Cystic Lung Cancer

Onno Mets and Robin Smithuis

Amsterdam University Medical Center, Vancouver General Hospital and Alrijne hospital Leiderdorp

Publicationdate

Cystic primary lung cancer is increasingly being recognized as a unique imaging morphology.

In this article we will discuss the imaging features and management

Press ctrl+ for larger images and text on a PC or ⌘+ on a Mac.

Most images can be enlarged separately by clicking on them.

Introduction

Cystic primary lung cancer is often missed or misinterpreted, which is most likely due to their unique imaging appearance, showing overlap with benign entities such as infection.

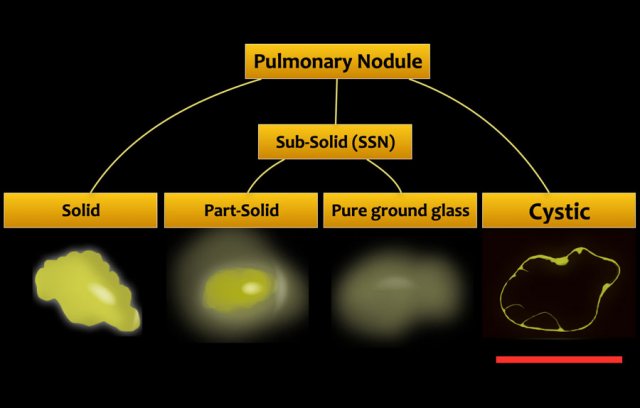

The appearance is different from solid and subsolid nodules, which are the more commonly known CT appearances of lung cancer (fig).

Terminology

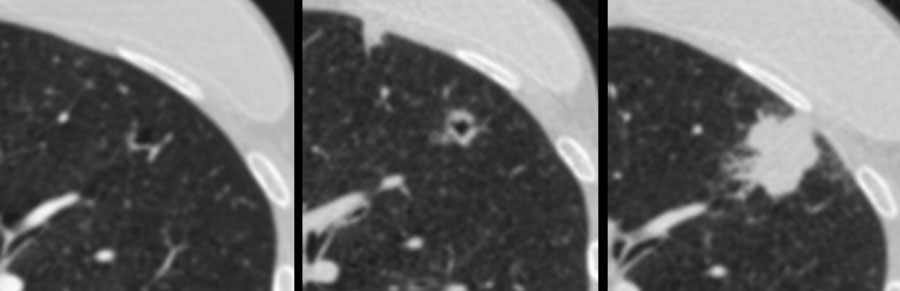

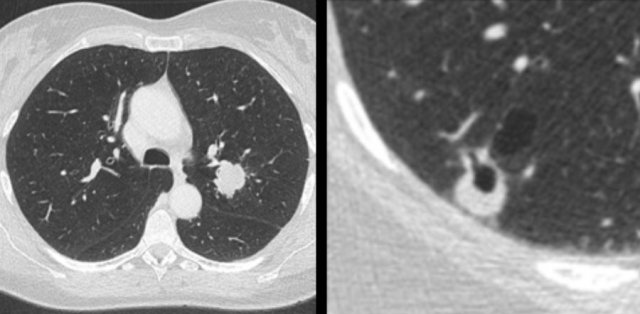

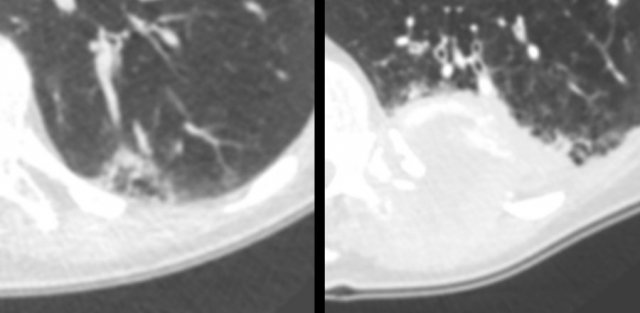

Examples of cystic lung cancer with an exophytic (left panel) and endophytic (right panel) solid component.

Examples of cystic lung cancer with an exophytic (left panel) and endophytic (right panel) solid component.

A cystic pulmonary nodule may be defined as solid and/or ground glass attenuation in relation to a well-defined parenchymal air space.

A cystic nodule may demonstrate:

- Exophytic or endophytic solid component adjacent to the cystic air space (fig).

- Irregular partial or circumferential wall thickening.

- Complex appearance with subsolid components and multilocular air spaces.

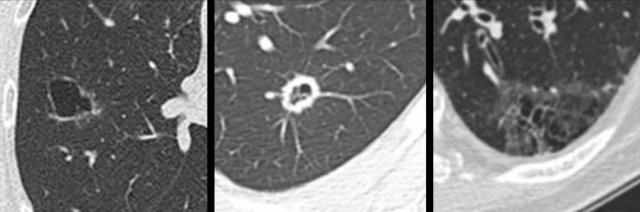

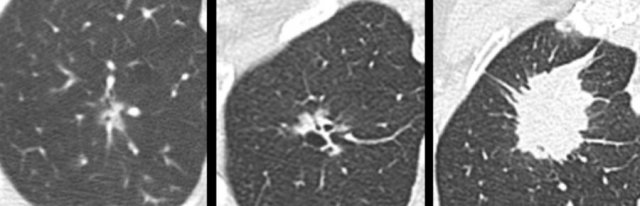

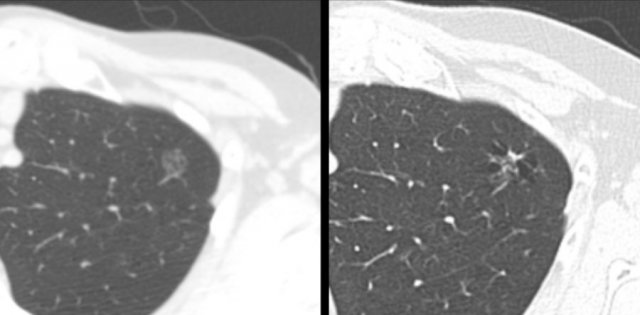

The images show more examples of cystic lung cancer with a thin (left panel) and thick (middle panel) irregular wall thickening, and a more complex appearance with extensive ground glass and multilocular air spaces (right panel).

Several classification systems have been proposed based on this imaging morphology [1,2].

Clinical implications of any subclassification are yet unknown and therefore they are of limited value for routine radiology care.

Solidification

Solidification is the opposite of cavitation.

Solidification is a process that is often demonstrated by cystic lung cancers – where the solid tissue component increases over time and may eventually even obliterate previous ground glass and/or cystic air spaces completely, leading to a solid mass.

Here another example of a cystic lung cancer demonstrating ‘solidification’ from a baseline precursor lesion with subtle irregular wall thickening into a solid mass at time of diagnosis.

It is important to note that cavitation – which is the process of central lucency formation due to expulsion of necrotic tumour content – can only be assessed on serial CT.

Although very often encountered in reports of single time point CT, this term should be applied with caution.

It may insinuate a differential diagnosis of infection or other disease that steers away from the correct diagnosis of a primary lung cancer that is most likely an adenocarcinoma [3,4].

The images show another example of a cystic lung cancer demonstrating ‘solidification’.

Daily practice

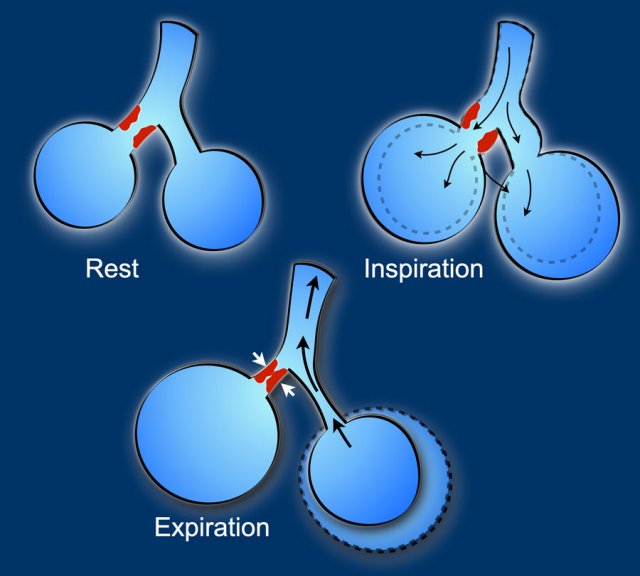

Patient with a T1c adenocarcinoma in the left upper lobe (left panel). Growing synchronous cystic lesion in the right lower lobe (right panel) that represented an unrelated second primary adenocarcinoma on histopathology. In daily practice

Patient with a T1c adenocarcinoma in the left upper lobe (left panel). Growing synchronous cystic lesion in the right lower lobe (right panel) that represented an unrelated second primary adenocarcinoma on histopathology. In daily practice

The prevalence of cystic lung cancer is not well established and ranges between 0.5% and 12%, depending on study population selection [1,5,6].

Presumably, cystic lung cancer morphology is not uncommon at all [4].

Several recognized associations are of specific importance to radiologists during daily CT reporting, as increased awareness and active search should be demonstrated in this population.

First, it has been recognized that cystic lung cancer regularly represents a secondary primary malignancy, either metachronous or synchronous with the first lung cancer (figure).

Second, a high percentage of patients with cystic lung cancer are (ex-)smokers and have pre-existent emphysema, although cystic lung cancers undeniably do occur in otherwise normal lungs.

Third, cystic lung cancers tend to occur in the periphery of the lung, which makes it a relevant entity to all radiologists who image part of the lungs, specifically neuro, abdominal and ER radiologists.

These images are of a patient with a left lower lobe cystic squamous cell carcinoma (left panel), who developed a right lower lobe cystic lesion (right panel) and subcarinal lymphadenopathy 3 years into follow-up.

Although initially considered contralateral metastatic disease, recommended tissue analysis showed an unrelated second primary squamous cell carcinoma on histopathology.

Histopathology

Cystic lung cancers are predominantly adenocarcinomas in about 80% of cases, with squamous cell carcinomas as the second most common subtype.

A rare number of other tumour types like adenosquamous, neuroendocrine and lymphoma have been reported.

Multiple underlying histopathologic substrates (eg. focal tumour proliferation, fibrosis, lepidic tumour growth along alveolar walls, emphysema) relate to the imaging features of cystic lung cancer and are responsible for either the solid component, septations, ground glass, and cystic air spaces [1,5,7].

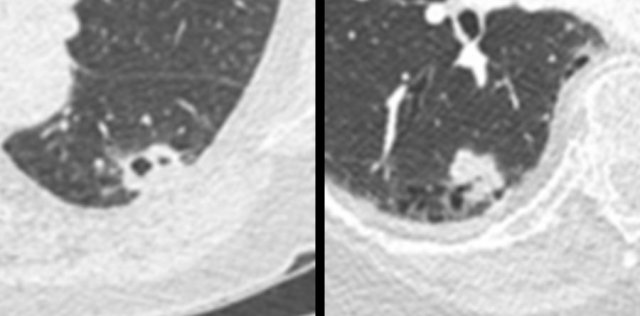

The most widely quoted mechanism of air space formation is “check-valve” ventilation.

The air can enter in inspiration but cannot return during expiration due to partial obstruction of the terminal airway proximal to the cystic air space due to tumour cells and fibrosis.

This leads to development, persistency and enlargement of the cystic air space.

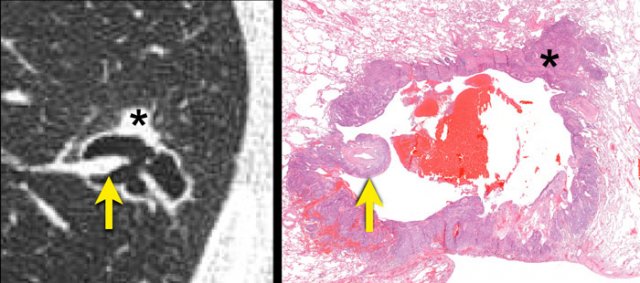

Radiologic-histopathologic correlation of a squamous cell carcinoma.

A cystic air space lined is by tumour cells (asterisk) most likely represents a dilated distal airway.

Check-valve ventilation due to more proximal airway narrowing by malignant cells and/or fibrosis is presumed.

A juxtaposed pulmonary artery with surrounding malignant cells projects into the lumen (arrow).

Natural history

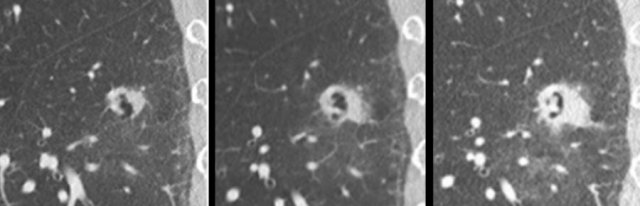

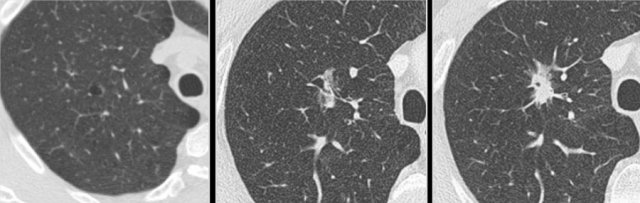

Example showing transition from pure ground glass (left panel) to cystic lung cancer morphology (right panel).

Example showing transition from pure ground glass (left panel) to cystic lung cancer morphology (right panel).

Cystic lung cancers are progressive lesions, inherent to their malignant aetiology.

Although they may be aggressive, many are rather slow-growing adenocarcinomas.

CT morphology may remain cystic over time, however, when the independent contribution of the underlying histopathologic substrates changes, lesion morphology may change over time.

Example showing transition from cystic (left and middle panel) to part-solid lung cancer morphology (right panel).

Example showing transition from cystic (left and middle panel) to part-solid lung cancer morphology (right panel).

Cystic nodules will either show increase of solid components, develop additional ground glass and cystic components and demonstrate increase in total lesion size.

It has retrospectively been shown that cystic lung cancers can both develop from small subsolid precursor lesions, as well as change from cystic precursor lesions into solid or subsolid cancers at time of diagnosis.

Lung cancer morphology is thus fluent and cystic components may be temporary.

This example shows transition from part-solid (left panel), to temporarily cystic (middle panel), to solid lung cancer morphology (right panel).

Mimickers

There are multiple benign diseases that may look like cystic primary lung cancer, including [3,4,8]:

- Infection (bacterial, granulomatous and fungal)

- Vasculitis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Amyloid

- Metastases, etc.

Previous imaging (including non-chest imaging), clinical information and lab values, as well as past medical history are often helpful to differentiate a suspected primary lung cancer from other aetiology.

In the absence of an overt underlying benign cause, any new lung cyst or cystic air space with associated subsolid component should raise the suspicion for a primary lung malignancy and managed accordingly with CT surveillance or biopsy, if appropriate.

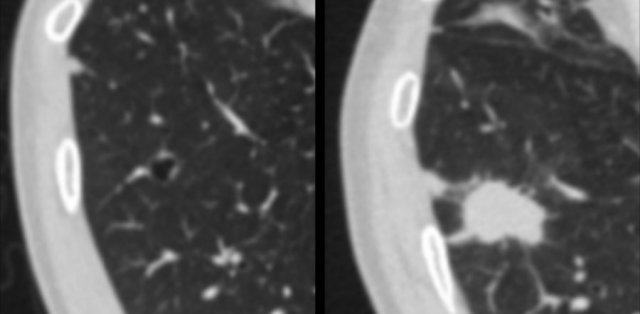

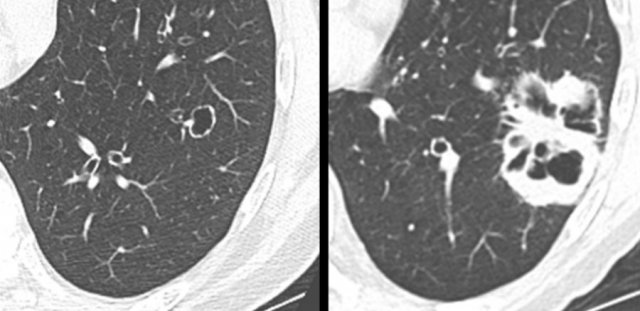

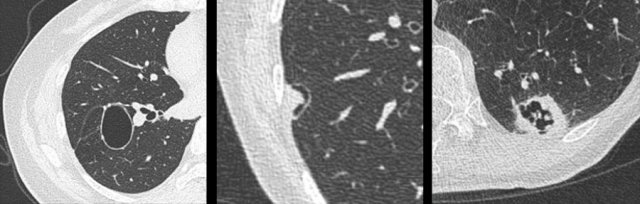

Mimickers of cystic lung cancer: Persistent loculated air space - left panel, rheumatoid nodule - middle panel and a scar - right panel.

Mimickers of cystic lung cancer: Persistent loculated air space - left panel, rheumatoid nodule - middle panel and a scar - right panel.

The images are examples of mimickers of cystic lung cancer morphology.

- A persistent loculated air space after spontaneous pneumothorax and subsequent wedge resection (left panel)

- Rheumatoid nodule in a patient with pulmonary and pleural RA involvement (middle panel)

- Incidental lung lesion that represented chronic changes and scar without signs of active infection or malignancy (right panel)

Absolute malignancy risk of solitary cystic nodules is currently unknown, as that would require prospective surveillance of all benign and malignant cystic nodules in a given cohort.

Nodule management

Multiloculated cystic lesion (left panel) interpreted as “non-specific”, despite a 6-month follow-up CT (for another reason) showed mild increase of ground glass, cystic air spaces and overall lesion size. The next CT was obtained for chest pain 2 years later, showing a large mass invading the chest wall (right panel). Patient died from metastatic lung adenocarcinoma.

Multiloculated cystic lesion (left panel) interpreted as “non-specific”, despite a 6-month follow-up CT (for another reason) showed mild increase of ground glass, cystic air spaces and overall lesion size. The next CT was obtained for chest pain 2 years later, showing a large mass invading the chest wall (right panel). Patient died from metastatic lung adenocarcinoma.

The currently available screening (Lung-RADS) or clinical (BTS and Fleischner) nodule management guidelines do not include cystic lung nodules.

Although no uniform guidance is provided and optimal surveillance strategy is unknown, it is crucial that these lesions are not lost to follow-up in order to prevent diagnostic delay and associated patient burden.

Pending potential incorporation into future guideline versions, the following strategy might be reasonable when a suspicious cystic nodule is encountered:

- Exclude rapid growth on a 3-month follow-up CT

- Continue surveillance with serial annual chest CT for 5 years, similar to part-solid nodule surveillance.

- Consider biannual follow-up if there is stability and only a tiny or no measurable solid component at all, similar to pure ground glass nodule surveillance.

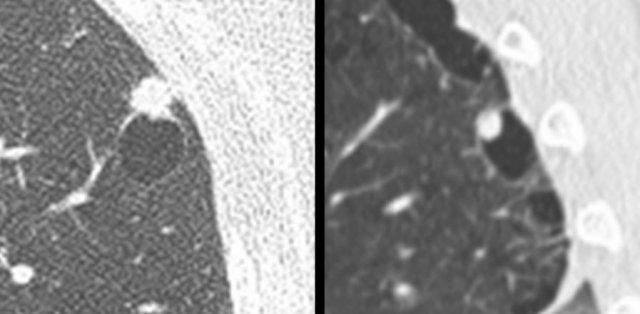

The images show a small cystic precursor lesion (left panel) initially interpreted as “thin-walled cavity, likely infection”.

The next CT was obtained for cough 4 years later, showing a T4 squamous cell carcinoma (right panel).

Patient was alive 2 years after resection and systemic treatment.

Staging

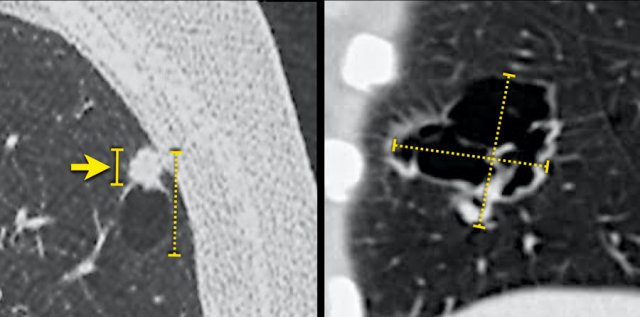

Possible overestimation of tumour burden due to inclusion of the cystic air space component in the total lesion size, when measured according to TNM 8th edition (stippled lines). The solid line (left panel) may better represent the invasive tumour component and associated prognosis.

Possible overestimation of tumour burden due to inclusion of the cystic air space component in the total lesion size, when measured according to TNM 8th edition (stippled lines). The solid line (left panel) may better represent the invasive tumour component and associated prognosis.

Despite the unique morphology of cystic lung cancer, staging is performed according to the ‘standard’ TNM 8th edition, which stages patient groups based on their prognosis.

However, measuring complex cystic lesions on CT may be prone to variability and one may posit that total lesion size (including the sometimes large cystic component) overestimates the total tumour burden, as it is more likely that the invasive solid component relates to the prognosis.

Future consideration of an adjusted classification might be reasonable, as is available for subsolid pulmonary malignancies [9].