Appendicitis - US findings

by Julien Puylaert

Haaglanden Medical Centre in the Hague and Academical Medical Center in Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

In this article we will discuss the role of US in appendicitis and the additional role of CT scan.

The variable US features in the different stages of appendicitis will be dealt with, as well as the problem of spontaneously resolving appendicitis and the appendiceal abscess.

Pitfalls and differential diagnosis are discussed here.

For technique and normal anatomy: see “US of the GI tract”

For critical comments and additional remarks: j.puylaert@gmail.com

Introduction

Appendicitis is still the most common abdominal emergency in the Western world. There is a lifetime risk of 8 % to develop appendicitis, and yearly in the U.S.A 300.000 people undergo appendectomy.

The clinical diagnosis can be very difficult, and before the advent of US and CT, the negative appendectomy rate was around 30 %, while, on the other hand, initial delay of necessary surgery was also not uncommon.

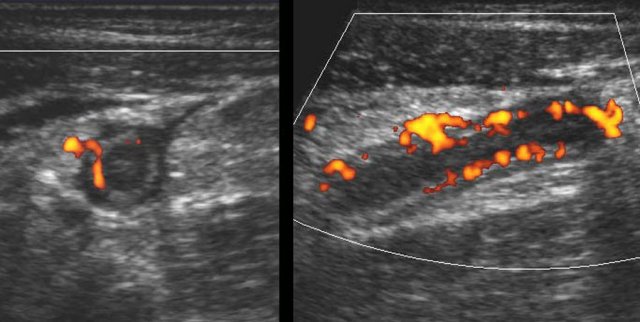

This US image shows an inflamed appendix in the axial (left) and longitudinal (right) view. This chapter on US for appendicitis is meant for all those actively involved in acute abdominal US.

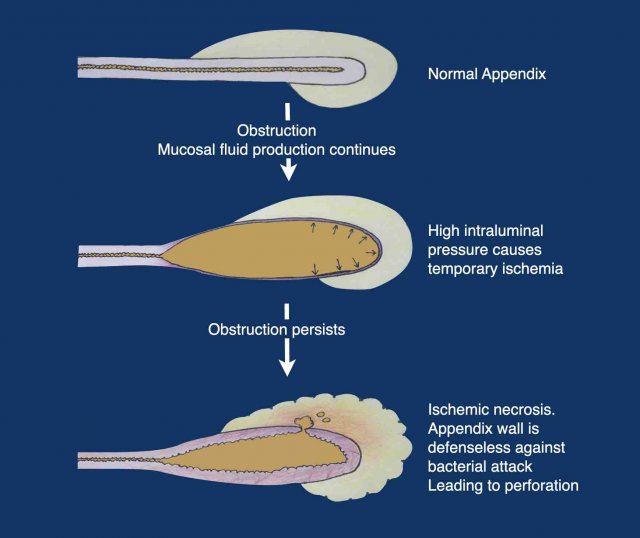

Pathophysiology of appendicitis

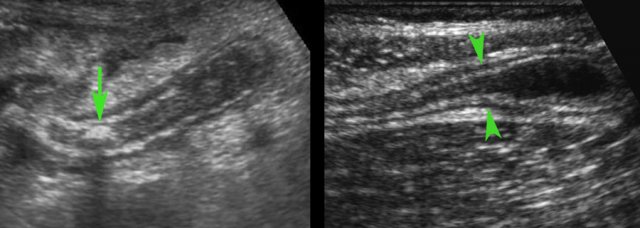

The appendix is a blind-ending tube with a narrow lumen.

It contains feces and is easily obstructed.

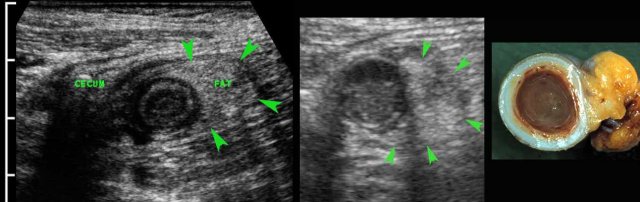

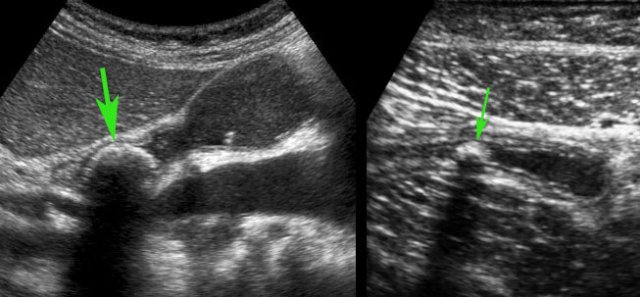

- In 35 % of cases a fecolith (arrow) is found at the level of obstruction.

- In 65 % there is no apparent cause for a mechanical obstruction found (arrowheads).

When obstruction occurs, within hours the intraluminal pressure increases, due to continuous secretion of mucinous fluid by the appendix mucosa.

When this pressure exceeds the pressure in the vessels of the appendix wall, ischemic necrosis may occur, leaving the mucosa defenseless against the bacteria present in the appendix lumen

Depending on the inflammatory reaction of the human defense mechanism, the pathophysiological cascade of obstruction - high pressure - ischemic necrosis - bacterial attack with perforation, results in a clinical presentation.

This has a wide variation ranging from mild, spontaneously resolving appendicitis to life threatening perforating appendicitis, and everything in-between.

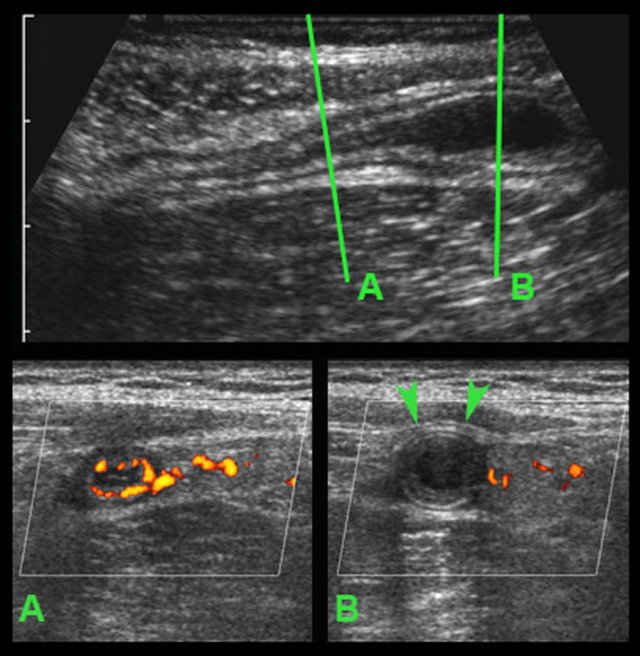

In this very lean patient with early acute appendicitis, US reveals dilatation of the distal appendix.

In plane A, Doppler US shows strong hypervascularization of the wall, however in plane B no vessels are visible in the appendix wall due to high intraluminal pressure.

Note the dilated, non-compressible, round appendix in B, bulging into the abdominal wall during compression (arrowheads), with only vascularization in the fatty meso-appendix.

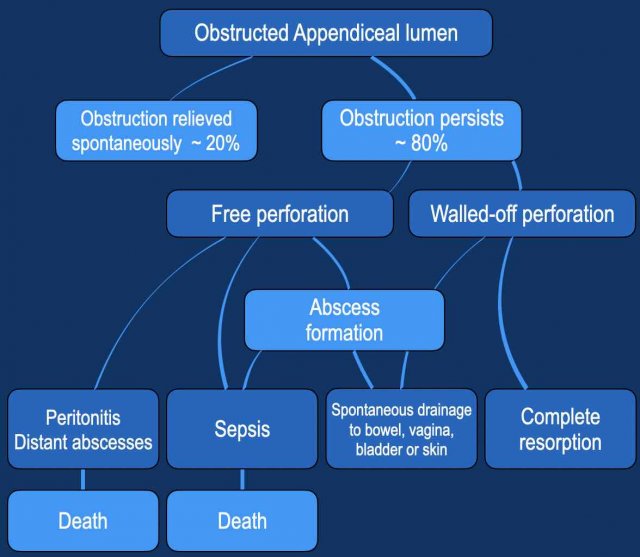

The natural course of untreated appendicitis is reflected in this table.

Exact mortality rates in the era before surgery and antibiotics are unknown, but were probably around 10 - 20 %.

Nowadays, mortality due to appendicitis has decreased to around 0,1 % , mainly due to early surgery, antibiotics and better diagnosis: US, CT, MRI and also the important lab value CRP.

Note that in about one in five cases, appendiceal obstruction is relieved in an early phase.

This results in spontaneously resolving appendicitis, which entity will be discussed later.

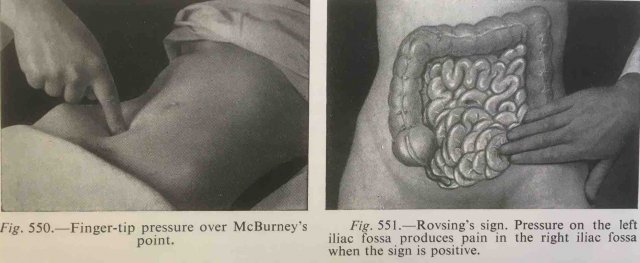

Clinical signs of appendicitis

The classic clinical signs of appendicitis are (sub)acute abdominal pain, starting in the epigastric or periumbilical area (= visceral pain-phase).

After 4 to 6 hours shifting towards the right lower quadrant (RLQ), where local peritonitis develops.However symptoms can be very atypical and treacherous, and the only constant sign is acute or subacute abdominal pain.

The clinical diagnosis of appendicitis is difficult, and is often wrongly made and initially overlooked, leading to unnecessary surgery respectively to ill-advised delay.

Before US and CT, the negative appendectomy rate reported in the literature was 28 % (Pieper R. Acta Chir Scand 1982;148: 51-62) while in-hospital delay occurred in about 20 %. US and CT as well as the use of CRP, have brought down both numbers to around 5 %.

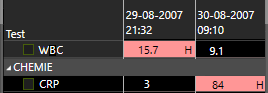

The role of lab findings

In the diagnosis of appendicitis the most valuable lab findings are WBC (White Bloodcell Count) and CRP (C- Reactive Protein).

In early acute appendicitis, the WBC rapidly increases within a few hours and often returns to normal after 12 - 24 hours.

The CRP remains normal during the first 6-12 hours, and then increases, with values that -dependent of the inflammatory reaction- vary from 30 to 500 (mg/l).

In a patient with > 24 hours of symptoms and a normal CRP, the chance for appendicitis is very low.

The only exception is spontaneous resolving appendicitis. Careful matching patient’s history, lab and US findings is key.

Other laboratory values are mainly valuable in the differential diagnosis of appendicitis.

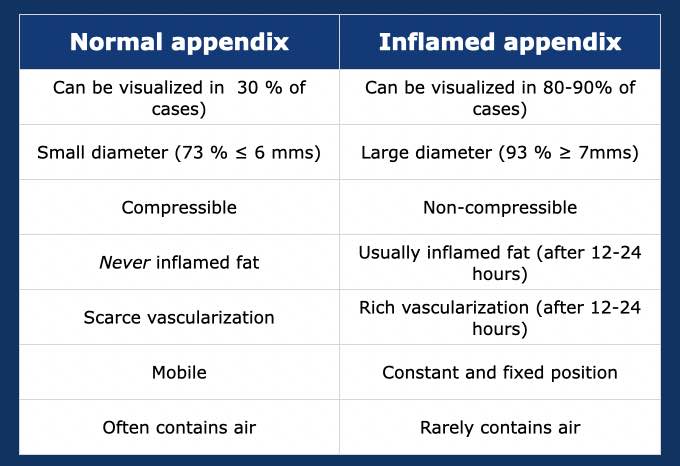

US of normal vs inflamed appendix

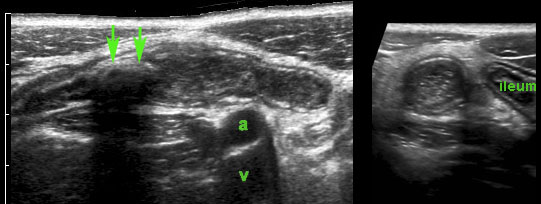

The US features of the normal appendix are discussed in “US of the GI tract: normal anatomy”. Differentiating an inflamed appendix from a normal one is quite easy in most cases.

Normal appendix – can be visualized in 20-30 % of cases.

Inflamed appendix - can be visualized in 80-90 % of cases.

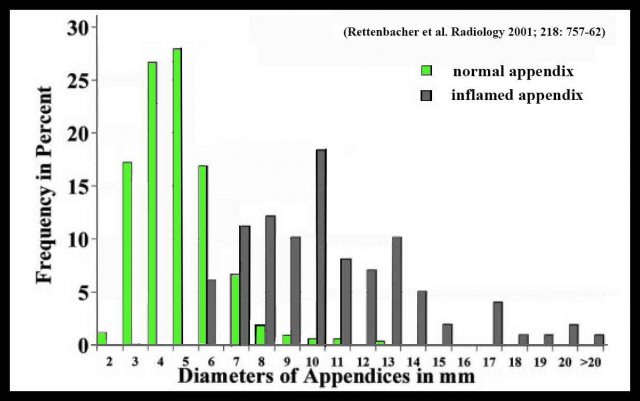

There is overlap between the diameter of the normal and inflamed appendix:

- Cut-off point of ≥ 7 mms - 7 % of appendices is normal.

- Cut-off point of ≥ 6 mms - 27 % of appendices is normal.

The appendix diameter of normal and inflamed appendices on CT shows even a greater overlap.

The explanation for this phenomenon is described in “US of the GI tract: normal anatomy”.

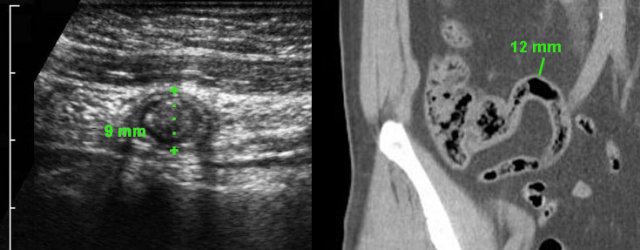

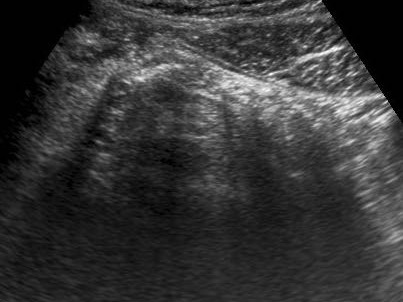

Two asymptomatic individuals with large, feces-filled but non-inflamed appendices demonstrated by US and CT scan.

Note complete absence of inflamed fat in both.

US of appendicitis

Appendicitis with intraluminal fecolith (arrows) is found at the level of obstruction (a and v = iliac artery and vein).

Appendicitis with intraluminal fecolith (arrows) is found at the level of obstruction (a and v = iliac artery and vein).

The typical appearance of an inflamed appendix:

- aperistaltic

- concentrically layered

- non-compressible

- blind-ending

- sausage-like structure

- in a constant position, usually at the site of maximum tenderness

- the average maximum diameter is 11 mms (variation from 6 to 25 mms

- in 35% an intraluminal fecolith (arrows) is found at the level of obstruction

In the first 6-12 hours the lumen of the appendix is strongly dilated with a thin wall and there is no inflamed fat yet.

This patient presented with severe, acute periumbilical pain since 4 hours and had no localized pain over the dilated appendix. (visceral pain-phase).

Note the bulging of the tense appendix in the abdominal wall (arrowheads) during compression.

These appendices are easily overlooked during US examination, due to the absence of circumscribed local pain ánd due to the absence of inflamed fat.

Moreover, these patients are often sent home without US or CT, because their visceral pain symptoms are interpreted and treated as “stomach or gallbladder problems”.

Inflamed fat

The fatty tissue that is first involved in appendicitis, is the mesentery of the appendix or meso-appendix.

The normal fatty meso-appendix can be identified if outlined by some intraperitoneal fluid as in this patient, and is moderately hyperechoic, soft and well-compressible.

Roughly 4-6 hours after the onset of symptoms, the inflammation begins to affect the meso-appendix, which becomes larger, more hyperechoic and non-compressible (arrowheads).

The ensuing fibrin production on the serosal surface causes local peritonitis, resulting in the well-known shift of pain from the periumbilical or epigastric area to the right lower quadrant.

Interestingly, in the early stages of inflamed fat, US is more sensitive than CT scan.

In this patient with RLQ pain since 18 hours, CT showed only minimal fatty stranding around an 8.5 mm appendix (arrow).

US with graded compression already shows unmistakable, non-compressible, hyperechoic, inflamed fat (arrowheads) around the appendix.

Later on in the disease process, this fatty tissue around the appendix tends to increase in volume.

This represents the fatty omentum, which has migrated towards the appendix in an attempt to wall-off the imminent perforation.

Slowly applied intermittent compression is the best way to identify the non-compressible inflamed fat.

Compression of the ventrally located bowel loop also reduces the negative influence of gas.

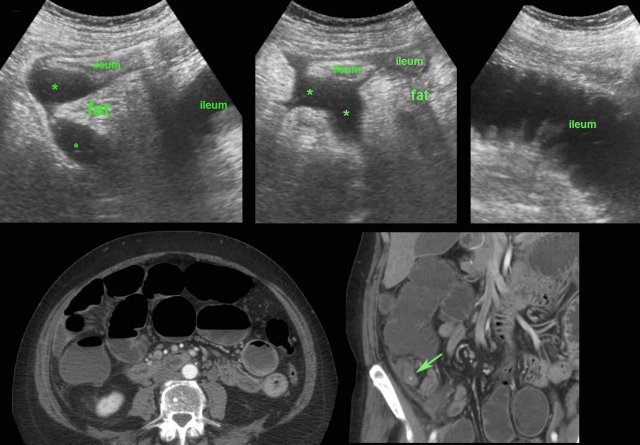

Eventually, also neighboring bowel and its mesentery become involved in the walling-off process.

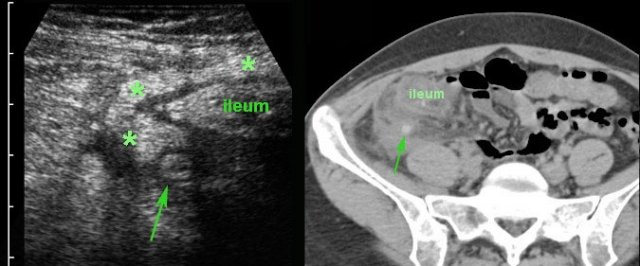

In this patient, US shows large quantities of inflamed fat (*) and the thickened ileum representing successful walling-off of the (imminent) perforation of the appendix (arrow).

Note a calcified fecolith (arrow on CT scan) in the appendix at a higher level.

The longer this process of “walling-off” is going on, the more difficult appendectomy is going to be.

This dilemma is discussed in the chapter “appendiceal mass”.

Layer structure

An irregular, asymmetrical echolucent contour and loss of wall layer structure indicate perforation or imminent perforation of the appendix.

In this stage there is always abundant inflamed fat (arrowheads).

The more the layer structure is affected, the higher the chance for perforation.

The first sign being echolucent changes in the hyperechoic submucosa.

Predicting of perforation based on the US image is not very reliable but has little therapeutic consequences at that moment.

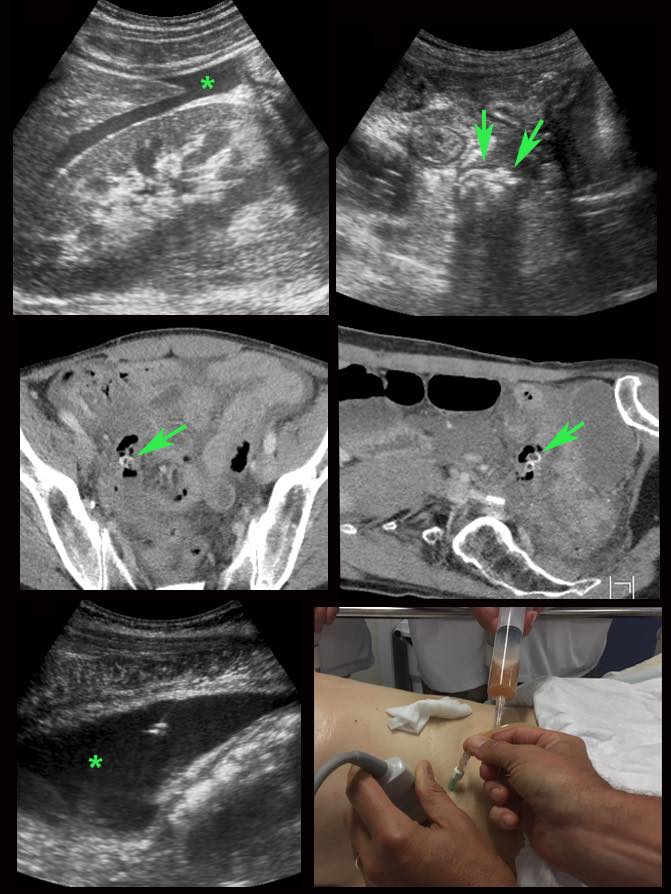

Free fluid

A little echolucent intra-peritoneal fluid (*) has little meaning and can be found in both acute, non-perforated appendicitis (left) and perforated appendicitis (arrow) (middle), but also in patients with a normal appendix (right).

Larger quantities of fluid, especially if circumscribed and/or turbid, often accompanied by local or generalized paralytic ileus are suspect for perforation.

Usually these patients are ill, painful and have a high CRP.

In this 56-year old lady with a CRP of 180, US revealed turbid intraperitoneal fluid (*) and possibly an inflamed appendix with fecoliths (arrows).

CT confirmed two fecoliths in the RLQ with odd air-configurations, suspect for perforated appendicitis.

US guided puncture confirmed purulent fluid.

Immediate surgery revealed perforated appendicitis with four quadrant contamination of the abdominal cavity with pus.

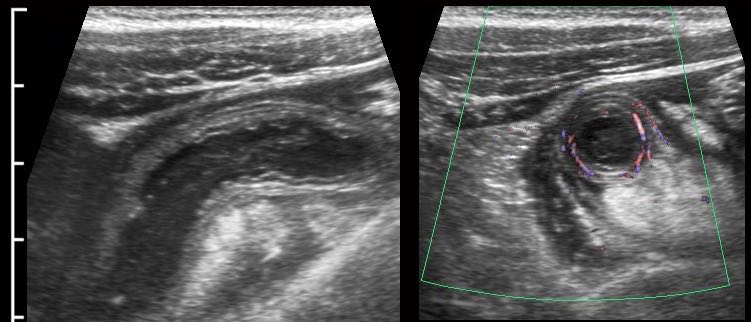

Hypervascularization

As shown earlier, the vascularization of the appendix wall is initially decreased due to high intraluminal pressure.

However, this high pressure will drop again rapidly since the diseased appendix mucosa is not able to maintain its normal fluid production anymore.

As a result, in combination with the massive inflammatory response , strong reactive hypervascularization will occur rapidly: first in the surrounding fatty tissue and, soon after, also within the appendix wall.

Since this is the point in time, where patients usually seek medical help, this is the most familiar US image of the inflamed appendix.

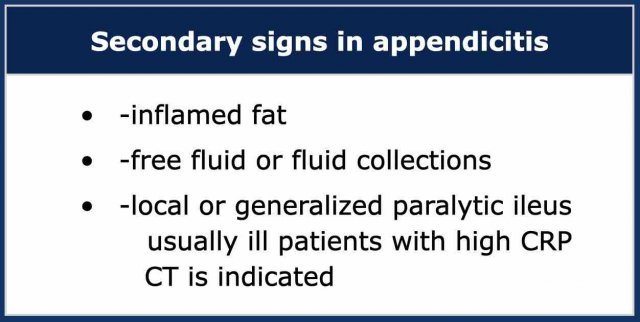

Secondary signs of appendicitis

In patients in whom the appendix cannot be visualized by US and also no alternative condition can be found, secondary signs of appendicitis may be helpful.

In this ill and painful patient the only US findings were a generalized paralytic ileus and a little turbid free fluid (*).

Note that the only movement of the bowel is from in- and expiration.

Subsequent CT and surgery confirmed purulent peritonitis from perforated appendicitis.

This was an ill, 67-year old woman, CRP 310.

US showed a combination of thickened ileal loops, paralytic ileus, inflamed fat and ill-defined fluidcollections (*), but no inflamed appendix or other cause of bowel perforation.

CT confirmed paralytic ileus and an inflamed appendix (arrow).

Surgery revealed severely contaminated purulent peritonitis from perforated appendicitis.

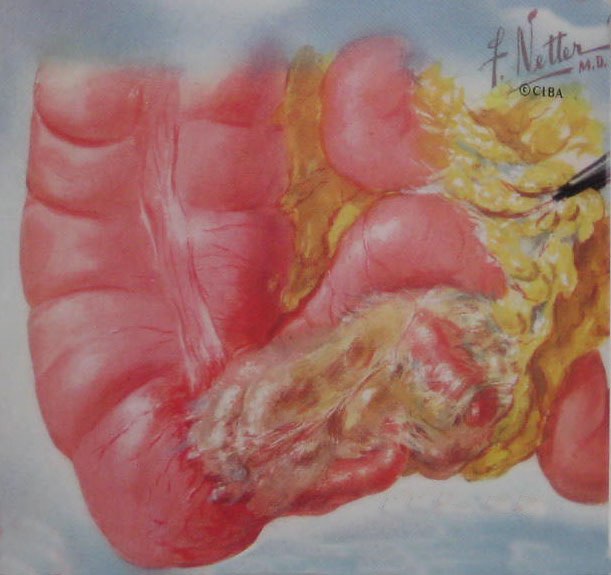

The “appendiceal mass”

Not infrequently, patients seek medical help (or are admitted) with considerable delay (> 4-5 days).

These patients often present with a palpable mass and relatively mild peritonitis.

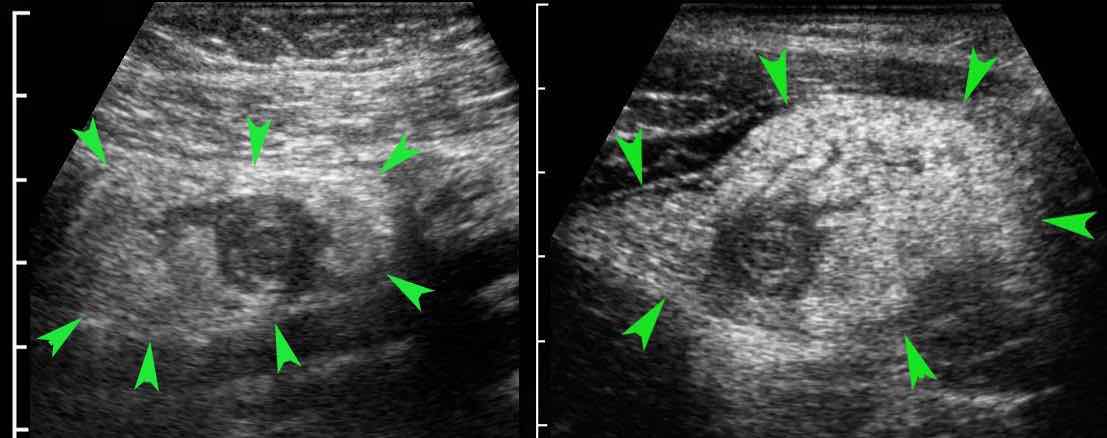

US and CT often show a large mass of non-compressible fat around the appendix, often also with wall thickening of neighboring bowel loops.

If there is a circumscribed pus collection, the diagnosis is appendiceal abscess. If not, the diagnosis is appendiceal phlegmon.

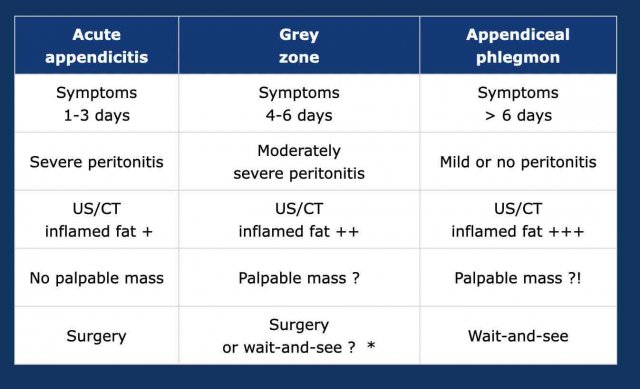

Appendiceal phlegmon

Patients with an appendiceal phlegmon are usually managed conservatively because the surgeon knows from experience that appendectomy in such cases is technically difficult or even impossible.

The problem with the diagnosis of an appendiceal phlegmon is that there is large “grey zone” where the surgeon may not be sure whether to operate immediately or whether to opt for conservative management.

This is understandable since there is a gradual evolution from acute appendicitis to an appendiceal phlegmon.

In the decision between surgery and wait-and-see, in general the clinical symptoms prevail over the US and CT findings.

A walled-off pus-collection within the appendiceal phlegmon, is usually a contra indication for immediate surgery.

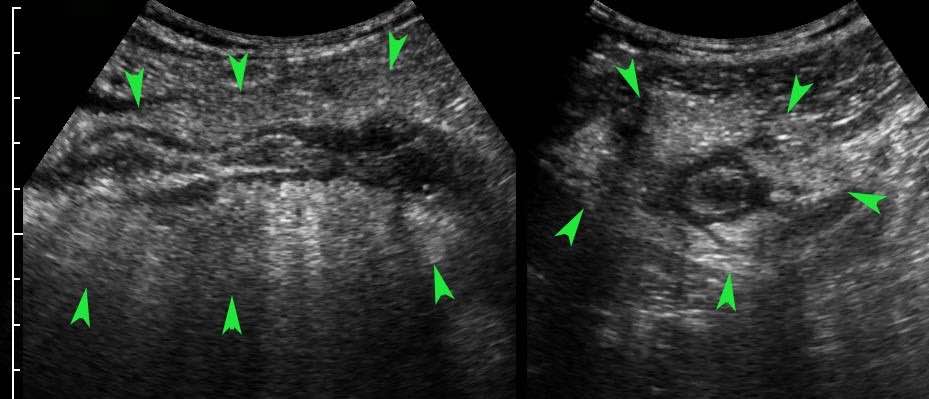

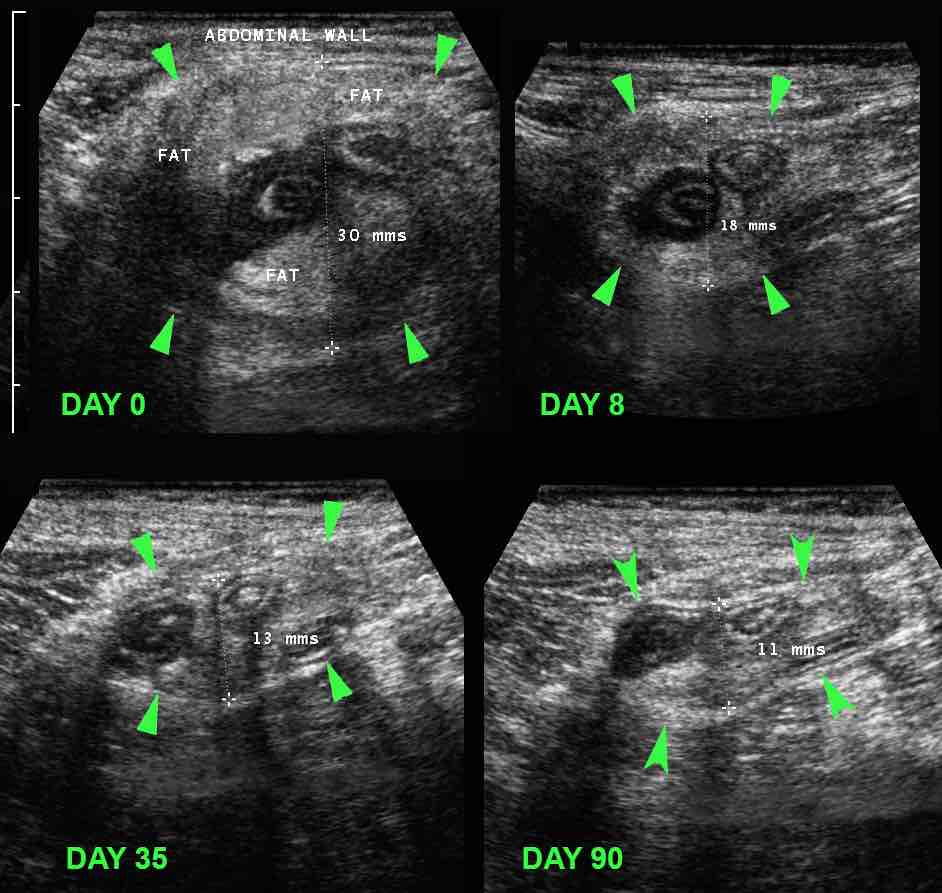

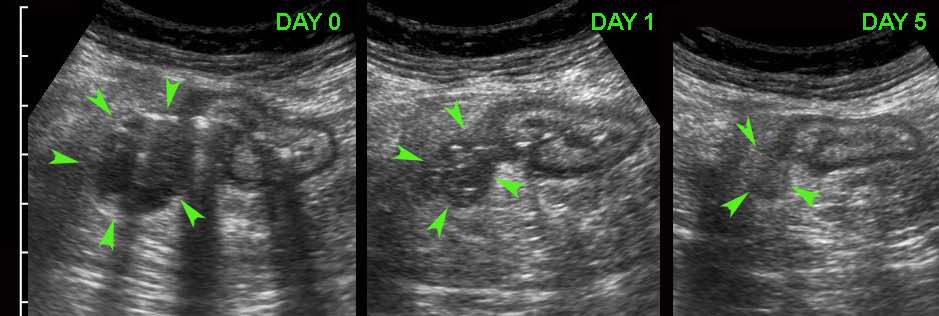

If conservative treatment of an appendiceal phlegmon is successful, follow up US shows a decrease in size of the periappendiceal mass (arrowheads) within the course of weeks to months.

This patient was already symptom free from week three.

US allows rough objectification of the palpable mass (arrowheads) around the inflamed appendix, and can be used in follow-up.

This also makes underlying malignancy unlikely.

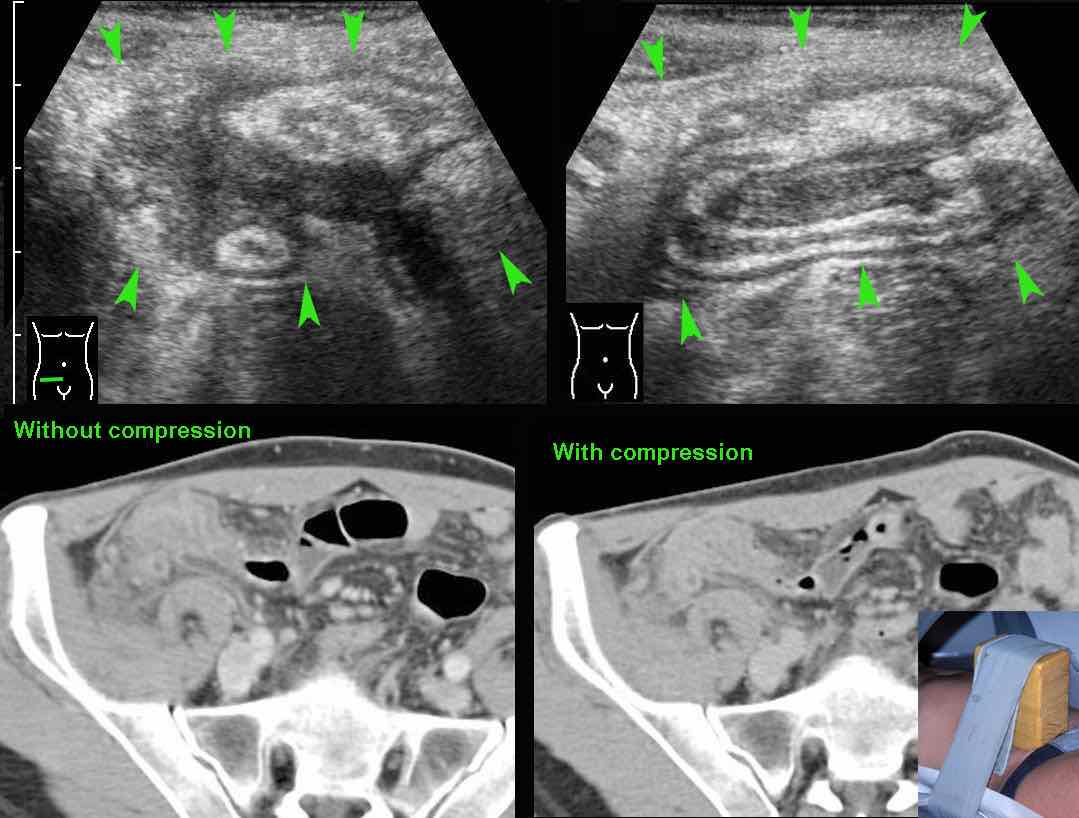

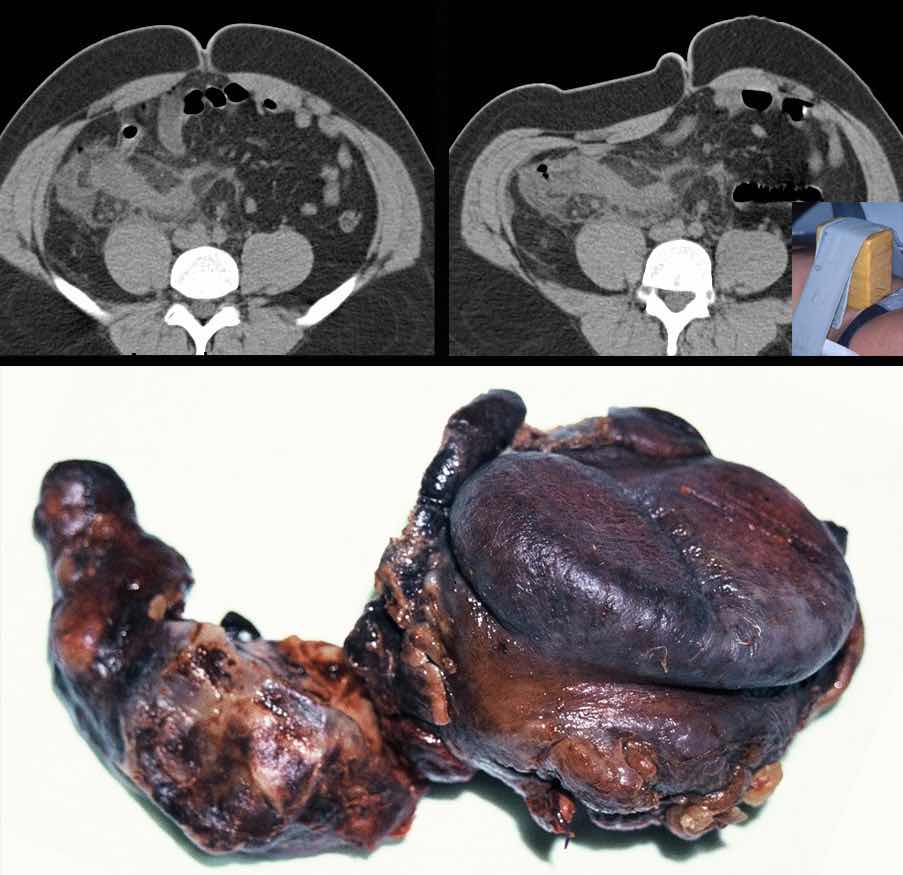

One of the advantages of US over CT, is that using graded compression, US can estimate the dimensions of the “palpable” inflammatory mass (arrowheads) around the inflamed appendix.

If necessary, compressibility can also be tested on CT scan, with the help of a wooden device, strapped to the abdomen of the patient (see insert).

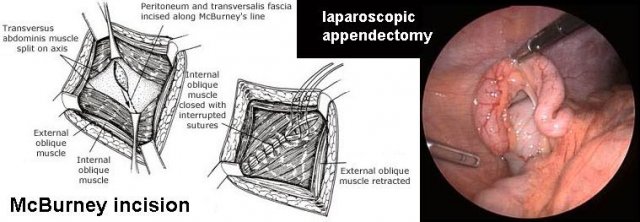

This obese patient with advanced appendicitis and symptoms for eight days, CT with compression demonstrated a large, non-compressible inflammatory mass around the appendix. Nevertheless, the patient was immediately operated, based on clinical grounds. During operation the McBurney incision was extended at both ends, and an ileocecal resection eventually was performed.

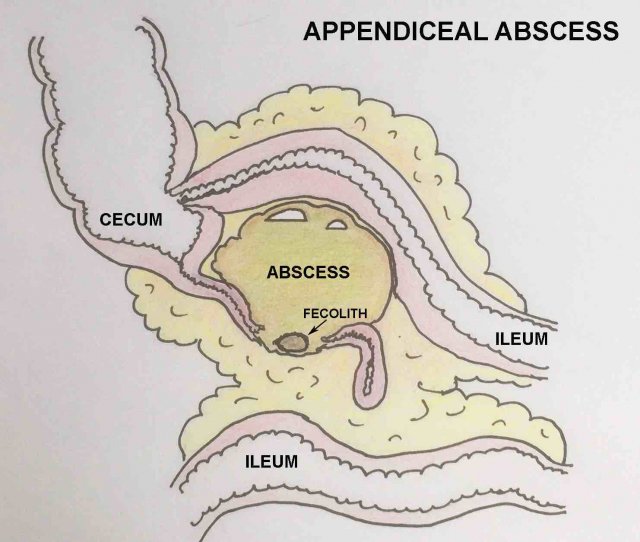

Appendiceal abscess

If next to the inflamed appendix, a more or less circumscribed fluid collection is found, this is suggestive for an appendiceal abscess.

The collection often contains air, not infrequently (~50 %) a fecolith and is surrounded by inflamed non-compressible fatty tissue.

The latter not only represents the omentum (“policeman of the belly”) but also the fatty epiploic appendages and fatty mesentery.

Together with neighboring bowel loops, this represents the -often successful- walling-off of the appendiceal abscess in attempt to prevent spill of pus to the peritoneal cavity.

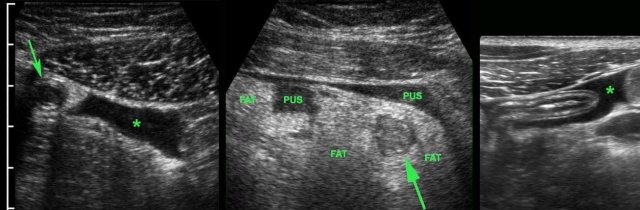

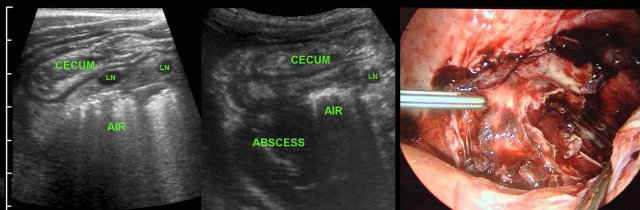

Patient with a small appendiceal abscess, ventrally walled-off by the ileum.

The appendix (arrows) is small because it has evacuated its purulent contents in to the abscess.

Note the calcified fecolith (arrowhead) on the bottom of the abscess.

Drainage was performed from laterally.

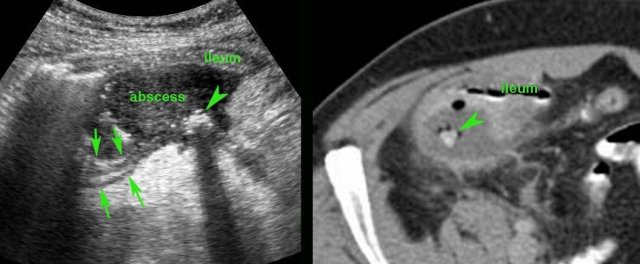

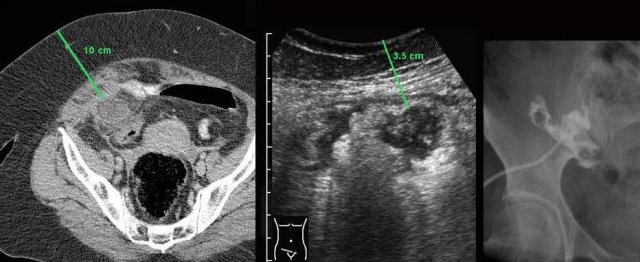

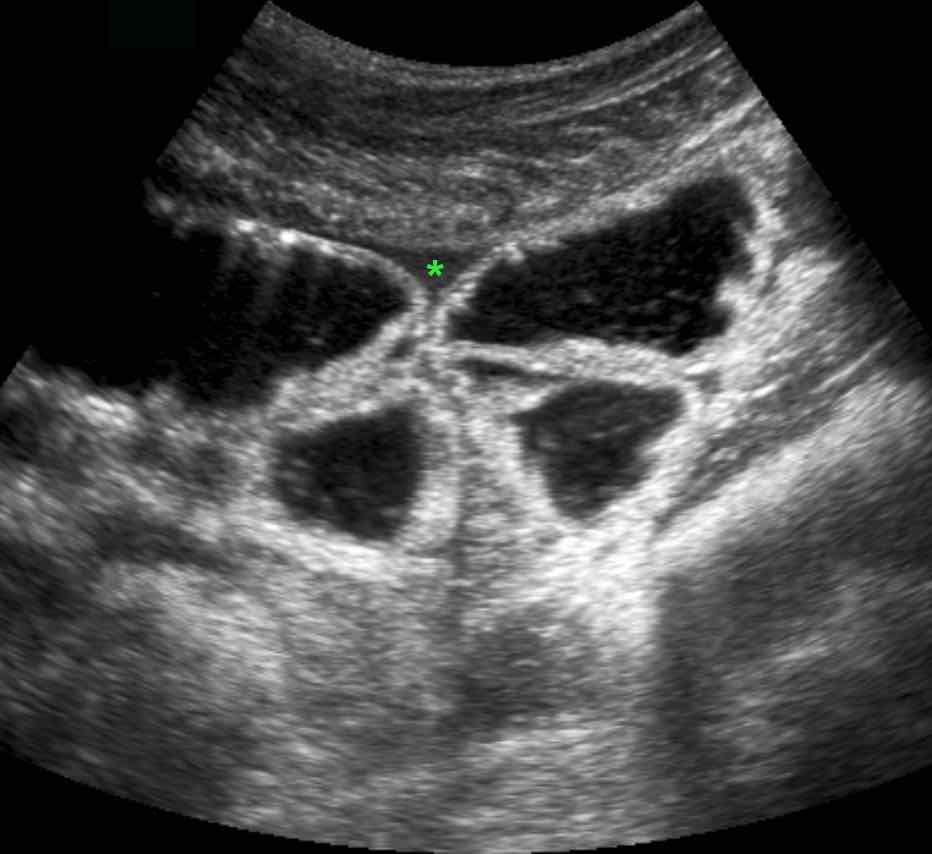

Man of 70 years, with a large abscess in the RLQ.

On CT the appendix could not be identified.

US confirms an inflamed appendix (arrow).

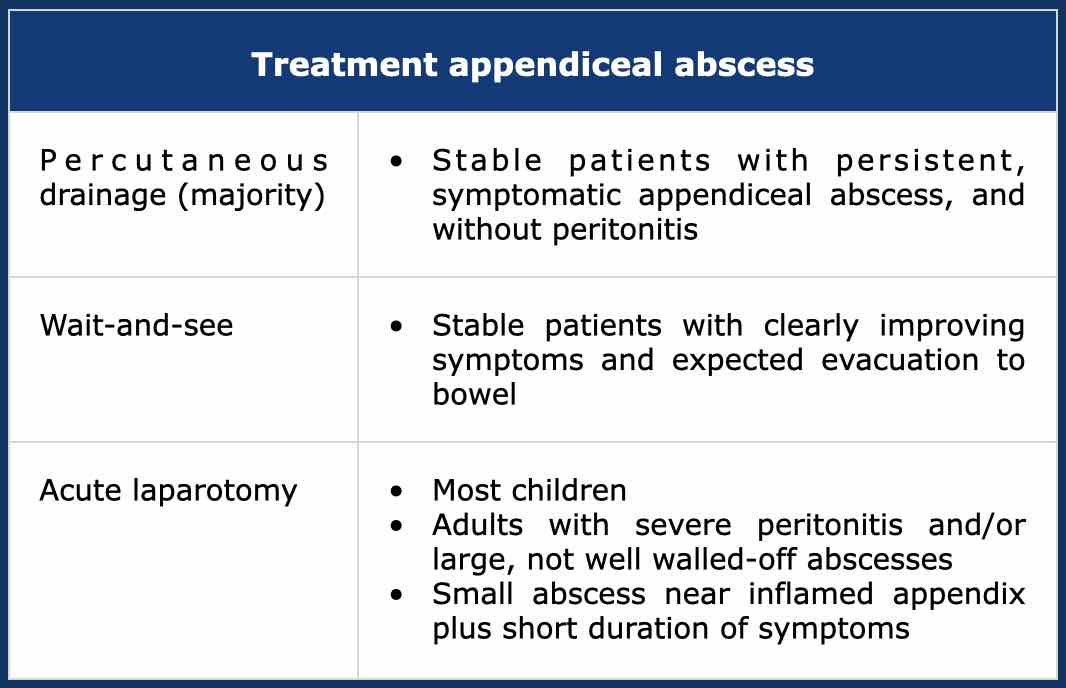

If an appendiceal abscess is demonstrated and there is absent or only mild peritonitis, percutaneous drainage is the treatment of choice.

Dependent of symptoms and US/CT findings, acute laparotomy and wait-and-see are also options.

In the majority of patients with an appendiceal abscess, percutaneous drainage is the treatment of choice.

CT is necessary to confirm the diagnosis, to delineate the extent of the abscess and to determine a safe access route.

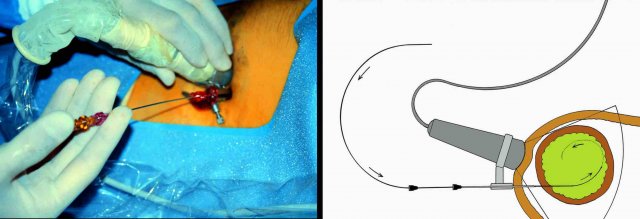

Drainage using a combination of US and fluoroscopy has several advantages over CT guided drainage: it is rapid, allows continuous control, any angulation and the use of compression during the procedure.

This patient had a large appendiceal abscess, walled-off by ileum and cecum.

A small window (arrow) allowed US-guided puncture.

Insertion of the drain over a guidewire was done under fluoroscopic control.

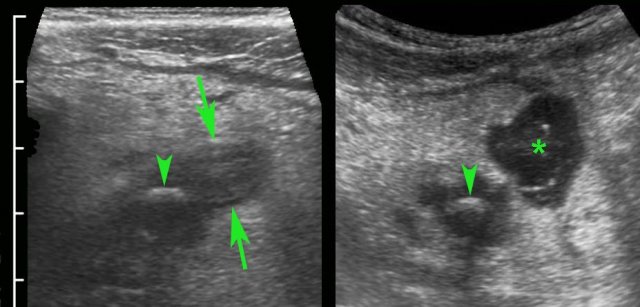

In this obese patient, drainage with the US probe using compression, allows the needle to approach the abscess closely.

Note that compression here reduced the distance skin-to-abscess from10 to 3.5 cm.

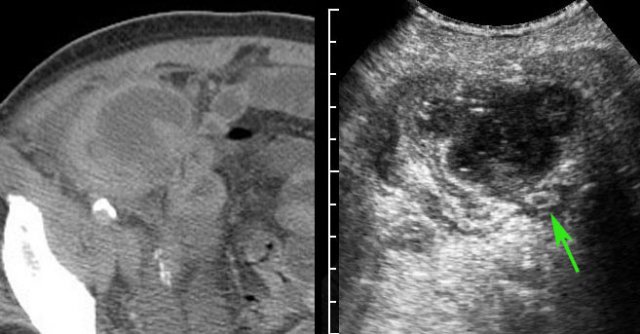

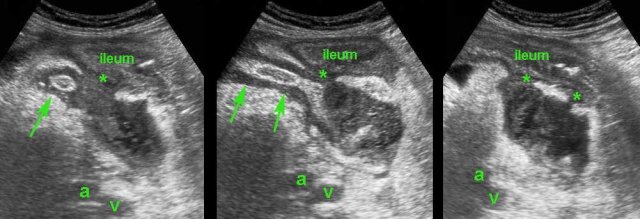

In stable patients who have no fever and only mild pain, it may be wise to await spontaneous drainage of the abscess to neighboring bowel.

This 75-year old lady had subsiding symptoms after 7 days of RLQ pain, and she told us that she was feeling much better now.

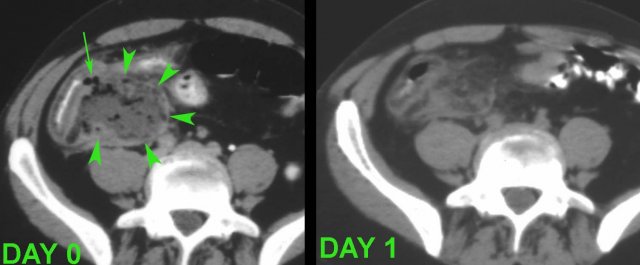

US showed an inflamed appendix (arrow) with an adjacent abscess, walled-off by inflamed fat and the terminal ileum.

There were echolucent connections (*) between the abscess and the ileum, indicating spontaneous evacuation (a and v = right iliac artery and vein).

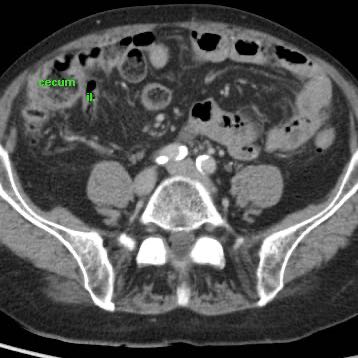

CT scan confirmed the anatomic situation.

The patient was completely cured with only antibiotics.

Three years later she underwent CT for sigmoid diverticulitis which allowed us to take a look at her appendix region.

The appendix (arrows) was small and still had intimate contact with the ileum (il.)

Another 4 years later, at age 82, she is still doing fine.

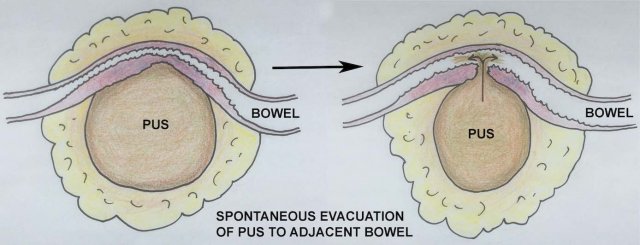

The process of spontaneous evacuation of a puscollection to neighboring bowel can be followed by doing repeated US.

At the time of US, this patient with a large appendiceal abscess (arrowheads) was feeling much better and refused drainage.

The next day he was almost symptom free after an episode with remarkably smelly stool.

In hindsight two air bubbles (arrow) indicated impending evacuation of the pus to the cecal lumen.

Spontaneous evacuation of a pus collection to neighboring bowel is nature’s most efficient way to get rid of an abscess or empyema.

Other pathways (e.g. to the abdominal wall, to the vagina or to the bladder) are slower and may result in fistula formation.

Douglas abscesses, usually evacuate itself to the rectum.

If not, transrectal or transgluteal drainage is indicated.

In this patient with a Douglas abscess the surgeon planned transrectal drainage on the OR, but was not able to locate the abscess.

CT-guided transgluteal drainage under local anesthesia was successful.

Some patients with an “appendiceal abscess” are better off with immediate surgery.

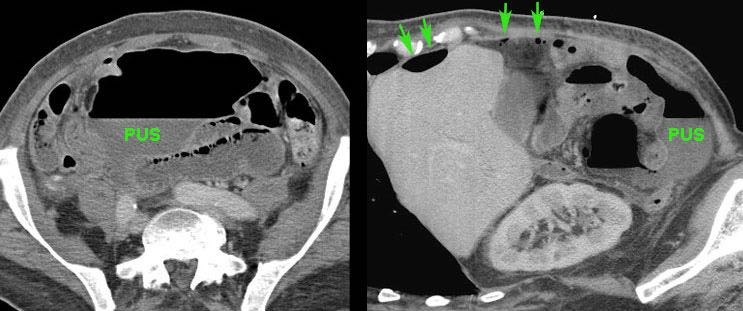

These two patients were both ill with a high CRP and signs of generalized peritonitis.

US and CT confirmed paralytic ileus and large, not-well walled-off air-fluid collections, and in the right patient some free air (arrows).

These combined clinical and CT findings indicate a failing defense mechanism, warranting surgery.

Children often present with free perforated appendicitis, because the disease progresses more rapidly and abscess formation is less effective than in adults.

Children with an appendiceal abscess usually undergo surgery.

In this 11 year old girl with a ten days old large retrocecal abscess, both drainage and appendectomy was easily performed laparoscopically.

Finally, in patients with a small (< 2 cm) abscess (*) close to the appendix (arrows) who have only 3-4 days of symptoms, immediate appendectomy with removal of the small abscess is a good option.

Note the fecolith (arrowhead)

In difficult cases where the anatomical situation in a patient with an acute abdomen is rather complex, communication with the surgeon is crucial.

Rather than “label” a diagnosis in the US/CT report, it is better to discuss the US/CT findings together with the surgeon before the monitor.

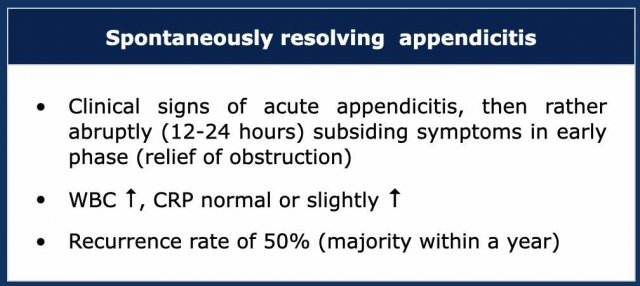

Spontaneously resolving appendicitis

About one in ten patients with acute appendicitis mentions one or more episodes of the same symptoms over the past months or years, which symptoms at that point in time spontaneously subsided within a period of 12-24 hours.

Laboratory shows an elevated WBC and no or only mildly elevated CRP.

The increasing use of US and CT in patients with RLQ pain has learned that this phenomenon of so-called “spontaneously resolving appendicitis” is not rare.

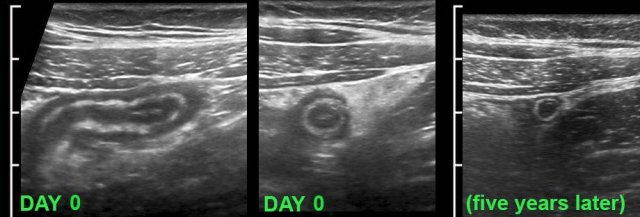

This young lady had typical signs of appendicitis for 24 hours (WBC 12 ,CRP 2).

US showed an inflamed appendix.

Within a period of hours her symptoms rapidly decreased and she was not operated.

US was performed 5 years later for other reasons and demonstrated a normal appendix.

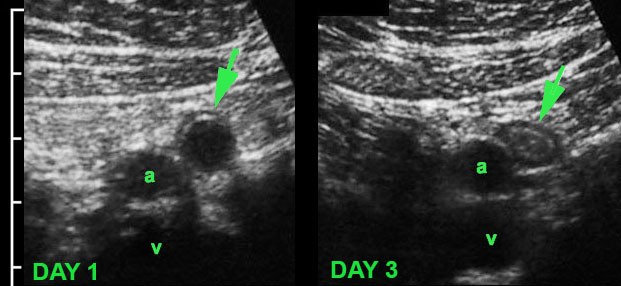

In this patient, the appendix (arrow) on admission showed a dilated lumen and minimal surrounding fat. After the US examination the patient had rapidly subsiding symptoms and was not operated. Three days later he was symptom free and US showed a compressible appendix (arrow) with a slightly thickened wall and a collapsed lumen and surrounded by some inflamed fat. These images, the rather sudden resolution of symptoms and the usually low CRP, suggest that the cause of this phenomenon is relief of luminal obstruction at an early stage.

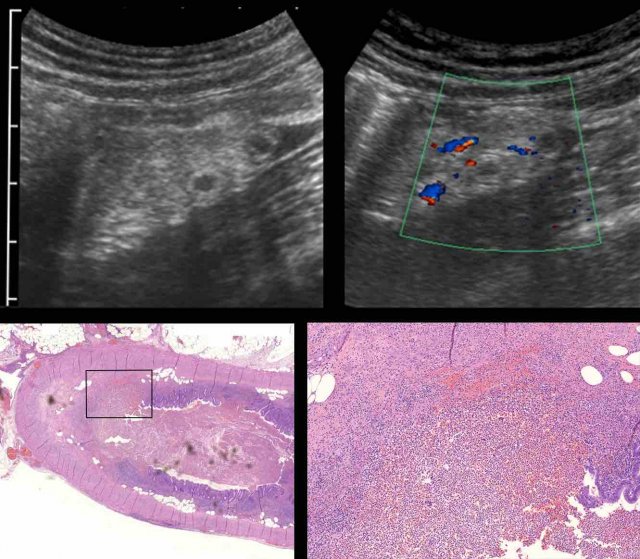

This patient had a classic history of appendicitis but was symptom free again at the time of US. US showed a small appendix (arrows) of 6 mm, surrounded by hyperemic, non-compressible, inflamed fat. He recalled three similar attacks over the past 9 months, and was operated immediately. Surgical and histological findings confirmed acute inflammation, with transmural infiltration with granulocytes.

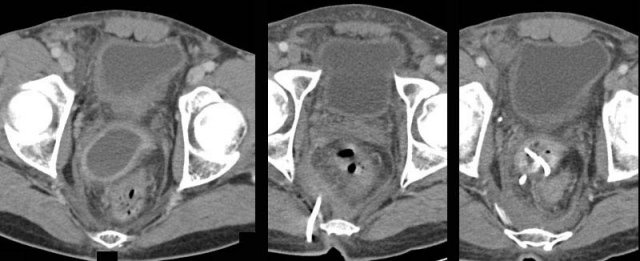

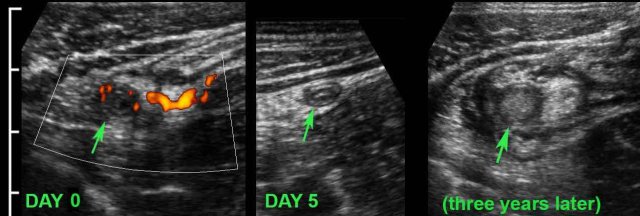

This young woman had pain in the RLQ for 24 hours (WBC 12, CRP 34), when she noticed rapid resolution of symptoms.

US showed a small 6.5 mm hyperemic appendix (arrow), surrounded by inflamed fat.

She was not operated and was symptom free the next day.

US after 5 days showed normalization of the appendix (arrow).

Three years later, she had recurrent symptoms and US showed acute appendicitis.

Surgery revealed perforated appendicitis.

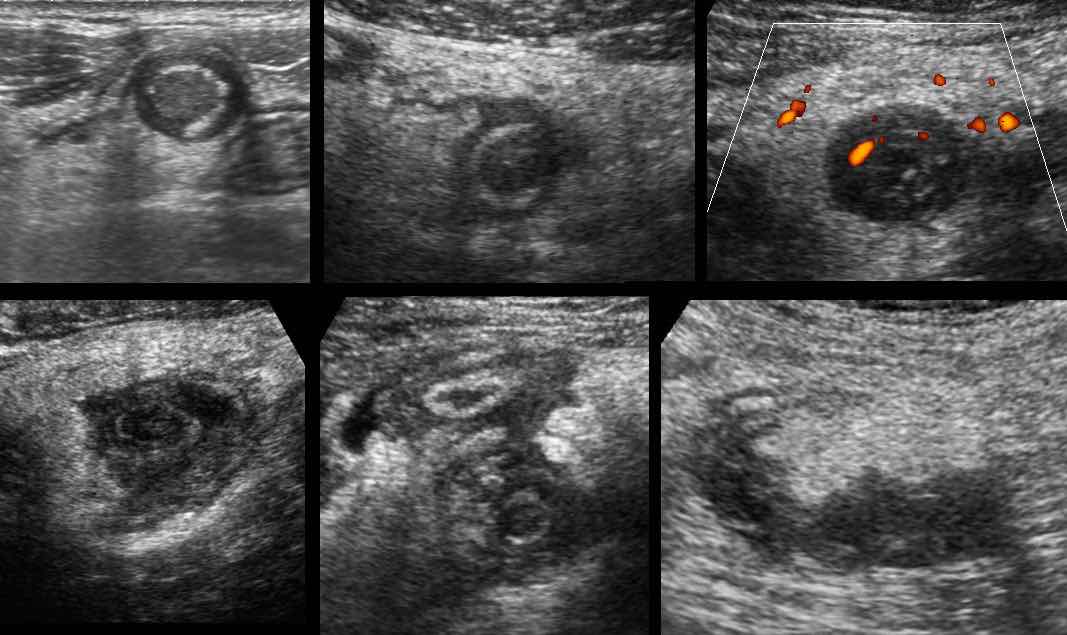

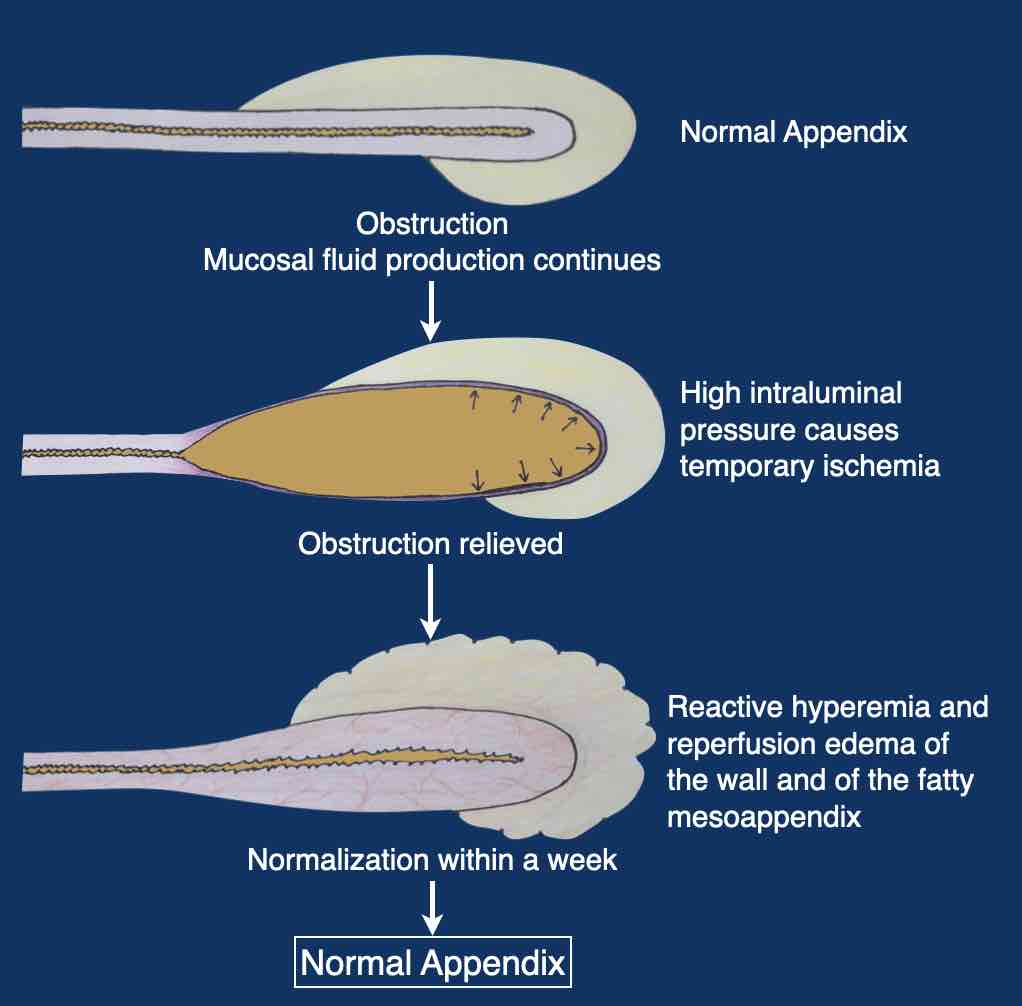

Here the different stages of spontaneously resolving appendicitis are schematically represented.

By the time patients with spontaneous resolving appendicitis undergo US, most are then in the stage of reactive hyperemia and reperfusion edema.

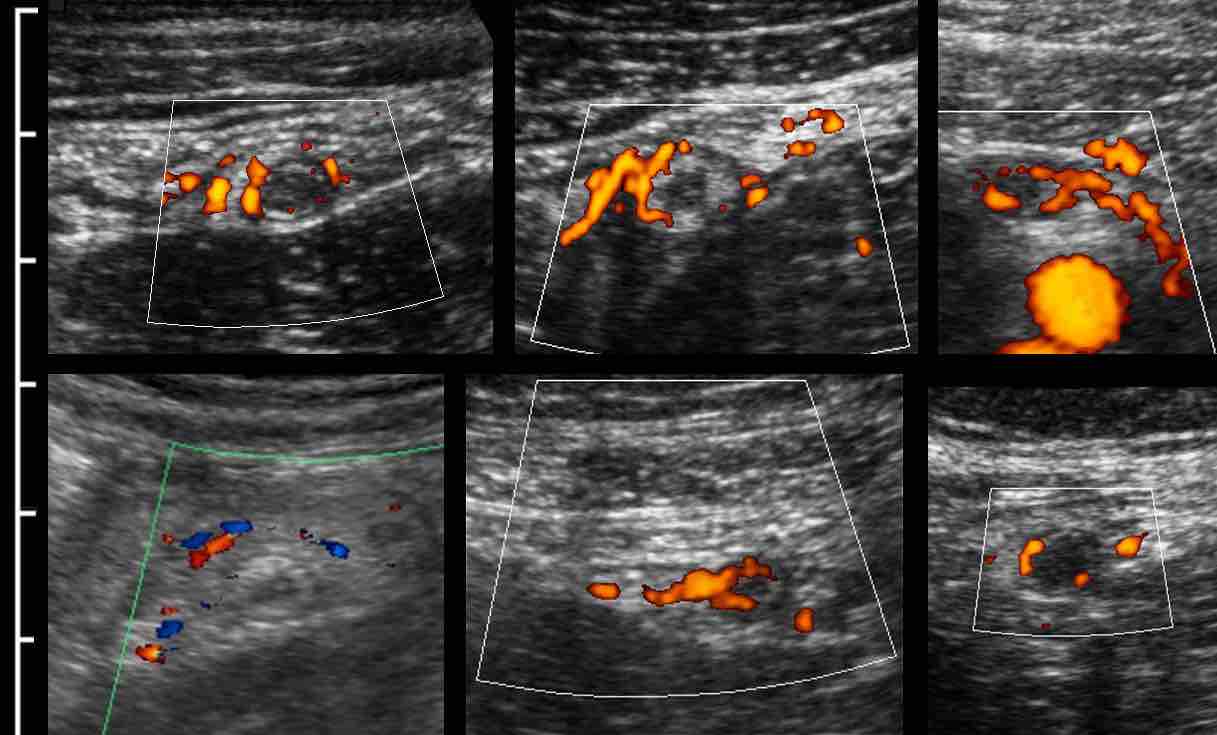

These are US images of a strongly hyperemic, edematous but small appendix in six different patients, all with rapidly decreasing symptoms at that point in time.

Note that the appendix is relatively small and has an intact layer structure.

Policy in spontaneously resolving appendicitis

Cobben et al (Radiology 2000, 215: 349-52) followed up 60 patients with spontaneous resolving appendicitis who were not operated. Within two years 23 patients had recurrent appendicitis, and in the following 15 years, another 7. This high recurrence rate (50 %) plus the fact that a future attack may come inconveniently, may play a role in clinical decision making.

It is imaginable that after each episode of appendicitis, the appendix wall becomes more vulnerable, leading to a higher chance of perforation.

In recent years, more and more patients with mild appendicitis symptoms receive antibiotics. This certainly supports a rapid recovery, but it is still uncertain if the recurrence rate will go down also (see below).

Treatment of appendicitis

Surgery

Ever since the recognition of the pathophysiological mechanism of appendicitis by Sir Reginald Fitz in 1886, there has been little doubt about the treatment: early appendectomy before perforation can occur.

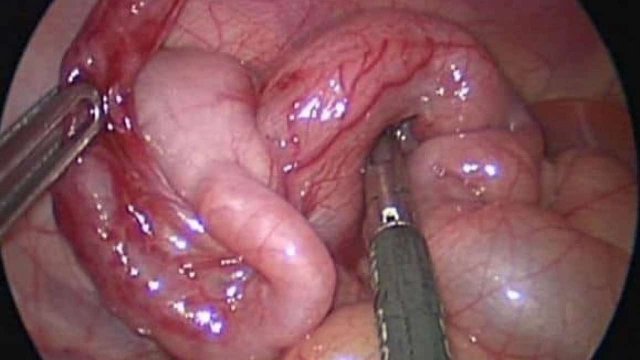

The last decades, the famous Lanz-McBurney incision is increasingly replaced by laparoscopic appendectomy.

After conservative treatment of an appendiceal mass, a so-called interval appendectomy can be done, but the usefulness of this operation remains controversial.

Until ten years ago, the use of antibiotics was limited to patients with advanced, complicated appendicitis, associated with septicaemia.

Recently, several studies have shown that early appendicitis can also be primarily treated with antibiotics only.

Antibiotics for early appendicitis

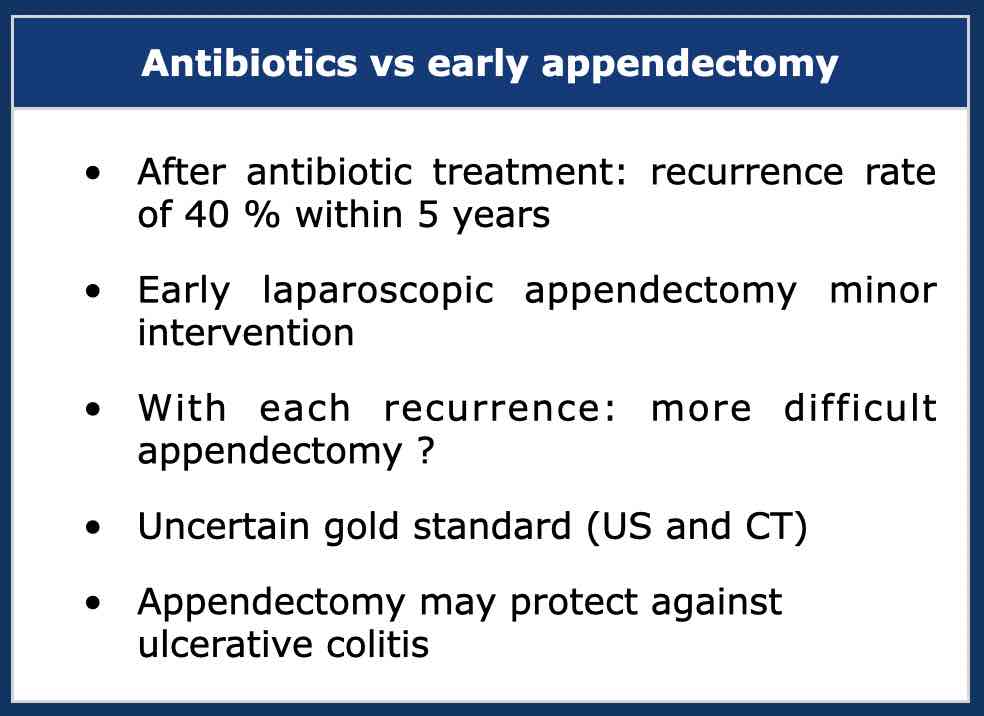

Several studies have shown that a selected group of patients with acute appendicitis and mild symptoms, first attack, low CRP, no fecolith and no perforation, can be rapidly cured with antibiotic treatment alone.

However, there is a high number of late recurrences up to 40 % for whom surgery at a later moment in time is necessary (Salminen et al. JAMA 2018;320:1259-65).

Another drawback of non-operative treatment is that US and CT are an uncertain gold standard.

The presence of a fecolith is considered a contra-indication for primary conservative treatment of appendicitis with antibiotics.

In this respect, there is a remarkable analogy with gallbladder stones.

Once a gallbladder stone (large arrow) has been proven to obstruct the gallbladder neck or cystic duct, there is wide consensus that cholecystectomy ASAP is indicated.

Similarly, patients with proven symptomatic obstruction of the appendix due to a fecolith (small arrow), should undergo appendectomy ASAP.

Gallbladder and appendix have in common:

- can be missed easily

- early removal (during or immediately after the first attack) is a fairly minimal invasive procedure

- repeated and complicated attacks may incidentally lead to considerable disease load.

Further studies will have to decide whether the 65 % of patients with obstructive appendicitis without a fecolith, will eventually benefit from primary antibiotic treatment.