Anatomy of Peritoneum and Mesentery

Angela D. Levy MD

Chief Gastrointestinal Radiology, Department of Radiologic Pathology, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington DC Associate Professor of Radiology, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD

Publicationdate

This review is based on a presentation given by Angela Levy and adapted for the Radiology Assistant by Robin Smithuis.

We will discuss the normal anatomy and physiology of the peritoneum and peritoneal cavity.

In part II we will discuss peritoneal tumors.

The illustrations are by Heike Blum

Images can be enlarged by clicking on them.

by Angela Levy

Definitions and Anatomy

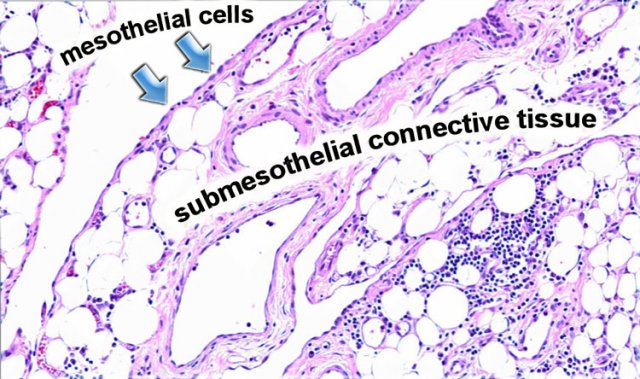

Peritoneum

The peritoneum is a serosal membrane, which is composed of a single layer of flat mesothelial cells supported by submesothelial connective tissue.

In this subserosal tissue there are fat cells, lymphatics, blood vessels and inflammatory cells like lymphocytes and plasma cells.

Mesenteries

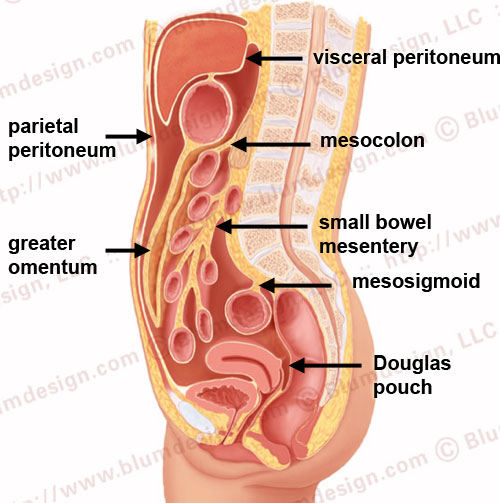

The visceral peritoneum lines all the organs that are intraperitoneal.

The parietal peritoneum lines the anterior, lateral and posterior walls of the peritoneal cavity.

The deepest portion of the peritoneal cavity is the pouch of Douglas in women and the retrovesical space in men, both in the upright and supine position.

The mesentery is a double fold of the peritoneum.

True mesenteries all connect to the posterior peritoneal wall.

These are:

- The small bowel mesentery

- The transverse mesocolon

- The sigmoid mesentery (or mesosigmoid)

Specialized mesenteries do not connect to the posterior peritoneal wall.

These are:

- The greater omentum: connects the stomach to the colon

- The lesser omentum: connects the stomach to the liver

- The mesoappendix: connects the apendix to the ileum

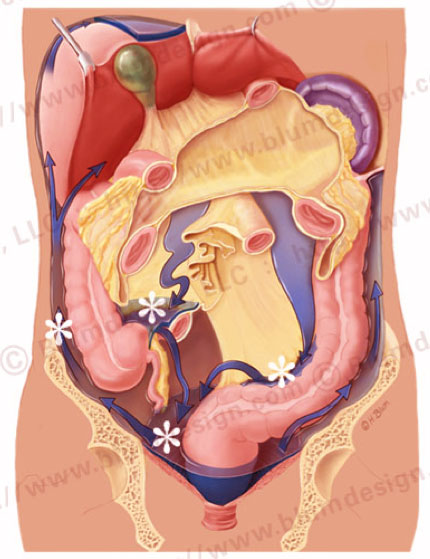

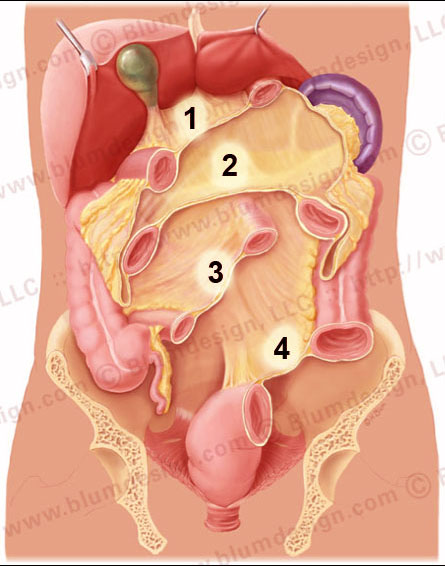

The lesser omentum (1), transverse mesocolon (2), small bowel mesentery (3) and the sigmoid mesentery (4)

The lesser omentum (1), transverse mesocolon (2), small bowel mesentery (3) and the sigmoid mesentery (4)

If you remove all of the intraperitoneal bowel, you get a good look at the cut-surface of the mesenteries:

- The lesser omentum

- Transverse mesocolon

- Small bowel mesentery

- Sigmoid mesentery

Notice that the small bowel mesentery has an oblique orientatien from the ligament of Treitz in the left upper quadrant to the ileocecal junction in the right lower quadrant.

Peritoneal circulation

These compartments enable the peritoneal cavity to have a normal circulation for peritoneal fluid.

In the normal abdomen without intraperitoneal disease, there is a small amount of peritoneal fluid that continuously circulates.

The movement of fluid in this circulatory pathway is produced by the movement of the diaphram and peristalsis of bowel.

It predominantly flows up the right paracolic gutter which is deeper and wider than the left and is partially cleared by the subphrenic lymphatics.

There are watershed regions in the peritoneal cavity that are areas of fluid stasis:

- Ileocolic region

- Root of the sigmoid mesentery

- Pouch of Douglas

When you are staging a patient for gastrointestinal malignancy you have to look for disease in these areas of stasis.

Clearly the surgeons do better in finding subtle disease in these areas.

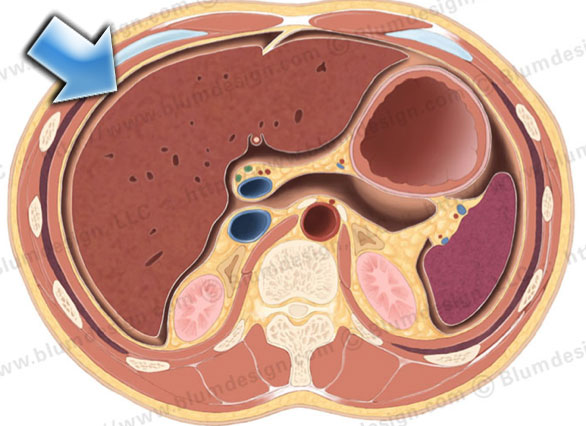

The majority of the peritoneal fluid is cleared at the subphrenic space (arrow) by the submesothelial lymphatics

The majority of the peritoneal fluid is cleared at the subphrenic space (arrow) by the submesothelial lymphatics

90% of peritoneal fluid is cleared at the subphrenic space by the submesothelial lymphatics.

These lymphatics are connected with lymphatics at the other side of the diafragm.

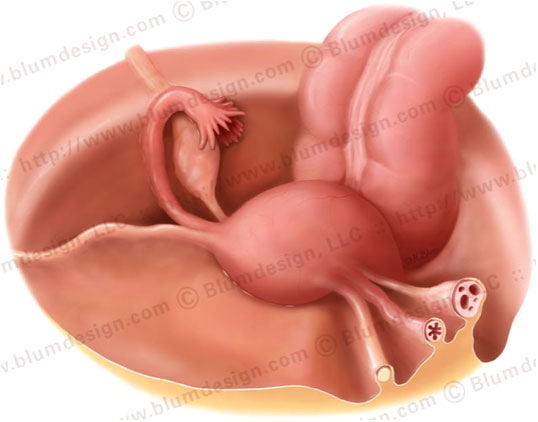

The peritoneum is continuous in the male pelvis.

In women the peritoneum is discontinuous at the ostia of the oviducts.

Through this opening disease can spread from the extraperitoneal pelvis into the peritoneal cavity.

For example, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

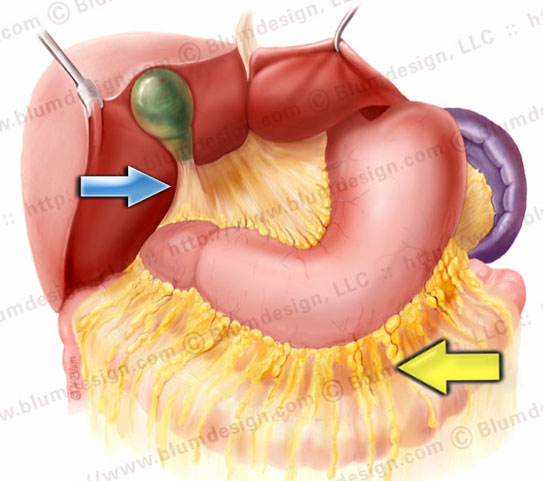

Gastrocolic ligament (yellow arrow), gastrosplenic ligament, gastrohepatic ligament and hepatoduodenal ligament (blue arrow

Gastrocolic ligament (yellow arrow), gastrosplenic ligament, gastrohepatic ligament and hepatoduodenal ligament (blue arrow

Omentum

The omentum is divided into the greater and lesser omentum.

The greater omentum is subdivided into:

- Gastrocolic ligament (yellow arrow): the largest component

- Gastrosplenic ligament: up to the hilus of the spleen

- Gastrophrenic ligament: not shown on this illustration

The lesser omentum is subdivided into:

- Gastrohepatic ligament: connects the left lobe of the liver to the lesser curvature of the stomach.

- Hepatoduodenal ligament (blue arrow): free edge of the omentum, which contains the portal vein, hepatic artery and common bile duct .