Esophagus II: Strictures, Acute syndromes, Neoplasms and Vascular impressions.

Terrence C. Demos, MD, Harold V. Posniak, MD, Wayde Nagamine, MD and Mary Olson, MD

Department of Radiology of the Loyola University Medical Center, USA

Publicationdate

In Esophagus II we will discuss:

- Strictures

- Acute esophageal syndromes.

- Benign and malignant neoplasms.

- Vascular impressions.

Strictures

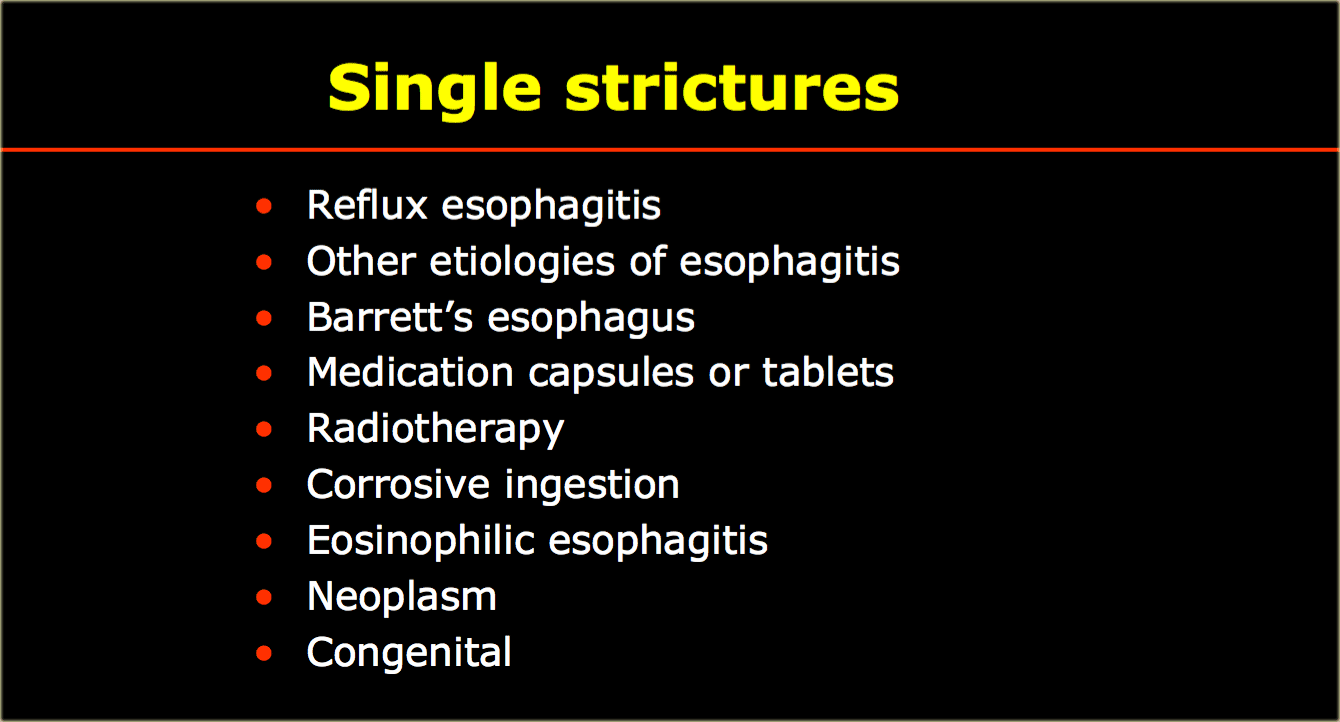

The table shows common and uncommon causes of esophageal strictures.

To the far left is an image of a stricture (arrow) with irregular mucosal folds at stricture site on air-contrast view.

This patient had Barrett's esophagus.

Mid esophageal strictures and ulcers are suspicious for Barrett's esophagus.

The two images on the right show a Barrett's esophagus with an irregular stricture due to adenocarcinoma.

Here an image of a long, symmetric tapered benign stricture months after radiotherapy.

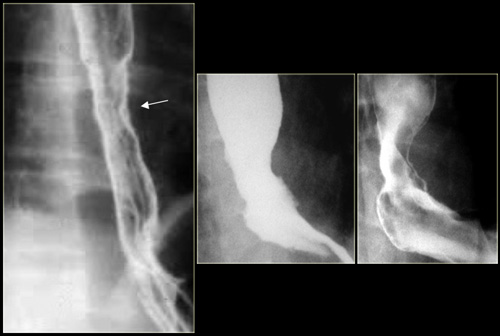

Here are images of a patient with a benign stricture high in the esophagus (arrow).

There is bilateral lower lobe lung consolidation due to repeated aspiration.

Approximately 5,000-15,000 cases of caustic ingestion occur in the US every year.

About 50%-80% occur in the pediatric population.

On the left a high stricture (arrow) following caustic ingestion

Osteophytes (arrow) can impinge on the esophagus and hypopharynx.

However they rarely cause symptoms.

Multiple structures are uncommon.

The table shows diseases that may present with multiple esophageal strictures.

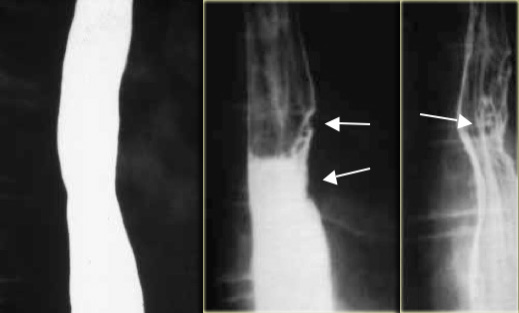

Here is an image of a patient with benign pemphigoid.

Mucosal bullae have led to multiple strictures (arrows).

This image is of a patient with benign epidermolysis bullosa.

Multiple strictures (arrows) are a residual of mucosal bullous disease.

Extensive bullous skin disease has led to webbed fingers and contractions.

Corrosive ingestion can result in multiple strictures.

Acute esophageal syndromes

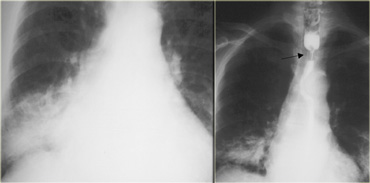

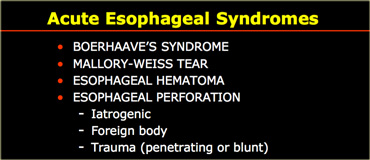

In the table on the left are etiologies of an acute esophageal syndrome.

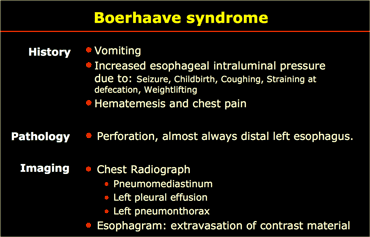

Boerhaave syndrome

Boerhaave syndrome is rupture of the esophageal wall.

It is most often caused by excessive vomiting in eating disorders such as bulimia although it may rarely occur in extremely forceful coughing or other situations, such as obstruction by food.

Boerhaave syndrome is a transmural or full-thickness perforation of the esophagus, distinct from Mallory-Weiss syndrome, a nontransmural esophageal tear also associated with vomiting.

These syndromes are distinct from iatrogenic perforation, which accounts for 85-90% of cases of esophageal rupture, typically as a complication of an endoscopic procedure, feeding tube, or unrelated surgery.

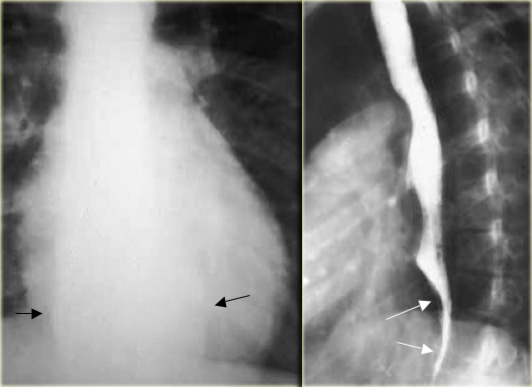

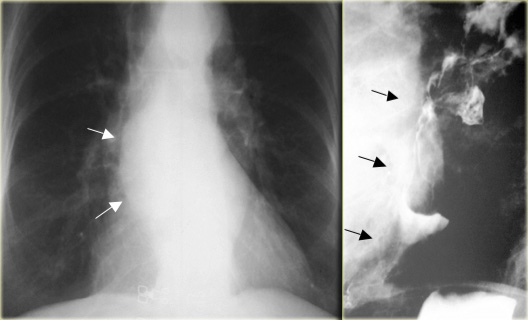

This image is of a patient with Boerhaave syndrome.

Chest radiographs show pneumomediastinum (arrows).

Esophagram with extravasated water soluble contrast material in left hemithorax (asterisk)

Perforation is almost always on the left side of distal esophagus.

Radiographs show mediastinal gas, effusion, and later pneumothorax.

Esophagram is used to confirm leak, first with water-soluble contrast, then barium if no leak is demonstrated.

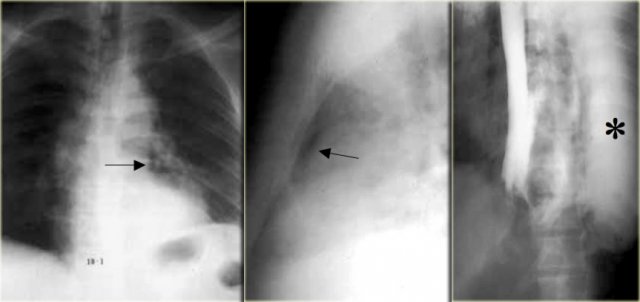

On the left a patient with Boerhaave syndrome.

The barium study shows extraluminal gas (arrow) without contrast extravasation.

CT shows extraluminal gas (arrows).

Rent of distal left esophagus confirmed at surgery.

CT can show small amounts of extraluminal gas or extravasation not visible on radiographs or esophagram.

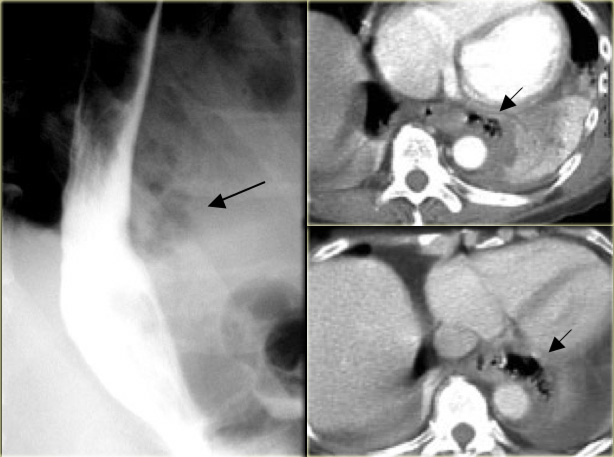

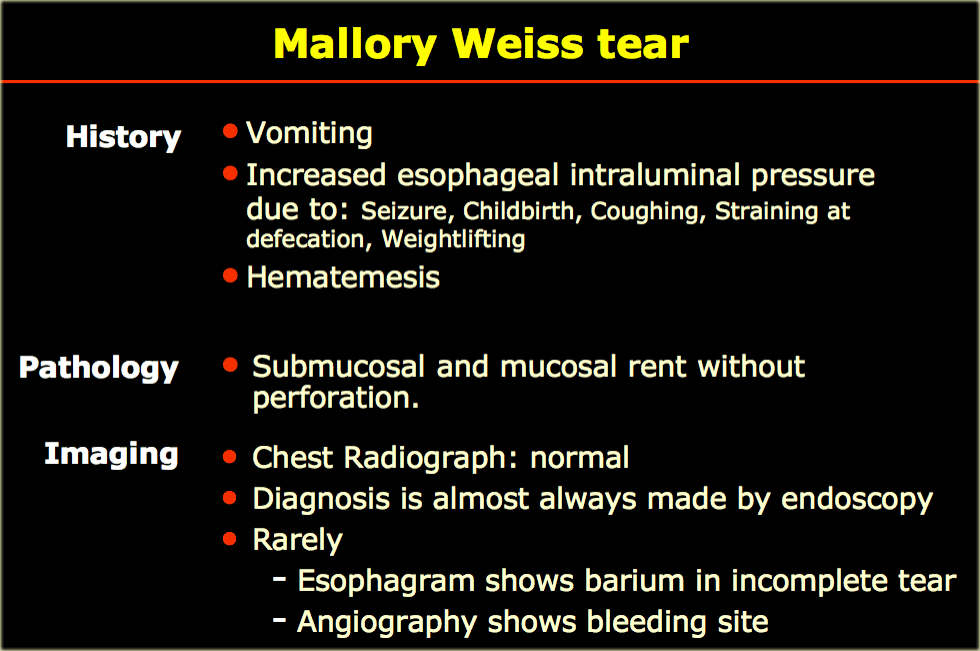

Mallory-Weiss tear

A Mallory-Weiss tear results from prolonged and forceful vomiting, coughing or convulsions.

Typically the mucous membrane at the junction of the esophagus and the stomach develops lacerations which bleed, evident by bright red blood in vomitus, or bloody stools.

It may occur as a result of excessive alcohol ingestion.

This is an acute condition which usually resolves within 10 days without special treatment.

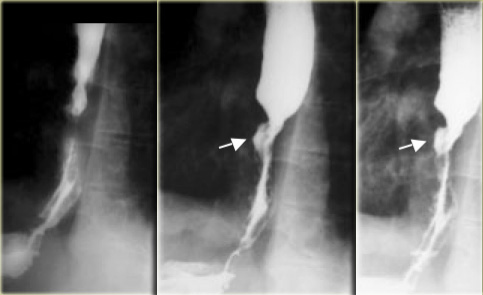

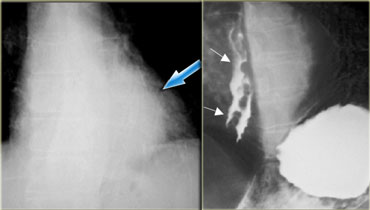

On the left a patient with a Mallory-Weiss tear.

Spot films show barium (arrows) in linear mucosal tear near gastroesophageal junction.

Tears may be in distal esophagus, gastric fundus, or extend across the GE junction.

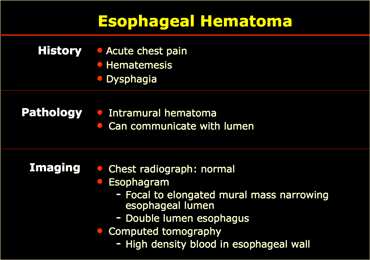

Esophageal hematoma

These unusual lesions have been associated with increased esophageal

intraluminal pressure, most often vomiting, instrumentation, and anticoagulation

or bleeding disorders.

Some are spontaneous.

Blunt trauma is a rare cause.

Hematomas are self-limited and almost never progress to perforation.

Most esophageal hematomas resolve in 1-2 weeks with conservative treatment.

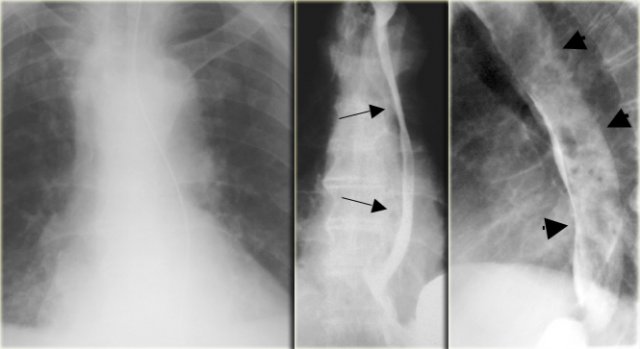

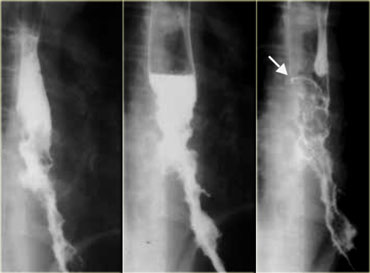

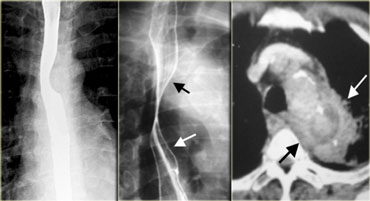

On the left a patient with an esophagus hematoma.

He presented with chest pain and dysphagia after vomiting.

Aside from tortuous aorta chest radiograph is normal.

The barium study shows a narrowed lumen (arrows) on AP view and flattened lumen on lateral view (arrowheads) suggestive of a intramural hematoma.

On CT the diagnosis of an intramural hematoma was confirmed.

A high density mural hematoma (arrowhead) is seen next to NG tube (arrow).

Following conservative treatment, six months later the barium study was normal.

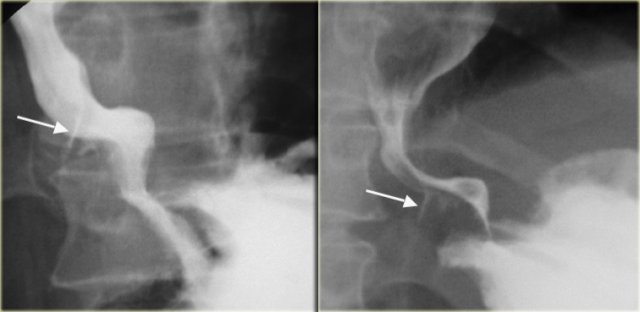

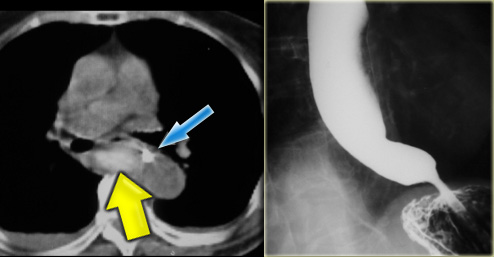

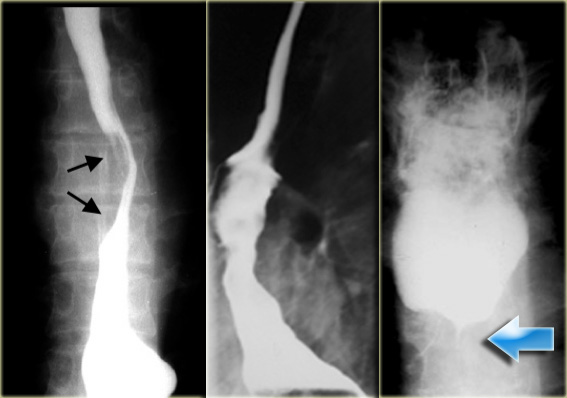

On the left a patient who had a complicated endoscopy.

Instrumentation caused a mucosal tear and dissecting intramural hematoma resulting in double lumen with separating stripe of mucosa (arrows).

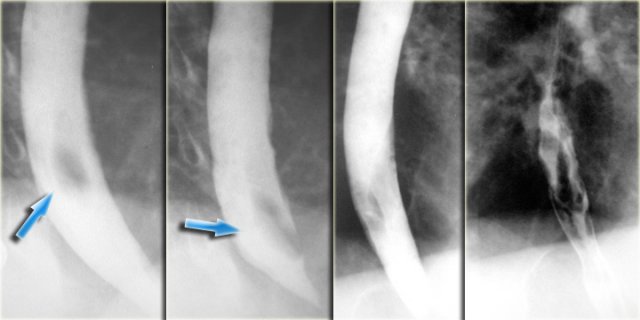

On the far left an intramural extravasation (arrow) after distal dilation for achalasia.

In the middle an intramural extravasation (arrow) after complicated endoscopy.

On the right a perforation after biopsy with extravasation of contrast material (arrow).

Benign neoplasms

Here a list of benign esophageal masses.

Leiomyomas

Leiomyomas are the most common benign esophageal neoplasm and are often large yet nonobstructive. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are least common in the esophagus.

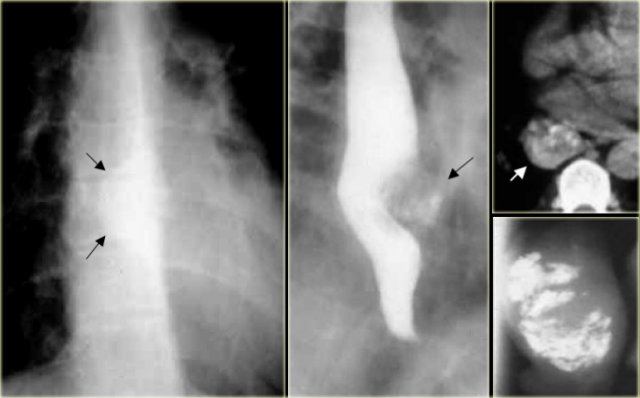

On the left an asymptomatic patient with a leiomyoma.

On the chest film an abnormal opacity is seen behind the heart (arrow).

The barium study demonstrates a lobulated mass (arrow) that does not obstruct despite its large size.

Mucosal lesions are indicated by mucosal irregularities.

Submucosal intramural lesions produce smooth filling defects, and in profile, the margins often form close to a right angle with the esophageal wall.

Extrinsic lesions tend to form longer obtuse angles if not fixed to the esophageal wall, and their epicenter may be outside the esophagus. In practice, the location of a lesion may be difficult to determine.

On radiograph, tumor (arrows) protrudes into azygoesophageal recess.

On esophagram, the inferior margin of this intramural lesion forms close to a right angle (arrow) with esophageal wall.

A calcified esophageal mass is almost always a leiomyoma.

On the left a patient with a calcified esophageal lesion (arrows) protrudes into azygoesophageal recess on radiograph.

Lesion (arrow) on CT and surgical specimen radiograph showing calcification.

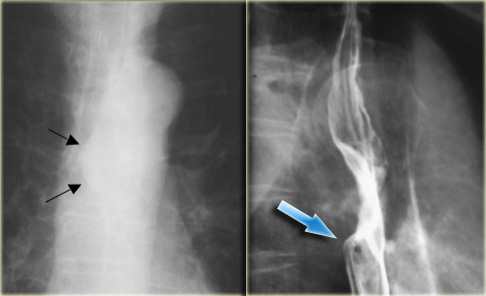

On the left a patient with granular cell myoblastomas, an uncommon benign tumor.

These two lesions (arrows) are nonspecific in appearance, but the proximal lesion does demonstrate overhanging and right angle margins indicating mural location.

Fibrovascular polyp

Pedunculated fibrovascular polyps are rare lesions, that are difficult to diagnose on esophagrams.

Their movement during the examination produces an inconstant position.

Their shape may be suggestive as in this patient.

The stalk is often difficult to identify.

Duplication

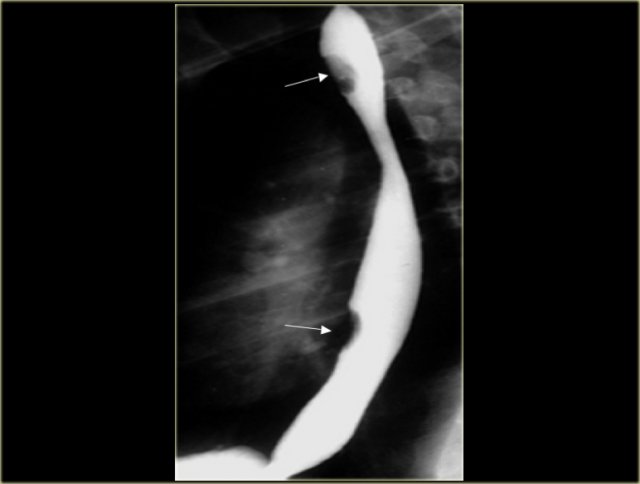

On the left a patient with an esophageal duplication.

The findings on the barium study are non-specific.

Lesion (arrows) is visible behind the heart on radiograph.

Esophageal narrowing (arrows) is caused by duplication.

A foregut duplication cyst is a congenital cyst.

In the case on the left it displaces hypopharynx and opacified esophagus (arrow) posteriorly and trachea and larynx (asterisk) anteriorly.

Malignant neoplasms

Here a list of malignant esophageal masses.

Early and small esophageal carcinoma are not synonymous.

Early esophageal carcinoma is limited to the mucosa, submucosa with no lymph node metastases.

Most are small ( Small esophageal carcinoma is defined by the size of the lesion, a diameter So an early carcinoma may be small, but a small carcinoma may be invasive or metastatic and thus not an early carcinoma.

This image is of a patient with an early esophageal carcinoma.

Lesion is not visible on single contrast esophagram.

Air-contrast esophagram shows surface irregularity (arrows) indicating a mucosal lesion.

This was both a small lesion and a pathologically early squamous carcinoma.

Advanced carcinoma has many gross appearances:

- Polypoid

- Varicoid

- Infiltrative

- Ulcerative

- Superficial spreading

- Stricture

- Pseudoachalasia

On the left two cases of polypoid carcinoma.

Esophageal carcinoma with ulcerations (arrows) and sharp right angle junction with esophageal wall (arrowheads)

Esophageal carcinoma with ulcerations (arrows) and sharp right angle junction with esophageal wall (arrowheads)

This image is of a patient with an infiltrative ulcerated carcinoma.

This lesion has an abrupt transition forming an acute angle and overhanging edge.

This indicates mural involvement and is different than obtuse angles usually produced by extrinsic lesions that are not fixed to the esophagus.

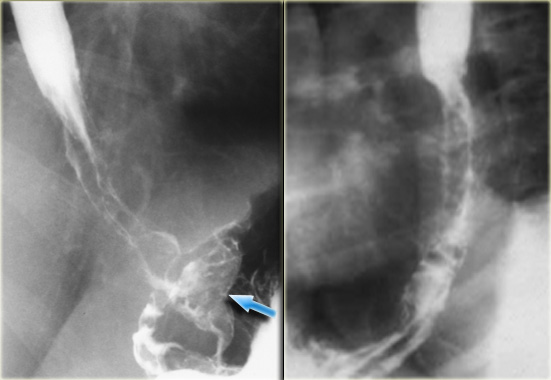

These images are of a patient with a varicoid carcinoma.

Unchanging appearance of filling defects indicate tumor rather than varices.

Note sharp upper margin of lesion and ulceration (arrows)

To the far left an image of a patient with a varicoid carcinoma.

Long lobulations simulate varices but did not vary during fluoroscopy.

Note large irregular folds and soft tissue mass (arrow) of gastric fundus

Next to it an image of a patient with a superficial spreading carcinoma.

Extensive superficial spread involves distal esophagus.

This appearance can be seen with both early and advanced lesions.

LEFT: Long irregular distal stricture due to carcinomaRIGHT: Distal narrowing is not tapered and more proximal than achalasia. Irregularity (arrow) at narrowed site is subtle but persistent

LEFT: Long irregular distal stricture due to carcinomaRIGHT: Distal narrowing is not tapered and more proximal than achalasia. Irregularity (arrow) at narrowed site is subtle but persistent

On the far left a patient with a carcinoma with stricture.

An irregular, asymmetric stricture is highly suggestive of carcinoma.

Smoothly tapered, symmetric strictures are characteristic of a benign etiology, but malignant strictures can have similar characteristics and mimic benign lesions.

Next to it a patient with a carcinoma with stricture resembling achalasia.

Distal esophageal malignancy may closely resemble achalasia.

If esophageal motility is normal, achalasia can be excluded.

If abnormal, however, subtle imaging features; asymmetric, irregular, abrupt, or high narrowing, mucosal abnormality, or fixed abnormality suggest diagnosis.

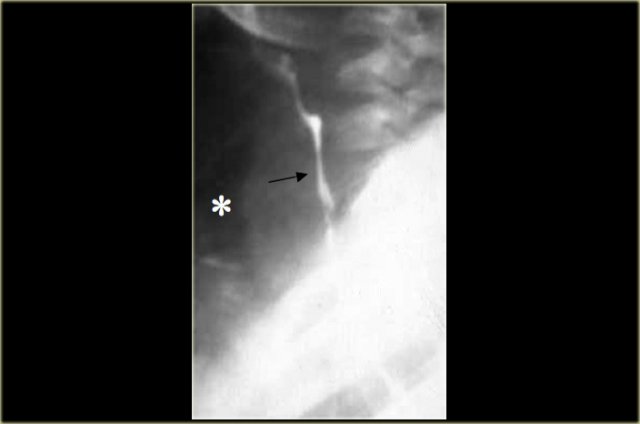

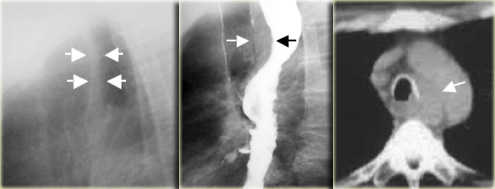

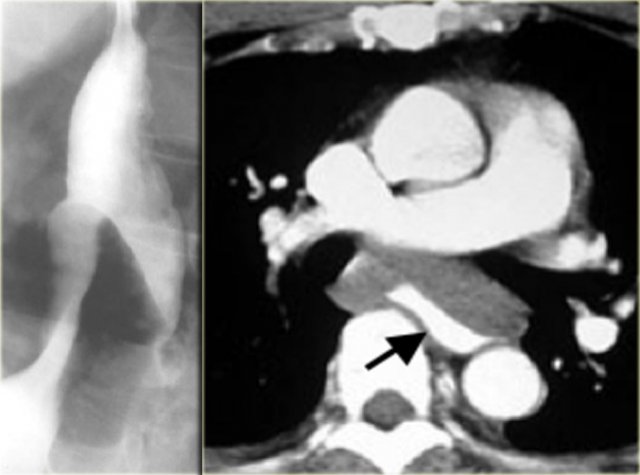

On the left another case of pseudoachalasia.

Distal narrowing simulates achalasia, but narrowing is eccentric, shoulders are asymmetric (arrows), and the mucosa is irregular at the tip of narrowing.

CT shows gastric fundus thickening (arrows) due to adenocarcinoma.

Tracheoesophageal stripe

Width of the juxtaposed posterior tracheal and anterior esophageal walls > 5 mm on a lateral chest radiograph is suspicious for pathology, most often esophageal carcinoma or achalasia.

On the left a patient with a widened 1 cm stripe (arrows).

Esophagram shows widened stripe (arrows) and irregular margins of midesophageal carcinoma.

CT shows abnormal soft tissue dorsal to trachea.

The tumor invades mediastinum adjacent to aortic arch (arrow)

Barrett's esophagus and Adenocarcinoma

Barrett's esophagus is a proven risk factor for the development of an adenocarcinoma.

The incidence of cancer in Barrett's however is controversial.

Who, how, and when individuals should be screened is unresolved.

Adenocarcinoma was 10% of esophageal malignancies in 1960s.

Since 1960s, incidence increasing in USA greater than any other carcinoma.

Incidence now approaching or exceeding squamous carcinoma in Caucasian men in the USA and Europe.

On the left a patient with an ulcerated (arrow) plaque like adenocarcinoma in a Barrett's esophagus.

Primary gastric fundus adenocarcinoma can invade the esophagus, but means of differentiating invasion from a primary esophageal tumor are a subject of debate.

On the left a patient with a gastric fundus adenocarcinoma.

The barium study demonstrates marked irregular thickening of distal esophagus and folds at gastroesophageal junction.

CT shows thickened irregular lesser curvature wall (arrows) near gastroesophageal junction.

Spindle cell carcinomas are rare neoplasms, also called carcinosarcomas.

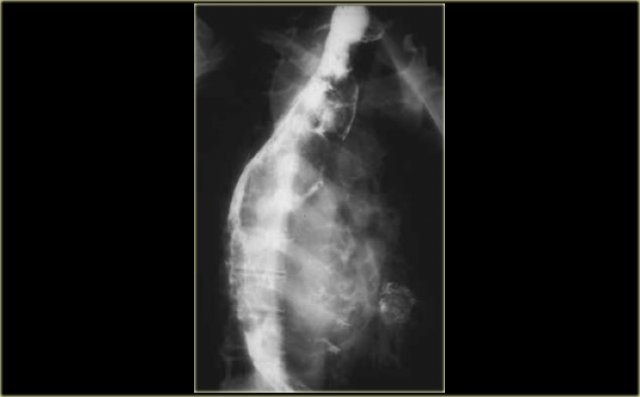

They are often bulky but nonobstructive as in the case on the left.

Leiomyosarcomas and rare primary melanomas of the esophagus also tend to be bulky but do not cause significant obstruction.

On the left a patient with a leiomyosarcoma of the esophagus.

Margin (arrows) of bulky lesion visible on chest radiograph.

Lateral view of esophagram shows marked irregularity and esophageal narrowing (arrows).

On the left another patient with a leiomyosarcoma of the esophagus.

Large lesion distorts esophageal lumen.

CT shows lesion distorting but not obstructing esophageal lumen (arrow).

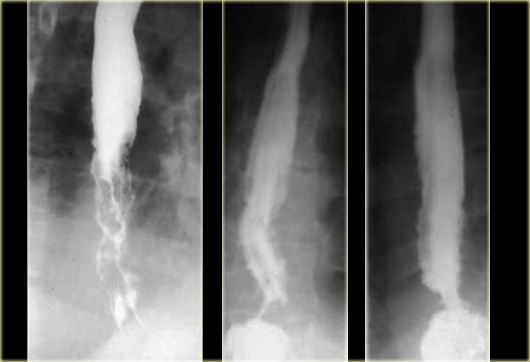

On the left three patients with esophageal narrowing as a result of metastatic mediastinal lymphnodes.

On the far left a bronchogenic carcinoma.

Extrinsic mediastinal lymph nodes produce long obtuse angles at the interface with esophagus.

In the middle another bronchogenic carcinoma.

Irregular distal esophageal wall due to invasion of esophagus.

In the right a patient with a breast carcinoma.

There is mediastinal lymphadenopathy with esophageal invasion and obstruction.

Due not confuse normal esophageal irregularities for impressions by lymphnodes.

On the left a normal esophagus.

The esophagus (arrow) protrudes under aortic arch into right side of AP window.

Next to it mediastinal nodes (arrows) that displace the esophagus to right in a patient with bronchogenic carcinoma.

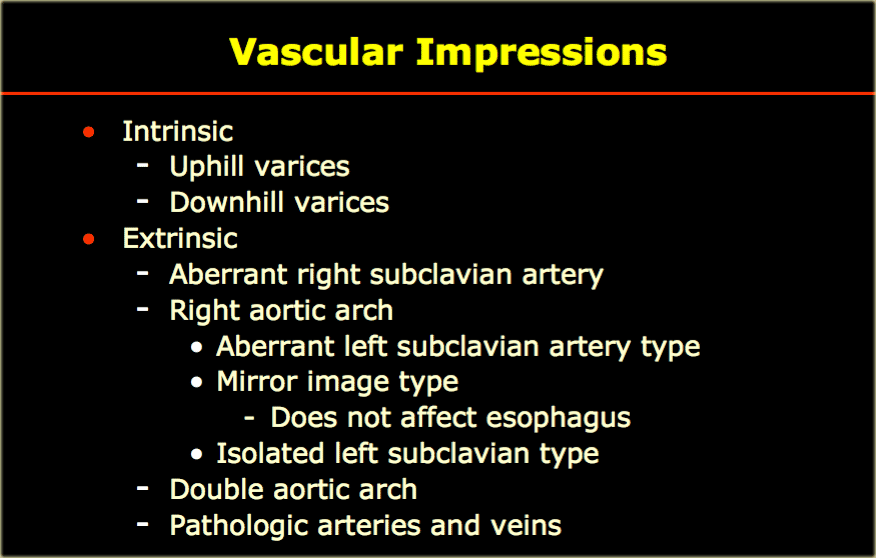

Vascular impressions

On the left a list of vascular structures that may cause impressions on the esophagus.

Uphill varices

With portal hypertension, elevated portal venous pressure leads to reversed (hepatofugal) flow bypassing the liver through the left gastric vein to dilated esophageal and periesophageal veins that anastamose with the azygos and hemiazygos veins which drain uphill into the superior vena cava.

Filling defects due to varices are characterized by change in appearance during the examination related to breath holding and thoracic pressure.

On the left are CT images of a patient with large Uphill varices secondary to cirrhosis with portal hypertension.

On the left CT images of a patient with uphill varices.

Uphill varices can be mass-like as seen in the case on the left.

Continue with next image.

The CT shows mass-like mediastinal and esophageal varices (arrows).

Varices have to be differentiated from varicoid carcinoma.

On the left the fixed appearance of filling defects indicates tumor rather than varices.

Note sharp upper margin of lesion (arrows)

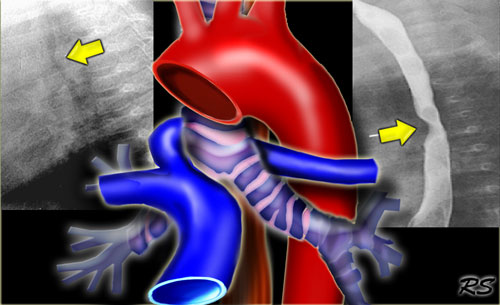

Downhill Varices

With superior vena caval obstruction, upper body venous blood flows caudally downhill through esophageal veins to the azygos vein which empties into the superior vena cava caudal to the obstruction.

If the obstruction is at or below the azygos, the blood flow extends further caudally to the portal system and then the hepatic veins to the inferior vena cava and the right atrium.

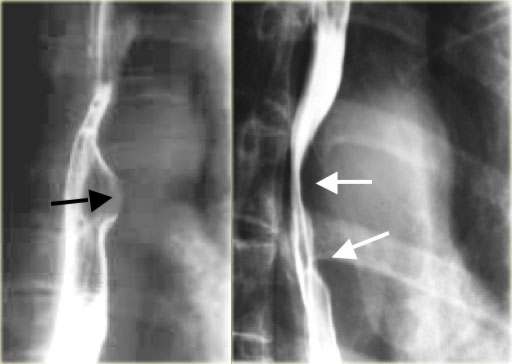

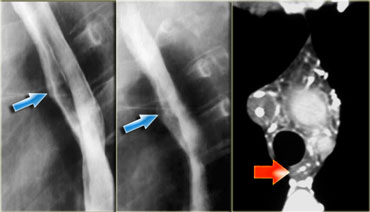

On the left downhill varices in a patient with a superior vena cava obstruction due to histoplasmosis.

On the barium study inconstant filling defects (arrows) represent downhill varices in upper esophagus.

The angiogram demonstrates collateral vessels including a dilated left superior intercostal vein (arrow).

The barium study demonstrates inconstant filling defects (blue arrows) due to downhill varices in upper esophagus.

CT demonstrates esophageal (red arrow) and mediastinal varices.

Continue with venogram.

Upper arm venograms show SVC obstruction.

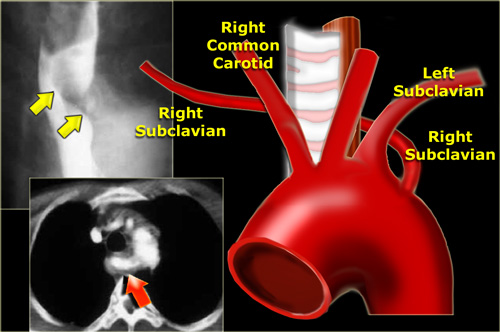

Aberrant right subclavian artery

This is the most common thoracic arterial anomaly and rarely causes symptoms.

The artery extends up and to the right producing a dorsal diagonal impression on the esophagus (arrows).

The CT demonstrates that the aberrant artery (arrow) is last vessel from arch and extends dorsal to trachea and esophagus.

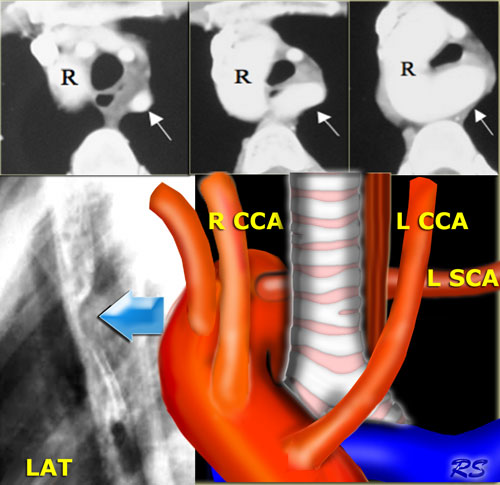

Right aortic arch with aberrant left subclavian artery

A right aortic arch with an aberrant left subclavian artery is most often an incidental finding.

A right aortic arch with mirror-image branching however is almost always associated with congenital heart disease.

CT shows right arch (R) and aberrant left subclavian artery (arrow) arising low off arch and extending to left dorsal to esophagus and trachea.

On the left the esophagram of a patient with a right arch that produces a dorsal indentation on this lateral view (blue arrow).

The diagram shows the aberrant left subclavian artery (L SCA) dorsal to the trachea and esophagus.

Double ArchLEFT: Right and left arch indent esophagus (arrows) at different levels RIGHT: Angiogram with double arch in asymptomatic 65-year-old

Double ArchLEFT: Right and left arch indent esophagus (arrows) at different levels RIGHT: Angiogram with double arch in asymptomatic 65-year-old

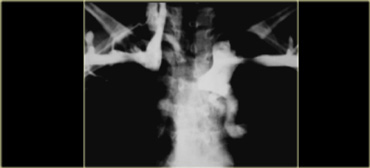

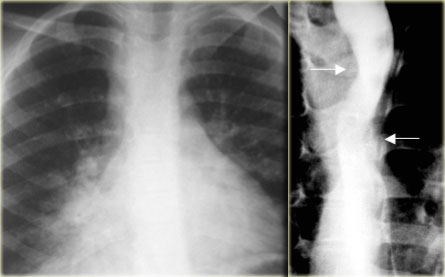

Double Arch

Double arch most often presents with airway obstruction, dysphagia, aspiration in children.

The arches indent esophagus at different levels.

On the left another double arch.

Chest radiograph with right lung consolidation due to aspiration in 6-year-old.

Right and left arch indent esophagus (arrows) at different levels

Aberrant left pulmonary artery: aberrant artery extends between trachea and esophagus indenting both (arrows)

Aberrant left pulmonary artery: aberrant artery extends between trachea and esophagus indenting both (arrows)

Aberrant left pulmonary artery

The aberrant left pulmonary artery indents the trachea dorsally and esophagus ventrally as it extends between them.

Narrowing of right bronchus can cause air trapping or atelectasis.

Tortuous aorta

A tortous descending aorta is a common cause of extrinsic impression on the esophagus.

The image on the far left shows a narrowed distal esophagus.

Oblique view shows esophageal indentation by aorta with obtuse margins (arrows) characteristic of extrinsic compression.

Aortic pathology

On the far left the normal aortic arch impression on the esophagus.

This impression can be enlarged if there is dilatation of the aorta as seen in this patient with a mycotic aortic arch aneurysm (arrows).

Coarctation

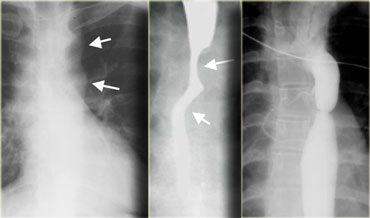

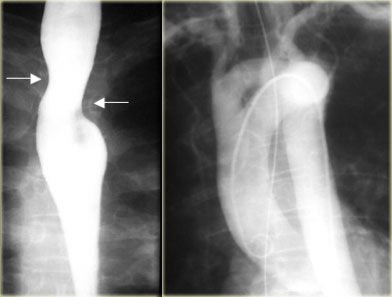

On the left 3 images of a patient with a coarctation.

On the chest film the 'Figure 3' shape of aortic knob due pre and post stenotic dilatation (arrows).

The barium study demonstrates the 'Reverse 3 figure' indention of esophagus by pre and post stenotic aortic dilatation (arrows).

An angiogram demonstrates a coarctation with pre and post stenotic dilatation in another patient.