Esophagus I: anatomy, rings, inflammation

Terrence C. Demos, MD, Harold V. Posniak, MD, Wayde Nagamine, MD and Mary Olson, MD

Department of Radiology of the Loyola University Medical Center, USA

Publicationdate

In Esophagus part I we will discuss:

- Basic anatomy and function.

- Rings, webs and diverticula.

- Hiatus hernia.

- Inflammation and infection.

- Strictures

- Acute esophageal syndromes.

- Benign and malignant neoplasms.

- Vascular impressions.

Anatomy and Function

LEFT: Lateral view: Epiglottis (red arrow). Post cricoid impression (yellow arrows). Cricopharyngeous impression (white arrow).RIGHT: AP-view: Small lateral pharyngeal pouches (arrows)

LEFT: Lateral view: Epiglottis (red arrow). Post cricoid impression (yellow arrows). Cricopharyngeous impression (white arrow).RIGHT: AP-view: Small lateral pharyngeal pouches (arrows)

Hypopharynx

Common structures that we can visualize are:

- Epiglottis

- Post cricoid impression: Submucosal venous plexus over cricoid cartilage produces inconstant indentation of the anterior esophageal wall.

- Lateral pharyngeal pouches:

Protrusion of lateral pharyngeal wall through thyrohyoid membrane at site of penetration by laryngeal vessel and nerve branches.

If a normal pouch becomes enlarged, it is termed a lateral pharyngeal diverticulum. - Cricopharyngeal muscle impression: Extrinsic impression on posterior esophagus by contracted muscle.

The esophageal wall is composed of:

-

Mucosa:

- Non-keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium

- Interdigitates with gastric columnar epithelium at or below diaphragm with the irregular boundary forming the Z line.

-

Musculature:

- Inner circular layer

-

Outer longitudinal layer:

- Upper 1/3 striated muscle

- Middle 1/3 striated and smooth muscle

- Lower 1/3 smooth muscle

- No serosa

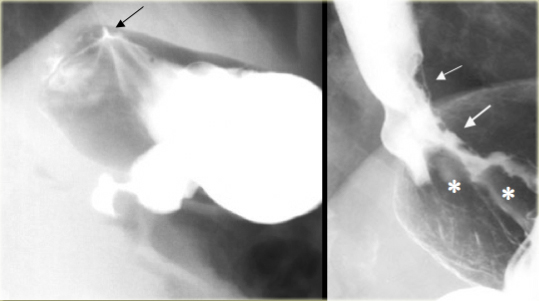

At the gastroesophageal junction smooth, uniform folds in gastric fundus converge on very distal esophagus (arrow).

Image next to it shows abnormal gastroesophageal junction: Barium outlines thick, irregular mucosal folds (asterisks).

Fundal adenocarcinoma invades esophagus (arrows)

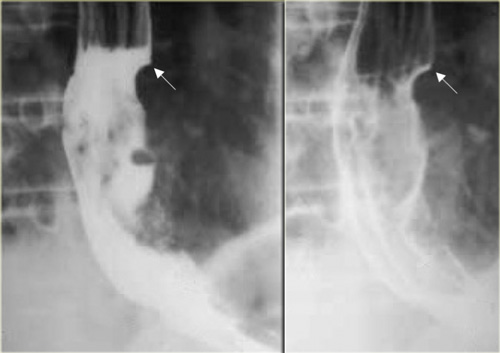

Cricopharyngeal achalasia in 46-year-old woman. Feeling of lump in throat. Persistent indentation (arrow) by cricopharyngeus muscle that does not relax as bolus progresses caudally

Cricopharyngeal achalasia in 46-year-old woman. Feeling of lump in throat. Persistent indentation (arrow) by cricopharyngeus muscle that does not relax as bolus progresses caudally

Upper esophageal sphincter

- Primarily formed by cricopharyngeal muscle.

- Located at the C5-C6 level

- Normally relaxes with bolus

- Abnormalities

- Delayed relaxation

- Early closure

- No relaxation: with or without symptoms; if symptomatic, termed cricopharyngeal achalasia

Lower esophageal sphincter

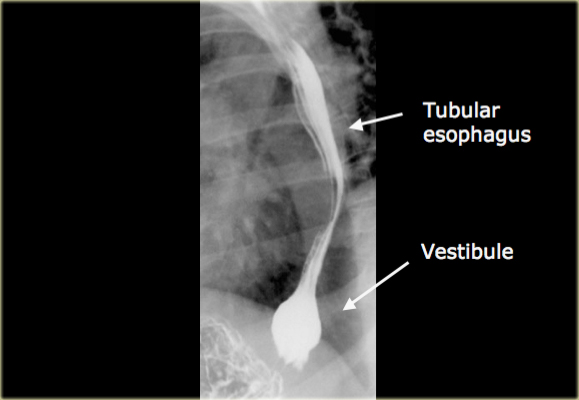

- Distal 2-4 cm esophageal high pressure zone defined by manometry. Corresponds to vestibule on esophagram.

- Prevents gastroesophageal reflux.

- Drugs and many types of food and drink affect lower esophageal sphincter and can lead to reflux.

- Glucagon relaxes the lower esophageal sphincter when used for air-contrast upper gastrointestinal examination.

- The tubular esophagus extends to just above the diaphragm.

- Bulbous distention of the distal esophagus is called the vestibule and corresponds to the manometrically-defined lower esophageal sphincter.

This distention is best demonstrated by breath holding in inspiration or a Valsalva maneuver.

Do not mistake this for a hiatal hernia.

Gastroesophageal reflux

Spontaneous gastroesophageal reflux has been demonstrated in up to 1/3 of patients with reflux esophagitis.

Various maneuvers during the examination have been used to increase sensitivity, but these are generally discredited as not being physiologic.

In addition many asymptomatic patients have spontaneous reflux so that reflux during an esophagram is not sensitive or specific for relating symptoms to reflux.

Esophageal peristalsis

Normal:

- Primary contraction: Propels bolus through the esophagus

- Secondary contraction: Follows primary contraction and propels any remaining bolus from thoracic esophagus

Abnormal:

- Tertiary contractions, presbyesophagus: Nonpropulsive contractions

- Diffuse esophageal spasm

- Nutcracker esophagus

- Decreased peristalsis resulting from achalasia, scleroderma, dermatomyositis, polymyositis, esophagitis, and secondary to many other diseases

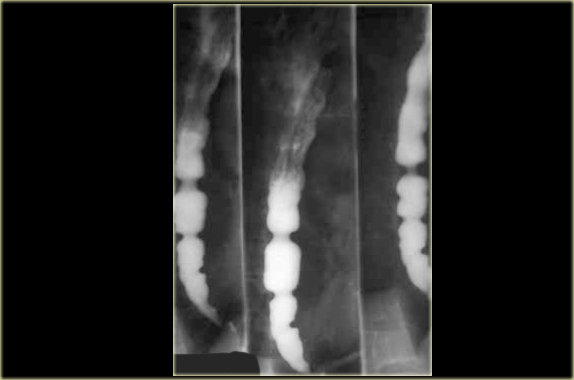

On the left tertiary contractions on first swallow (left).

Normal primary contraction on next swallow (right).

These tertiary contractions are non-propulsive, transient, and intermittent contractions that are inconstant in location and not accompanied by symptoms, usually in older patients.

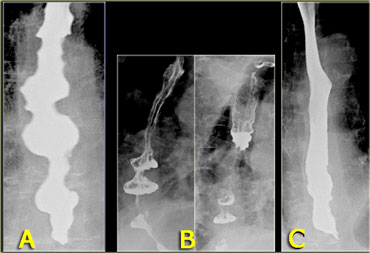

A. Initial nonpropulsive tertiary contractions B. Three images during examination show collections resembling diverticula C. Image later in examination shows resolution of tertiary contractions

A. Initial nonpropulsive tertiary contractions B. Three images during examination show collections resembling diverticula C. Image later in examination shows resolution of tertiary contractions

Sometimes transient tertiary contractions may simulate diverticula.

On the left images of a patient with tertiary contractions, that during the examination look like diverticula.

Diffuse esophageal spasm

Diffuse esophageal spasm produces intermittent contractions of the mid and distal esophageal smooth muscle, associated with chest symptoms.

Manometry shows simultaneous nonpropulsive contractions on at least 10% of swallows.

Diagnosis is based on imaging, manometry, and symptoms.

Nutcracker esophagus

Nutcracker esophagus is a non-cardiac cause of chest pain attributed to high amplitude distal esophageal peristalsis.

This is a controversial diagnosis that is made by manometry and does not have imaging manifestations

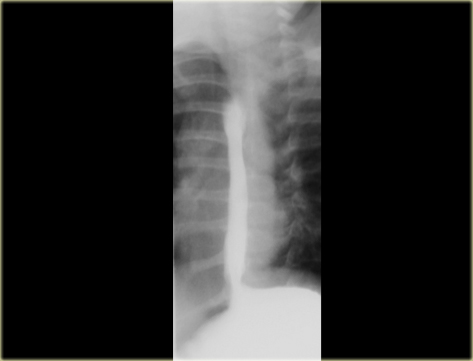

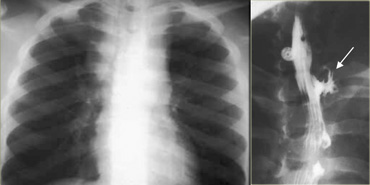

LEFT: Dilated esophagus (arrows) appears as long, well-defined structure paralleling heart RIGHT: Dilated esophagus usually deviates to right. Narrowing (arrow) at hiatus.

LEFT: Dilated esophagus (arrows) appears as long, well-defined structure paralleling heart RIGHT: Dilated esophagus usually deviates to right. Narrowing (arrow) at hiatus.

Achalasia

- Presentation:

- Equal M:F incidence, most common in middle-age

- Slow progression of dysphagia

- Increased incidence of carcinoma

-

Etiology:

- Unknown, although esophageal ganglion cells are decreased

- Incomplete or absent relaxation of LES with swallowing

- Absent primary peristaltic waves

-

Esophagram:

- Dilation with absent peristalsis

- Smooth tapering at esophageal hiatus

- Distal carcinoma may simulate achalasia (pseudoachalasia)

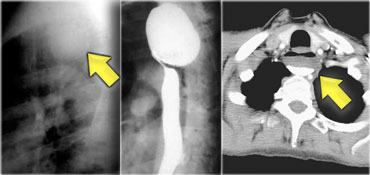

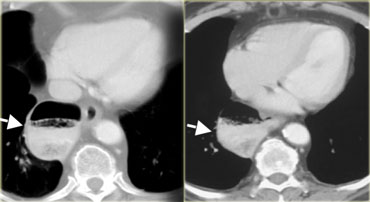

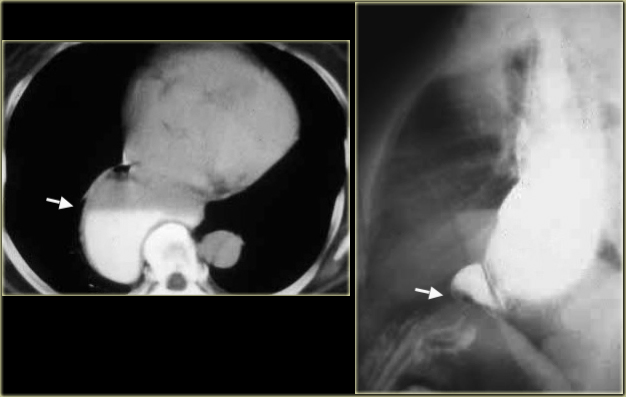

LEFT: CT shows dilated esophagus (arrow) that led to esophagram.RIGHT: Esophagram shows narrowing (arrow) at level of hiatus.

LEFT: CT shows dilated esophagus (arrow) that led to esophagram.RIGHT: Esophagram shows narrowing (arrow) at level of hiatus.

On the left another patient with achalasia.

LEFT: Dilated esophagus (arrows) is projected behind right atrium.MIDDLE and RIGHT: Smooth, tapered narrowing just above diaphragm (arrows).

LEFT: Dilated esophagus (arrows) is projected behind right atrium.MIDDLE and RIGHT: Smooth, tapered narrowing just above diaphragm (arrows).

On the left another patient with achalasia.

During fluoroscopy some peristalsis was seen with typical smooth, tapered narrowing just above diaphragm (arrows).

Lower esophageal rings

- A-Ring

- Muscular contraction at the junction of tubular and vestibular esophagus

- No definite anatomic correlate

-

Mucosal ring at anatomic squamocolumnar junction (Z-line)

- Best or only seen with vestibular distension

- Normally

- May cause episodic dysphagia if esophagus is narrowed, then termed a Schatzki ring

- > 20 mm wide, no obstruction

- 13-20 mm wide, may obstruct

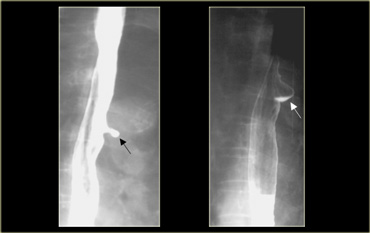

On the left a patient with a ring due to muscular contraction. Notice incidental gastric diverticulum (asterisk).

On the left another patient with a non-persistent ring at the apex of a sliding hiatus hernia.

The esophageal B-ring is located at the squamocolumnar junction, also termed the 'Z' line.

The appearance does not change during the examination.

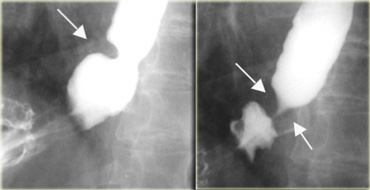

On the left a patient with a 'B' ring (arrows) several cm above diaphragm at the apex of sliding hiatus hernia.

Note unchanged appearance on these two images.

On the left a 52-year-old man with episodic dysphagia.

The image on the far left does not show a abnormality, but distal esophagus not distended .

With dilation of the distal esophagus, a 13 mm wide Schatzki B-ring (arrows) that caused intermittent obstruction is demonstrated at the apex of a hiatus hernia (arrowhead).

On the left a 71-year-old man with chest pain after fast food lunch.

Distal obstructing filling defect (arrow) is a piece of meat that passed into stomach during study.

Follow-up esophagram shows Schatzki B-ring (arrows) that caused obstruction.

Webs and Diverticula

Esophageal web

- 10% incidence at autopsy

- Can be congenital or acquired

- Most in hypopharynx and proximal esophagus

- Majority protrude from anterior esophageal wall

- Symptoms if lumen > 50% compromised

- Sideropenic dysphagia (Plummer-Vinson syndrome)

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Esophageal web with dysphagia

- Increased incidence of carcinoma

- Validity of syndrome debatable

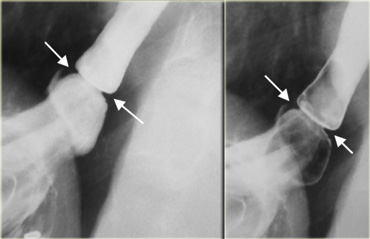

On the left images of an asymptomatic 52-year-old man.

AP and Lateral views show short, thin web (arrows) with minimal intraluminal extension.

On the left images of a 42-year-old woman with dysphagia due to web.

There is > 50% luminal narrowing

Diverticula

Pulsion diverticula are due to increased intraluminal pressure. There are many pulsion diverticula:

- Zenker's

- Killian-Jamieson

- Epiphrenic

- Midesophagus

- Aortopulmonary recess

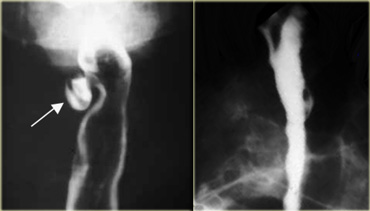

On the left a patient with a Zenker's diverticulum as a result of premature closure of the cricopharyngeal muscle.

Traction diverticula are secondary to adjacent disease.

Most located in mid-esophagus.

Zenker's diverticulum

A Zenker's diverticulum is a pulsion hypopharyngeal false diverticulum with only

mucosa and submucosa protruding through triangular posterior wall weak

site (Killian's dehiscence) between horizontal and oblique components

of cricopharyngeus muscle.

The etiology is controversial and is probably due to elevated upper esophageal

pressure, cricopharyngeus dysfunction and reflux.

The clinical presentation can be dysphagia, regurgitation, aspiration

or a mass or air-fluid level on neck or chest radiographs.

The esophagram shows collection with midline posterior origin just above

cricopharyngeus protruding lateral, usually to left, and caudal with

enlargement.

Killian-Jamieson diverticulum is a pulsion diverticulum, that protrudes through a lateral anatomic weak site of the cervical esophagus below the cricopharyngeus muscle, unlike the posterior, midline origin of a Zenker's diverticulum.

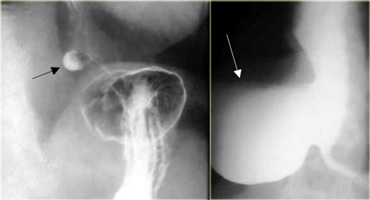

AP view shows diverticulum (arrow) originating laterally.

Lateral view confirms diverticulum does not originate posteriorly as a Zenkers diverticulum would.

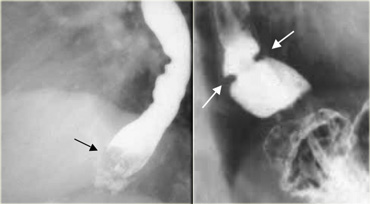

LEFT: Small diverticulum (arrow) in asymptomatic patient RIGHT: Large diverticulum (arrow) in patient with aspiration

LEFT: Small diverticulum (arrow) in asymptomatic patient RIGHT: Large diverticulum (arrow) in patient with aspiration

Epiphrenic diverticulum

These pulsion diverticula are classified by their location near the diaphragm. /ul>

If large they can narrow the esophagus or lead to aspiration.

On the left another example of an epiphrenic diverticulum.

The CT demonstrates a large diverticulum (arrow) extends to the right just above diaphragm.

This patient was asymptomatic

Aortopulmonary window diverticulum

The normal esophagus transiently protrudes into the aortopulmonary window.

Fixed protrusion is an inconsequential diverticulum.

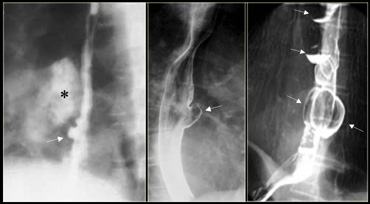

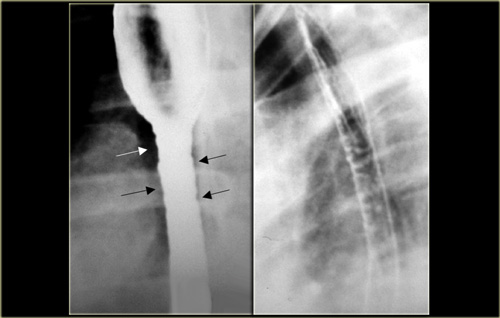

On the left small aortopulmonary diverticula (arrows), that are incidental findings in two patients.

On the far left a traction diverticulum (arrow) due to hilar granulomatous disease.

Calcified adenopathy (asterisk).

In the middle a pulsion diverticulum (arrow) due to high intraluminal pressure.

On the right multiple pulsion diverticula (arrows) that preceded Heller myotomy for achalasia.

On the left a traction diverticulum (arrows) secondary to post primary TB.

It simulates a cavitary lung lesion on the chest radiograph.

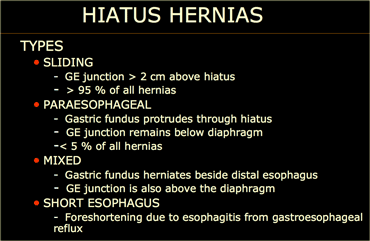

Pseudodiverticula can be seen in reflux esophagitis. On the left a patient with a hiatus hernia, reflux esophagitis, and pseudodiverticula (arrows) at site of proximal stricture

Left: Iatrogenic perforation (arrow). MIDDLE: Communicating esophageal duplication (arrows). RIGHT: Extravasation from iatrogenic perforation of hypopharynx in neonate

Left: Iatrogenic perforation (arrow). MIDDLE: Communicating esophageal duplication (arrows). RIGHT: Extravasation from iatrogenic perforation of hypopharynx in neonate

Other pathologic conditions can simulate diverticula. On the left two patients with a iatrogenic perforation and a patient with a communicating duplication cyst.

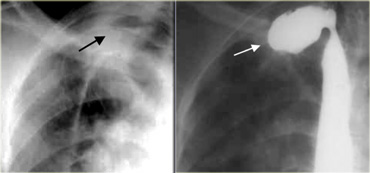

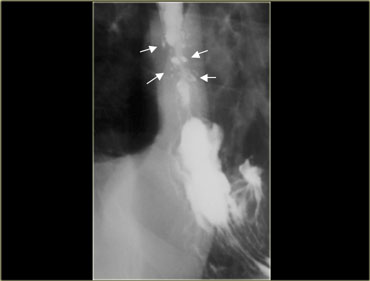

Hiatus hernia

The types of hiatus hernia are listed in the table on the left.

The relationship between hiatus hernia, reflux and reflux esophagitis is controversial and poorly understood.

Most patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) have hernias.

Many patients with hiatus hernias do not have reflux.

Many patients with reflux do not have hiatus hernias.

Presence of reflux correlates poorly with GERD.

A sliding hiatus hernia is of doubtful significance when an isolated finding in the absence of clinical or imaging findings of esophagitis.

Diagnosis of GERD is based on imaging or endoscopic findings of esophagitis, not presence of a hiatus hernia.

Sliding hernia

On the left initially, GE junction is below the esophageal hiatus.

Later, stomach protrudes through hiatus.

Neither the hernia or stricture (arrow) due to reflux esophagitis were visible early in the examination.

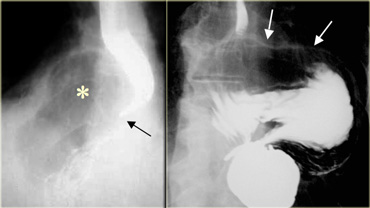

Paraesophageal hernia

Large hernias can cause symptoms, and with progressive hiatal widening, increasing protrusion and rotation of the stomach can lead to gastric volvulus that can be complicated by hemorrhage, obstruction, strangulation, perforation.

On the left two examples.

On the far left gas filled gastric fundus (asterisk) protrudes through hiatus but GE junction (arrow) is below diaphragm.

Next to it a paraesophageal hernia with most of 'upside down' stomach in chest with greater curvature (arrows) flipped up.

On the left a mixed hernia.

Distal esophagus is adjacent to the herniated gastric fundus, but unlike a paraesophageal hernia, the gastroesophageal junction (arrow) is above rather than below the diaphragm.

Inflammation and Infection

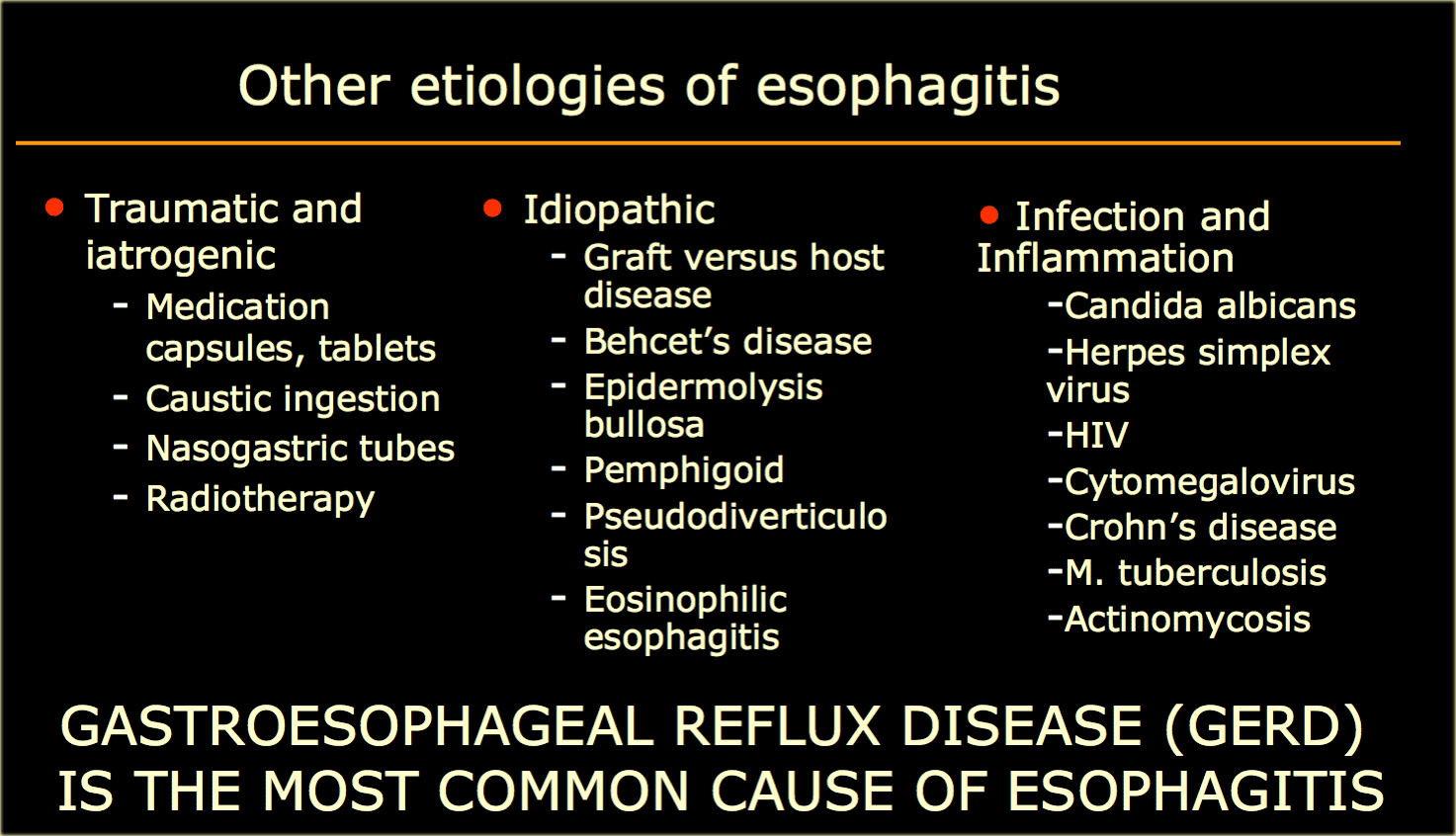

Gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) is the most common cause of esophagitis.

Other causes of esophagitis are listed in the table on the left.

Reflux esophagitis

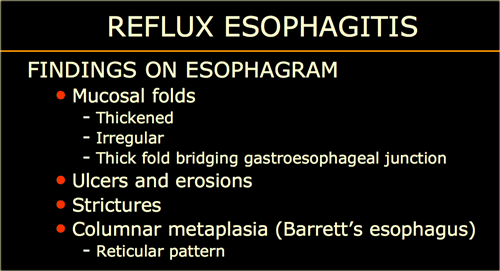

The findings on barium studies are listed in the table on the left.

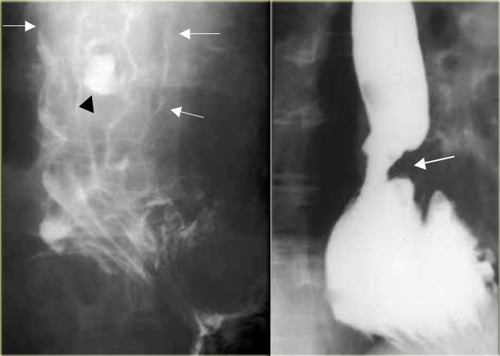

Air-contrast esophagram shows thick esophageal mucosal folds (arrows) and an ulcer (arrowhead) due to GERD.

Single contrast esophagram shows stricture (arrow) and sliding hiatus hernia

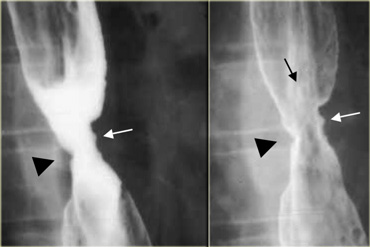

On the left Irregular stricture (arrowhead) and erosions (arrows) due to GERD.

Barrett's esophagus

Barrett's esophagus (columnar metaplasia) is the result of long-standing reflux esophagitis.

Most patients have reflux and a hiatus hernia.

The diagnosis is strongly suggested by:

- Mid or high esophageal ulcer

- Mid or high esophageal web-like stricture

- Reticular mucosal pattern

On the left a patient with a Barrett's esophagus. The reticular mucosa is characteristic of Barrett's columnar metaplasia, especially with the associated web-like (arrow) stricture.

On the left a patient with a Barrett's esophagus with an adenocarcinoma.

There are abnormal distal mucosal folds.

The upper margin of adenocarcinoma makes right angle with esophageal wall (arrow) indicating a mural lesion in patient with GERD and Barrett's esophagus.

Infectious esophagitis

Candida esophagitis

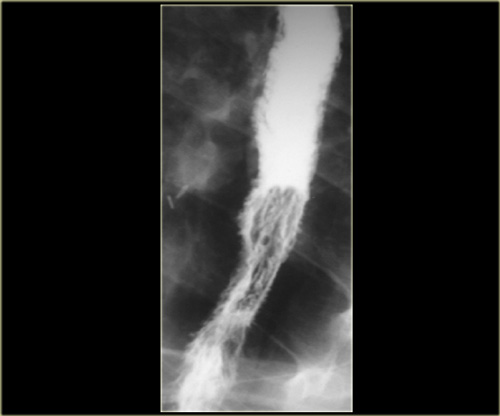

On the left a patient with an infectious esophagitis due to candida.

The barium stury shows numerous fine erosions and small plaques due to Candida albicans in immunocompromised patient.

Cytomegalovirus esophagitis

On the left an AIDS patient with an infectious esophagitis due to Cytomegalovirus.

Such giant ulcers can also be due to HIV alone.

Crohn's esophagitis

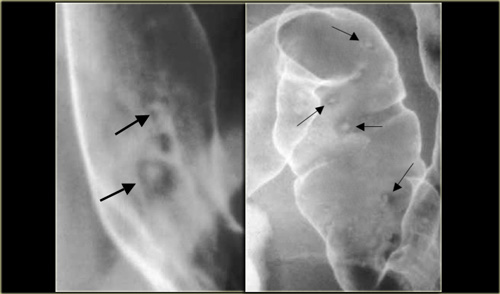

On the left a patient with Crohn's disease.

There is a granulomatous esophagitis with aphthous ulcers (arrows).

This is an uncommon manifestation of Crohn's disease.

The figure on ther right shows the more common colonic aphthous ulcers.

TB esophagitis

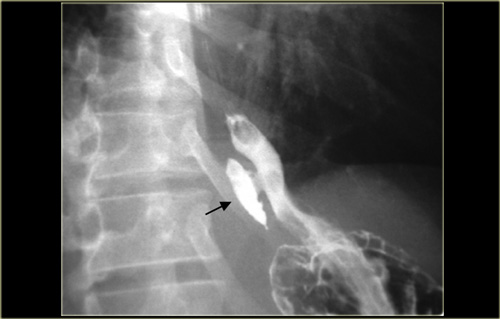

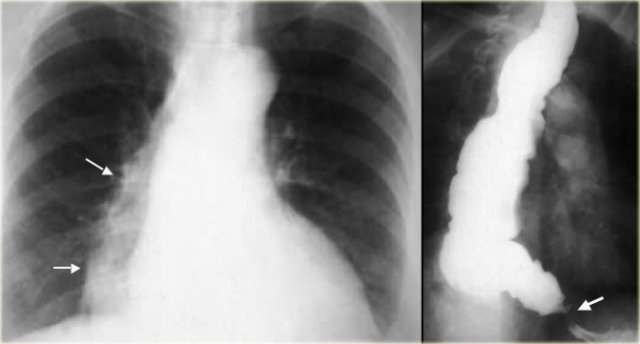

On the left a patient with an infectious esophagitis due to primary TB.

There is an irregular sinus tract from proximal esophagus (arrow).

Chest radiograph shows enlarged lymph nodes widening mediastinum due to primary tuberculosis.

Pseudodiverticulosis

Dilated mural glands or pseudodiverticulosis, is usually associated with histologic or endoscopic signs of inflammation, and many patients have strictures due to GERD.

On the left a patient with esophageal pseudodiverticulosis.

Eosinophilic esophagitis

This diagnosis may be suggested by peripheral eosinophilia and confirmed by > 20 eosinophils per HPF on biopsy.

Patients often have dysphagia and allergies.

Imaging finding include diffuse narrowing, strictures, and a ringed appearance similar to transverse (feline esophagus) folds that are transient or associated with reflux.

Steroid therapy is often curative.

On the left a patient with eosinophilic esophagitis.

There is diffuse distal narrowing and corrugated margins (arrows) due to ring-like indentations, that are characteristic of eosinophilic esophagitis.

Glycogen acanthosis

Glycogen plaques are frequently seen at endoscopy.

The reported

incidence at endoscopy is 5 to 15% of all patients.

These benign epithelial collections of glycogen produce small mucosal nodules.

Nodules are smooth and well-defined.

This may be a degenerative process and produces no symptoms.

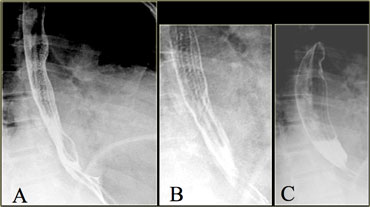

Feline esophagus: A, B: Show fine horizontal esophageal folds; C: Later image during study no longer shows folds

Feline esophagus: A, B: Show fine horizontal esophageal folds; C: Later image during study no longer shows folds

Feline esophagus

The delicate, concentric and transiently appearing folds of a feline esophagus should be distinguished from the thicker, interrupted, fixed folds indicative of longitudinal scarring from reflux esophagitis.

The characteristics of a feline esophagus are:

- Horizontal striations due to muscularis mucosa contractions

- Normal in cats

- Most often transient and insignificant

- May be associated with gastroesophageal reflux or esophagitis