Hip pathology in Children

Imaging findings

Josephine Bomer and Herma Holscher

Juliana Children's hospital, the Hague, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

In this review we will discuss the most common imaging findings in children with hip pain.

Introduction

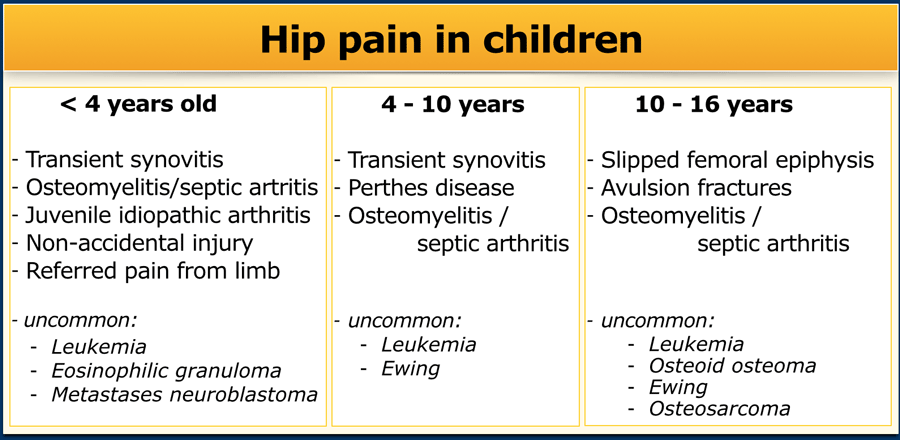

Differential diagnosis

Children with hip pathology may present with hip pain or a limp.

The differential diagnosis can be narrowed down according to age (see Table).

Young children in particular may have difficulty localizing or communicating the location of their pain; and sometimes children who initially seem to have a hip problem actually have underlying pathology of the knee or foot.

Imaging

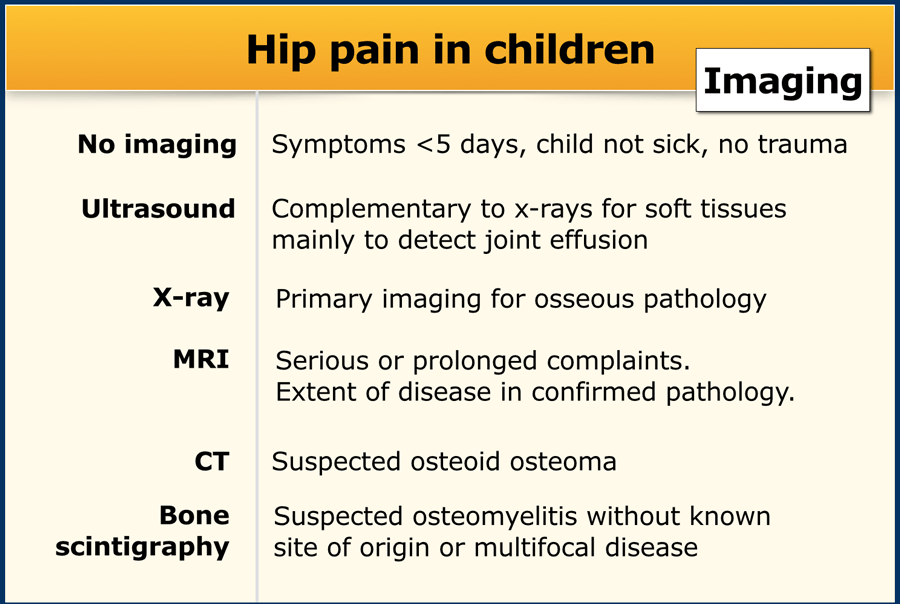

In children from 2 to 10 years old with symptoms less than 5 days, and in the absence of high fever or elevated inflammatory markers - a wait-and-see policy is recommended. In these cases the diagnosis is usually transient synovitis, which is a spontaneously resolving condition.

Sometimes the referring physician will request an ultrasound to confirm the presence of a joint effusion.

In all other cases x-ray imaging should be performed.

The diagram shows a practical approach to hip pain and a new limp.

Click on the image to enlarge.

It is important to realize that early in the course of Perthes disease, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, osteomyelitis and septic arthritis, the initial radiographs may be normal.

Because young children may have difficulty communicating the problem, it may be necessary to image the entire extremity.

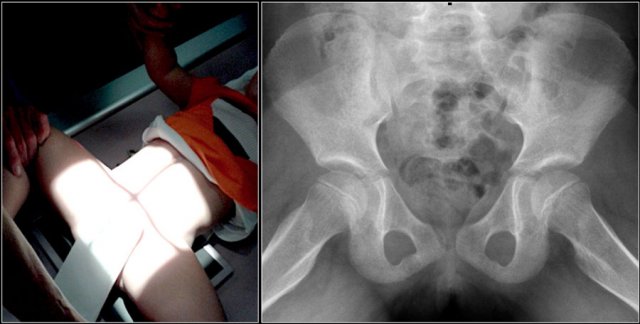

In most cases osseous pathology can be excluded with a frog-leg lateral (or Lauenstein) view only.

In case of suspected pathology on the frog-leg lateral view, an additional AP radiograph should also be acquired for orthopedic and follow-up purposes.

Children with cerebral palsy are at an increased risk for hip dislocation, and in these cases an AP-view is recommended. An AP-view is also recommended in other situations an adequate frog-leg lateral view is not possible.

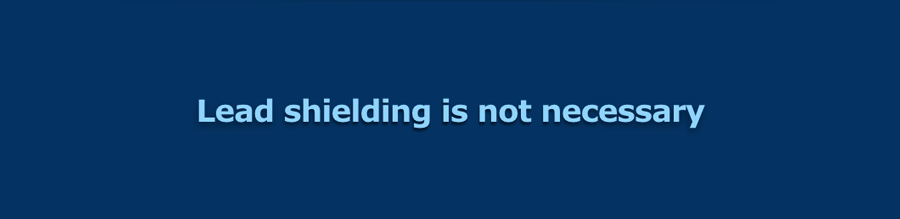

Lead Shielding

The reduction of gonadal radiation exposure with lead shielding is negligible.

Gonadal shielding is dissuaded for the following reasons:

- risk of masking important diagnostic information

- a higher number of retakes

- possible shielding of automatic exposure control chambers.

Note: as this is a relatively new insight, some of the images in this article do still include lead shielding.

Pathology

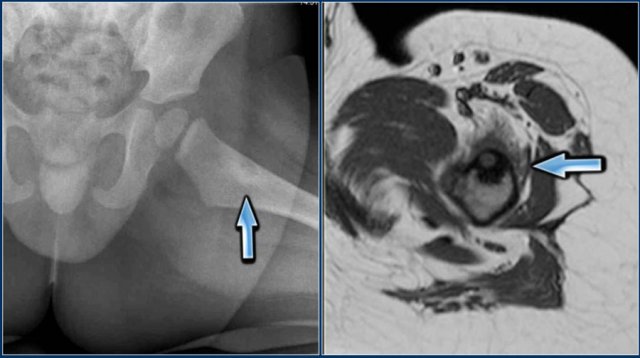

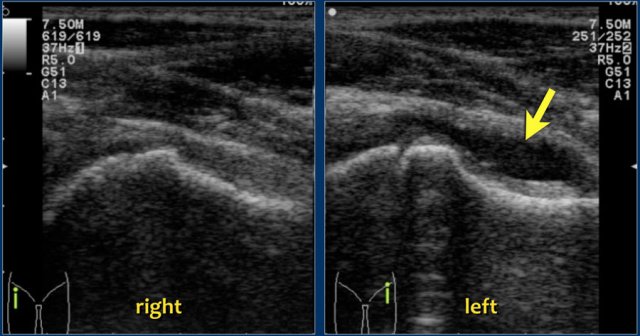

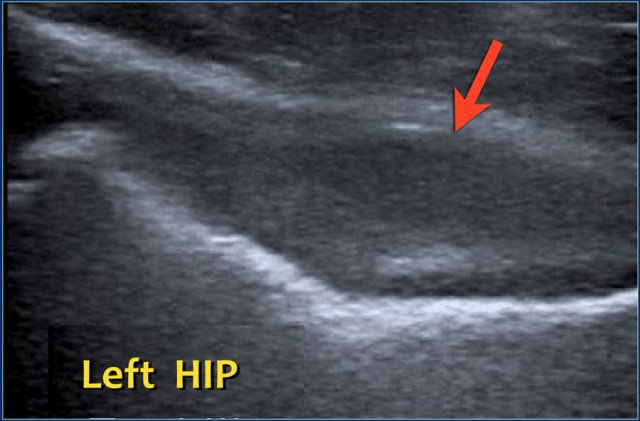

Transient synovitis. The left hip shows a joint effusion (arrow) in the anterior recess which causes separation of the layers of the capsule which are now easily recognized

Transient synovitis. The left hip shows a joint effusion (arrow) in the anterior recess which causes separation of the layers of the capsule which are now easily recognized

Transient synovitis

Transient synovitis - also known as coxitis fugax - is an aseptic inflammation of the hip, presumably of postviral etiology.

Affected children are only mildly ill or have recently sustained a low grade respiratory tract infection.

The condition is self-limiting and treated with rest and analgesics.

It is the most common cause of hip pain or a limp in children under the age of ten years.

Imaging is not strictly necessary, but an ultrasound is often requested to confirm the presence of a joint effusion.

Radiography is only performed when there are other differential diagnostic considerations.

Do not suggest the presence of an effusion on radiographs, as widening of the joint space is a non-specific finding.

Always consider the possibility of septic arthritis in a sick child!

The appearance of the effusion on ultrasound is not helpful for the differential diagnosis.

Perthes disease

Perthes disease, also known as Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, is an idiopathic avascular necrosis of the proximal femoral epiphysis.

It occurs more commonly in boys, typically between 5 and 8 years of age, but may range from the ages 3-12.

It can occur bilaterally, but it is usually asymmetric.

Early radiographs may be normal or show subtle flattening of the femoral head. Sclerosis and subchondral fractures may develop, features best appreciated on the frog-leg lateral view.

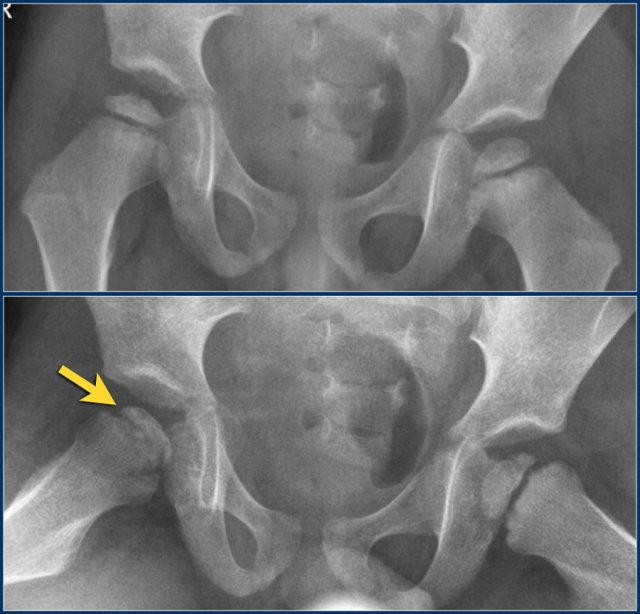

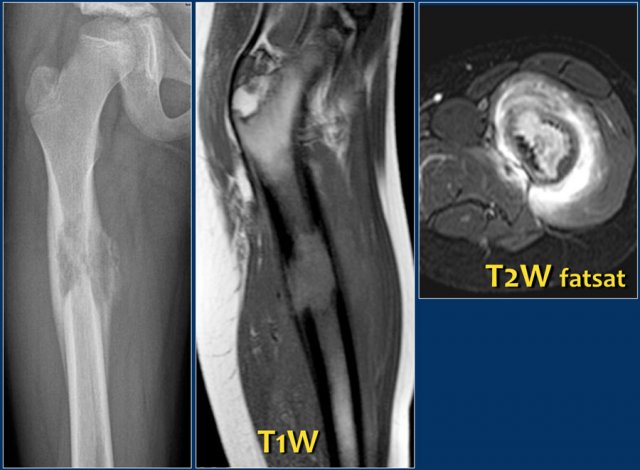

The images show Perthes disease of the right hip in a five-year old boy.

The findings are:

- Flattened and sclerotic femoral epiphysis.

- Subcondral fracture, best appreciated on the frog-leg lateral view.

Early on in the disease radiographs may be negative, but MRI will show edema in the femoral head with loss of high bone marrow signal on T1-weighted images.

Sometimes a radiographically occult fracture can be detected on MRI as a double rim sign on T2-weighted images with fatsat.

Joint effusion may be present.

Cartilage may become hypertrophic on the affected side.

The images show right-sided Perthes disease in a nine-year old girl.

There is loss of T1 high signal of the fatty marrow due to edema and sclerosis.

Treatment is symptomatic. Depending on whether or not there is spontaneous revascularization, the disease may or may not progress.

In disease progression, fragmentation and collapse of the femoral head will occur.

Metaphyseal lucencies can be seen.

In the healing phase, Perthes disease can lead to a short, broad femoral head and collum. This is also known as coxa magna deformity.

Surgical reconstruction (Salter osteotomy) may be required to prevent early osteoarthritis.

The images show:

- Collapse and sclerosis of the femoral head and metaphyseal lucency.

- Progression to fragmentation and development of a short, broad collum.

- Developing coxa magna deformity.

The radiologic differential diagnosis of Perthes disease includes:

- Secondary avascular necrosis

- Meyer's dysplasia

- Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia

Secondary avascular necrosis

Perthes disease has to be differentiated from avascular necrosis with a known cause, as this may require a different treatment approach.

Causes of avascular necrosis include:

- Steroid therapy

- Sickle cell anemia

- SLE

- A complication of hip dysplasia treatment

The x-ray is of a 15-year old with acute lymphatic leukemia who was treated with steroids.

The images alone cannot differentiate from Perthes disease, but based on the clinical information, this is secondary avascular necrosis.

Meyer's dysplasia

This is an uncommon condition in which the femoral heads show delayed ossification and fragmentation, most often occurring bilaterally.

Radiographically it cannot be differentiated from Perthes disease.

It does not show progressive collapse or deformity over time and is symmetric.

It generally occurs in a younger population (2-4 years old).

The condition itself is asymptomatic and the joints will develop normally.

Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia

Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia can mimick Perthes disease as it may manifest primarily in the hips.

It is a rare hereditary skeletal dysplasia.

Patients present with a waddling gait, pain, fatigue and short stature.

Contrary to Perthes disease, the abnormalities are usually symmetric.

The knees, ankles and wrists are usually also involved.

Endochondral ossification is abnormal and results in small, fragmented epiphyses with alignment abnormalities.

Radiographs of all joints are required to establish the diagnosis.

Patients will develop premature osteoarthritis.

The treatment is symptomatic.

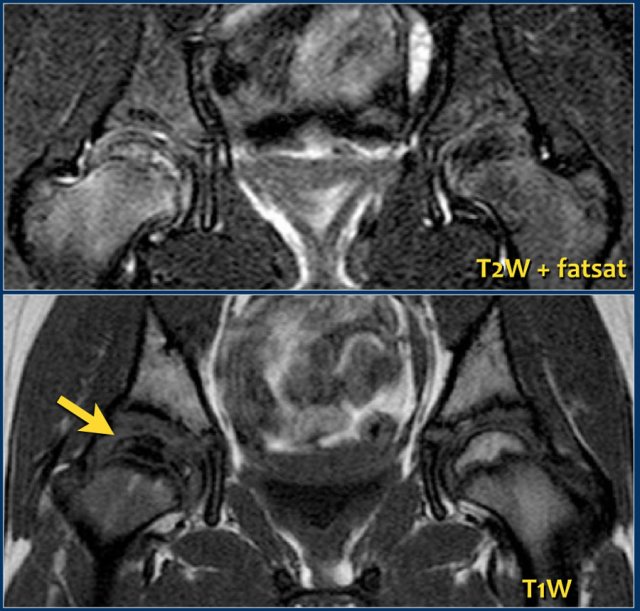

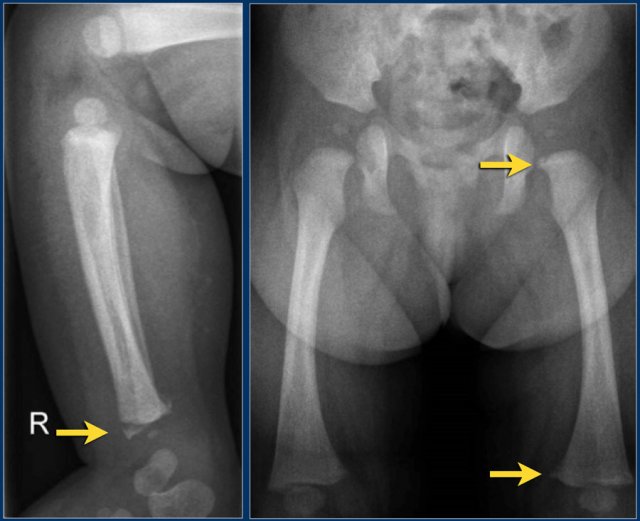

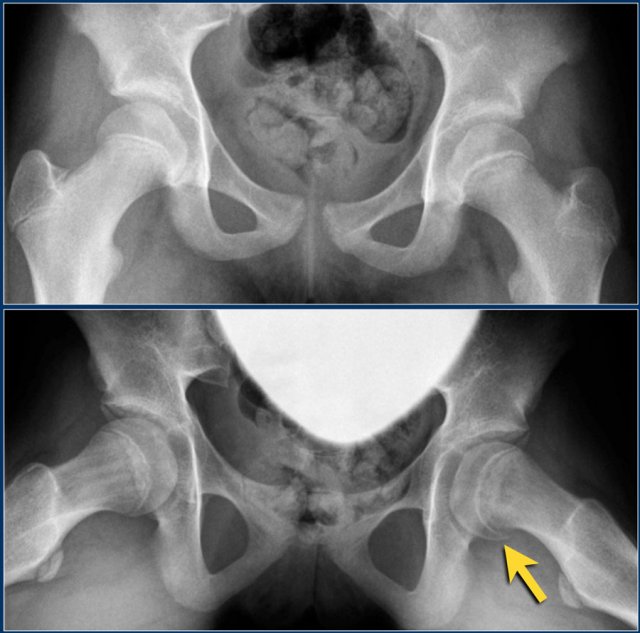

Slipped epiphysis in a thirteen-year old boy. AP radiograph shows a slightly widened epiphysis, but this can easily be overlooked. The frog-leg lateral view shows a medio-posterior slippage of the left femoral epiphysis.

Slipped epiphysis in a thirteen-year old boy. AP radiograph shows a slightly widened epiphysis, but this can easily be overlooked. The frog-leg lateral view shows a medio-posterior slippage of the left femoral epiphysis.

Slipped Capital Femoral Eiphysis

Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis (SCFE) or femoral epiphysiolysis is an idiopathic Salter-Harris type I fracture of the proximal femoral epiphysis.

It occurs more commonly in boys and in obese children. The typical age at presentation is between 12-15 years.

SCFE may occur bilaterally in up to one third of cases.

The epiphysis slips posteriorly, and to a lesser extent medially.

It is therefore best appreciated on the frog-leg lateral view.

SCFE is treated with surgical fixation to prevent further slippage.

Avascular necrosis of the femoral epiphysis is a potential complication.

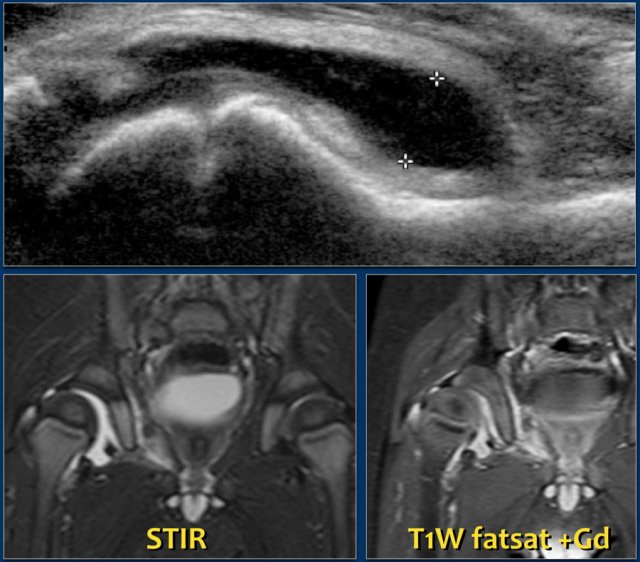

JIA: Effusion of the right hip in JIA. The synovium is thickened and loads Gadolineum contrast (right). Images courtesy of Dr LS Ording Muller

JIA: Effusion of the right hip in JIA. The synovium is thickened and loads Gadolineum contrast (right). Images courtesy of Dr LS Ording Muller

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) is a clinical diagnosis and is currently divided into six different subtypes.

In most cases, less than 4 joints are involved. Large joints are mainly affected, including the hips.

JIA begins with a tenosynovitis and only later shows bone edema, periostitis, osteoporosis and growth disturbances.

Contrary to the adult population, cartilage loss and erosions are not a frequent finding in JIA.

X-rays are usually negative early on in the disease.

Typical findings in later stages of the disease may be a slightly larger epiphysis, or accelerated bone maturation.

Since JIA is treated aggressively early on, radiographic bony changes may remain absent.

Ultrasound will show effusion, thickened synovium and sometimes hyperemia.

MRI will also demonstrate the joint effusion and synovial thickening, but can also show damage to the bone and cartilage.

It is also a great modality for the assessment of resulting growth disturbances.

Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis is a relatively common severe condition in children, occurring most frequently in children under the age of five years.

At this young age, the presentation can be rather non-specific, and infants may present only with a fever and failure to thrive.

Most cases are hematogenous, and may be a sequela of a respiratory tract infection. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen.

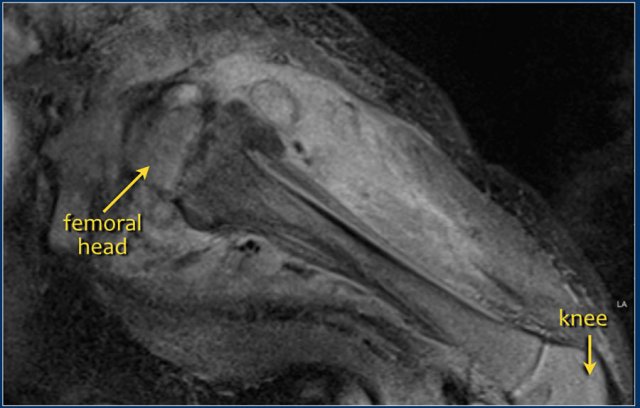

5 week old, sick infant with severe osteomyelitis of the left hip. MRI with Gadolinium contrast shows extensive soft tissue involvement and periosteal reaction.

5 week old, sick infant with severe osteomyelitis of the left hip. MRI with Gadolinium contrast shows extensive soft tissue involvement and periosteal reaction.

Most radiographs will not show abnormalities in the early stages of the disease, but after 7-10 days there may be lytic changes and periosteal reactions.

Ultrasound can be helpful in the diagnosis in cases with subperiosteal abscess formation.

In suspected osteomyelitis, MRI is the imaging method of choice. In infants or young children in whom the location may be uncertain, bone scintigraphy can be useful.

Both MRI and bone scintigraphy show abnormalities in the early stages of the disease.

On MRI osteomyelitis appears as an area of T2 increased signal in the metaphysis with enhancement and surrounding edema in the soft tissues, and occasionally a subperiosteal abscess.

In infants and children with closed growth plates, the growth plate does not act as a barrier and infection may spread to the epiphysis and joint.

.

At four months follow-up a residual, but less prominent periosteal reaction is present and there is accelerated bone maturation.

In osteomyelitis bone scintigraphy will show an area of increased uptake.

Osteomyelitis is treated with i.v. antibiotics and has a good prognosis if detected promptly.

Brodie's abscess

A subtype of osteomyelitis which is typically seen in children is a Brodie's abscess.

It is a subacute osteomyelitis with intraosseous abscess formation.

The only complaint can be pain.

Fever and inflammatory markers may be absent.

The abscess is usually located in the metaphysis of long bones, but may be located in the epiphysis in young children.

On x-ray there is a sharp defined oval lytic lesion with or without a sclerotic rim, with its long axis parallel to the long axis of the bone (see figure).

On MRI the lesion is hyperintense on T2WI. There is joint effusion and only minimal edema in the surrounding musculature.

Five-year old boy with a limp and fever at presentation. Ultrasound was difficult because the boy was unable to stretch his leg, but the left hip clearly shows an effusion and synovial thickening. Pus was evacuated in the operating theater.

Five-year old boy with a limp and fever at presentation. Ultrasound was difficult because the boy was unable to stretch his leg, but the left hip clearly shows an effusion and synovial thickening. Pus was evacuated in the operating theater.

Septic arthritis

Septic arthritis is a surgical emergency.

The inflammation of a joint in septic arthritis is bacterial and, as in osteomyelitis, is usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus.

Septic arthritis can have a rapidly deteriorating course with destruction of the joint.

Affected children are ill, with fever and severe joint pain.

On ultrasound there is joint effusion (as previously mentioned, the echogenicity is not of diagnostic value).

The synovium may be thickened, but this is a non-specific finding also found in other inflammatory pathology such as JIA.

The clinical profile, laboratory findings and the presence of a joint effusion are suggestive of septic arthritis. Subsequent aspiration of pus confirms the diagnosis.

Surgical debridement should take place as soon as possible.

Radiographs are not sensitive to joint effusion and are not helpful in the early diagnosis.

Nevertheless, they should be acquired for follow-up purposes.

Joint space narrowing and osteolysis will become visible in later stages of the disease.

MRI may be helpful to assess the extent of disease and can detect possible concomitant osteomyelitis.

NOTE:

Absence of joint effusion excludes septic arthritis.

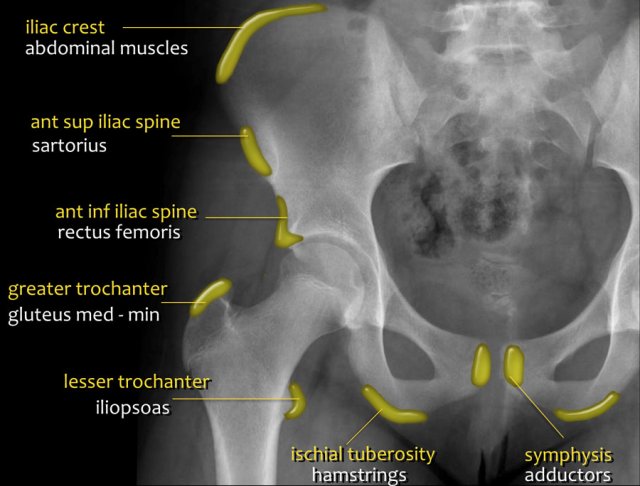

Avulsion injuries

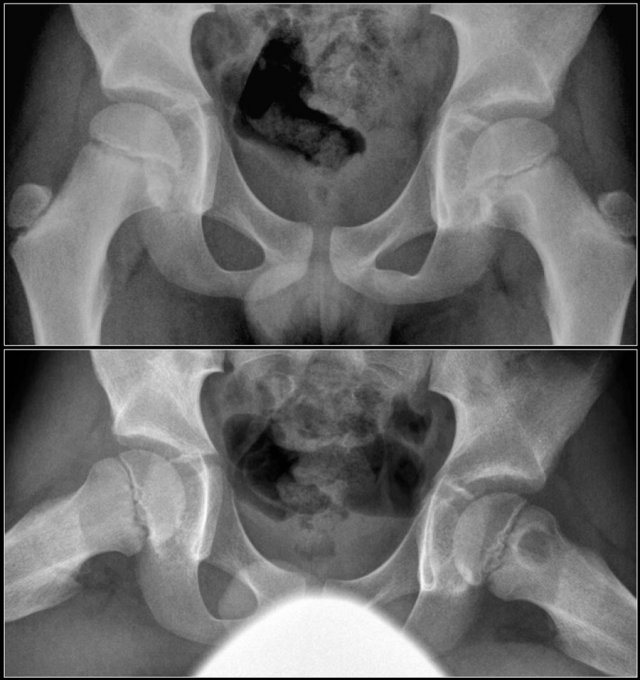

Avulsion injuries of the pelvis are a frequent cause of hip pain in adolescents involved in sports.

Because at this age the tendons are generally stronger than the apophyses, strong muscle contraction can result in apophyseal avulsion fractures.

Avulsion injuries can be acute or chronic.

Typical avulsion injury of the anterior inferior iliac spine at the insertion of the rectus femoris tendon.

Typical avulsion injury of the right ischial aphophysis.

Bone tumors and tumor-like lesions

There are many bone tumors and tumor-like lesions that may cause pain in the hip or upper leg.

We will not discuss the various bone tumors here, but osteoid osteoma must be addressed, since it is a relatively common tumor, and the cortex of the femoral neck a common location.

Osteoid osteoma is a benign tumor characterized by an extensive bony reaction and severe bone pain, occurring mainly at night.

X-ray imaging shows a small oval lytic lesion which may be obscured by the dense, bony reaction surrounding it.

MRI shows the nidus.

Other bone tumors and tumor-like lesions such as eosinophilic granuloma may also be the underlying cause of a painful hip.

Knee and foot

As mentioned previously, young children may have difficulty communicating the cause of their pain or limp.

In such cases it is wise to analyze their gait and image the entire extremity.

A toddler's fracture (image) may be one of the possible underlying causes.

Corner- or bucket handle fractures should raise the suspicion of non-accidental injury (NAI)

See section on child abuse.

In 524 children analyzed for hip pain we found three cases of mesenteric adenitis.

In some atypical situations an abdominal ultrasound may therefore be of value.