.

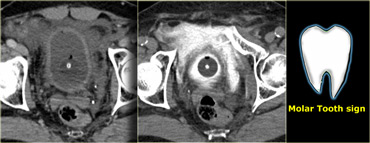

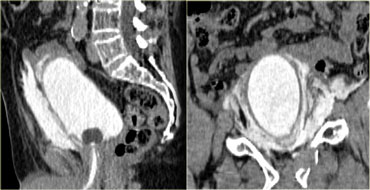

On the left the pre- and post-cystogram images.

There is contrast in the bladder surrounding the foley catheter and there is extravasation of contrast in the prevesicle space or space of Rezius.

This has been referred to as the 'molar tooth sign' indicating extraperitoneal bladder rupture.

On the left a sagittal and coronal reconstruction.

Notice that there is no contrast extending into the pericolic gutter, so there is no intraperitoneal extention.

The sensitivity and specificity of CT Cystography is very high.

For extraperitoneal rupture it is respectively 100% and 99% and for intraperitoneal rupture it is 92% and 100%.

The most important factor is that you have to have good distention of the bladder.

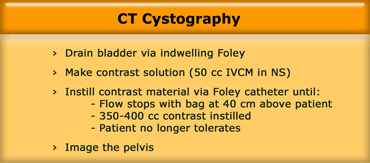

CT Cystography

First we drain the bladder, because we want to get rid of the urine and contrast that was excreted by the kidneys.

The contrast solution that we use is the same as we use for oral or rectal contrast (i.e. 50 cc contrast in 1L saline).

We instill the contrast retrograde through the foley catheter until one of three things happen:

- Flow stops with bag at 40 cm above the patient.

- 350-400 cc of contrast is instilled.

- Patient no longer tolerates.

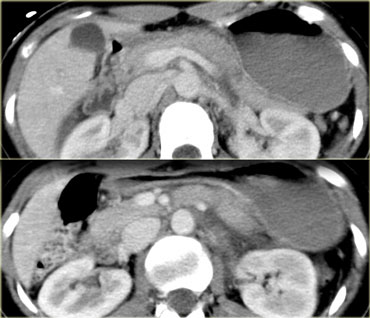

On the left another case to illustrate why you do not administer contrast in the bladder at the same time as the administration of iv. contrast.

The next question that comes up, is whether we should perform an additional CT-cystogram?

The answer to the first question is that if you would have administered contrast to the bladder at the start of the examination, you would have been puzzled whether the contrast that is seen is due to a bladder rupture or to active bleeding.

Since no contrast was instilled in the bladder, it is obvious, that this is arterial bleeding.

Secondly because of the enormous extravasation, this patient is in need of immediate embolisation without further delay.

Pancreas

Concerning pancreatic injury the following remarks can be made:

- Uncommon injury with a 0.4% overall incidence.

- 1.1% incidence in penetrating trauma and only 0.2% in blunt trauma.

- Rarely an isolated injury.

- Usually part of a 'package injury'.

On the left an unrestrained driver who had a car accident.

Vital signs were stable and there was only a mildly tender abdomen.

First look at the images on the left and then continue.

All the intraperitoneal organs were normal and there was no intraperitoneal fluid.

The only findings were a vague hypodense area in the pancreatic tail and some fluid behind the pancreas, best seen anteriorly to the left kidney.

So the radiologist said that there was concern about pancreatic injury.

The reason that he was not more definitive was that, an isolated pancreatic injury is exceptionally rare, since the pancreas is protected by the liver and spleen and the bony thorax.

During follow up this patient experienced more pain and on a follow up scan (not shown) there was impressive accumulation of fluid around the pancreas.

So this patient had an isolated pancreatic injury.

The case above is an exceptional case.

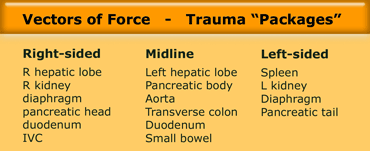

When the pancreas is involved in a trauma, it is almost always part of a package injury (Table).

The more common presentation of pancreatic injury is what is seen on the left.

Scroll through the images and describe the findings.

Then continue.

This is a typical left sided package injury.

There is pancreatic tail injury and also splenic injury, renal injury and pneumoperitoneum.

On the left another common presentation of pancreatic injury.

Look at the images and describe the findings.

Then continue.

There is a right sided package injury.

There is a liver laceration crossing the major vessels associated with a transsection of the pancreas at the junction of the head and the body.

The force must have come from the right anterior side squeezing the liver and the pancreas against the spine.

Sometimes this kind of injury also involves the duodenum.

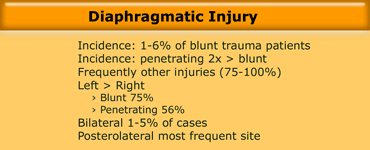

Diafragmatic injury

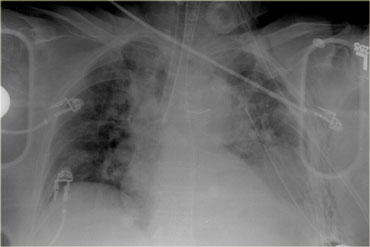

On the left a chest film of a 79-year old restrained driver who had a car accident.

Initially unresponsive at the scene.

He was transferred from an outside hospital after placement of tubes.

Look at the image on the left and describe the findings.

Then continue.

The first thing you'll notice is that the tube is in the right main bronchus.

Chest tube looks okay.

Nasogastric tube comes down and coils in the stomach.

The superior mediastinum looks widened and indistinct, so this certainly has to be evaluated.

In the left lower zone we have an indistinct diafragmatic border and an opacity.

This could be a lot of things like hematothorax, lung contusion, diafragmatic rupture or splenic injury.

So based on the chest film we are conceirned about possible aortic injury, pulmonary contusion and injury to the diaphragm, spleenic and left kidney.

Continue with the CT images.

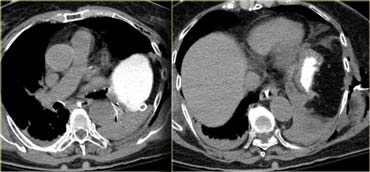

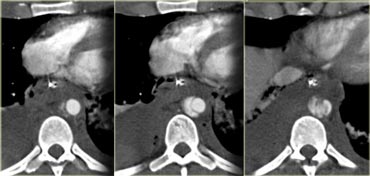

Scroll through the images on the left.

What contrast is on board adn wh at are the findings?

There is i.v. contrast in the late arterial phase and when we follow the nasogastric tube we will notice that there is no contrast in the stomach.

The most important finding in this case is the area of soft tissue density next to the atelectatic lower lobe of the lung and lateral to it an amount of fat.

This is very suggestive of diafragmatic rupture.

What can we do to get more certainty about this structure?

Since the nasogastric tube is in place, we can administer contrast to the stomach.

The images on the left prove that the structure is the stomach, which is in a high position.

Secondly there is a waist in the stomach compatible with the 'collar sign'.

These findings are specific for diafragmatic rupture.

CT 'collar' sign

On the left the coronal reconstruction of the same patient demonstrating the 'collar sign', where the stomach passes through the diafragmatic rupture.

So in the case above specific signs of diafragmatic injury are present.

Non-specific signs are discontinuity or thickening of the diafragm or the 'dependent viscera' sign.

'Dependent viscera' sign

On the left a demonstration of the 'dependent viscera' sign.

On the left side there clearly is a diafragmatic rupture with herniation of the stomach.

Notice that the stomach and the spleen lie against the posterior thoracic wall, which is abnormal.

This is unlike on the right side where the liver is away from the chest wall due to the presence of the diafragm.

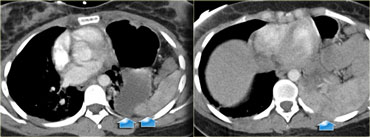

On the left a patient with a right-sided injury.

On the chest film it looks as if there is just elevation of the hemidiafragm or maybe there is a subpulmonic pleural fluid collection.

There also could be a baseline diafragmatic paralysis.

Now continue with the CT images.

Describe the findings on the left and then continue.

The axial image demonstrates that the opacity on the chest film is actually the liver.

As we follow the livercontour, there is this unusual shape (yellow arrow).

There is discontinuity of the crus which is a non-specific sign (small blue arrow).

On the axial image there is indentation of the liver on the posterior side due to blood in the thorax.

On the sagittal MPR there is indentation of the liver and the 'collar' sign is nicely demonstrated.

On the left some final remarks concerning diafragmatic rupture.

Aortic injury

On the left an unrestrained 22 y.o. male involved in a high-speed motor vehicle accident.

He was ejected from the vehicle.

At presentation he was unconscious and intubated with diminished femoral pulses.

Scroll through the images on the left and describe the findings.

The findings are:

- Pleural fluid with dependent high attenuation indicating hematothorax.

- Contrast blush near the spleen indicating active bleeding.

- Bilateral renal infarctions (additional images did show additional infarcts on the right side).

- Soft tissue density surrounding the aorta.

So the questions are:

- What are the diagnostic considerations?

- Does bilaterality of renal infarcts matter?

A unilateral renal infarct can be the result of a localized injury.

However when there are multiple bilateral infarcts, we have to think of an embolic source.

The most common location after injury for these emboli is in the thoracic aorta at the isthmus, because the aorta is fixated there.

In this patient however the source was a traumatic dissection of the aorta at the level of the diaphragm.

This is the second most common location for injury to the aorta due to the relative fixation.

.

Bowel injury

On the left images of a 44 y.o. male who jumped 40 feet from building onto concrete surface in suicide attempt.

History of treatment for depression

BP 90/54. Pale, diaphoretic, confused.

No head injury. Ecchymoses around chest and abdomen.

Distended abdomen. Pelvis grossly unstable.

Gross hematuria.

Scroll through the images on the left and describe the findings.

The findings are:

- Hypoperfusion of the spleen (yellow arrow).

- Multiple areas of contrast extravasation (green arrows).

- Hemoperitoneum and Pneumoperitoneum.

- Multiple segments of bowel with diffuse wall thickening (blue arrow).

The questions in this patient are:

- Is pneumoperitoneum diagnostic of full thickness bowel injury?

- What does the diffuse wall thickening of the small bowel suggest?

- Given vertical deceleration mechanism, where are bowel injuries most likely to occur?

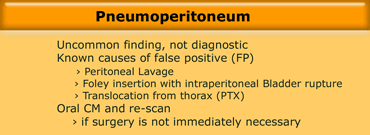

Concerning pneumoperitoneum some important remarks have to be made:

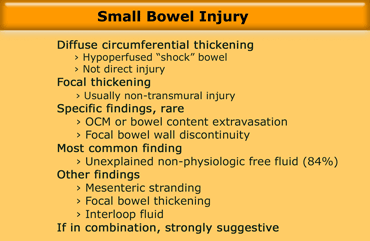

- When bowel injury is present, then pneumoperitoneum is an uncommon finding!

- When pneumoperitoneum is present, it is not diagnostic of bowel injury, since there are many false positives and air transmitted from the chest in pneumothorax is the most common cause of intraperitoneal air in a trauma patient (Table).

In fact the most common findings in small bowel injury are non-specific findings like thickening of the bowel wall and unexplained intraperitoneal fluid.

In the patient that we discussed the diffuse wall thickening was only a result of hypoperfusion or 'shock' bowel due to the active bleeding.

Direct injury to the bowel wall usually results in focal thickening and is mostly a non-transmural injury.

It is very uncommon to identify findings that are specific for bowel injury like extravasation of oral contrast or bowel content.

More commonly you will find a combination of intraperitoneal fluid and mesenteric stranding, focal bowel thickening or interloop fluid, that is very suggestive for bowel injury.