Cardiovascular Pearls on Chest CT.

Onno Mets¹ and Robin Smithuis²

¹Radiology department of the University Medical Center Amsterdam and ²Alrijne hospital in Leiden, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

The primary focus of chest-CT is often on the pulmonary

parenchyma and associated pathology.

However, beyond the pulmonary domain, chest CT also provides

valuable insights into the cardiovascular system, although it is frequently

beyond the scope of imaging indication.

Due to the wealth of information on non-cardiac chest CT

scans, there is a risk of oversight for those not specifically trained in or

focused on cardiovascular

radiology.

In this article we provide a systematic diagnostic approach to the heart and vessels, and we will discuss the following helpful tools:

- 'Five corner approach' - a simple diagnostic method to detect vascular variants.

- 'Go with the flow' - a more systematic approach to study the cardiovascular structures as blood flows towards the right atrium and eventually leaves the left ventricle.

Introduction

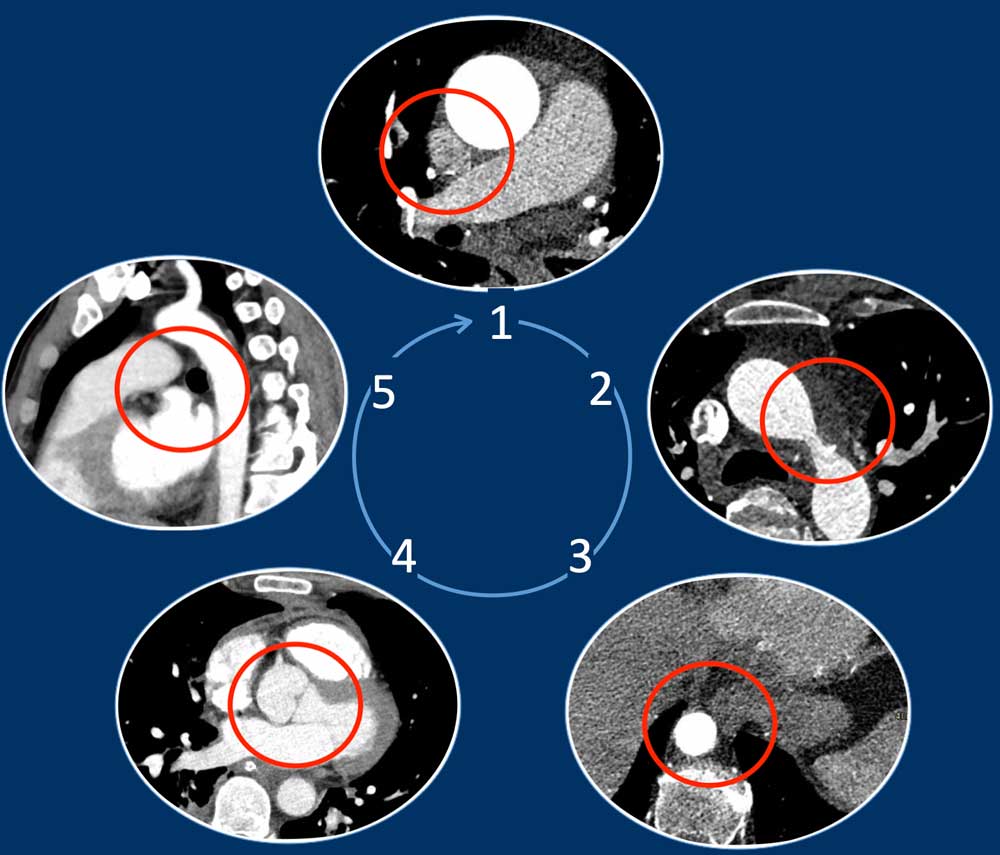

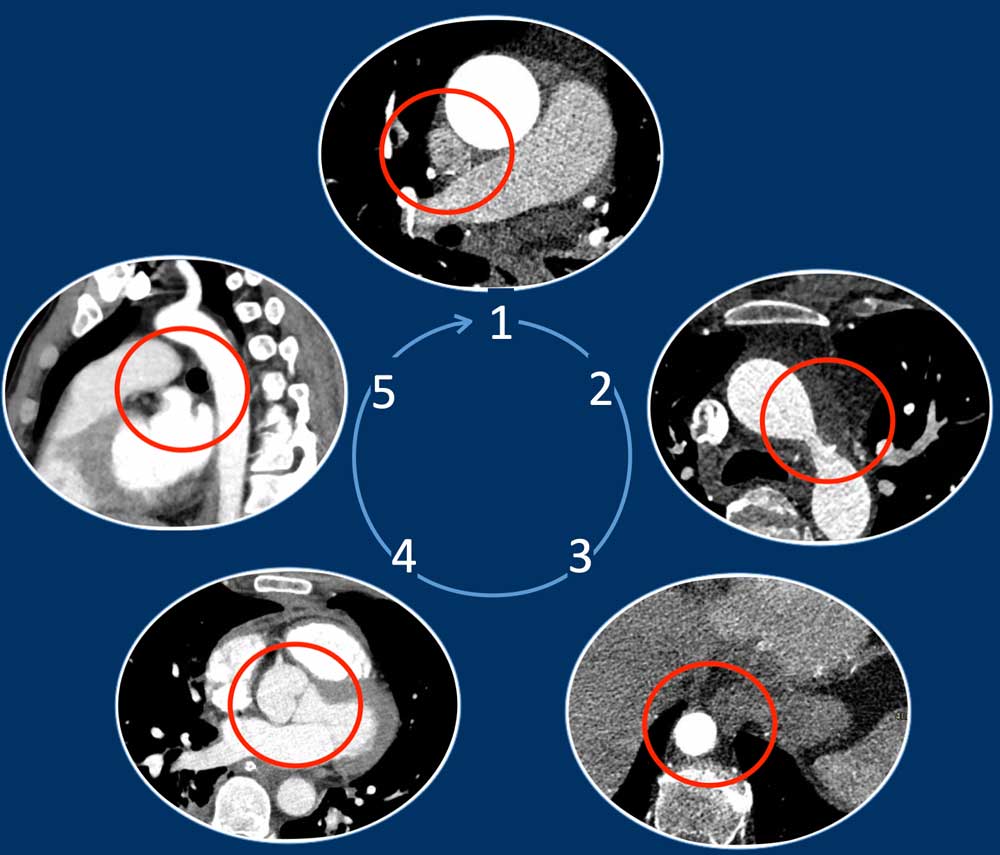

Five Corner approach

Detecting vascular anomalies on non-cardiac chest CT scans can be

challenging, especially when they are not suspected and therefore not the primary focus of the examination.

By just checking five corners it is possible to detect the vast majority of vascular variants:

- Intersection of the right superior pulmonary vein and superior caval vein (axial view)

DD: Right partial anomalous pulmonary venous return (PAPVR). - Lateral to the aortic arch (axial view)

DD: left-sided caval vein, levo-atrial cardinal vein, left PAPVR, left superior intercostal vein. - Descending aorta at the level of the diaphragm (axial view)

DD: systemic arterial supply of the lung, azygos continuation of the inferior caval vein, Scimitar vein. - Level of the aortic root (axial view)

DD: abnormal origin of the coronaries. - Aortic-pulmonary window (sagittal view)

DD: patent ductus arteriosus, aortic diverticulum, aberrant right subclavian artery.

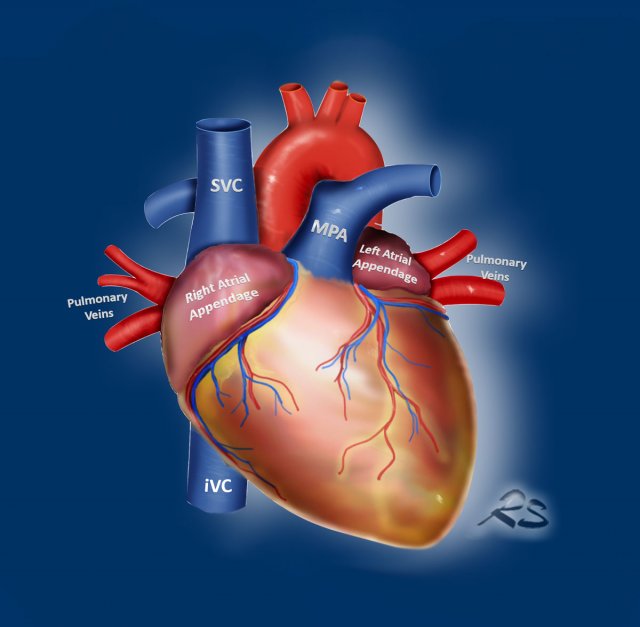

Go with the flow

An easy way to study the cardiovascular structures is to use the ‘go-with-the-flow’ method.

This evaluates

the structures transferring the blood as it enters through

the caval veins, through the right side of the

heart into the pulmonary arteries, that carry the blood to the lungs.

Then the blood travels back

through the pulmonary veins into the left atrium and ventricle to enter the aorta and major branches including the coronary arteries.

Look for the following abnormalities:

- IVC and SVC

Azygos continuation of the IVC, Left-sided SVC, Levo-atrial cardinal vein. - Right side of the heart

Dilation, Thrombus, Myxoma, Tricuspid vegetation, Hypertrophy. - Pulmonary Arteries

Dilation, Central thrombo-embolic disease. - Pulmonary Veins

Anomalous pulmonary venous return. - Left Atrium and Appendage

Dilatation, Thrombus, Myxoma, Cor triatriatum, Septal defect. - Left Ventricle

Dilation, Hypertrophy, Perfusion abnormalities, Post-myocardial infarction, Aneurysm and Thrombus. - Aorta and branches

Calcifications, Aneurysm, Branch stenosis and occlusion, Patent ductus arteriosus, Aberrant right subclavian artery, Abnormal origin of the coronaries.

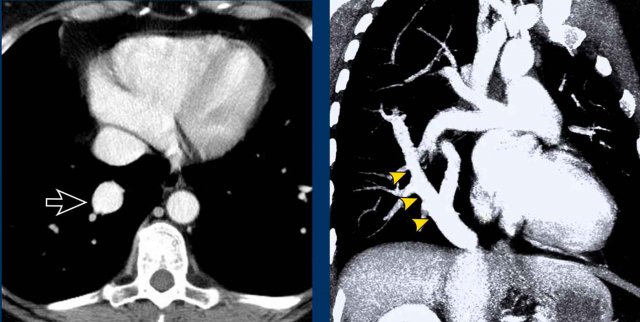

SVC and IVC

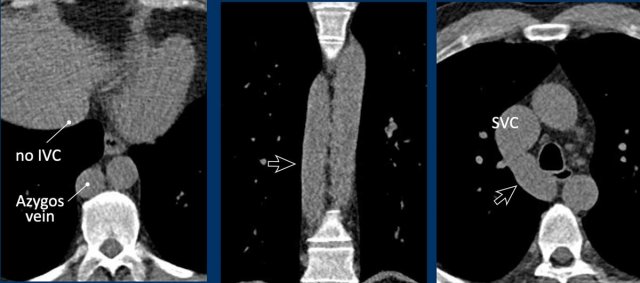

Azygos continuation of the inferior vena cava

In this variant there is absence of the infrahepatic portion of the IVC with the infrarenal and renal segments draining via an enlarged azygos vein into the superior caval vein.

The supra-hepatic segment of the IVC is present but drains only blood from the hepatic veins into the right atrium.

Azygos continuation of the inferior caval vein is normally an incidental finding in asymptomatic patients, although it might be associated with other cardiovascular abnormalities, as well as with splenic absence or polysplenia.

The importance of not overlooking this condition lies mainly in its relevance for surgical planning as well as endovascular procedures, as it prevents catheterizing the right heart from inferior.

Images

Azygos continuation of the IVC showing the characteristic ‘double aorta’ configuration at the level of the diaphragmatic crus, and dilatation of the azygos vein all the way towards the connection to the SVC.

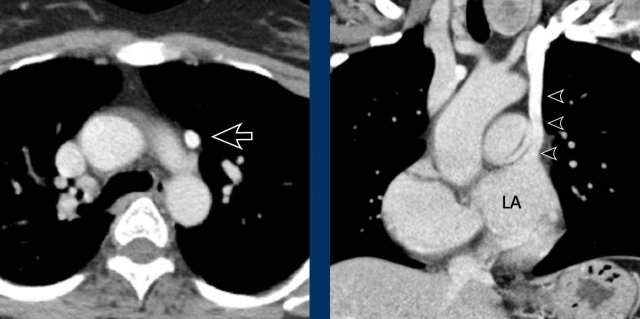

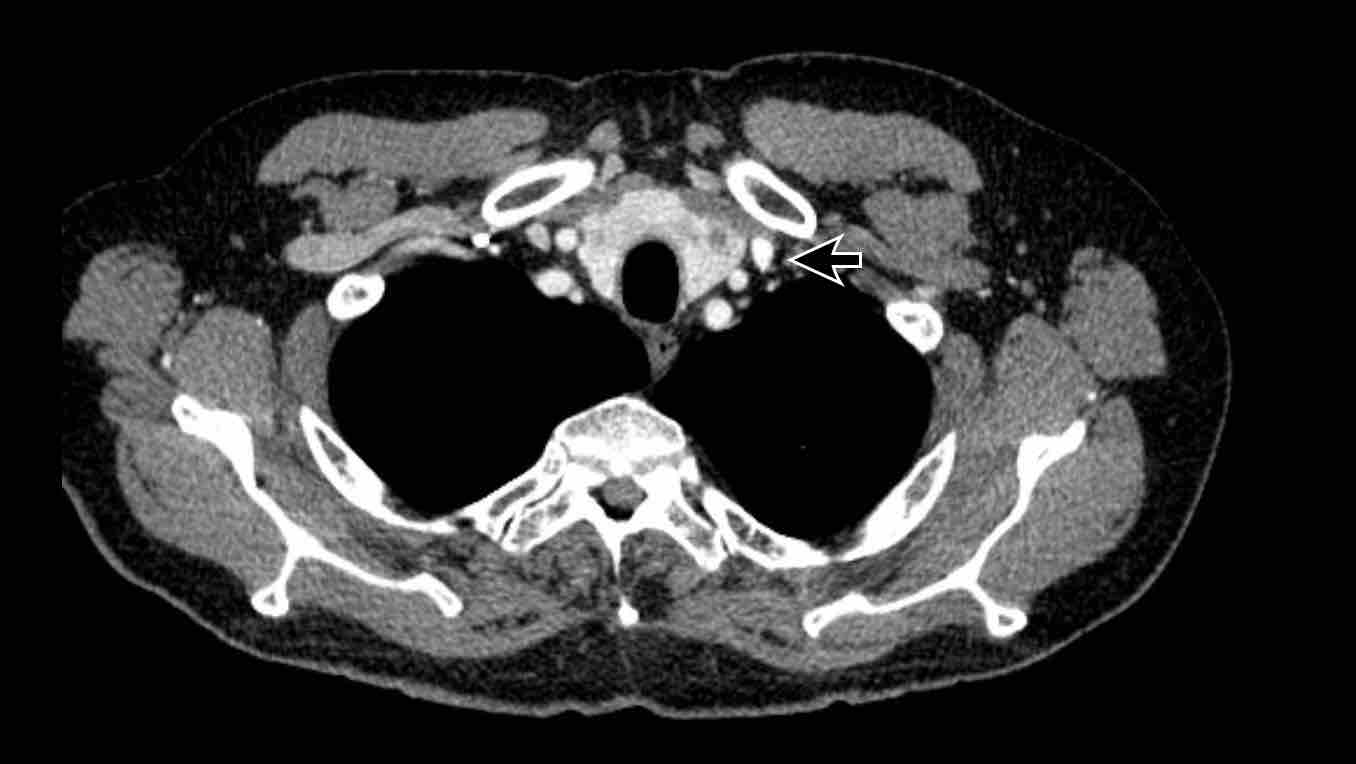

Persistent left superior vena cava

This is the most common thoracic venous anomaly and may be seen either

in isolation or as component of more

complex congenital pathology.

The vein begins at the confluens of the left

subclavian and internal jugular vein, passes through the left side of the

mediastinum adjacent to the arcus aorta, and typically drains into the

right atrium via the coronary sinus.

For a vessel in this location, lateral to the

aortic arch, there is a differential diagnosis of four:

- Left SVC

- Levo-atrial cardinal vein (LAVC)

- Partial anomalous venous return of the left upper lobe

- Left superior intercostal vein.

Levo-atrial cardinal vein

A rare vascular anomaly that some consider a left-sided SVC connecting to the left atrium is the levo-atrial cardinal vein (LACV). However, one may argue its behavior is more on the anomalous pulmonary venous return spectrum.

Although in levo-atrial cardinal vein, the pulmonary veins drain normally into the left atrium, there is an anomalous venous connection between the left atrium and left brachiocephalic vein, creating a left-to-right shunt.

Due to its location a levo-atrial cardinal vein may easily be misinterpreted for a left-sided superior caval vein, however, a left SVC should connect to the coronary sinus and right atrium and just represents a venous variant and not a cardiovascular shunt. Simply check the drainage site to differentiate these two.

Left superior intercostal vein - Aortic nipple

A mimicker of a

vascular variant lateral to the aortic arch is the left superior

intercostal vein.

This is a normal venous structure considered part of the hemi-azygos system, and is sometimes more prominent than in others depending on collateral flow.

Due to

its location it may suggest an anomalous pulmonary venous return, left-sided SVC or levo-atrial cardinal vein, however, assessment of the origin and course of the vascular structure will help separate this

normal venous structure from the above mentioned differential diagnoses of vascular

anomalies.

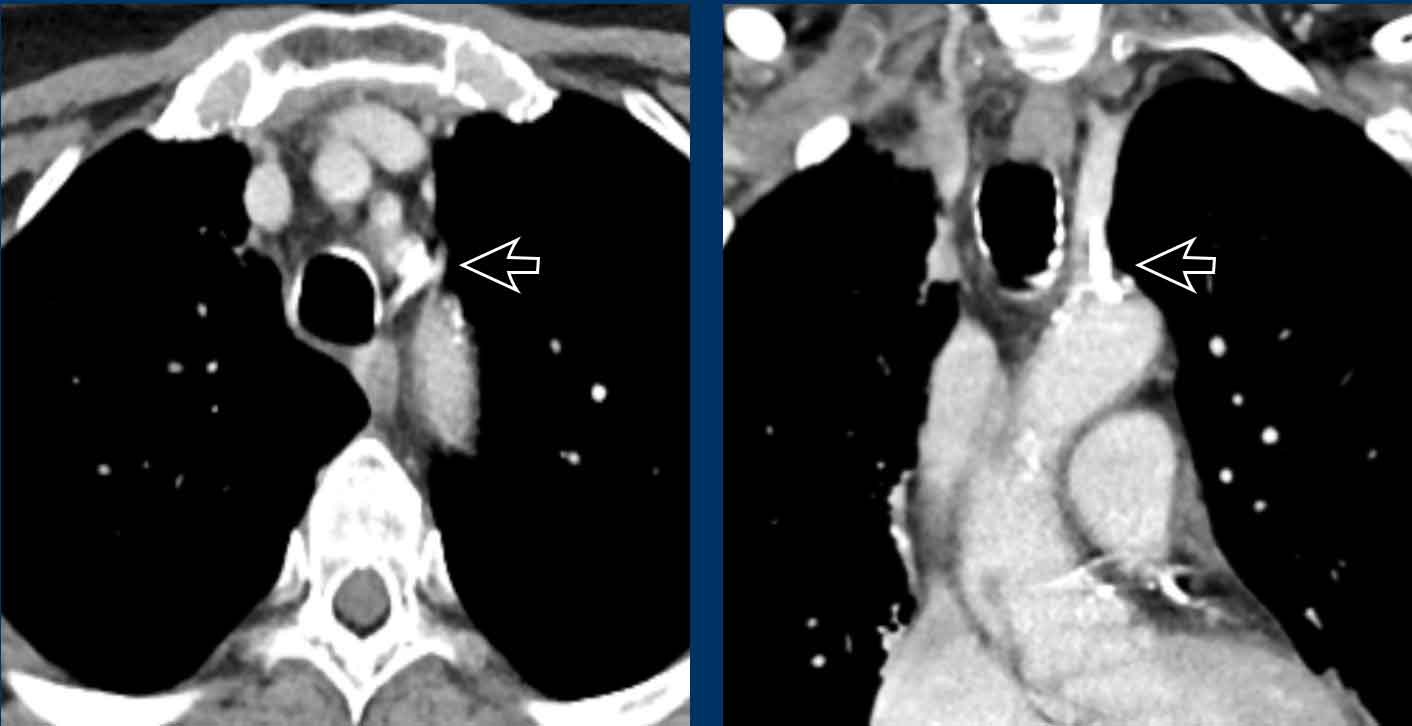

Images

Prominent

left superior intercostal vein, sometimes referred to as ‘aortic

nipple’.

Notice te resemblence to the levo-artial cardinal vein (on the axial view).

Right side of the heart

Tricuspid valve

The majority of cases of right-sided infective endocarditis involve the tricuspid valve and are associated with intravenous drug use. In addition to intravenous drug users, patients with hemodialysis catheters, pacemakers, and defibrillator leads are also at increased risk for tricuspid valve infective endocarditis.

Image

Massive infectious vegetations on the tricuspid valve in an intravenous heroin user with S. Aureus endocarditis.

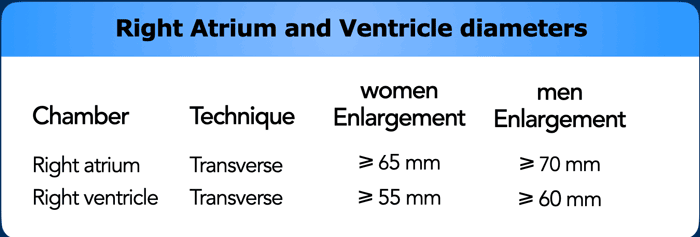

Right heart dilatation

The right atrium generally dilates due to

tricuspid valvular disease, which may be primary or secondary to right

ventricular pathology. The right ventricle can be dilated due to various

reasons, either in acute setting or more chronically.

In the acute setting

massive thrombo-embolic disease may lead to outflow obstruction and ballooning

of the right ventricle, which is inversely related to morbidity and mortality.

More chronically, RV dilation can be seen in right-sided cardiomyopathy, congential abnormalities, and pulmonary hypertension due to various etiologies, including chronic thrombo-embolic disease.

Adaptation and remodelling of the right ventricle shows a spectrum of dilation, hypertrophy and eventually failure.

Right heart failure will lead to ascites and body edema, in contrast to left heart failure which leads to congestion with pulmonary edema and pleural effusions.

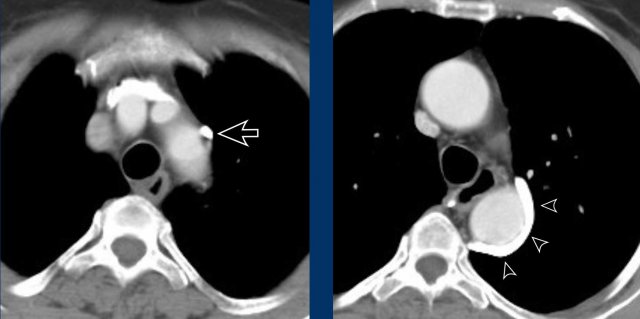

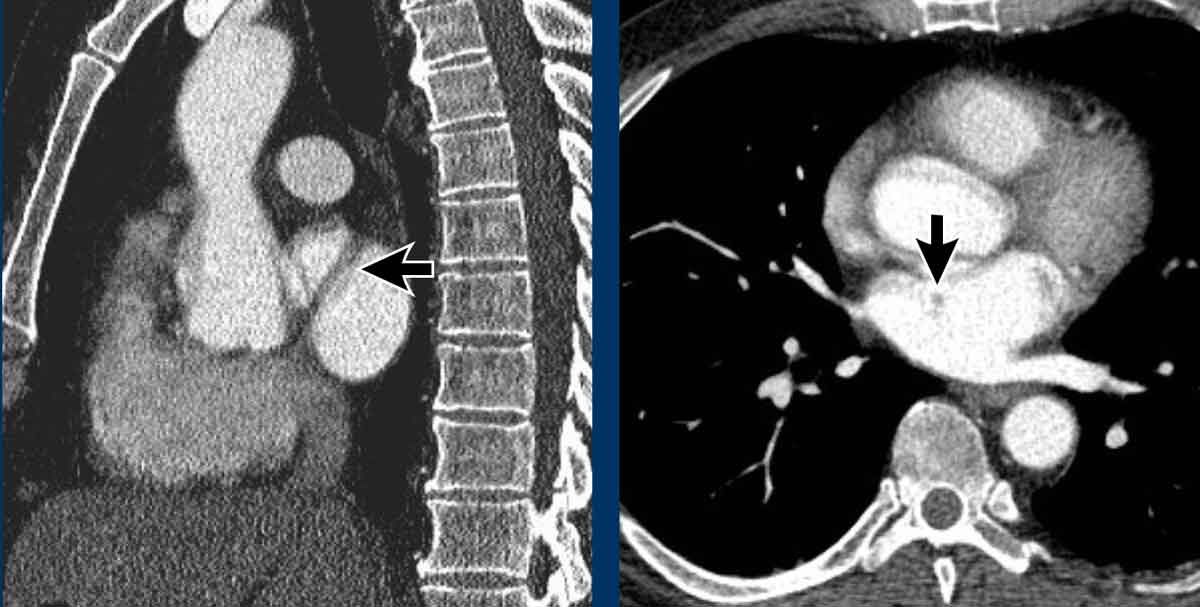

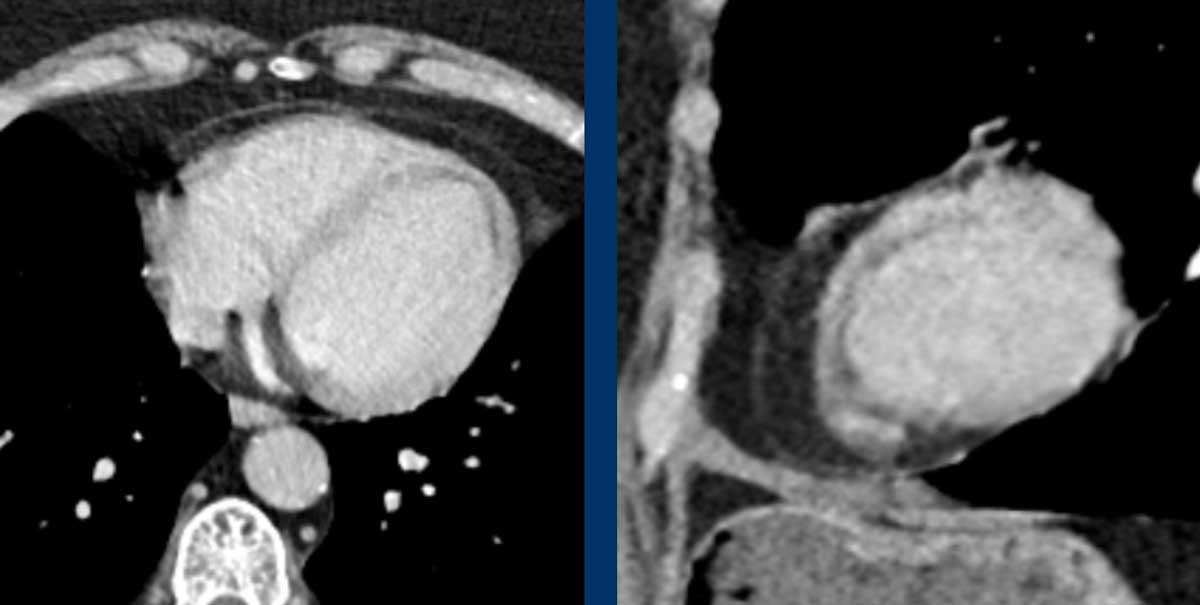

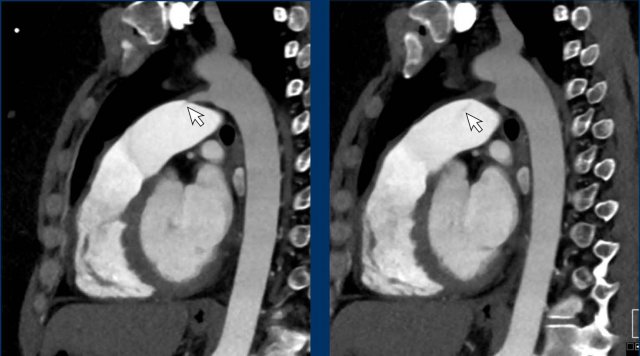

Image

Central wall-adhering thrombus in a patient with chronic thrombo-embolic disease with right heart dilation, consistent with chronic thrombo-embolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH).

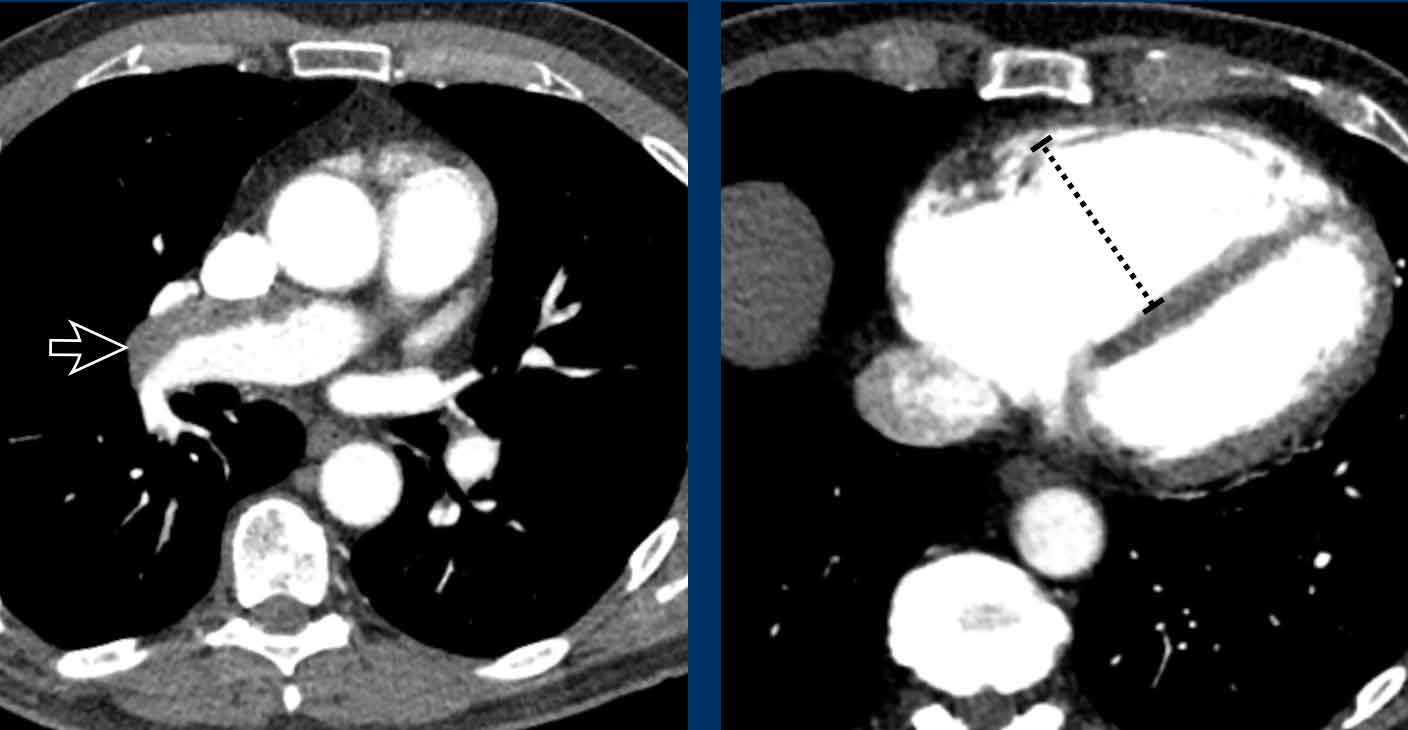

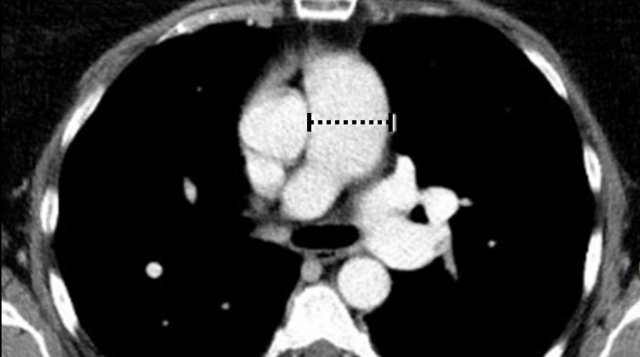

Pulmonary Arteries

Dilatation of the main pulmonary artery (MPA) may reflect

primary or secondary pulmonary hypertension.

As in aortic dimensions, size may differ between patients

based on multiple factors, such as sex, age, BSA, etc.

In the general population with a low risk of pulmonary hypertension, main pulmonary artery diameter > 34 mm, or a

MPA-to-Aorta ratio >1.1, should be reported as dilated.

In high risk populations with predisposing factors such as

left heart disease, COPD, systemic sclerosis etc. the threshold lowers to >

30 mm, or an MPA-to-Aorta ratio > 0.9.

When a dilation of the pulmonary artery is seen this should trigger the search for markers of possible etiology, within the study limitations of non-cardiac chest CT.

This can help in recommending additional imaging modalities, as well as referral to the correct clinician.

Dilation may for example be caused by underlying chronic pulmonary emboli, congestion due to left heart disease, fibrotic and other severe lung disease, or due to a left-to-right-shunt in a vascular anomaly.

Image

Dilated pulmonary artery of 38 mm due to a cardiovascular left-to-right shunt (ie. PAPVR).

Pulmonary Veins

Anomalous pulmonary venous return

This figure is shown before.

By checking these five corners it is possible to detect the vast majority of vascular variants, and is especially helpful to detect pulmonary venous anomalies (in bold):

- Intersection of the right superior pulmonary vein and superior caval vein (axial view)

DD: Right partial anomalous pulmonary venous return (PAPVR). - Lateral to the aortic arch (axial view)

DD: left-sided caval vein, levo-atrial cardinal vein, left PAPVR, left superior intercostal vein. - Descending aorta at the level of the diaphragm (axial view)

DD: systemic arterial supply of the lung, azygos continuation of the inferior caval vein, Scimitar vein. - Aortic-pulmonary window (sagittal view)

DD: patent ductus arteriosus, aortic diverticulum, aberrant right subclavian artery. - Level of the aortic root (axial view)

DD: abnormal origin of the coronaries.

Anomalous pulmonary venous return (2)

Normally the oxygenated blood runs from all lung lobes to the

left atrium through several pulmonary veins.

Although number and size of pulmonary veins may vary between patients, site of drainage should not.

In abnormal pulmonary venous return there is drainage into

the systemic circulation rather than into the left atrium, creating a

left-to-right shunt. Drainage can either be supracardiac (eg. caval

vein), cardiac (eg. right atrium), infracardiac (eg. IVC) or mixed (ie.

combination of the above).

In adults there is most often a partial anomalous return (PAPVR) as

compared to total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR), which is a severe

congenital abnormality that is not incidentally found on chest CT later in life.

The impact

the anomaly has on the right

side of the heart, as well as presence of symptoms such as dyspnea, depend on the shunt

fraction. If small, a PAPVR may prove to be a clinically

irrelevant finding.

In PAPVR most often the left upper lobe drains into the left

brachiocephalic vein.The next most common anomaly is the right upper lobe draining into the

superior caval vein.

A right-sided PAPVR has a strong association with a sinus venosus defect

(approx. 40%), wich is an atrial septal defect at the location of the

cavo-atrial junction. One should thus check for the presence of this type of

ASD when a right PAPVR is seen.

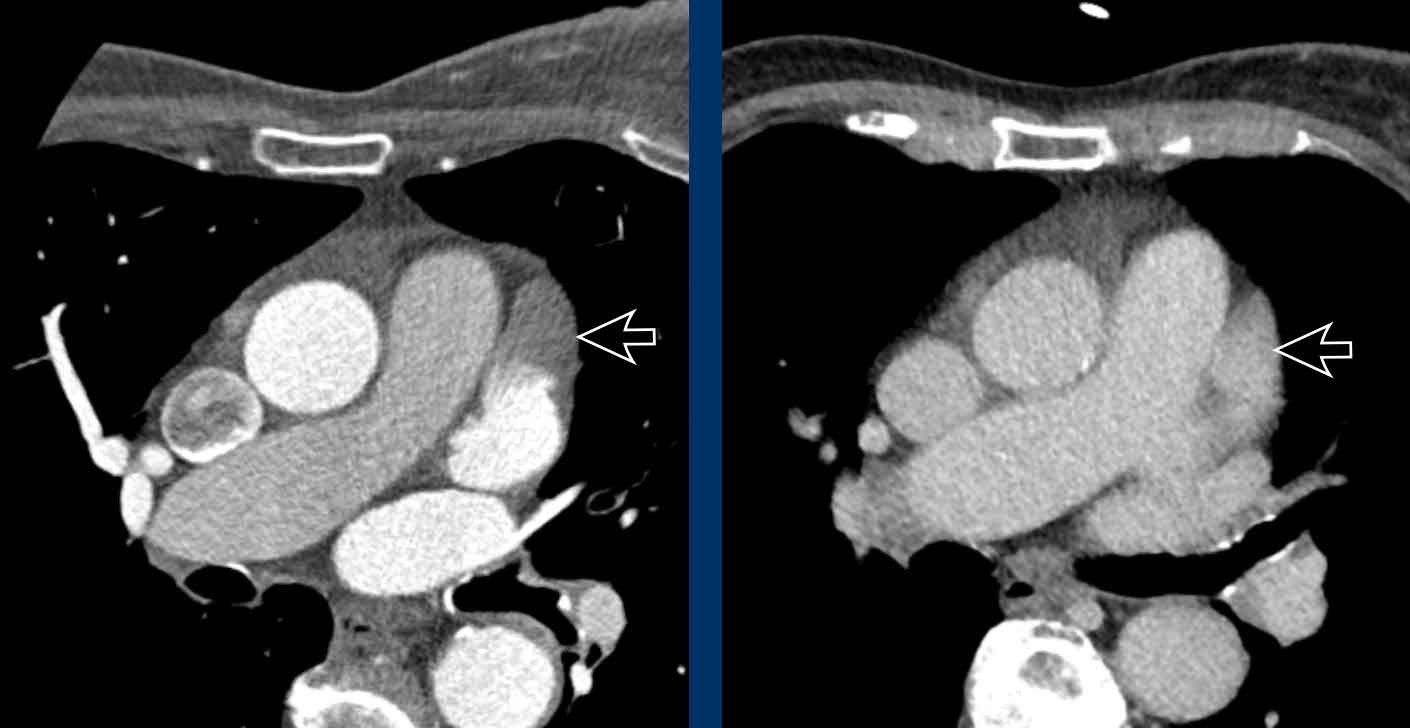

Images

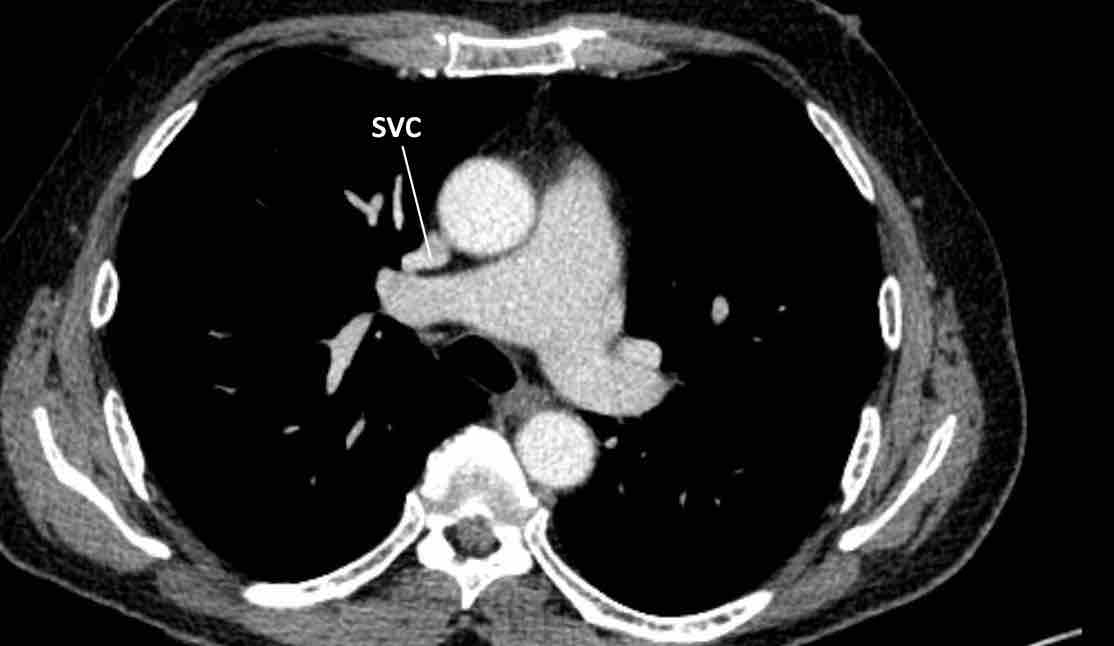

This patient was scheduled

for right upper lobe lobectomy for lung cancer and the vascular anomaly was

initially missed on CT imaging.

The peroperative

implications of such an anomaly underline the importance of not overlooking

such variants.

Scroll through the images.

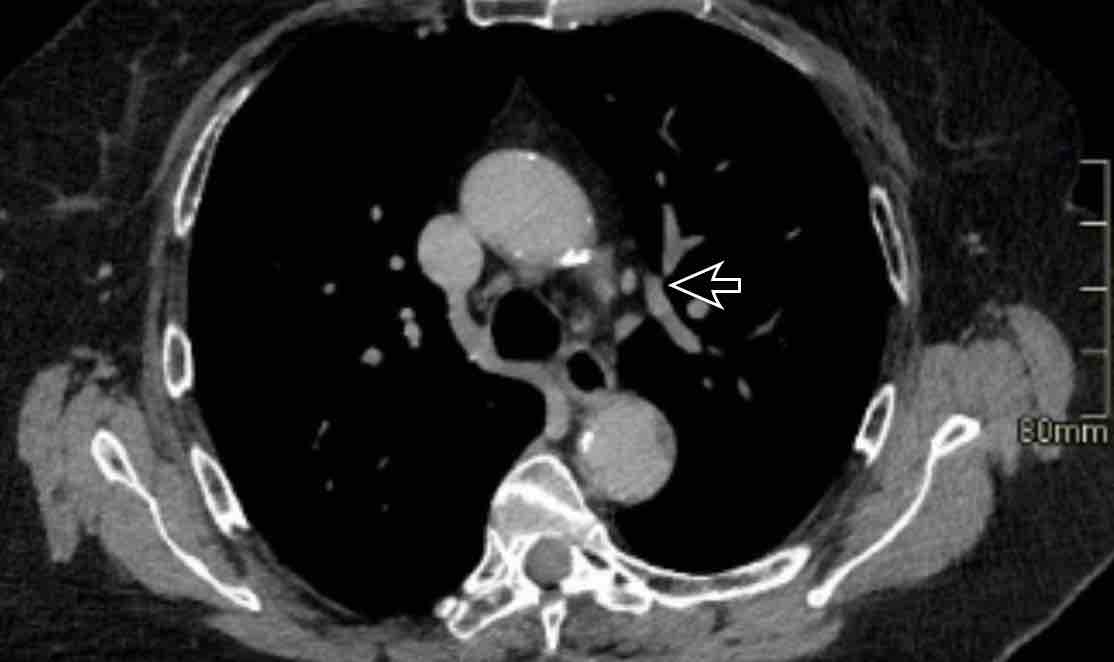

Images

Incidental left-sided PAPVR with supracardiac drainage of blood from the left upper lobe into the left brachiocephalic vein (arrows).

Scimitar vein

A scimitar vein is a PAPVR of the right lung draining infracardially, most often into the IVC.

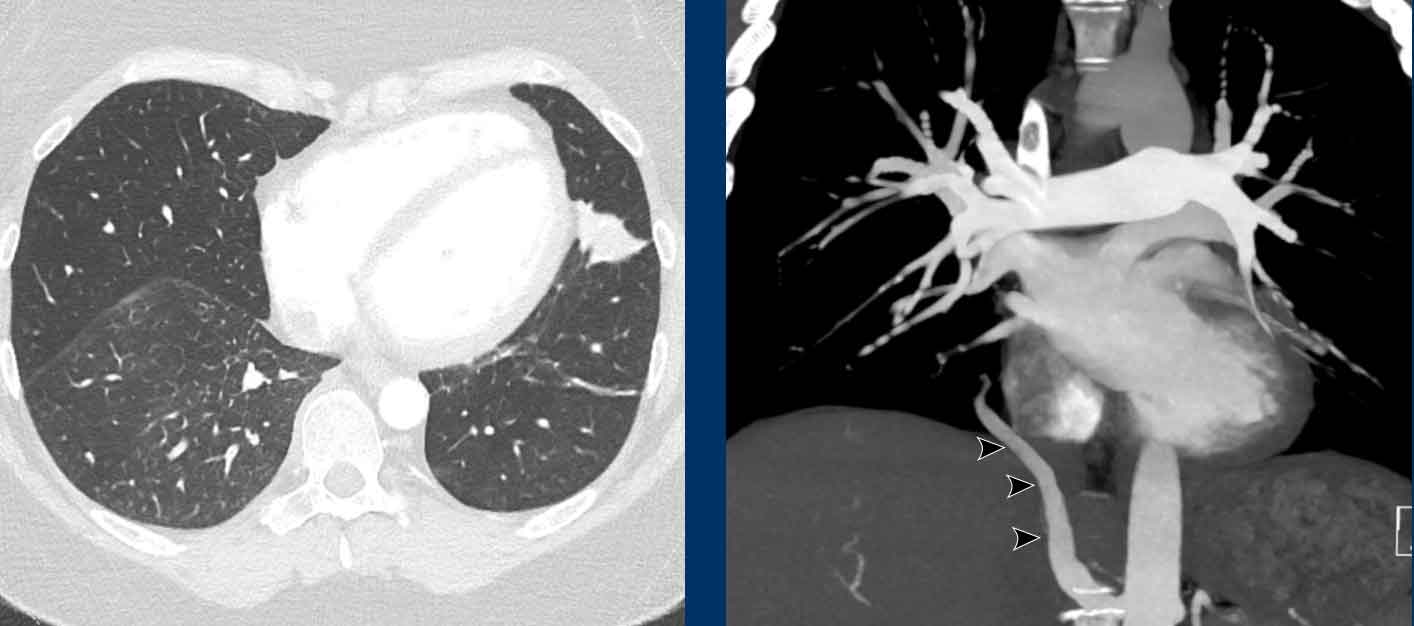

Images

PAPVR of the right lower lobe, draining blood into the IVC. This is also known as a Scimitar vein, due to its resemblance to a certain type of sword.

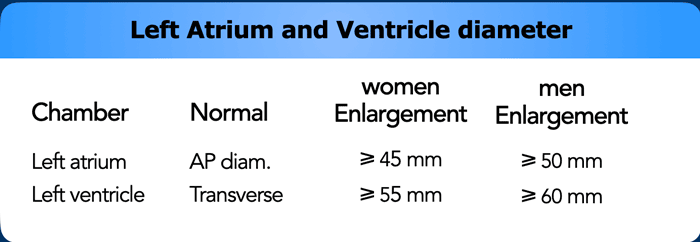

Left Atrium and Appendage

Dilatation of Left Atrium

Left

atrial dilation is a very common finding and most often related to atrial fibrillation

and mitral valvular heart disease.

Dilation of the left atrium may coincide

with arrhythmias and cloth formation, increasing the risk for embolic events.

Thrombus

The most common intracardiac mass is a thrombus, which is often

located in the left atrial appendage (LAA), predominantly in patients with atrial

fibrillation and significant dilation.

Nevertheless, thrombus may also be seen in the right atrium in relation to a

central venous catheter or in a left ventricle apical aneurysm after prior

myocardial infarction.

Scroll through the images of a patient with atrial fibrillation.

What are the findings?

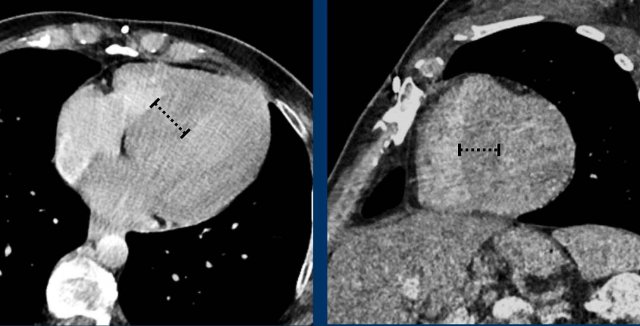

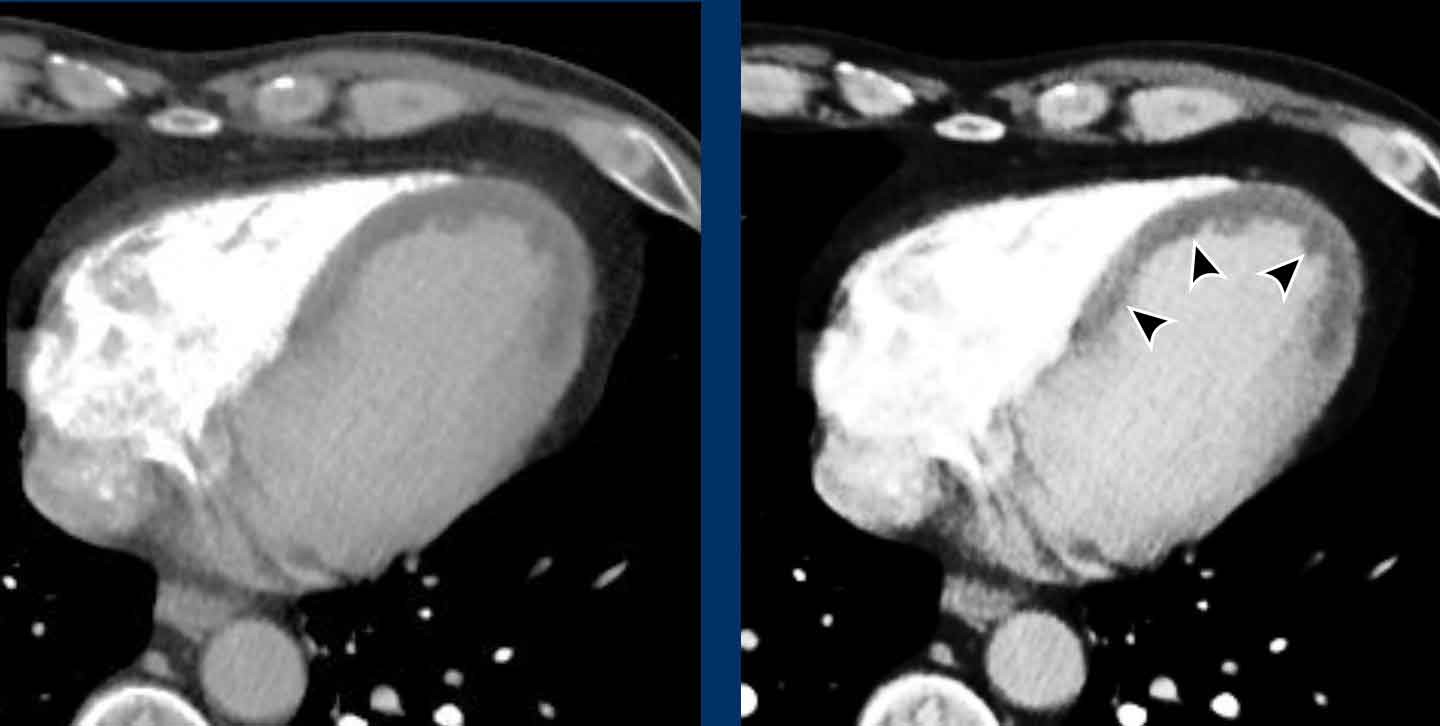

Images

The left atrium is dilated.

There is a thrombus in the left atrial appendage (arrow) extending towards the left atrium (arrowhead).

In the left atrial appendage there is often the imaging differential of a thrombus or incomplete opacification due to slow-flow, especially in early contrast phase imaging.

This might be solved with CT in a later contrast phase or acquisition in the prone position.

Transesophageal cardiac ultrasound is considered the gold standard.

Images

Slow-flow artefact in the

left atrial appendage, with inital incomplete opacification of the LAA but

complete filling in a later contrast phase.

Myxoma

A myxoma is a relatively rare benign tumor, but one of the commonest primary cardiac masses.

It usually originates in the atrium, mostly on the left side.

It is often pedunculated and attached to the interatrial septum.

They are heterogeneously low attenuating and calcification may be seen.

Depending on the size it may lead to valvular obstruction, prolapse and systemic embolic events.

Image

Incidental left-atrial myxoma.

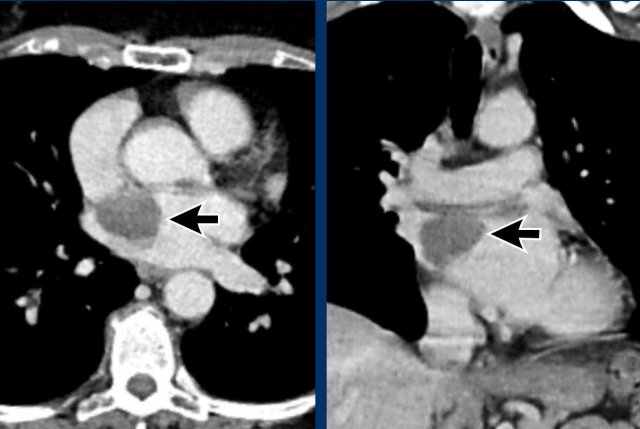

Cor triatriatum

In cor triatriatum the atrium is divided into two compartments by a fibromuscular membrane.

The membrane is more commonly seen in the left atrium.

The severity of clinical symptoms depends on the size of the fenestration in the membrane.

Less severe cases may go undetected for a long time.

Image

Incidental cor triatriatum sinistra with delayed opacification of the right compartment of the left atrium.

This was initially misinterpreted as a thrombus.

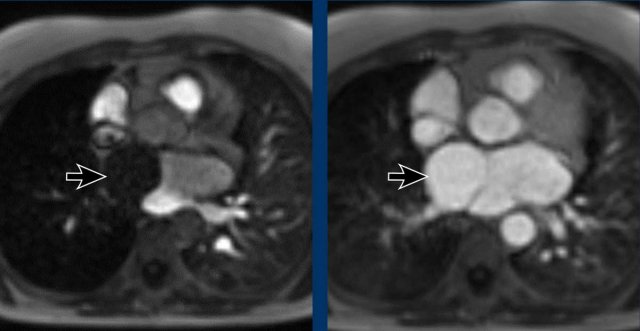

Continue with the MR...

Here the MR of the same case

Images

Delayed filling of the right compartment of the left atrium in a cor triatriatum sinistra.

Images

Less severe septation of the left atrium in cor

triatriatum, showing only a string-like structure that is also known as ‘left

atrial band’

Left Ventricle

Dilatation

The

left ventricle can be dilated due to various reasons, but most commonly due to

dilated cardiomyopathy, or post-infarction ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Decreased

systolic function of the left ventricle will lead to congestion, with left

atrial dilation, pulmonary edema and pleural effusions.

In the chronic situation, left heart disease and longstanding congestion may result in increased pressure on the right side of the heart, and eventually

cause pulmonary hypertension.

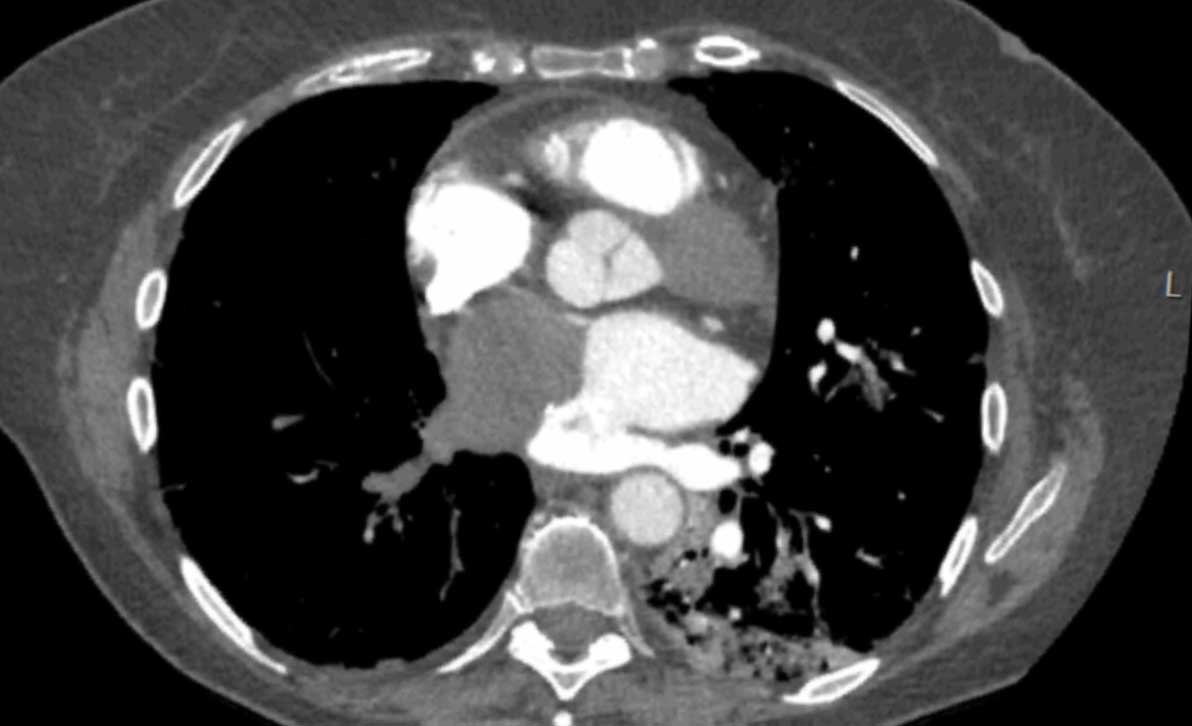

This image is of a female trauma patient, who presented with an intracranial hemorrhage.

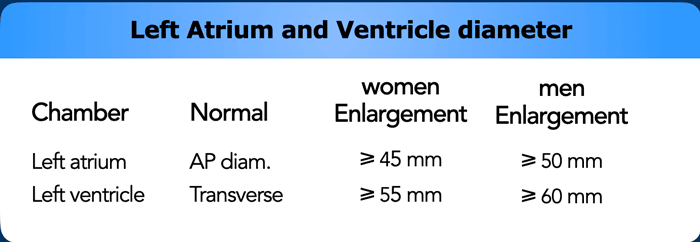

Image

Incidentally found severely dilated left ventricle.

The transverse LV diameter is > 70 mm.

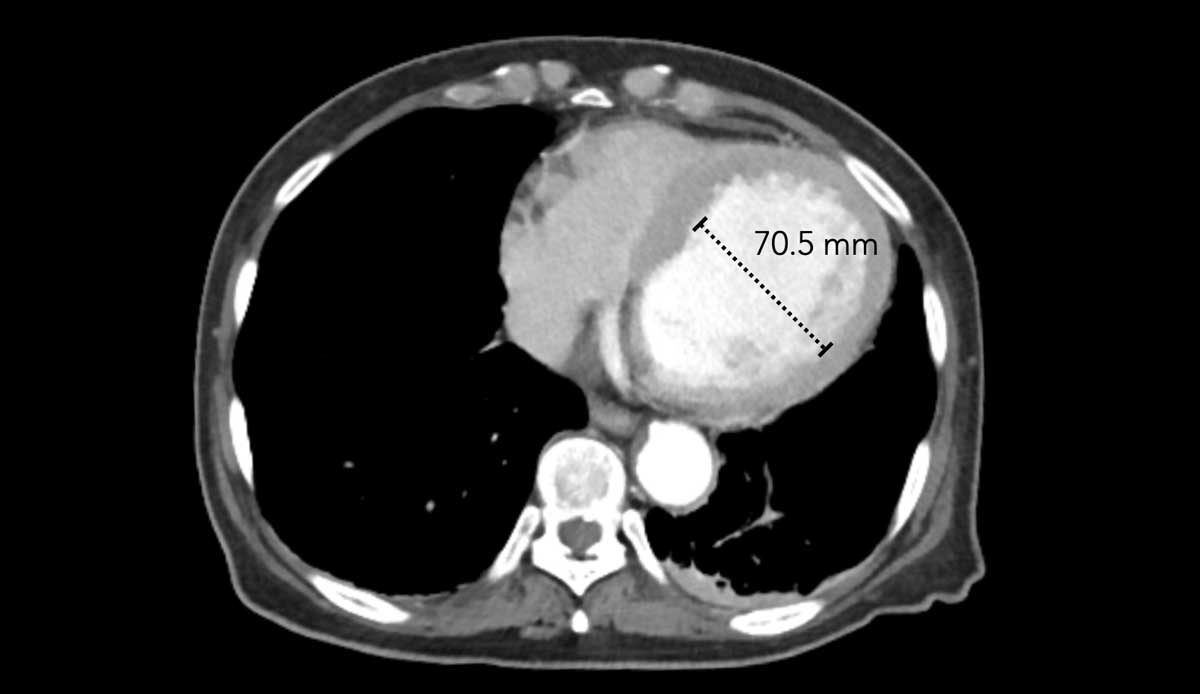

Hypertrophy

Myocardial dimensions are influenced by the time of acquisition,

as in systole the myocardium will appear thicker than in diastole. Nevertheless myocardial

hypertrophy should be suggested when thickness exceeds 20-25 mm.

Left

ventricular hypertrophy may either be concentric of asymmetrical:

- Concentric hypertrophy is a result of chronically increased workload, most commonly due to pressure overload in chronic hypertension or aortic stenosis.

- Asymmetric hypertrophy may result from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, where for example the basal septum is thickened and may obstruct the left ventricular outflow tract (HOCM).

- Other variants are also known, for example the apical hypertrophy variant.

Multiplanar

reconstructions can help to asses morphology of the myocardial hypertrophy, and

suggest possible underlying etiology.

Image

Concentric left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic

hypertension measuring up to 26 mm at the basal septum.

This is abnormal even in systole.

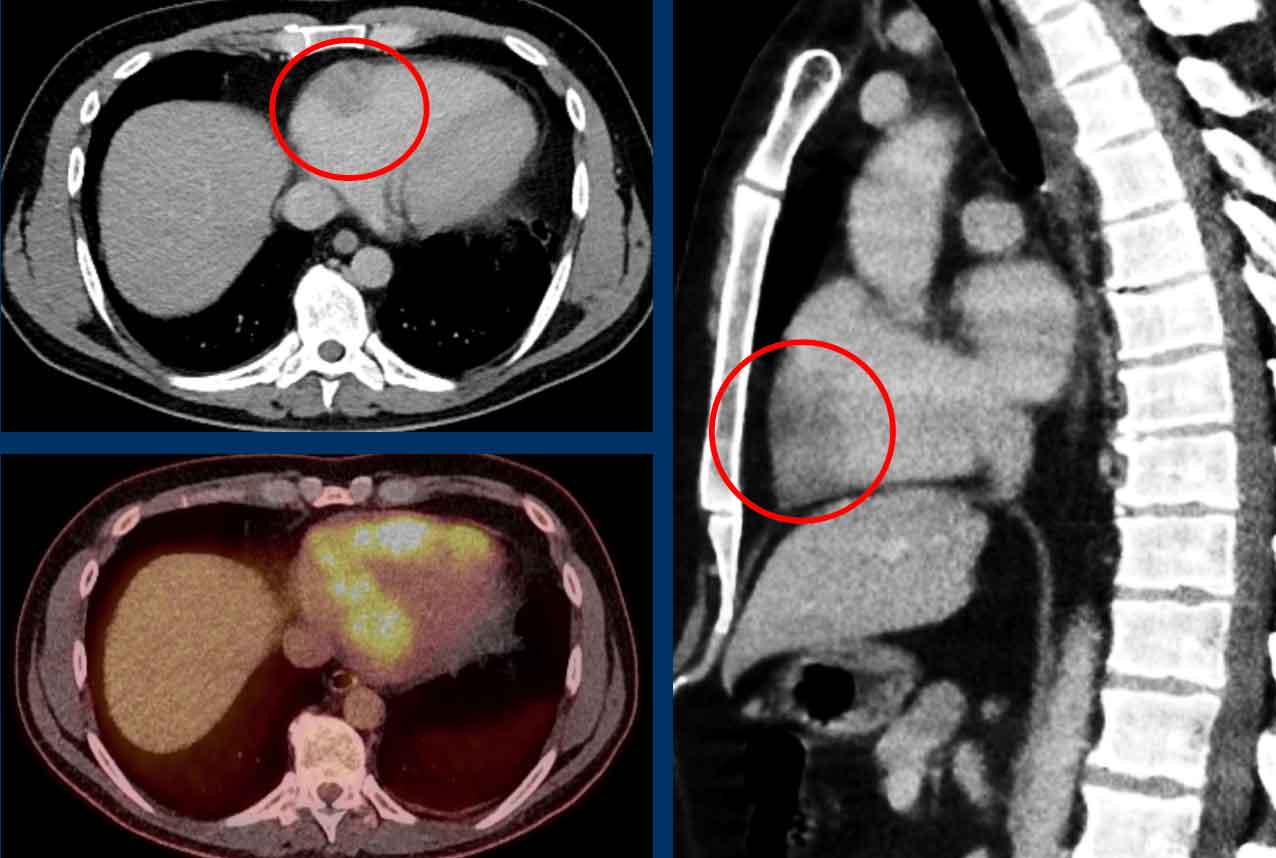

Myocardial infarction

A prior myocardial infarction may go undetected and signs of

such an event can incidentally be found on non-cardiac

chest CT.

Typically CT shows myocardial thinning with or without fatty

replacement, which is seen as a hypodense subendocardial line.

Image

Subendocardial fibro-fatty replacement after a prior infarction in the LAD territory.

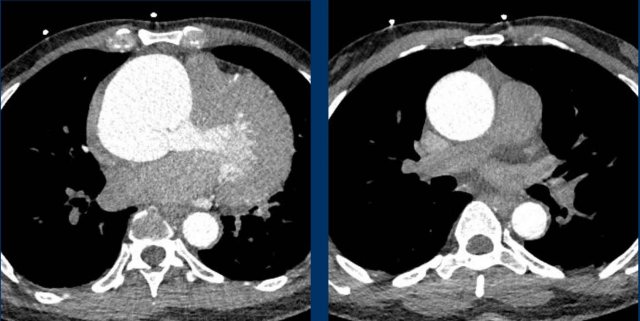

In the acute phase of a myocardial infarction a perfusion defect may be seen on contrast-enhanced chest CT as hypodense attenuation in a coronary territory.

This may present in scenarios where the patient's initial presentation is related to trauma – such as a traffic accident or fall from stairs – and the triggering cardiac issue is initially overlooked.

This scenario underscores the importance of a thorough evaluation of cardiovascular abnormalities in the early detection of unsuspected pathology.

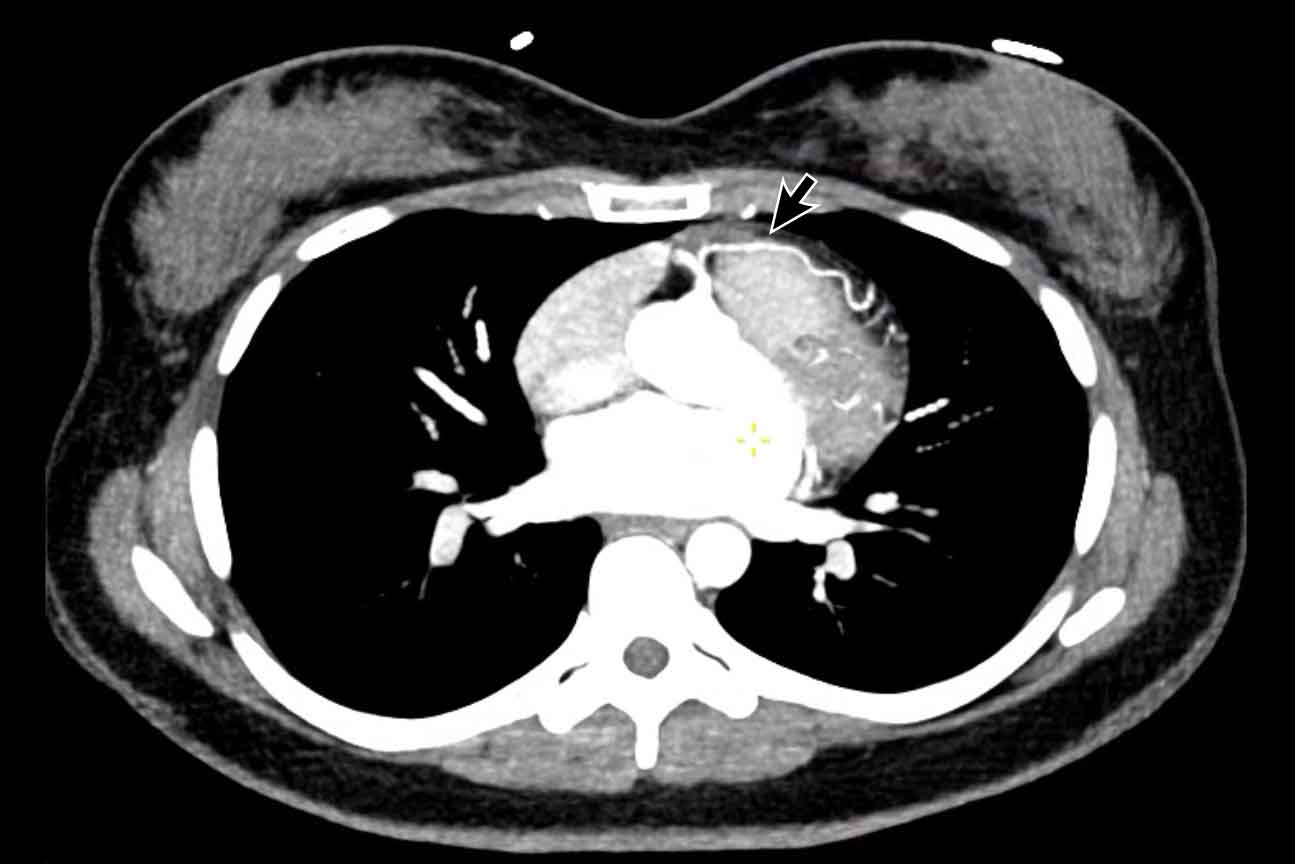

Image

Perfusion defect in LAD territory of 45 year old trauma patient, who presented after a fall from the stairs during heavy lifting.

A sharper window setting helps to assess the myocardial attenuation differences.

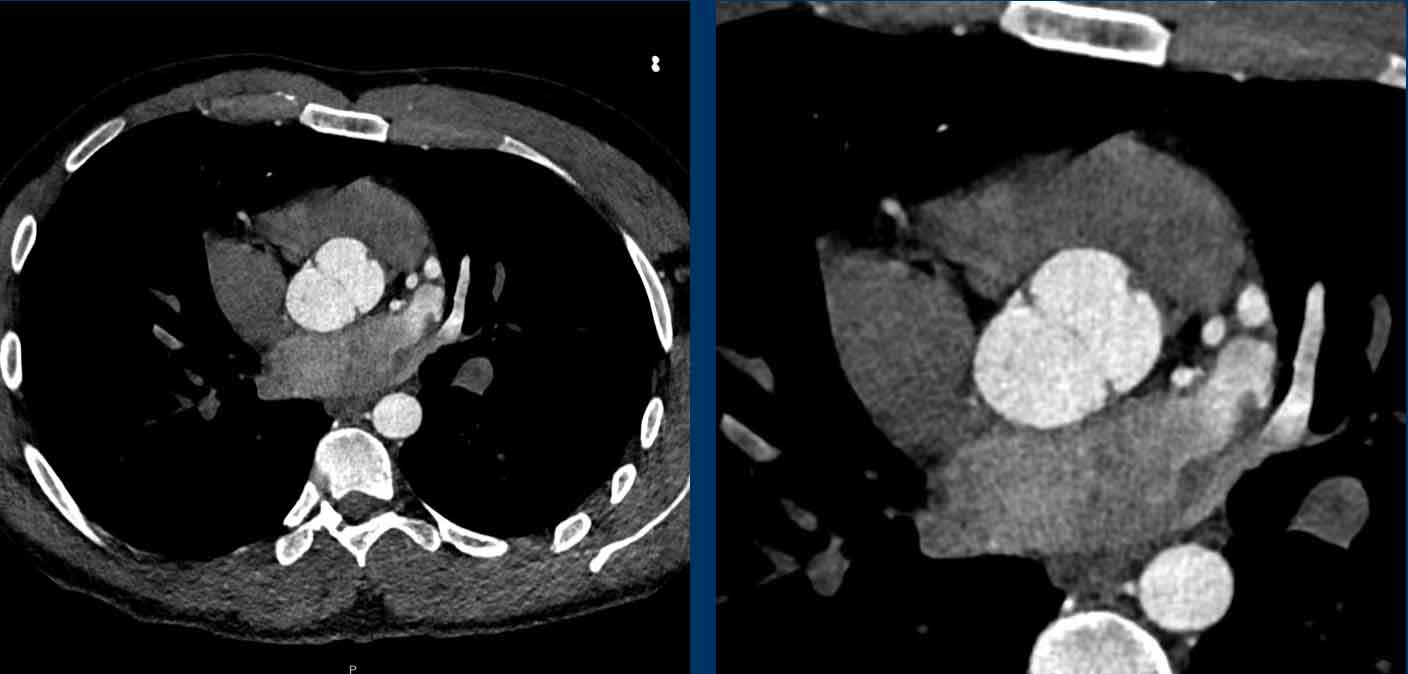

Aneurysm of the left ventricle

Aneurysmatic dilation of the left ventricular may develop

post-infarction, and sometimes shows wall

calcification.

Check for signs of an intracardiac thrombus in these cases,

as this can result in systemic emboli.

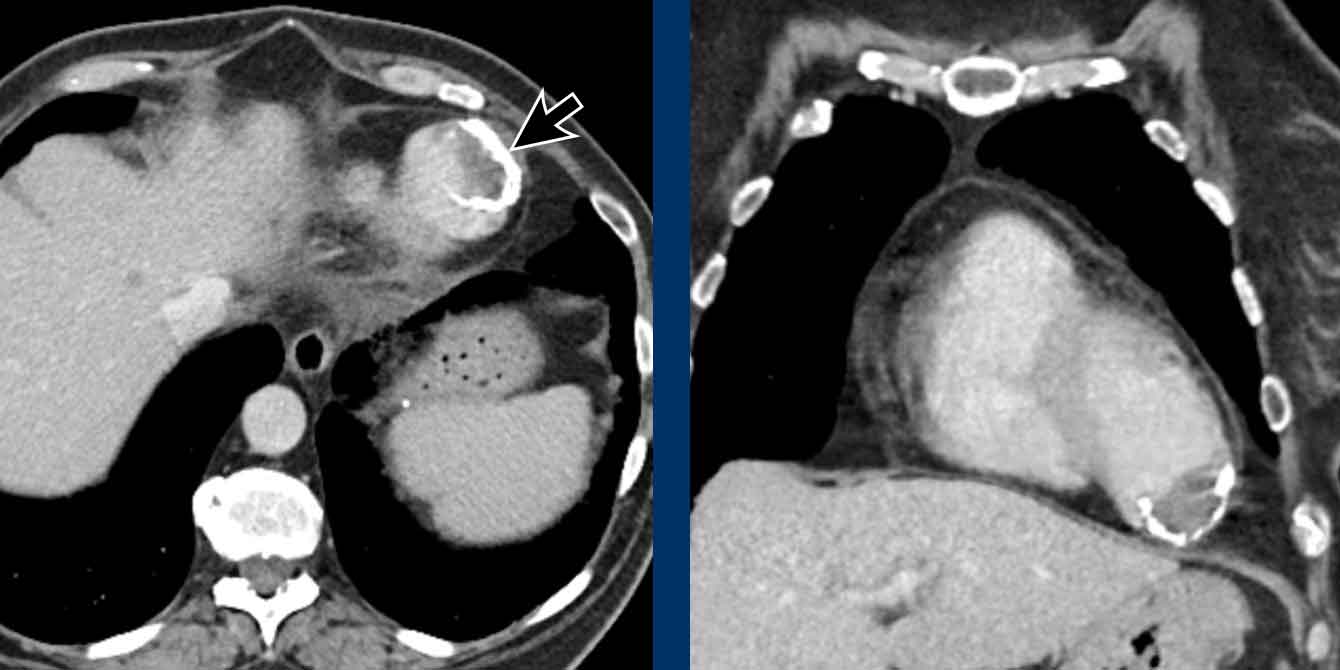

Image

Post myocardial infarction in LAD territory with apical

aneurysm formation, wall calcification and a large intraventricular thrombus.

Cardiac masses

Secondary malignancy due to metastatic spread is much more common than a primary cardiac tumor.

The ratio is estimated up to 30:1.

Image

Thickened nodular appearance of the heart apex (arrow) and a large pericardial effusion.

This was a metastatic disease from an ENT carcinoma.

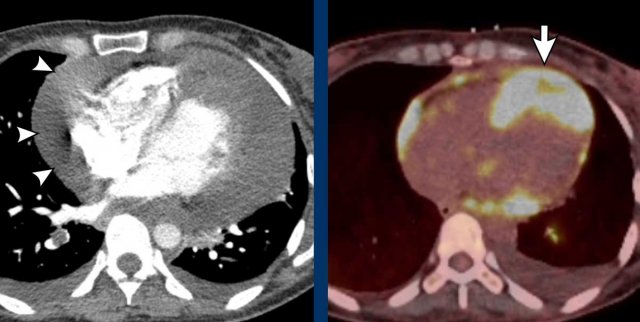

Image

Primary cardiac lymphoma

with involvement of the AV groove and right ventricle wall.

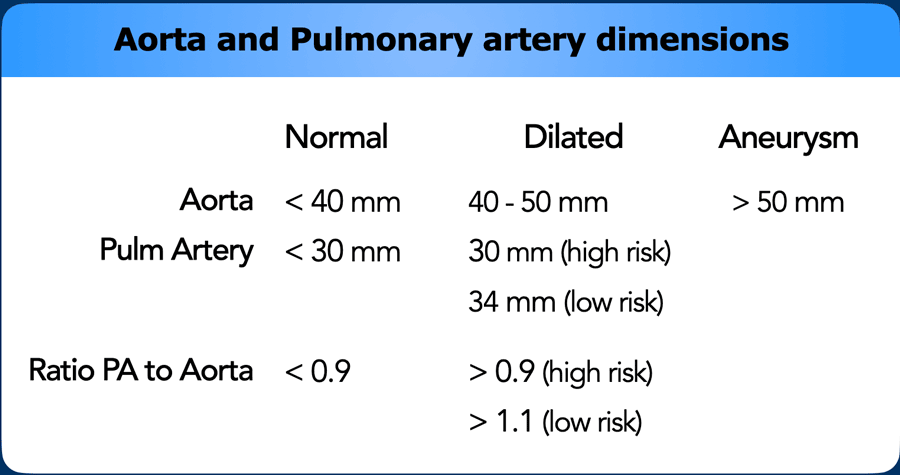

Aorta

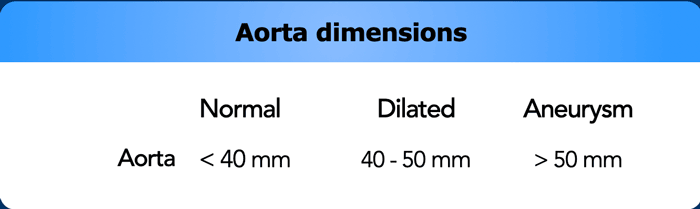

Aortic dilatation

The suggested cut-off values for defining an aortic aneurysm are 50 mm for the ascending and 40 mm for the descending aorta, with normal values approximately capped at 40 and 30 mm, respectively.

Values between normal and aneurysmatic should be considered dilated.

However, aortic size varies among patients, and individual values differ based on factors like age, sex, and body surface area.

Also, acknowledging the potential challenges in measurement accuracy due to factors like movement in non-ECG triggered CT imaging is important.

Nevertheless, taking into consideration the above mentioned margins of error it is important not to miss a significantly dilated aorta as there is increased risk of rupture, particularly in patients with a proximal aorta size exceeding 55 mm.

The threshold of determining the need for surgical intervention is lower in patients with known connective-tissue diseases such as Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos.

Image

Severe aneurysmatic dilation of aortic sinus and ascending

aorta.

When a dilated proximal aorta is seen, this should trigger more thorough evaluation of possibly associated abnormalities such as aortic valve stenosis or bicuspid aortic valve.

Image

Bicuspid aortic valve.

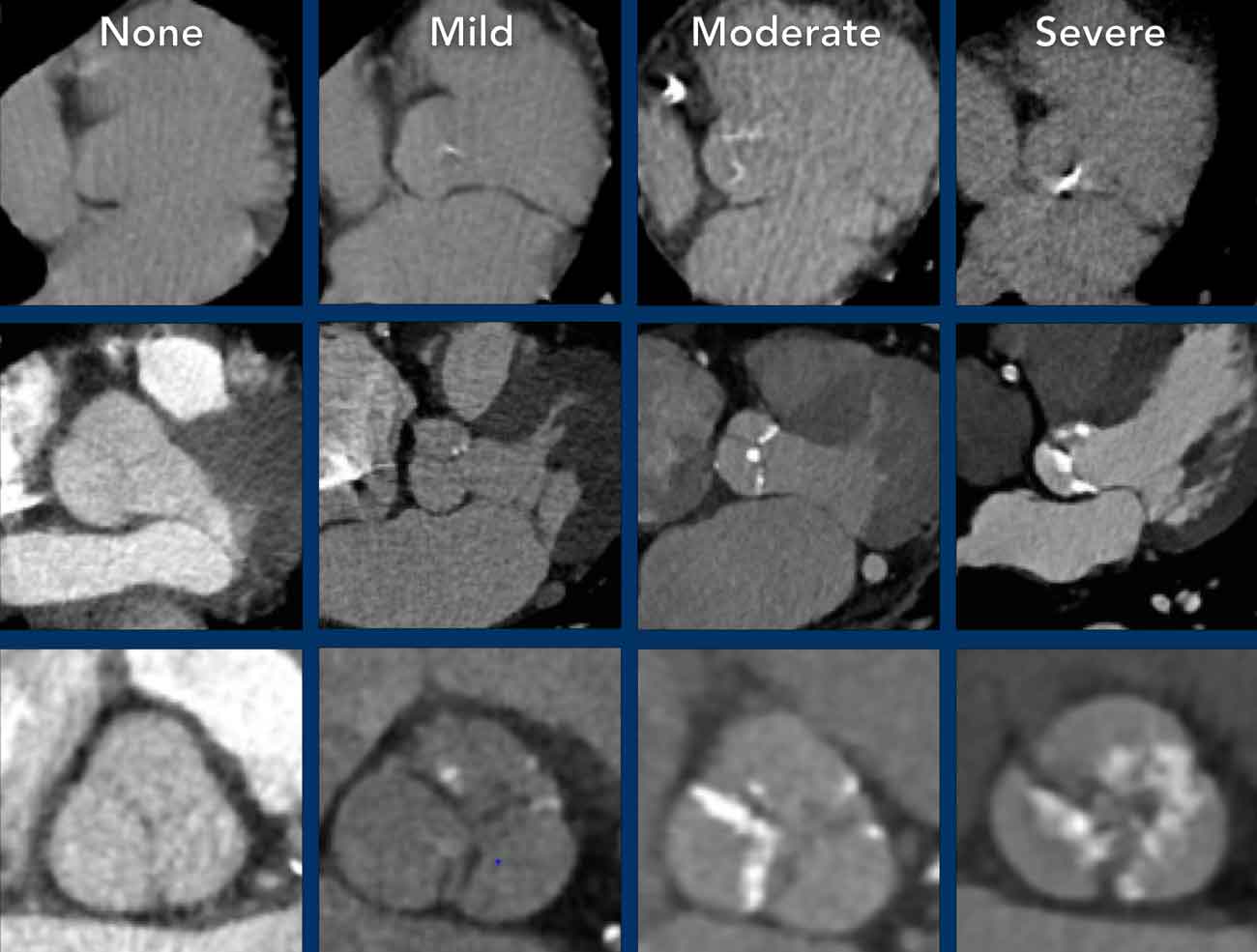

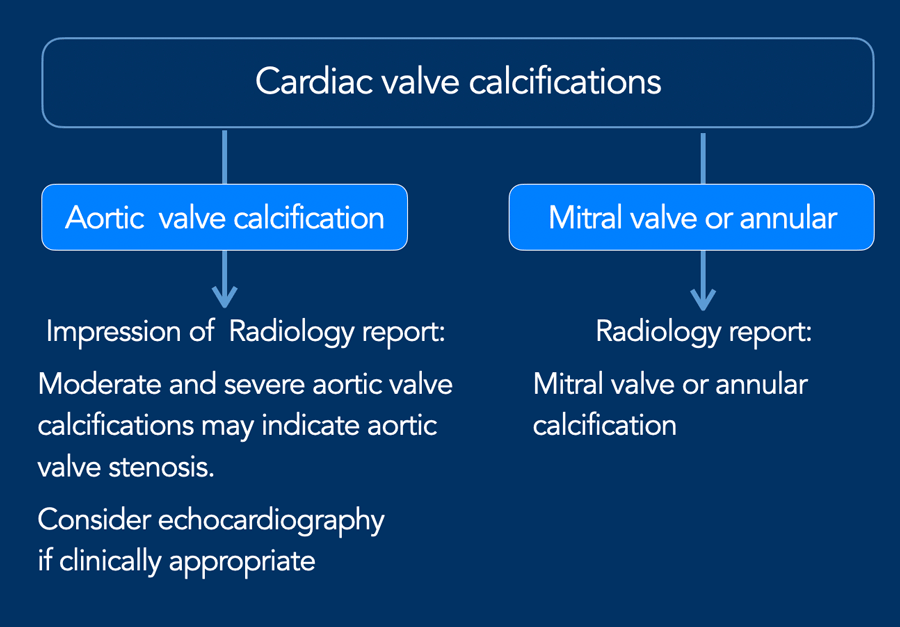

Aortic valve calcification

Aortic valve calcification is most often caused by calcific

degeneration and is therefore increasingly seen in older patients. In younger

patients a bicuspid aortic valve should be high in the differential diagnosis.

The extent of aortic valve calcifications correlate with the

severity of aortic stenosis.

It is recommended to visually quantify aortic valve calcification as mild, moderate and

severe (figure).

A recommendation can be included in the radiology report (see Figure).

If aortic valve calcification is identified, study the dimensions of the aortic root and ascending aorta.

Calcification may also occur elsewhere in the heart, including at the mitral valve or annulus, and in the pericardium. However, in many cases these are findings without clinical significance and require no recommendation in the report impression.

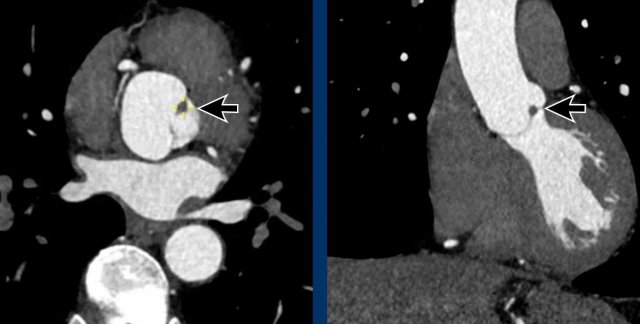

Papillary fibroelastoma of the Aortic valve

Non-ECG gated chest CT does not visualize the cardiac valves well, however, sometimes abnormalities can be seen.

As discussed above, main valvular incidental findings will be aortic valve and mitral calcification.

A rare finding is a papillary fibroelastoma (arrow), which is the commonest primary tumor in relation to the cardiac valves, mainly in relation to the aortic or mitral valve.

The typical CT finding of a PFE is a small irregular pedunculated mass in relation

to the heart valve.

Most often it is an asymptomatic incidental finding, although a

papillary fibroelastoma can be complicated by systemic embolic events.

Aortic arch and branch variants

Anomalies of the aorta and branches are discussed in the article 'Vascular Anomalies of Aorta, Pulmonary and Systemic vessels' by Marilyn J. Siegel and Robin Smithuis.

Aortic diverticulum

An aortic diverticulum is usually seen at the site of the isthmus where the ductal remnant or ligamentum arteriosum attaches.

Because this is also the location where the majority of traumatic aortic injuries is seen, it is sometimes mistaken for a pseudo-aneurysm.

A diverticulum shows more obtuse angles, often a more beak-like appearance and calcification may be present. Contrarily to an aortic injury, a diverticulum shows no irregularity and no surrounding infiltration or fluid.

Just distal to the level of the isthmus the aorta may show a more diffuse bulging, which is known as an aortic spindle. This is also a clinically irrelevant variant.

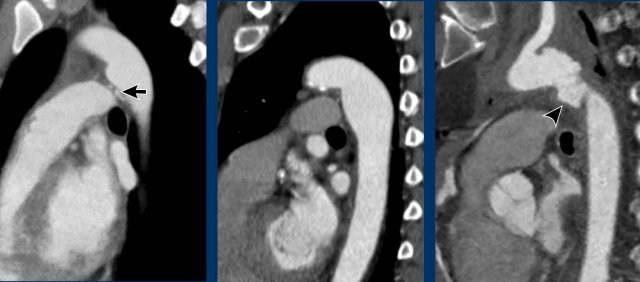

Images

Examples of an aortic diverticulum (left), an aortic splindle (middle), and traumatic aortic injury at the level of the isthmus.

Aortic branches including coronaries

Aberrant right subclavian artery

Also known as Lusoria artery, this is the most common aortic arch anomaly. Instead of being the first branch, the right subclavian artery originates distal to the left subclavian artery as the fourth branch. It then runs back towards the right side, its course variable in relation to the esophagus and trachea. In the majority of cases it runs posterior to the esophagus, but sometimes between the trachea and esophagus, or rarely even anterior to the trachea. Normally asymptomatic, it might result in trachea-esophageal symptoms, mainly dysphagia.

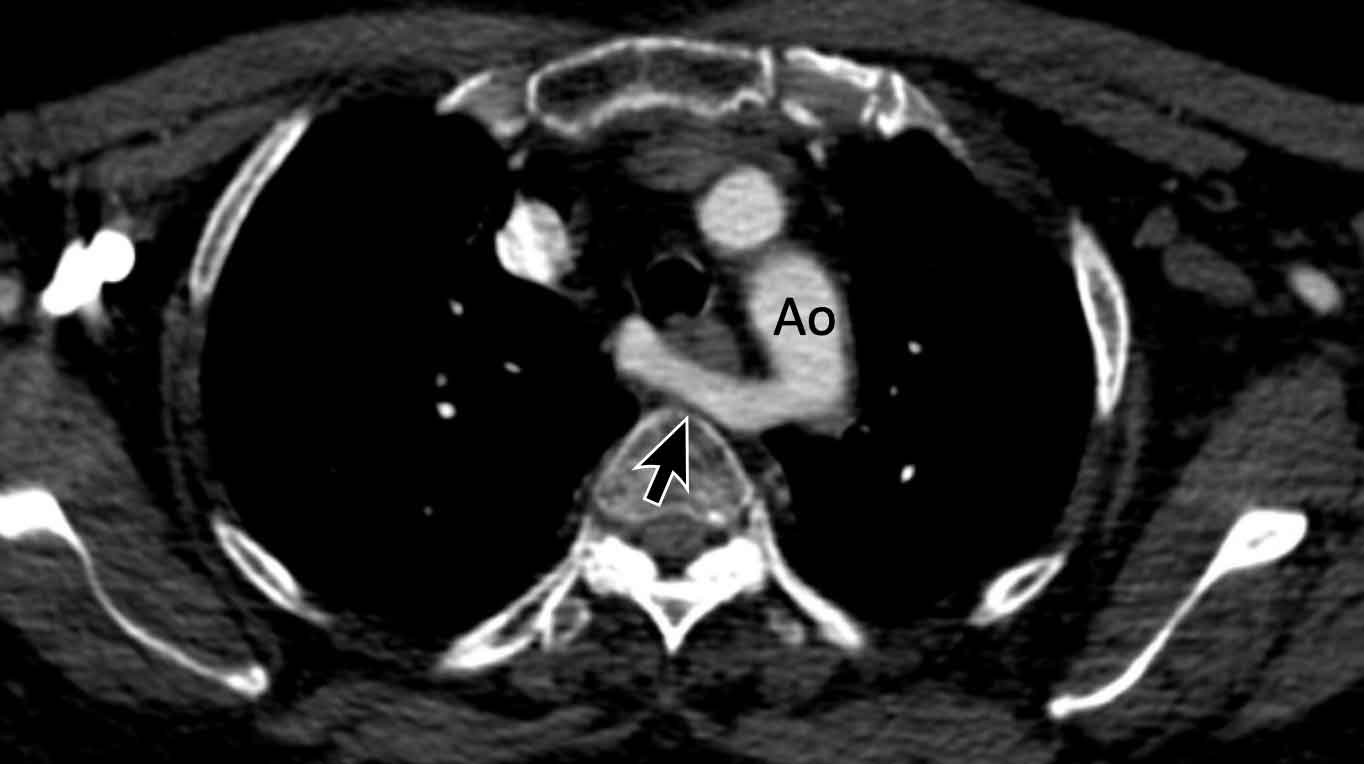

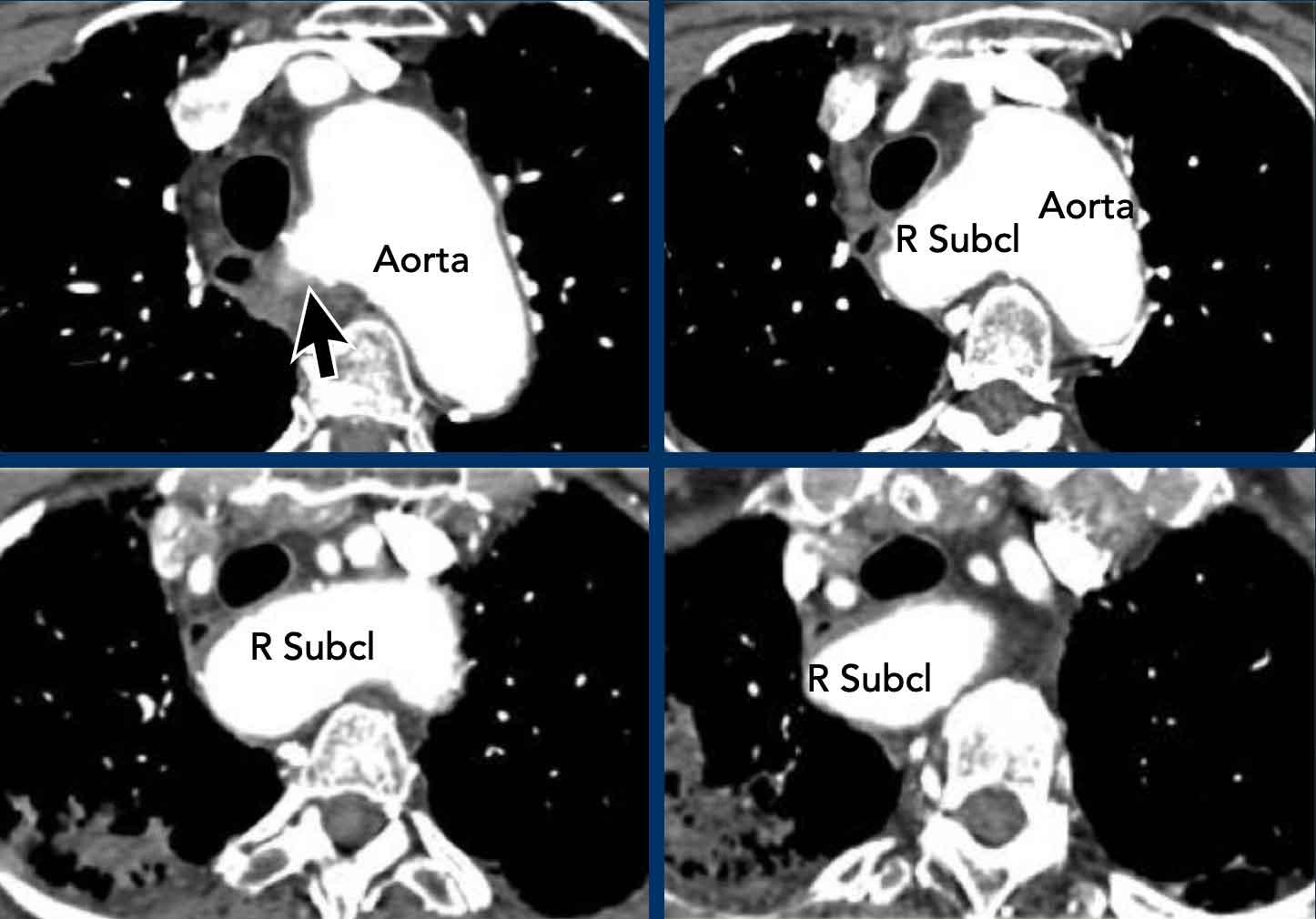

Images

Aberrant right subclavian artery with a retro-esophageal course.

Here a dilated aberrant right suclavian artery.

Notice the take off from the aorta behind the trachea and esophagus.

The dilatation results in swallowing problems due to obstruction of the esophagus.

Hypertrophy of bronchial arteries

The bronchial arteries deliver oxygenated blood under

systemic pressure to the supporting structures of the lung, including the

pulmonary arteries.

Although variation occurs, they

origin from the descending aorta mostly at the level of the fifth thoracic

vertebra.

Bronchial arteries are small and often not easily depicted.

When enlarged and sufficiently opacified they may be seen on chest CT.

Bronchial artery hypertrophy can be seen for

example in severe parenchymal disease and chronic thrombo-embolic

pulmonary hypertension.

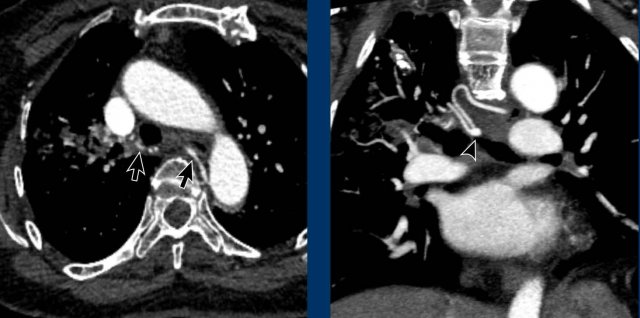

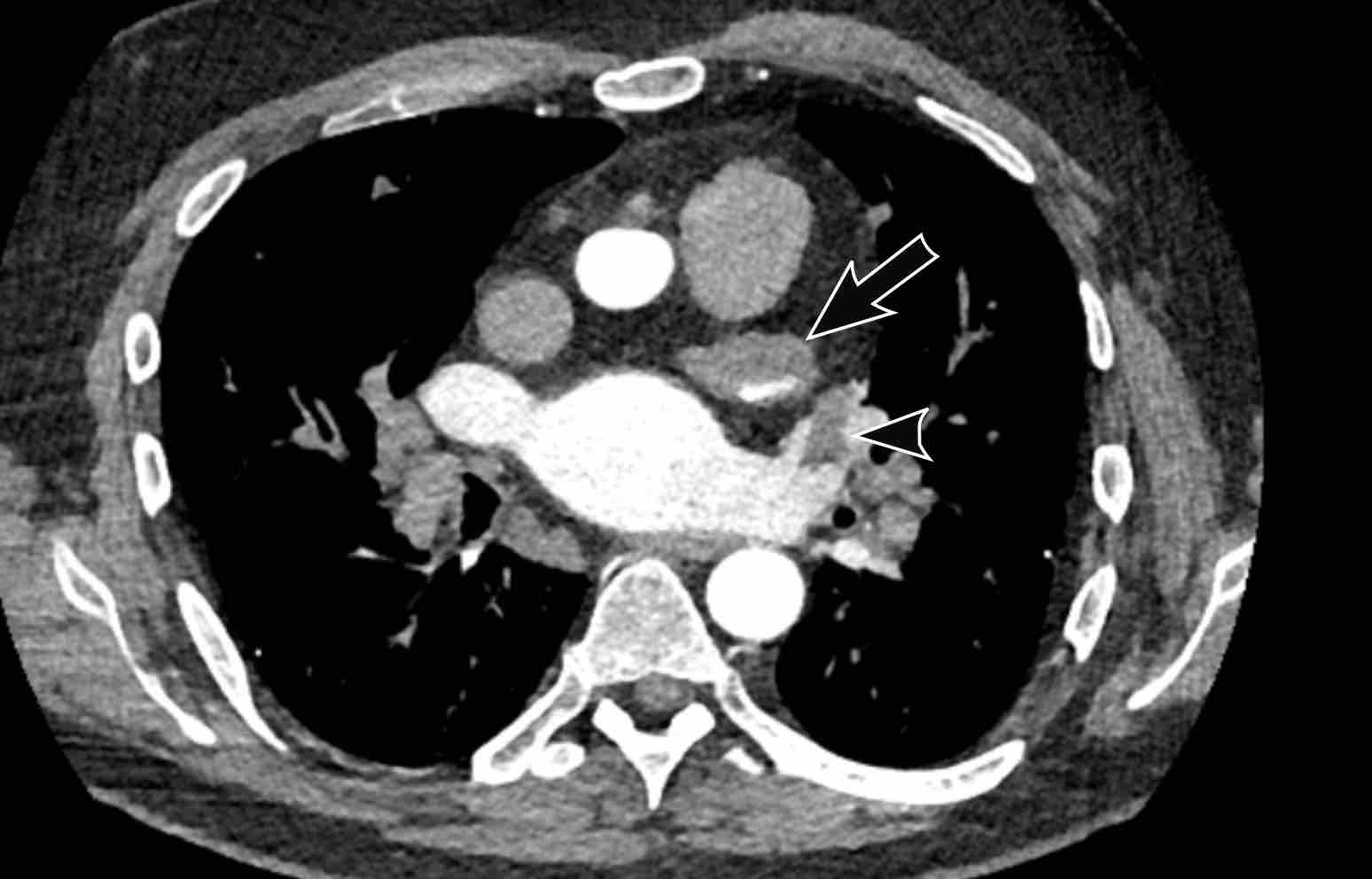

Images

Hypertrophy of the bronchial artery up to 4 mm in diameter (arrows) with a small aneurysm (arrowhead).

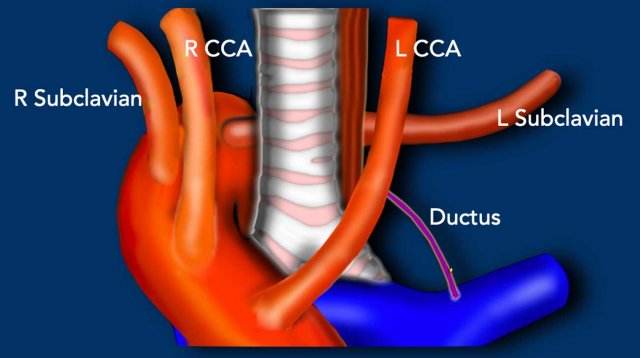

Persistent ductus arteriosus

The ductus arteriosus runs between the inferior aortic arch

at the level of the isthmus and the proximal left pulmonary artery.

Before birth it allows blood to bypass the non-ventilated

lungs in a physiologic right-to-left shunt.

The ductus normally closes in the early postnatal period.

Contrarily to the prenatal situation, a persistent ductus

after birth results in a left-to-right shunt with blood flowing from the

high-pressure systemic circulation into the low-pressure pulmonary artery.

This

leads to lung overcirculation and left heart volume overload.

The severity of the condition depends on the size of the shunt fraction.

Patency of the ductus may be isolated or associated with

other cardiac anomalies.

Images

Incidental patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) with a jet of less opacified blood (arrows) into the pulmonary artery.

Arch vessels

The arch

vessels can easily be assessed for proximal obstruction on contrast-enhanced CT

imaging.

Depending on which vessel is compromised this may have clinical

implications regarding perfusion of the brain (ie. carotids) or the upper

extremities (ie. subclavian arteries).

Image

Severe atherosclerosis in the proximal left

subclavian artery.

Proximal subclavian occlusion or severe flow obstruction may

explain a left-to-right difference in blood pressure, and is important

information for example to prevent a clinical suspicion for aortic dissection later in life.

Sequestration

In pulmonary sequestration there is a systemic arterial

supply of the involved segment of the lung.

This lung segment is not aerated and has per

definition no normal connection to the bronchial tree and pulmonary

arterial system.

Images

Systemic arterial supply to the left lower lobe in pulmonary sequestration.

Sometimes part of the lung parenchyma is supplied by a

systemic artery, either solely (ie. isolated) or in conjunction with normal pulmonary arterial supply (ie. dual

supply), while the bronchial anatomy and aeration of the involved lung segment is normal.

This

condition is named anomalous systemic arterial supply of the normal lung.

This is often an asymptomatic finding, but some

patients can develop focal hypertension with signs of congestion and

haemoptysis.

This may require surgical or endovascular intervention.

Images

Incidental anomalous systemic arterial supply of the normal posterobasal segment of the right lower lobe, without pulmonary sequastration. Note the subtle signs of congestion in the involved segment of the right lower lobe.

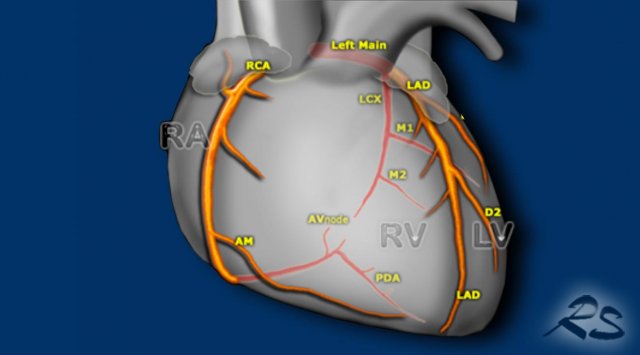

Aberrant coronary arteries

Large variation in origin and course of the coronary arteries exists.

Most are benign variants, but a proximal interarterial and intramural course (mostly RCA from left coronary cusp) is believed to carry an increased risk of ischemia, infarction and sudden cardiac death.

Within study limitations of non-cardiac chest CT one can check origin and proximal course of the coronaries to detect abnormalities.

Image

Benign course of an aberrant LAD originating from the right coronary artery (RCA), running anterior to the RVOT.

More anomalies of the coronary arteries are discussed in the article 'Coronary anatomy and anomalies' by Tineke Willems and Robin Smithuis

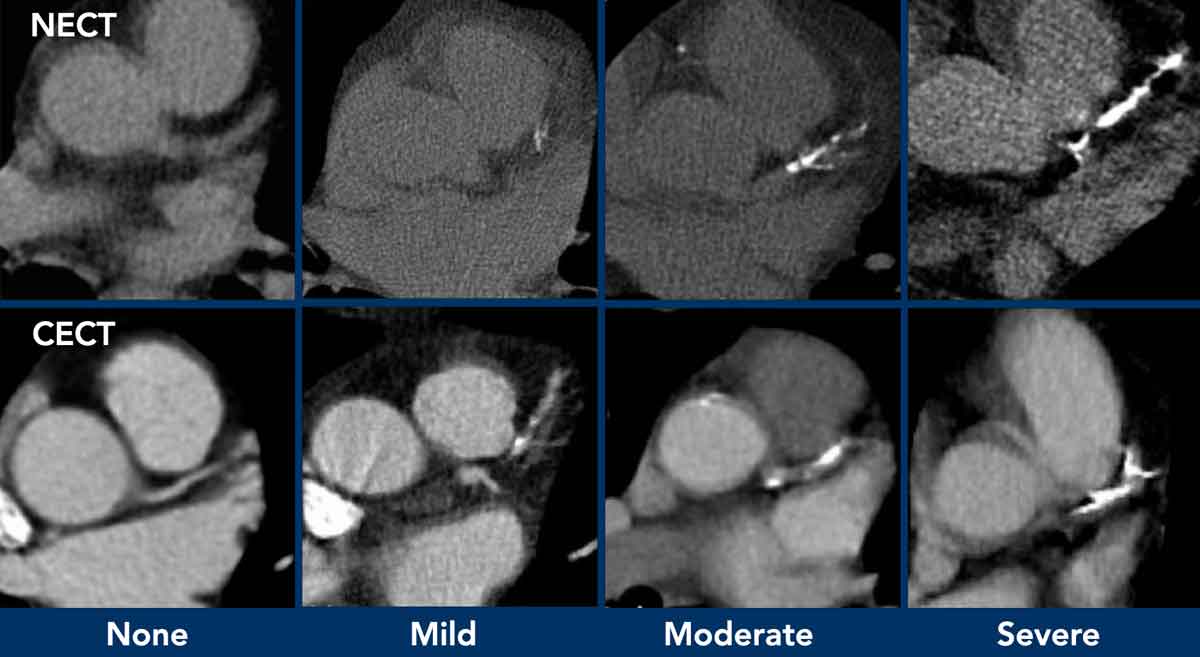

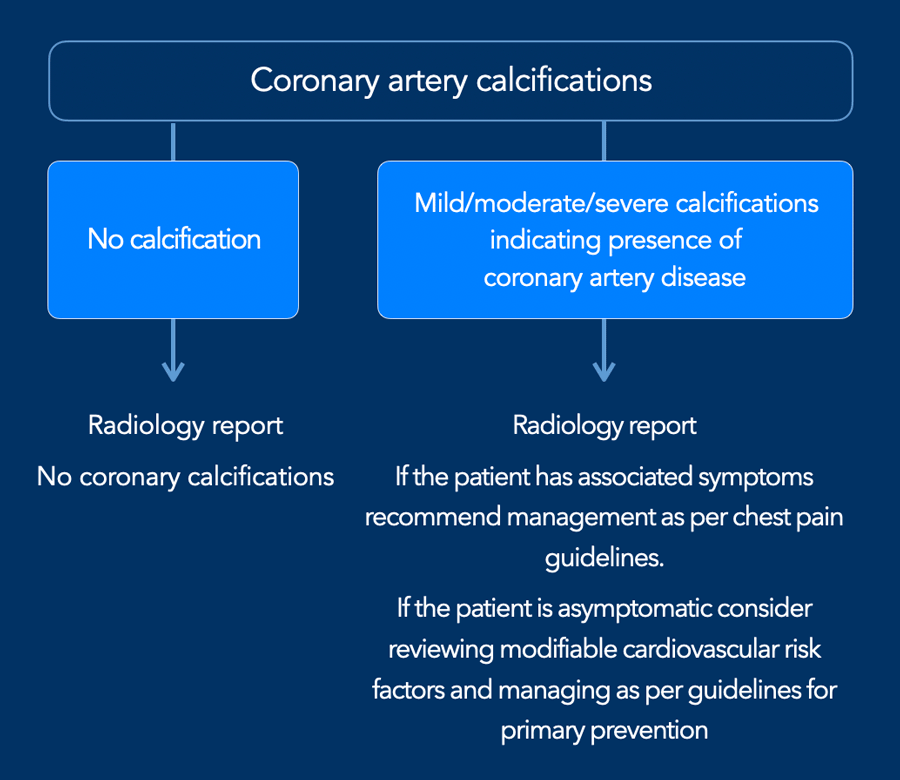

Coronary calcifications

Incidental coronary artery calcifications are a frequent

finding on non-cardiac chest CT.

There is now international

consensus that it is good clinical practice to comment on coronary

calcification as they are a marker of coronary artery disease.

The suggestion is to perform a simple visual

calcification score as None, Mild, Moderate or Severe, based on the cumulative findings

in all three coronaries (see Figure).

A recommendation may be added to the radiology report (figure)

When there are obvious signs of established coronary artery disease like the presence of a coronary stent or post-CABG changes, then assessment of coronary artery calcifications is not required.

Charity

All the profits of the Radiology Assistant go to Medical Action Myanmar which is run by Dr. Nini Tun and Dr. Frank Smithuis sr, who is a professor at Oxford university and happens to be the brother of Robin Smithuis.

Click here to watch the video of Medical Action Myanmar and if you like the Radiology Assistant, please support Medical Action Myanmar with a small gift.