Vascular territories of the Brain

Robin Smithuis

Radiology department of the Alrijne Hospital in Leiderdorp, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

Knowledge of the vascular territories is important, because it enables you to recognize infarctions in arterial territories, in watershed regions and also venous infarctions.

It also helps you to differentiate infarction from other pathology.

Cerebral Arterial Territory

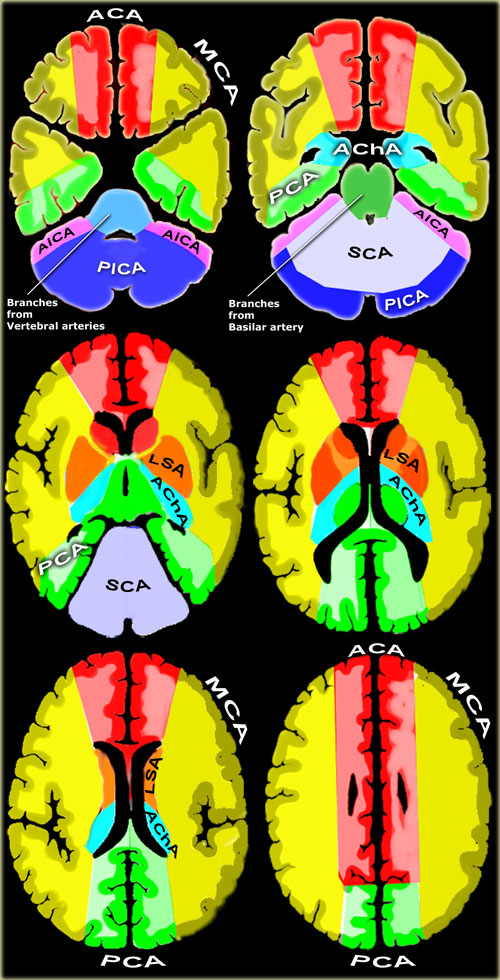

Vascular territories of the cerebral arteries (adapted and modified with permission from M. Savoiardo (1)

Vascular territories of the cerebral arteries (adapted and modified with permission from M. Savoiardo (1)

- Posterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery (PICA in blue)

The PICA territory is on the inferior occipital surface of the cerebellum and is in equilibrium with the territory of the AICA in purple, which is on the lateral side (1).

The larger the PICA territory, the smaller the AICA and viceversa. - Superior Cerebellar Artery (SCA in grey)

The SCA territory is in the superior and tentorial surface of the cerebellum. - Branches from vertebral and basilar artery

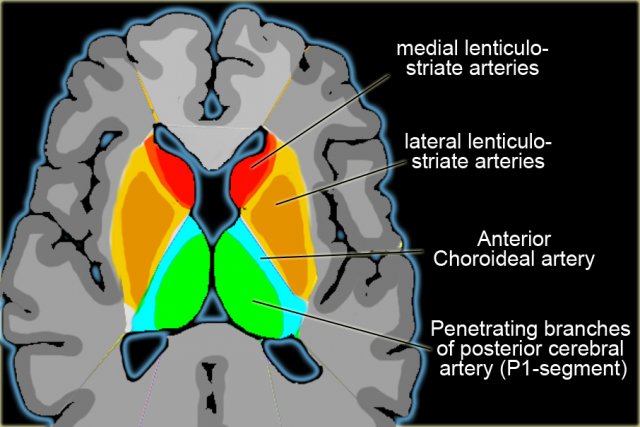

These branches supply the medulla oblongata (in blue) and the pons (in green). - Anterior Choroideal artery (AchA in blue))

The territory of the AChA is part of the hippocampus, the posterior limb of the internal capsule and extends upwards to an area lateral to the posterior part of the cella media. - Lenticulo-striate arteries

The lateral LSA' s (in orange) are deep penetrating arteries of the middle cerebral artery (MCA).

Their territory includes most of the basal ganglia.

The medial LSA' s (indicated in dark red) arise from the anterior cerebral artery (usually the A1-segment).

Heubner's artery is the largest of the medial lenticulostriate arteries and supplies the anteromedial part of the head of the caudate and anteroinferior internal capsule. - Anterior cerebral artery (ACA in red)

The ACA supplies the medial part of the frontal and the parietal lobe and the anterior portion of the corpus callosum, basal ganglia and internal capsule. - Middle cerebral artery (MCA in yellow)

The cortical branches of the MCA supply the lateral surface of the hemisphere, except for the medial part of the frontal and the parietal lobe (anterior cerebral artery), and the inferior part of the temporal lobe (posterior cerebral artery).

The deep penetrating LSA-branches are discussed above. - Posterior cerebral artery (PCA in green)

P1 extends from origin of the PCA to the posterior communicating artery, contributing to the circle of Willis.

Posterior thalamoperforating arteries branch off the P1 segment and supply blood to the midbrain and thalamus.

Cortical branches of the PCA supply the inferomedial part of the temporal lobe, occipital pole, visual cortex, and splenium of the corpus callosum.

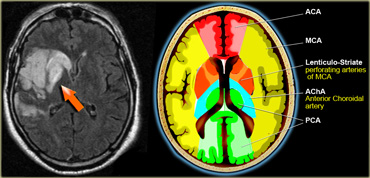

On the left a detail to illustrate the vascular supply to the basal ganglia.

PICA

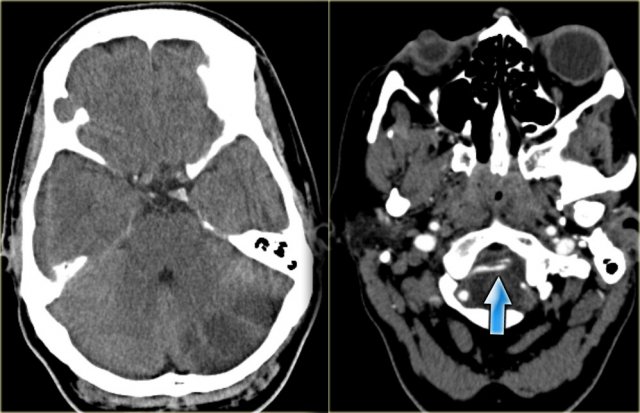

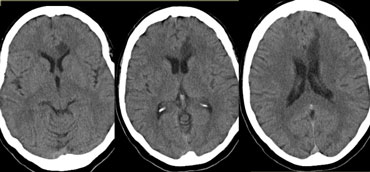

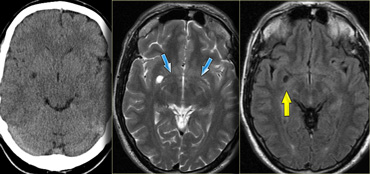

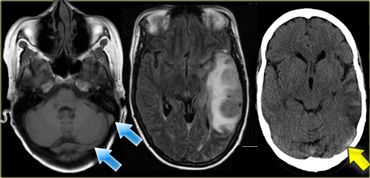

On the left CT-images of a left-sided PICA-infarction.

Notice the posterior extention.

The infarction was the result of a dissection (blue arrow).

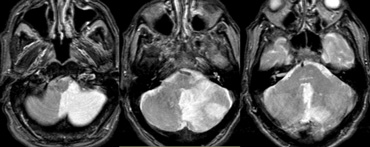

On the left MR-images of a left-sided PICA-infarction.

In unilateral infarcts there is always a sharp delineation in the midline because the superior vermian branches do not cross the midline, but have a sagittal course.

This sharp delineation may not be evident until the late phase of infarction.

In the early phase, edema may cross the midline and create diagnostic difficulties.

Infarctions at pontine level are usually paramedian and sharply defined because the branches of the basilar arery have a sagittal course and do not cross the midline.

Bilateral infarcts are rarely observed because these patients do not survive long enough to be studied, but sometimes small bilateral infarcts can be seen.

SCA

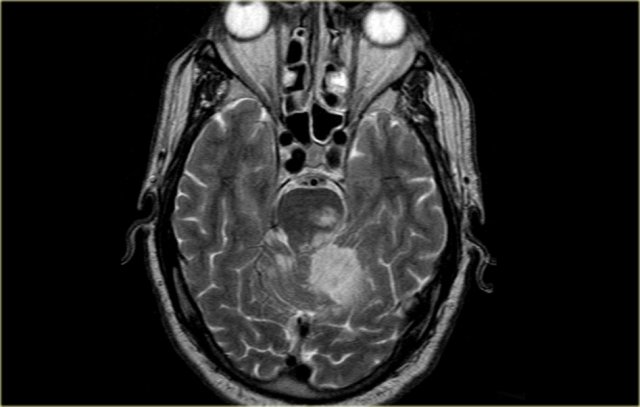

On the left MR-image of a cerebellar infarction in the region of the superior cerebellar artery and also in the brainstem in the territory of the PCA.

Notice the limitation to the midline.

ACA

Anterior cerebral artery:

- A1 segment: from origin to anterior communicating artery and gives rise to medial lenticulostriate arteries (inferior parts of the head of the caudate and the anterior limb of the internal capsule).

- A2 segment: from anterior communicating artery to bifurcation of pericallosal and callosomarginal arteries.

- A3 segment: major branches (medial portions of frontal lobes, superior medial part of parietal lobes, anterior part of the corpus callosum).

Anterior choroidal artery

The anterior choroidal artery originates from the internal carotid artery.

Rarely it arises from the middle cerebral artery.

The territory of the anterior choroidal artery encompasses part of the hippocampus, the posterior limb of the internal capsule and extends upwards to an area lateral to the posterior part of the cella media.

The whole area is rarely involved in AChA infarcts.

The posterior limb of the internal capsule also receives blood from the lateral lenticulostriate arteries.

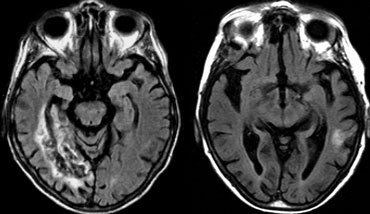

On the left an uncommon infarction in the hippocampal region.

Part of the territory of the anterior choroidal artery and the PCA are involved.

Middle cerebral artery

The MCA has cortical branches and deep penetrating branches, which are called the lateral lenticulo-striate arteries.

The territory of the lateral lenticulo-striate perforating arteries of the MCA is indicated with a different color from the rest of the territory of the MCA because it is a well-defined area supplied by penetrating branches, which may be involved or spared in infarcts separately from the main cortical territory of the MCA.

On the left a T2W-image of a patient with an infarction in the territory of the middle cerebral artery (MCA).

Notice that the lateral lenticulo-striate perforating arteries of the MCA are also involved (orange arrow).

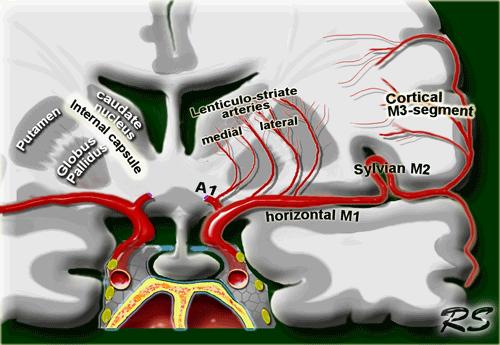

Lenticulostriate arteries

Medial lenticulostriate arteries

They are branches of the A1-segment of the anterior cerebral artery.

They supply the anterior inferior parts of the basal nuclei.

They also supply the anterior limb of the internal capsule together with the recurrent artery of Huebner, which also is a branch of the anterior cerebral artery.

Lateral lenticulostriate arteries

They are branches of the horizontal M1-segment of the middle cerebral artery.

They supply the superior part of the head and the body of the caudate nucleus, most of the globus pallidus and putamen.

They also supply the anterior limb of the internal capsule and parts of the posterior limb of the internal capsule, which is largely supplied by the anterior choroidal artery.

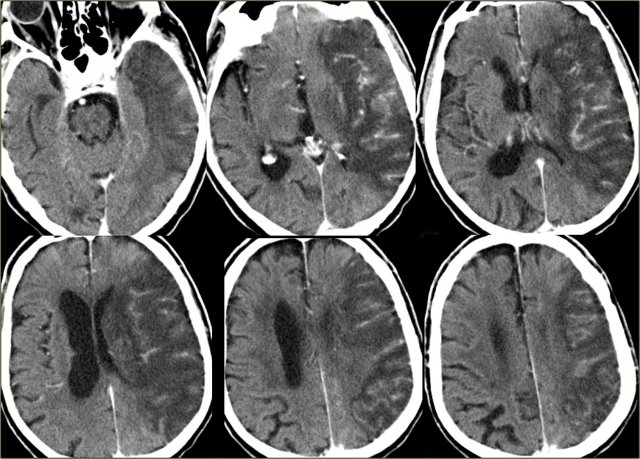

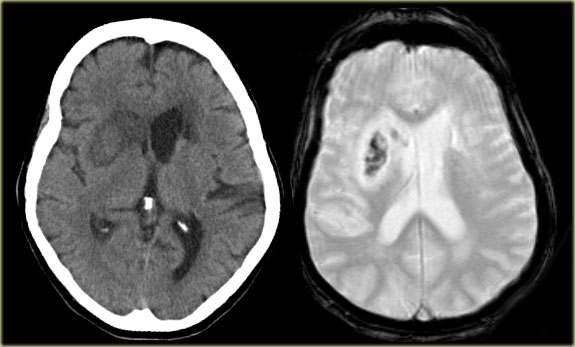

CT and T2W-gradient echo image of a hemorrhagic infarction limited to the territory of the lateral lenticulo-striate arteries

CT and T2W-gradient echo image of a hemorrhagic infarction limited to the territory of the lateral lenticulo-striate arteries

On the left images of a hemorrhagic infarction in the area of the deep perforating lenticulostriate branches of the MCA.

On the left enhanced CT-images of a patient with an infarction in the territory of the middle cerebral artery (MCA).

There is extensive gyral enhancement (luxury perfusion).

Sometimes this luxury perfusion may lead to confusion with tumoral enhancement.

Posterior cerebral artery (PCA)

Deep or proximal PCA strokes cause ischemia in the thalamus and/or midbrain, as well as in the cortex.

Superficial or distal PCA infarctions involve only cortical structures (4).

On the left a patient with acute vision loss in the right half of the visual field.

The CT demonstrates an infarction in the contralateral visual cortex, i.e left occipital lobe.

Only about 5% of ischemic strokes involve the PCA or its branches (3).

On the left CT-images of a patient with a PCA-infarction.

Notice the loss of gray/white matter differentiation in the regio of the left occipital lobe.

Variations in Arterial Territories

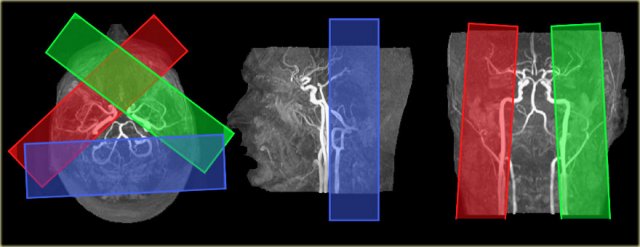

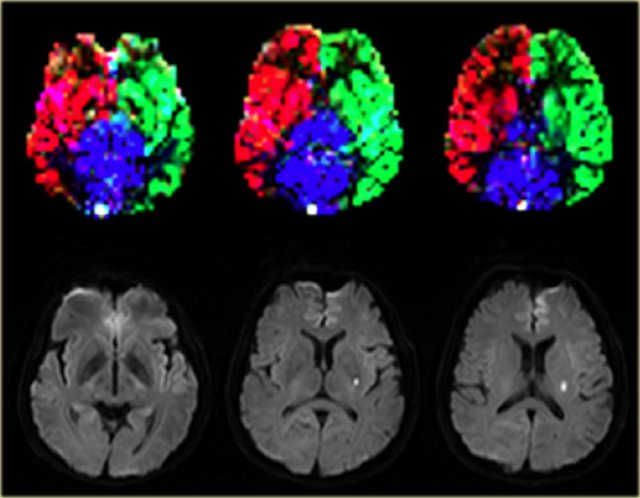

Variations in perfusion territories in the brain can be visualized with selective arterial spin-labeling (9).

The ability to visualize these perfusion territories is important in specific patient groups with cerebrovascular disease, such as acute stroke, large artery steno-occlusive disease, and arteriovenous malformation, as it provides valuable hemodynamic information.

On the left the time-of-flight MR angiography-images of brain-feeding arteries showing the planning of the selective slabs for perfusion territory imaging of the left and right internal carotid artery and the vertebrobasilar artery.

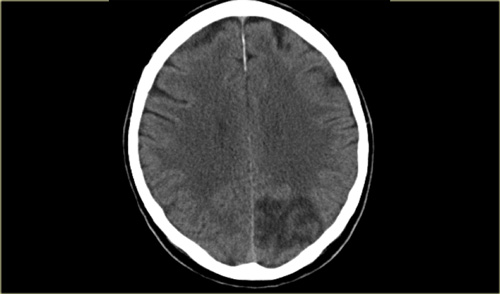

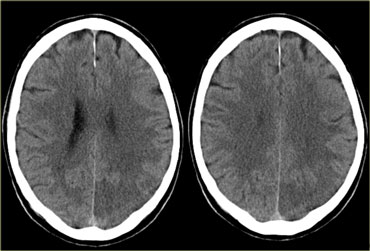

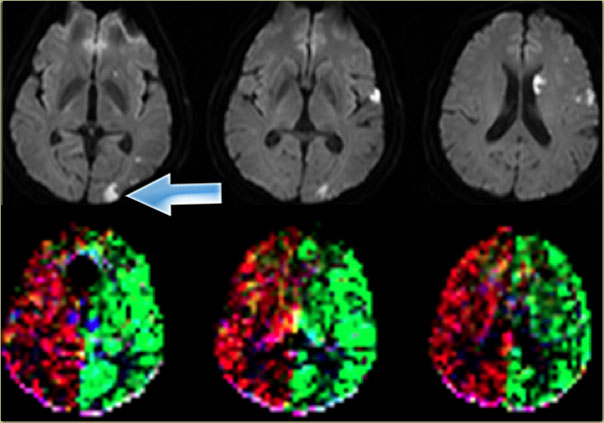

Normal perfusion territories in a patient with a lacunar infarction Images courtesy Jeroen Hendrikse (9)

Normal perfusion territories in a patient with a lacunar infarction Images courtesy Jeroen Hendrikse (9)

On the left a patient with a lacunar infarction on the left with normal perfusion territories.

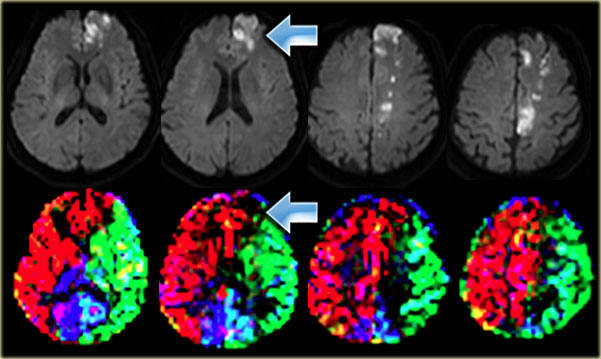

Cortical infarction in the left frontal lobe which is supplied by the right ICA Images courtesy Jeroen Hendrikse (9)

Cortical infarction in the left frontal lobe which is supplied by the right ICA Images courtesy Jeroen Hendrikse (9)

On the left a patient with a watershed infarct in the left hemisphere and also a cortical infarction in the left frontal lobe (arrow).

Notice that there is a variation in the brain perfusion since the left frontal lobe is supplied by the right internal carotid artery.

On the left another variation in the brain perfusion in a patient with multiple infarctions as demonstrated on the diffusion images.

There is a small cortical infarction in the left occipital lobe which happens to be perfused by the left internal carotid artery (arrow).

Notice that there is no contribution by the vertebrobasilar arteries.

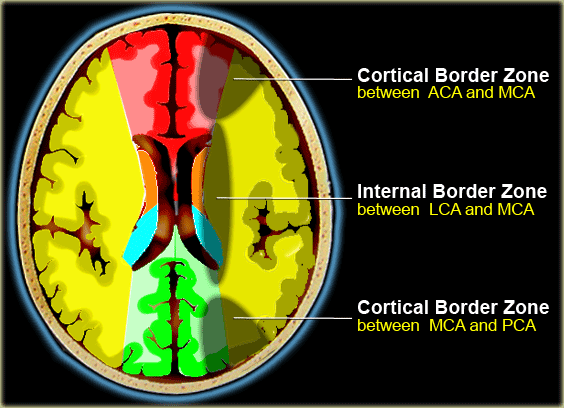

Watershed Infarcts

Watershed infarcts occur at the border zones between major cerebral arterial territories as a result of hypoperfusion.

There are two patterns of border zone infarcts:

- Cortical border zone infarctions

Infarctions of the cortex and adjacent subcortical white matter located at the border zone of ACA/MCA and MCA/PCA - Internal border zone infarctions

Infarctions of the deep white matter of the centrum semiovale and corona radiata at the border zone between lenticulostriate perforators and the deep penetrating cortical branches of the MCA or at the border zone of deep white matter branches of the MCA and the ACA.

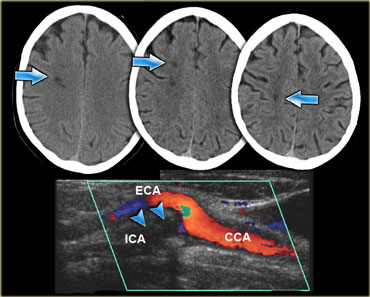

On the left three consecutive CT-images of a patient with an occlusion of the right internal carotid artery.

The hypoperfusion in the right hemisphere resulted in multiple internal border zone infarctions.

This pattern of deep watershed infarction is quite common and should urge you to examine the carotids.

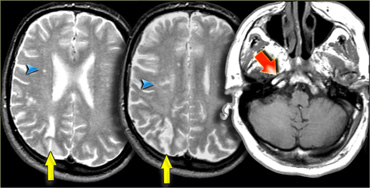

On the left images of a patient who has small infarctions in the right hemisphere in the deep borderzone (blue arrowheads) and also in the cortical borderzone between the MCA- and PCA-territory (yellow arrows).

There is abnormal signal in the right carotid (red arrow) as a result of occlusion.

In patients with abnormalities that may indicate borderzone infarcts, always study the images of the carotid artery to look for abnormal signal.

On the left another example of small infarctions in the deep borderzone and in the cortical borderzone between the MCA- and PCA-territory in the left hemisphere.

On the left an example of infarctions in the deep borderzone and in the cortical borderzone between the ACA- and MCA-territory.

The abnormal signal intensity in the right carotid is the result of an occlusion.

This combination of findings is so common, that once you know the pattern, you will see it many times.

Lacunar Infarcts

Lacunar infarcts are small infarcts in the deeper parts of the brain (basal ganglia, thalamus, white matter) and in the brain stem.

Lacunar infarcts are caused by occlusion of a single deep penetrating artery.

Lacunar infarcts account for 25% of all ischemic strokes.

Atherosclerosis is the most common cause of lacunar infarcts followed by emboli.

25% of patients with clinical and radiologically defined lacunes had a potential cardiac cause for their strokes.

On the left a T2W- and FLAIR image of a lacunar infarct in the left thalamus.

On the FLAIR image the infarct is hardly seen.

There is only a small area of subtle hyperintensity.

Lacunes may be confused with other empty spaces, such as enlarged perivascular Virchow-Robin spaces (VRS).

The VRS are extensions of the subarachnoid space that accompany vessels entering the brain parenchyma.

Widening of VRS often first occurs around penetrating arteries in the substantia perforata and can be seen on transverse MRI slices around the anterior commisure, even in young subjects (5).

On the left CT- and MR-images at the level of the anterior commisure (blue arrows).

On the CT there is a hypodense area in the right hemisphere, which follows the signal intensity of CSF on T2W- and FLAIR-images, which is typical for widened VRS.

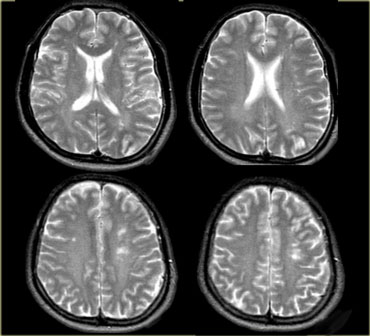

PRES

PRES is short for Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome.

It is also known as reversible posterior Leukoencephalopathy syndrome [RPLS].

It classically consists of potentially reversible vasogenic edema in the posterior circulation territories, but anterior circulation structures can also be involved (6).

Many causes have been described including hypertension, eclampsia and preeclampsia, immunosuppressive medications such as cyclosporine.

The mechanism is not entirely understood but is thought to be related to a hyperperfusion state, with blood-brain-barrier breakthrough, extravasation of fluid potentially containing blood or macromolecules, and resulting cortical or subcortical edema.

The typical imaging findings of PRES are most apparent as hyperintensity on FLAIR images in the parietooccipital and posterior frontal cortical and subcortical white matter; less commonly, the brainstem, basal ganglia, and cerebellum are involved.

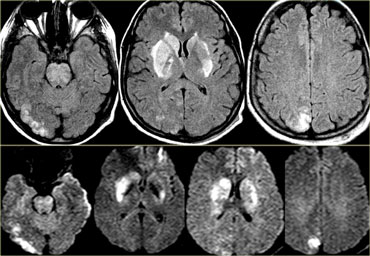

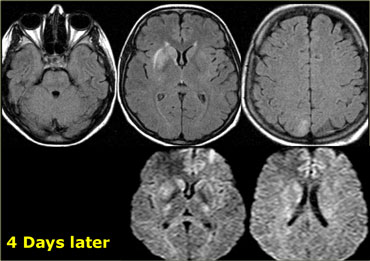

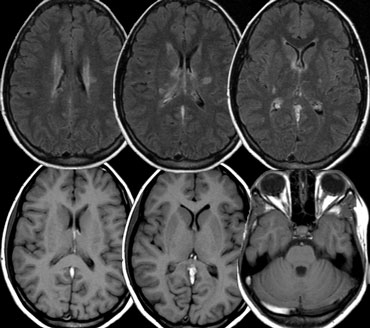

On the left images of a patient with reversible neurological symptoms.

The abnormalities are seen both in the posterior circulation as well as in the basal ganglia.

Continue.

Four days later most of the abnormalities have disappeared.

Cerebral Venous territory

There is great variation in the territories of venous drainage.

The illustrations on the left should be regarded as a rough guide.

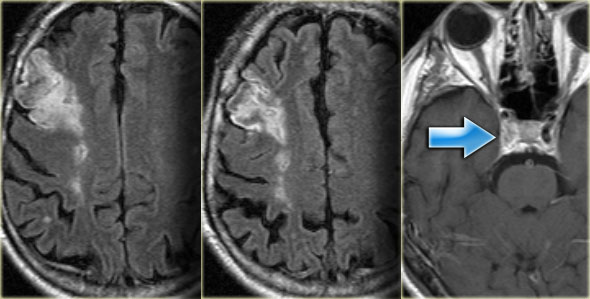

Cerebral venous thrombosis

Cerebral venous thrombosis results from occlusion of a venous sinus and/or cortical vein and usually is caused by a partial thrombus or an extrinsic compression that subsequently progresses to complete occlusion (7).

Dehydration, pregnancy, a hypercoagulable state and adjacent infection (eg, mastoiditis) are predisposing factors.

Cerebral venous thrombosis is an elusive diagnosis because of its nonspecific presentation.

It often presents with hemorrhagic infarction in areas atypical for arterial vascular distribution.

Imaging plays a key role in the diagnosis.

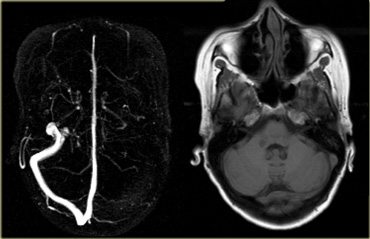

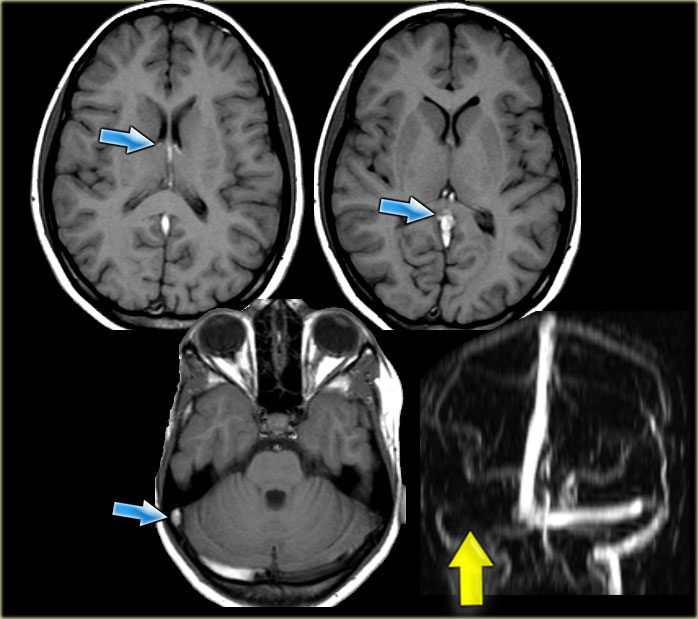

On the far left a MRA with non-visualization of the left transverse sinus.

Since the venous anatomy is variable, this can be due to absence of the transverse sinus or thrombosis.

The T1W-image on the right clearly demonstrates, that there is a transverse sinus on the left, so the MRA findings are due to thrombosis.

Continue with next images.

On the left the CT nicely demonstrates the dense thrombosed transverse sinus (yellow arrow).

The FLAIR image demonstrates the venous infarction in the temporal lobe.

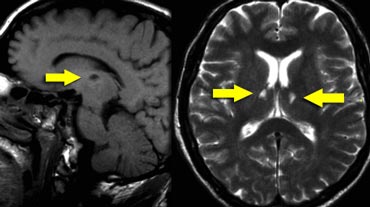

Thrombosis of deep cerebral veins

The clinical presentation of thrombosis of the deep cerebral venous system are severe dysfunction of the diencephalon, reflected by coma and disturbances of eye movements and pupillary reflexes.

Usually this results in a poor outcome.

However, partial syndromes without a decrease in the level of consciousness or brainstem signs exist, which may lead to initial misdiagnoses.

Deep cerebral venous system thrombosis is an underdiagnosed condition when symptoms are mild and should be suspected if the patient is a young woman, if the lesions are within the basal ganglia or thalamus and especially if they are bilateral.

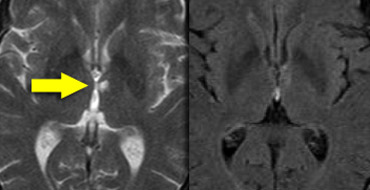

On the left images of a patient with deep cerebral vein thrombosis.

Notice the bilateral infarctions in the basal ganglia.

Continue.

There is absence of flow void in the internal cerebral veins, sinus rectus and right transverse sinus (blue arrows).

On the MRA the right transverse sinus is not visualized.

Charity

All the profits of the Radiology Assistant go to Medical Action Myanmar which is run by Dr. Nini Tun and Dr. Frank Smithuis sr, who is a professor at Oxford university and happens to be the brother of Robin Smithuis.

Click here to watch the video of Medical Action Myanmar and if you like the Radiology Assistant, please support Medical Action Myanmar with a small gift.