Elbow fractures in Children

Robin Smithuis

Radiology department, Rijnland Hospital Leiderdorp, the Netherlands.

Publicationdate

Elbow fractures are the most common fractures in children.

The assessment of the elbow can be difficult because of the changing anatomy of the growing skeleton and the subtility of some of these fractures.

In this review important signs of fractures and dislocations of the elbow will be discussed.

Before reading this article you can try one of the cases in the menubar.

You can test your knowledge on pediatric elbow fractures with these interactive cases.

On some of the images you can click to get a larger view. This does not work for the iPhone application

If you want to use images in a presentation, please mention the Radiology Assistant.

Fracture mechanism

Hyperextension

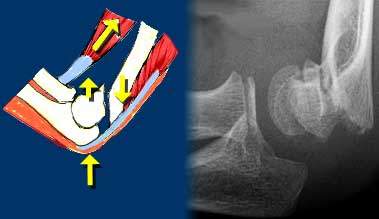

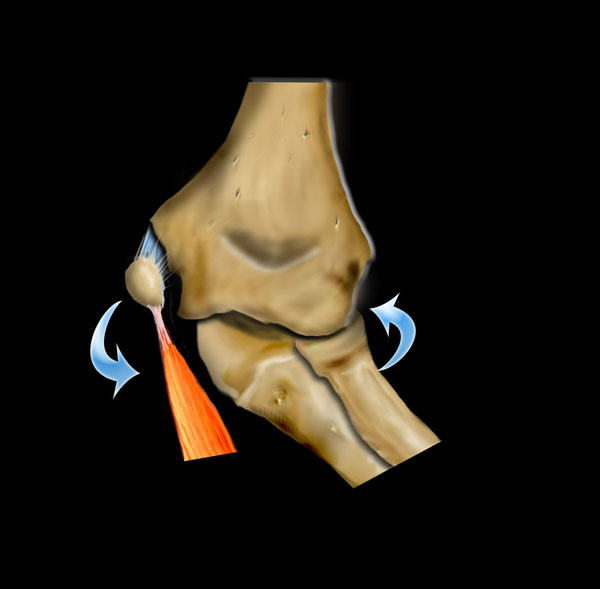

Injury to the elbow joint is usely the result of hyperextension or extreme valgus due to a fall on the outstretched arm.

Scroll through the images on the left to see how hyperextension leads to a supracondylar fracture.

The hemarthros will result in a displacement of the anterior fat pad upwards and the posterior fat backwards.

Extreme valgus

The other important fracture mechanism is extreme valgus of the elbow.

The normal elbow already has a valgus positioning.

When a child falls on the outstrechted arm, this can lead to extreme valgus.

On the lateral side this can result in a dislocation or a fracture of the radius with or without involvement of the olecranon.

When the forces have more effect on the humerus, the extreme valgus will result in a fracture of the lateral condyle.

On the medial side the valgus force can lead to avulsion of the medial epicondyle.

Sometimes the medial epicondyl becomes trapped within the joint.

Because of the valgus position of the normal elbow an avulsion of the lateral epicondyle will be uncommon.

Radiological Interpretation

Methodical review

When looking at radiographs of the elbow after trauma a methodical review of the radiographs is needed .

You should ask yourself the following important questions.

Is there a sign of joint effusion?

After trauma this almost always indicates the presence of hemarthros due to a fracture (either visible or occult).

Is there a normal alignment between the bones?

In children dislocations are frequent and can be very subtle.

Are the ossification centres normal?

Is the piece of bone that you're looking at a normal ossification centre and is this ossification centre in the normal position. .

Look especially for the position of the radial epiphysis and the medial epicondyle (figure).

Is there a subtle fracture?

Some of the fractures in children are very subtle.

So you need to be familiar with the typical picture of these fractures. .

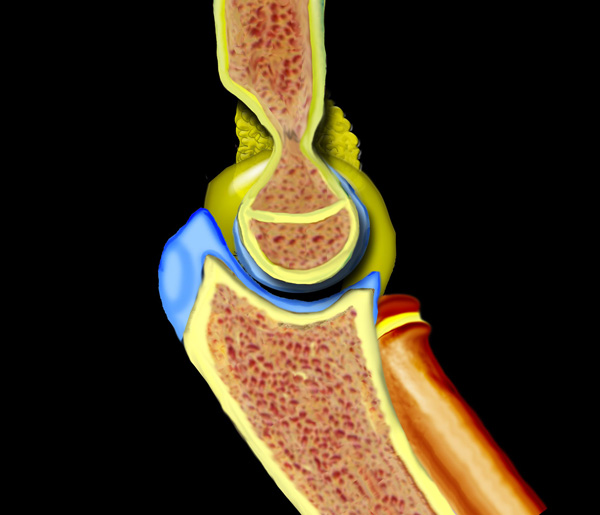

Fat Pad Sign and Joint effusion

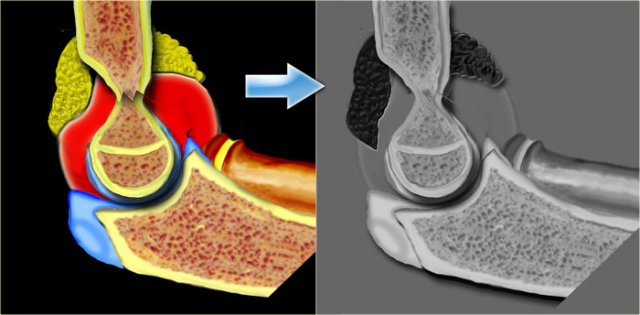

Normally on a lateral view of the elbow flexed in 90? a fat pad is seen on the anterior aspect of the joint .

This is normal fat located in the joint capsule.

On the posterior side no fat pad is seen since the posterior fat is located within the deep intercondylar fossa.

Positive fat pad sign

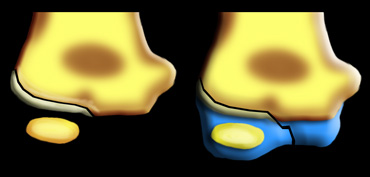

Distention of the joint will cause the anterior fat pad to become elevated and the posterior fat pad to become visible.

An elevated anterior lucency or a visible posterior lucency on a true lateral radiograph of an elbow flexed at 90? is described as a positive fat pad sign (figure).

Hemarthros results in an upward displacement of the anterior fat pad and a backward displacement the posterior fat.

Positive Anterior Fat Pad sign. On digital radiographs you may need to adjust the window width and level to appreciate this. No fracture was visible on the X-rays.

Positive Anterior Fat Pad sign. On digital radiographs you may need to adjust the window width and level to appreciate this. No fracture was visible on the X-rays.

Positive fat pad sign (2)

Any elbow joint distention either hemorrhagic, inflammatory or traumatic gives rise to a positive fat pad sign.

If a positive fat pad sign is not present in a child, significant intra-articular injury is unlikely.

A visible fat pad sign without the demonstration of a fracture should be regarded as an occult fracture.

These patients are treated as having a nondisplaced fracture with 2 weeks splinting.

Skaggs et al repeated x-rays after three weeks in patients with a positive posterior fat pad sign but no visible fracture.

They found evidence of fracture in 75%.

They concluded that in trauma displacement of the posterior fat pad is virtually pathognomonic of the presence of a fracture.

Displacement of the anterior fat pad alone however can occur due to minimal joint effusion and is less specific for fracture.

Notice that the elbow is not positioned well.

Try to find out what went wrong in the chapter on positioning.

Alignment

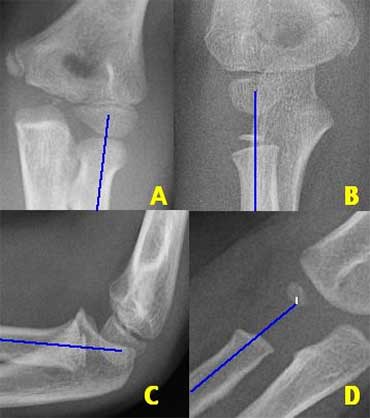

There are two important lines which help in the diagnosis of dislocation and fracture .

These are the Radiocapitellar line and the Anterior humeral line.

Radiocapitellar line

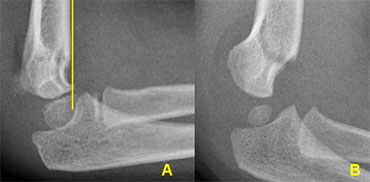

A line drawn through the centre of the radial neck should pass throught the centre of the capitellum, whatever the positioning of the patient, since the radius articulates with the capitellum (figure).

In dislocation of the radius this line will not pass through the centre of the capitellum.

On the left we see, that the radiocapitellar line goes through centre of the capitellum on every radiogragh even though C and D are not well positioned.

Notice supracondylar fracture in B.

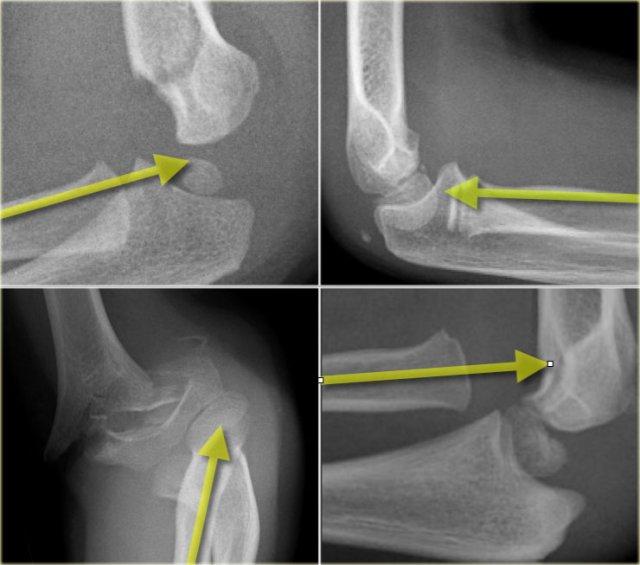

On the left more examples of the radiocapitellar line.

The right lower image shows an obvious dislocation of the radius.

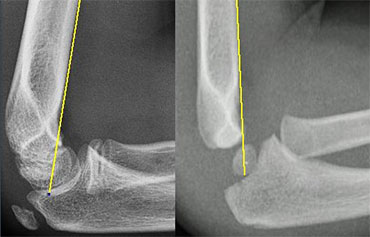

Radiographs of elbows at different ages. The Anterior Humeral line goes through the middle third of the capitellum .

Radiographs of elbows at different ages. The Anterior Humeral line goes through the middle third of the capitellum .

Anterior humeral line.

A line drawn on a lateral view along the anterior surface of the humerus should pass through the middle third of the capitellum..

This line is called the Anterior Humeral line .

In cases of a supracondylar fracture the anterior humeral line usually passes through the anterior third

of the capitellum or in front of the capitellum due to posterior bending of the distal humeral fragment.

On the left the anterior humeral line passes through the anterior third of the capitellum.

This indicates that the condyles are displaced dorsally (i.e. supracondylar fracture).

First study the images on the left.

Then continue reading.

The radiocapitellar line ends above the capitellum.

This means that the radius is dislocated.

Did you also notice the olecranon fracture?

Whenever the radius is fractured or dislocated, always study the ulna carefully.

Ossification centres

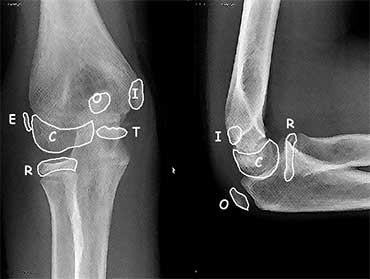

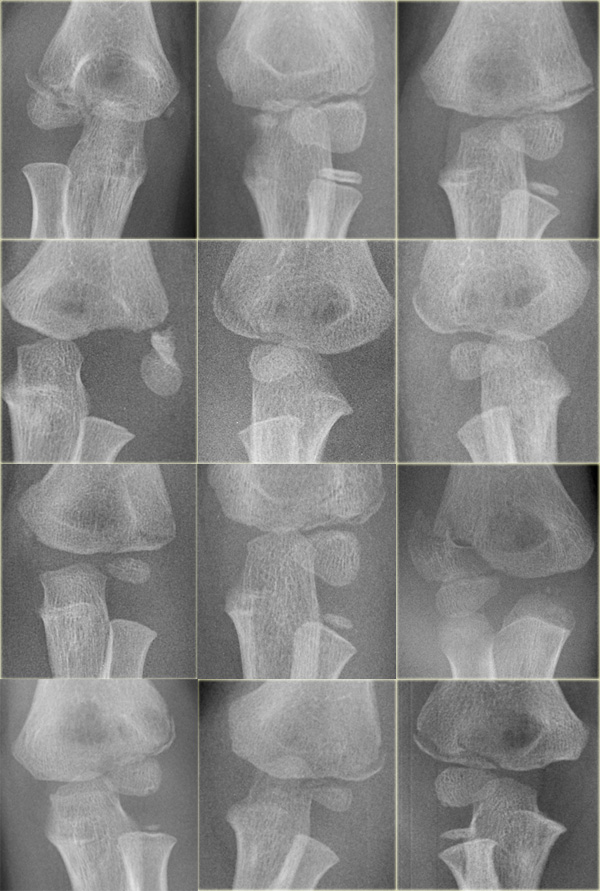

There are 6 ossification centres around the elbow joint.

They appear and fuse to the adjacent bones at different ages.

It is important to know the sequence of appearance since the ossification centers always appear in a strict order.

This order of appearance is specified in the mnemonic C-R-I-T-O-E

(Capitellum - Radius - Internal or medial epicondyle - Trochlea - Olecranon - External or lateral epicondyle).

The ages at which these ossification centres appear are highly variable and differ between individuals.

It is not important to know these ages, but as a general guide you could remember 1-3-5-7-9-11 years.

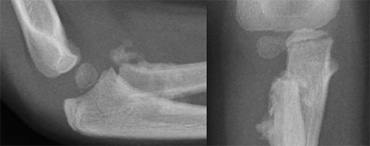

The Trochlea has two or more ossification centres which can give the trochlea a fragmented appearance.

On a lateral view the trochlea ossifications may project into the joint.

They should not be mistaken for loose intra-articular bodies (arrow).

Radiography

Common errors in positioning

Error 1: Shoulder higher than elbow

For a true lateral view the shoulder should be at the level of the elbow.

If the shoulder is higher than the elbow, the radius and capitellum will project on the ulna.

The solution is either to lift the examination table which will lift the elbow or to lower the shoulder by placing the patient on a smaller chair.

LEFT: Slight endorotation of the humerus due to a low position of the wrist. RIGHT: More endorotation due to malpositioning.

LEFT: Slight endorotation of the humerus due to a low position of the wrist. RIGHT: More endorotation due to malpositioning.

Error 2: Wrist lower than elbow

On the left two examples of a 'low wrist positioning' leading to rotation of the humerus.

The low position of the wrist leads to endorotation of the humerus.

The lateral structures like the capitellum and the radius will move anteriorly, while a medial structure like the medial epicondyle will move posteriorly.

The wrist should be higher than the elbow to compensate for the normal valgus position of the elbow.

The hand should be with the 'thumb up'.

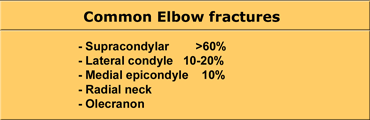

Elbow fractures

Supracondylar fractures

These fractures account for more than 60% of all elbow fractures in children (see Table).

More than 95% of supracondylar fractures are hyperextension type due to a fall on the outstretched hand.

The elbow becomes locked in hyperextension.

The olecranon is pushed into the olecranon fossa causing the anterior humeral cortex to bend and eventually break.

If the force continues both the anterior and posterior cortex will fracture.

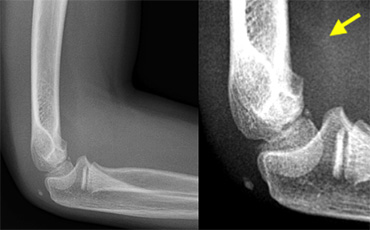

Supracondylar fractures. In A the anterior humeral line passes through the anterior third of the capitellum and in B even more anteriorly. Notice positive posterior fat pad sign in both cases

Supracondylar fractures. In A the anterior humeral line passes through the anterior third of the capitellum and in B even more anteriorly. Notice positive posterior fat pad sign in both cases

Supracondylar fractures (2)

If there is only minimal or no displacement these fractures can be occult on radiographs.

The only sign will be a positive fat pad sign.

Usually there is some displacement and the anterior humeral line will not pass through the centre of the capitellum but through the anterior third or even anterior to the capitellum (figure).

Supracondylar fractures (3)

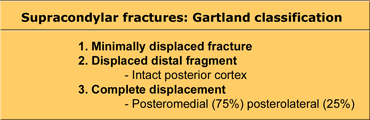

Supracondylar fractures are classified according to Gartland.

Gartland Type I fractures are often difficult to see on X-rays since there is only minimal displacement.

Most of these fractures consist of greenstick or torus fractures.

The only clue to the diagnosis may be a positive fat pad sign.

These patients are treated with casting.

In Gartland type II fractures there is displacement but the posterior cortex is intact.

There may be some rotation. These fractures require closed reduction and some need percutaneous fixation if a long-arm cast does not adequately hold the reduction.

Gartland type III fractures are completely dislocated and are at risk for malunion and neurovascular complications (figure).

They require reduction by closed or if necessary open means. Stabilisation is maintained with either two lateral pins or medial lateral cross pin technique.

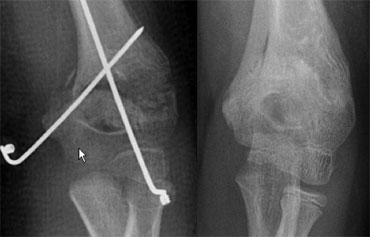

Gartland III fracture with medial-lateral cross pin technique. After reduction there is inadequate correction of medial collaps. After two months there is malunion with cubitus varus deformity.

Gartland III fracture with medial-lateral cross pin technique. After reduction there is inadequate correction of medial collaps. After two months there is malunion with cubitus varus deformity.

Supracondylar fractures (4)

Malunion will result in the classic 'gunstock' deformity due to rotation or inadequate correction of medial collaps.

Posterolateral displacement of the distal fragment can be associated with injurie to the neurovascular bundle which is displaced over the medial metaphyseal spike.

Nerve injurie almost always results in neuropraxis that resolves in 3-4 months.

Vascular injurie usually results in a pulseless but pink hand.

Conservative management and vascular intervention have the same outcome.

A pulseless and white hand after reduction needs exploration.

Supracondylar fractures (5)

Flexion-type fractures are uncommon (5% of all supracondylar fractures).

They are caused by direct impact on the flexed elbow.

Ulnar nerve injury is more common.

Compared to extension types, they are more likely to be unstable, so more likely to require fixation.

Lateral Condyle fractures

This fracture is the second most common distal humerus fracture in children.

They occur between the ages of 4 and 10 years.

These fractures occur when a varus force is applied to the extended elbow.

They tend to be unstable and become displaced because of the pull of the forearm extensors.

Since these fractures are intra-articular they are prone to nonunion because the fracture is bathed in synovial fluid.

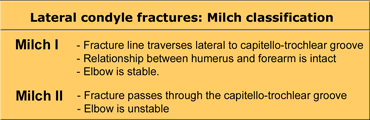

Lateral condyle fractures are classified according to Milch. They are Salter-Harris IV epiphysiolysis fractures.

Most are Milch II fractures that travel from the lateral humeral metaphysis above the epiphysis and exit through the lateral crista of the trochlea leading to an unstable humeral ulnar articulation.

Lateral Condyle fractures (2)

The problem with the Milch-classification is the fact that the fracture fragments are primarily cartilaginous. The fracture line through the cartilage is not visible on radiographs, so the radiographic interpretation concerning classification is difficult.

Treatment strategies are therefore based on the amount of displacement (see Table).

Undisplaced fractures are treated with a long arm cast.

These fractures must be carefully monitored as they have a tendency to displace. At follow up both AP and Oblique views are taken after removal of the cast.

Once displaced fractures consolidate in a malunited position, treatment is difficult and fraught with complications.

For this reason surgical reductions is recommended within the first 48 hours.

Open reduction is indicated for all displaced fractures and those demonstrating joint instability.

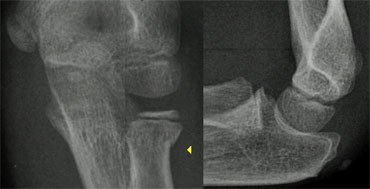

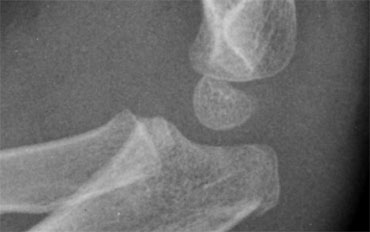

Lateral Condyle fractures (3) .

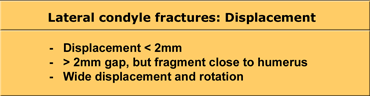

The diagnosis of a lateral condyle fracture can be challenging.

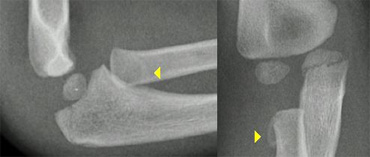

Fracture lines are sometimes barely visible (figure).

Remembering the fact that the lateral condyle fracture is the second most common elbow-fracture in children and because you know where to look for will help you

Lateral condyle fracture. On the x-ray only a small metaphyseal fragment is visible. The detatched fragment however is larger than it appears on the radiograph. The fracture extents into the lateral ridge of the trochlea. Elbow is probably unstable.

Lateral condyle fracture. On the x-ray only a small metaphyseal fragment is visible. The detatched fragment however is larger than it appears on the radiograph. The fracture extents into the lateral ridge of the trochlea. Elbow is probably unstable.

Lateral Condyle fractures (4) .

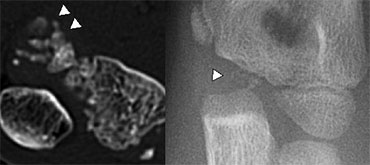

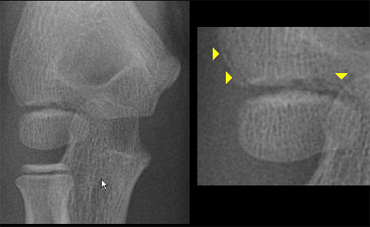

Since most of the structures involved are cartilageneous, it is very difficult to know the exact extent of the fracture.

Sometimes the fracture runs through the ossified part of the capitellum. In those cases it is easy.

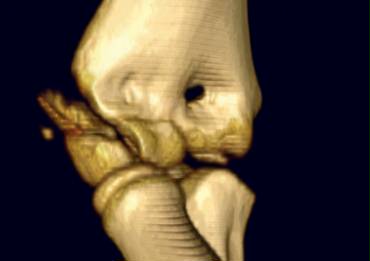

The case on the left shows a lateral condyle fracture extending through the ossified part of the capitellum.

This is a Milch I fracture. The elbow is stable.

There is too much displacement so osteosynthesis has to be performed.

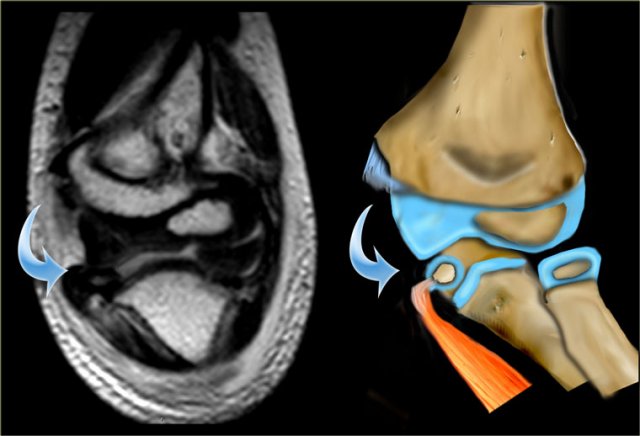

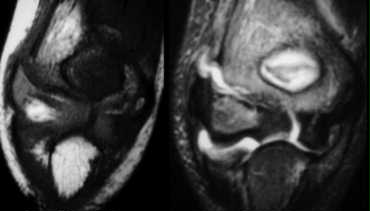

MR of lateral condyle fracture. Milch II and unstable elbow. T2 image with fat saturation on the right shows cartilaginous fracture. Fracture-fragment surrounded by synovial fluid. (Courtesy of Lynne Steinbach, M.D. Univ. of California, San Francisco)

MR of lateral condyle fracture. Milch II and unstable elbow. T2 image with fat saturation on the right shows cartilaginous fracture. Fracture-fragment surrounded by synovial fluid. (Courtesy of Lynne Steinbach, M.D. Univ. of California, San Francisco)

MRI can be helpfull in depicting the full extent of the cartilaginous component of the fracture.

The case on the left shows a fracture extending into the unossified trochlear ridge.

The fracture through the trochlear cartilage is so far medial that the ulna is only supported on the medial side.

This means that the elbowjoint is unstable.

LEFT a subtle lateral condyle fracture. Less than 2 mm displacement and probably stable. RIGHT a different case. Oblique view gives nice impression of fracture. Blue arrow indicates a cleft epiphysis of the radius (normal variant)

LEFT a subtle lateral condyle fracture. Less than 2 mm displacement and probably stable. RIGHT a different case. Oblique view gives nice impression of fracture. Blue arrow indicates a cleft epiphysis of the radius (normal variant)

Lateral Condyle fractures (5)

In lateral condyle fractures the actual fracture line can be very subtle since the metaphyseal flake of bone may be minor.

The fracture fragment is often rotated.

An oblique view can be helpfull, but usually these are not routinely performed (figure).

Two cases of overprojection of the capitellum on humeral epiphysis simulating a fracture. Notice olecranon fracture on the right

Two cases of overprojection of the capitellum on humeral epiphysis simulating a fracture. Notice olecranon fracture on the right

Lateral Condyle fractures (6) .

Overprojection of the capitellum on the humeral metaphysis may simulate a lateral condyle fracture (figure).

Lateral Condyle fractures (7) .

On the left a couple of examples of lateral condyle fractures.

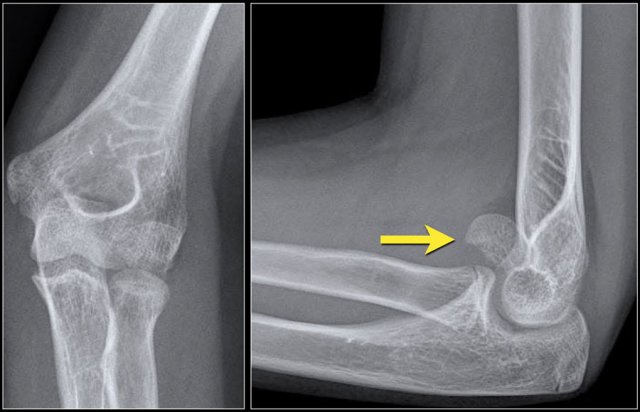

Capitellum fracture

While fractures of the lateral condyle occur in children between the age of 4 -10 years, isolated fractures of the capitellum are seen in children above the age of 12.

Capitellum fractures are uncommon.

The rotation of the fracture fragment gives a typical appearance on the X-rays (arrow).

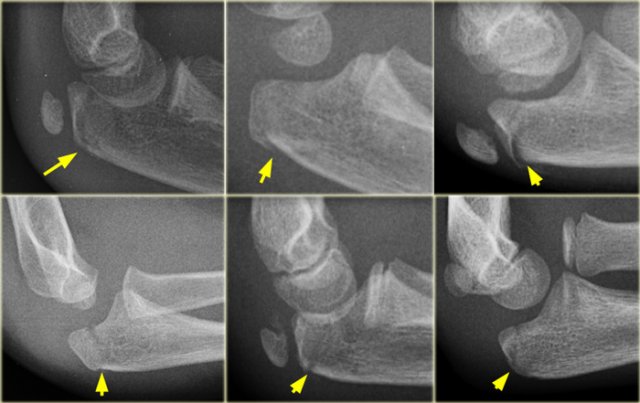

Normal medial epicondyle projecting posteriorly. Notice radial head dislocation and olecranon fracture

Normal medial epicondyle projecting posteriorly. Notice radial head dislocation and olecranon fracture

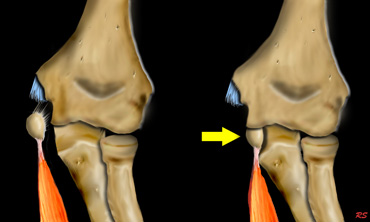

Medial Epicondyle avulsion

The medial epicondyle is an apophysis since it does not contribute to the longitudinal growth of the humerus.

It is located on the dorsal side of the elbow.

On a lateral view especially if the arm is endorotated it can project so far posteriorly that one could suggest an avulsion (figure).

However avulsions are located more distally and anteriorly.

Since the medial epicondyle is an extra-articular structure a fracture or avulsion will not automatically produce a positive fat pad sign.

Medial Epicondyle avulsion (2).

80% of avulsion fractures occur in boys with a peak age in early adolescence.

The mechanism is an acute valgus stress due to a fall on the outstretched hand or sometimes due to armwrestling.

Chronic injuries do occur in young athletes (little league elbow).

The mechanism that causes these stressfractures on the medial side is the same mechanism that causes a osteochondritis of the capitellum due to impaction on the lateral side.

Medial Epicondyle avulsion (3).

There is a 50% incidence of associated elbow dislocations.

When the elbow is dislocated and the medial epicondyle is avulsed,

it may become interposed between the articular surface of the humerus and the olecranon (figure).

In every dislocation the first question should be 'where is the medial epicondyle'.

Same case as above. After reduction the epicondyle returned to its normal position (not good visible due to cast) and was fixated with K-wires.

Same case as above. After reduction the epicondyle returned to its normal position (not good visible due to cast) and was fixated with K-wires.

On reducing the elbow the fragment may return to it's original position or remain trapped in the joint.

This may severely damage the articular surface.

So post-reduction films should be studied carefully.

Medial Epicondyle avulsion (4).

Due to the extreme valgus force the joint may temporarily open.

The avulsed fragment may become entrapped in the joint even when there is no dislocation of the elbow.

On AP-view the avulsed medial epicondyle projects over the trochlea. Lateral view shows the fragment to be trapped within the joint.

On AP-view the avulsed medial epicondyle projects over the trochlea. Lateral view shows the fragment to be trapped within the joint.

Medial Epicondyle avulsion (5).

An avulsed fragment that is located within the joint can give diagnostic problems.

On an AP-view this fragment may be overlooked (figure).

When the trochlea is not yet ossified the avulsed fragment may simulate a trochlear ossification centre.

Another example of a dislocated elbow with avulsion of the medial epicondyle. In this case the epicondyle is not retracted into the joint.

Another example of a dislocated elbow with avulsion of the medial epicondyle. In this case the epicondyle is not retracted into the joint.

Medial Epicondyle avulsion (6).

Treatment

Non-displaced fractures are treated with 1-2 weeks cast or splint.

There is disagreement about the amount of displacement of the medial epicondyle that requires operative fixation.

There is support for both operative aswell as non-operative management of medial epicondyle fractures with 5-15mm displacement.

Avulsion of the medial epicondyle. The amount of soft tissue swelling on the medial side suggests that the elbow was dislocated.

Avulsion of the medial epicondyle. The amount of soft tissue swelling on the medial side suggests that the elbow was dislocated.

Medial Epicondyle avulsion (7).

If the history or the radiographs suggest that the elbow was or is dislocated, greater soft tissue injurie is likely to be present requiring need for early motion.

Medial Epicondyle avulsion (8).

Study the images.

You can click on the image to enlarge.

There are three findings, that you should comment on.

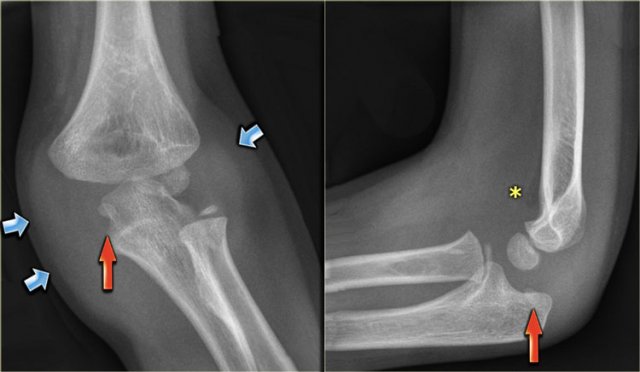

- There is enormous soft tissue swelling, which indicates that the elbow has been dislocated (blue arrows). So the next question is where is the medial epicondyle?

- The medial epicondyle is seen entrapped within the joint (red arrows).

- Notice that there is only minor joint effusion (asterix). The medial epicondyle is an extra-articular structure and avulsion will not produce joint effusion. The small amount of joint effusion is probably the result of the prior dislocation.

Continue with the MRI.

The MR shows the small medial epicondyle with tendon attachement trapped within the joint.

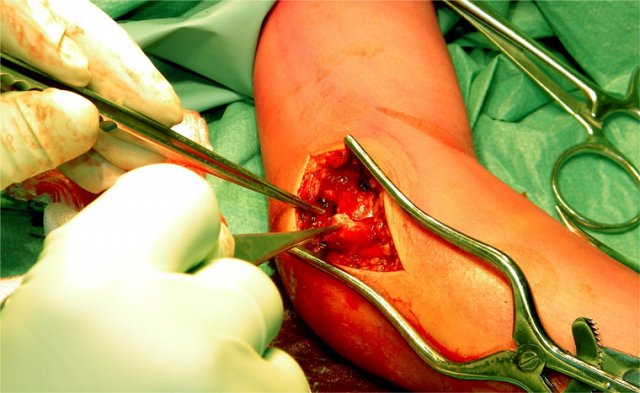

The avulsed medial epicondyl was found within the joint and repositioned and fixated with K-wires.

Proximal fractures of the Radius

In adults fractures usually involve the articular surface of the radial head.

In children however it's the radial neck that fractures because the metaphyseal bone is weak due to constant remodelling.

Usually it is a Salter Harris II fracture.

If there is no displacement it can be difficult to make the diagnosis (figure).

Radial neck fracture with tilt. Notice trochlear ossifications projecting in between humerus and ulna simulating intra-articular fragments.

Radial neck fracture with tilt. Notice trochlear ossifications projecting in between humerus and ulna simulating intra-articular fragments.

If there is less than 30? tilt of the radial head patients are treated with a collar.

It is important to realize that there is normally some angulation of the radial head ( up to 15?).

If there is more than 30? tilt closed reduction is performed.

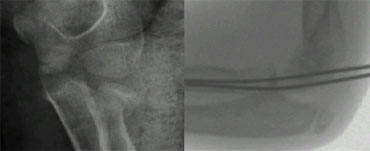

After closed reduction radiograph in cast shows unsuccesfull reduction. K-wire insertion is performed

After closed reduction radiograph in cast shows unsuccesfull reduction. K-wire insertion is performed

Whenever closed reduction is unsuccesfull in restoring tilt or when it is not possible to pronate and supinate up to 60?, a K-wire is inserted to maintain reduction.

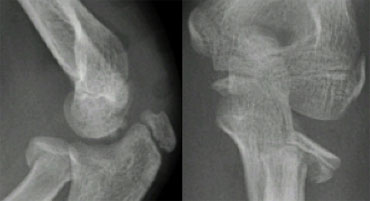

The radial epiphysis is slipped (arrows). The radiocapitellar line does not pass through the capitellum indicating dislocation and there is a fracture of the olecranon

The radial epiphysis is slipped (arrows). The radiocapitellar line does not pass through the capitellum indicating dislocation and there is a fracture of the olecranon

Radial neck fractures aswell as radial head dislocations are in 50% of the cases associated with other elbow injuries.

The most common is a fracture of the olecranon.

When the radial epiphysis is yet very small a slipped radial epiphysis may be overlooked (figure).

If these fractures are not recognized or reduction is unsuccesfull radial head overgrowth can be the result.

A short radius may also be the result since the epiphysis of the radius contributes to the length growth of the radius.

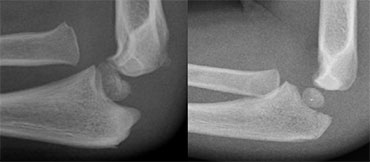

LEFT: an obvious radial dislocation. No fracture of the ulna (Monteggia) was foundRIGHT: a subtle radial head dislocation. Associated olecranonfracture is seen on carefull inspection

LEFT: an obvious radial dislocation. No fracture of the ulna (Monteggia) was foundRIGHT: a subtle radial head dislocation. Associated olecranonfracture is seen on carefull inspection

Dislocations of the Radial head

Dislocations of the radial head can be very obvious.

It is however not uncommon that these dislocations are subtle and easily overlooked.

In all cases one should look for associated injury.

In the original discription of Monteggia there is a radial dislocation in combination with a proximal ulnar shaft fracture.

However fractures anywhere along the ulna have been reported.

Especially associated fractures of the olecranon are very common (figure).

Radius Pulled Elbow (Nursemaid's elbow)

In children When the forearm is pulled the radial head moves distally and the ligament slips over the radial head and becomes trapped within the joint. The X-ray is normal.

The condition is cured by supination of the forearm. Sometimes this happens during positioning for a true lateral view (which is with the forearm in supination).

Olecranon fractures

Olecranon fractures in children are less common than in adults. As discussed above they are associated with radial neck fractures and radial dislocations.

Olecranon fractures (2)

Do not mistake the apophysis or its separate ossification centres for a fracture.

The apophysis has undulating faintly sclerotic margins.

The growth plate usually has a different oblique course compared to a fracture-line.

Olecranon fractures (3)

On the left some examples of fractures of the olecranon.

Notice how subtle some of these fractures are.

Conclusion

Whenever you study a radiograph of the elbow of a child, always look for:

- Supracondylar fracture with minimal displacement

- Lateral condyle fracture

- Slipped radial epiphysis

- Radial dislocation

- Position of the medial epicondyle.