Common Liver Tumors

Richard Baron

Radiology department of the University of Chicago

Publicationdate

This article is based on a presentation given by Richard Baron and adapted for the Radiology Assistant by Robin Smithuis.

Richard Baron is Chair of Radiology at the University of Chicago and well known for his work on hepatobiliary diseases.

He has been president of the Society of Computed Body Tomography and Magnetic Resonance.

In Part I a basic concept is given on how to detect and characterize livermasses with CT.

In Part II the imaging features of the most common hepatic tumors are presented.

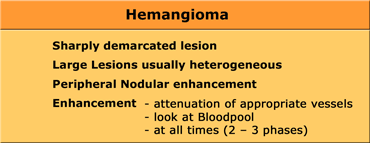

Hemangioma

Hemangioma is the most common benign liver tumor.

It is composed of multiple vascular channels lined by endothelial cells.

In 60% of cases more than one hemangioma is present.

The size varies from a few millimeters to more than 10 cm (giant hemangiomas).

Calcification is rare and seen in less than 10%, usually in the central scar of giant hemangioma.

CT will show hemangiomas as sharply defined masses with the same density as the vessels on NECT and CECT.

The enhancement pattern is characterized by sequential contrast opacification beginning at the periphery as one or more nodular areas of enhancement.

All these areas of enhancement must have the same density as the bloodpool.

This means that in the arterial phase the areas of enhancement must have almost the density of the aorta, while in the portal venous phase the enhancement must be of the same density as the portal vein.

Even on delayed images the density of a hemangioma must be of the same density as the vessels.

Finally most hemangiomas show complete fill in with contrast.

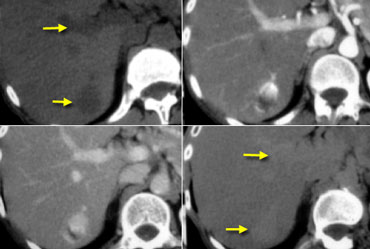

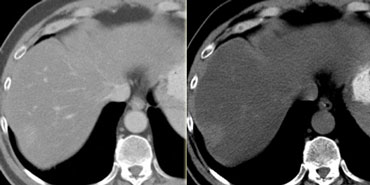

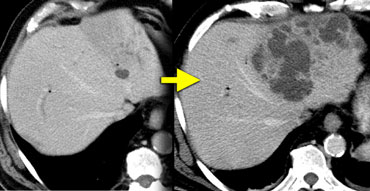

Flash filling hemangioma in unenhanced, arterial and portal venous phase. Notice it matches the bloodpool.

Flash filling hemangioma in unenhanced, arterial and portal venous phase. Notice it matches the bloodpool.

Small hemangiomas may show fast homogeneous enhancement ('flash filling').

Small HCC and hypervascular metastases may mimic small hemangiomas because they all show homogeneous enhancement in the arterial phase.

By looking at the other phases to see if the enhancing areas match the bloodpool, it is usually possible to differentiate these lesions.

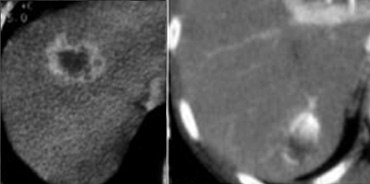

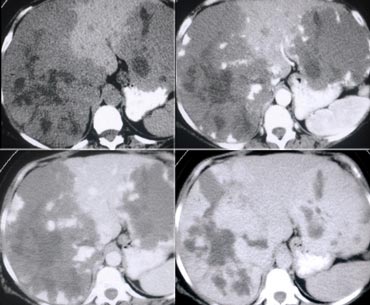

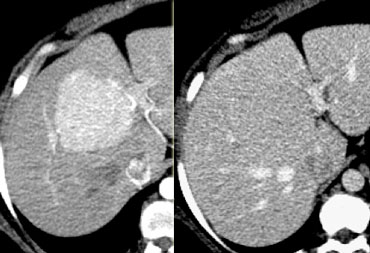

Giant hemangiomas with scar-tissue. Notice that the enhancement matches the bloodpool in all phases. Central scar is hypodens on NECT and stays hypodens.

Giant hemangiomas with scar-tissue. Notice that the enhancement matches the bloodpool in all phases. Central scar is hypodens on NECT and stays hypodens.

Large hemangiomas can have an atypical appearance.

Complete fill in is sometimes prevented by central fibrous scarring.

These lesions need to be differentiated from other lesions with a scar like FLC, FNH and Cholangiocarcinoma.

Again looking at the bloodpool will help you.

On the left two large hemangiomas.

Notice that the enhancing parts of the lesion follow the bloodpool in every phase, but centrally there is scar tissue that does not enhance.

Peripheral enhancement

The enhancement of a hemangioma starts peripheral .

It is nodular or globular and discontinuous.

Rim enhancement is continuous peripheral enhancement and is never hemangioma.

Rim enhancement is a feature of malignant lesions, especially metastases.

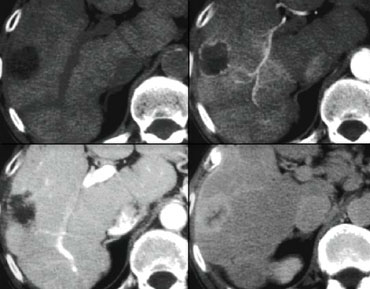

Progressive fill in

First look at the images on the left and describe what you see. Then continue.

The lesion definitely has some features of a hemangioma like nodular enhancement in the arterial phase and progressive fill in in the portal venous and equilibrium phase.

In the portal venous phase however, the enhancement is not as bright as the enhancement of the portal vein.

The conclusion must be, that this lesion does not match bloodpool in all phases, so it cannot be a hemangioma.

So progressive fill in is a non-specific feature, that can be seen in many other lesions like metastases or primary liver tumors like cholangiocarcinoma.

The delayed enhancement in this lesion is due to fibrotic tissue in a cholangiocarcinoma and is a specific feature of these tumors.

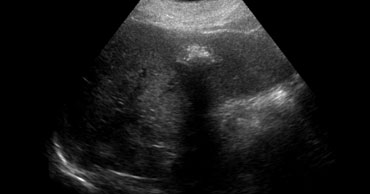

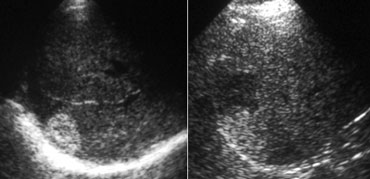

LEFT: Classic US appearance of a hemangioma.RIGHT: Also a hemangioma but now in a hyperechoic liver, so the lesion is relatively hypoechoic. Notice increased sound transmission.

LEFT: Classic US appearance of a hemangioma.RIGHT: Also a hemangioma but now in a hyperechoic liver, so the lesion is relatively hypoechoic. Notice increased sound transmission.

Ultrasound

Most hemangiomas are detected with US.

If you had to pick one word to characterize a hemangioma on US, you would probably say 'hyperechoic'.

You have to realize however, that this simply means that the lesion is hyperechoic to normal liver.

If the liver is hyperechoic due to steatosis, the hemangioma can appear hypoechoic (figure).

Another important feature of hemangiomas is the increased sound transmission.

This is because the lesion is made of these channels containing blood.

Differential diagnosis

Hemangiomas must be differentiated from other lesions that are hypervascular or lesions that show peripheral enhancement and progressive fill in.

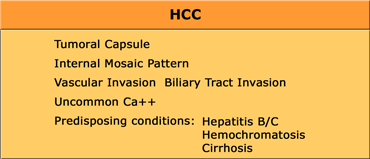

Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

HCC is the most frequent abdominal malignancy worldwide and is especially common in Asia and mediterrean countries.

HCC may be solitary, multifocal or diffusely infiltrating.

HCC consists of abnormal hepatocytes arranged in a typical trabecular pattern.

Larger HCC lesions typically have a mosaic appearance due to hemorrhage and fibrosis.

In patients with cirrhosis or with hepatitis B/C our major concern is HCC, since 85% of HCC occur in these patients.

If you take a cohort of patients with hepatitis C and you follow them for 10 years, 50% of them will have end stage liver disease and 25% will have HCC.

Early appearance of HCC

It is important to separate the early appearance from the late appearance of HCC.

Nowadays we encounter very small HCC's in patients, that we screen for HCC (figure).

These are small lesions that transiently enhance homogeneously.

You will only see them in the arterial phase.

Sometimes there is rim enhancement and you might mistake them for a hemangioma.

Always look how they present in the other phases and compare with the bloodpool and remember that rim enhancement is never hemangioma.

These early HCC's are very different from the large ones that we see in the non-cirrhotic patients.

Late appearance of HCC

HCC is a silent tumor, so if patients do not have cirrhosis or hepatitis C, you will discover them in a late stage.

They tend to be very large with a mozaic pattern, a capsule, hemorrhage, necrosis and fat evolution.

HCC becomes isodense or hypodense to liver in the portal venous phase due to fast wash-out.

On delayed images the capsule and sometimes septa demonstrate prolonged enhancement.

LEFT: Diffusely enhancing tumor thrombus in HCC with portal vein invasion.RIGHT: Tumor thrombus with vessels within the thrombus.

LEFT: Diffusely enhancing tumor thrombus in HCC with portal vein invasion.RIGHT: Tumor thrombus with vessels within the thrombus.

HCC and Portal Vein thrombosis

Many patients with cirrhosis have portal venous thrombosis and many patients with HCC have thrombosis.

These are two common findings and they can be coincidental.

It is very important to make the distinction between just thrombus and tumor thrombus.

First, if you have a malignant thrombus in the portal vein, it will always enhance and you'll see it best in arterial phase.

Secondly, if you have a malignant thrombus in the portal vein, it will increase the diameter of the vessel.

Sometimes a tumor thrombus may present with neovascularity within the thrombus (figure).

Differential diagnosis

Early HCC needs to be differentiated from other hypervascular lesions, that will be hyperdense in the arterial phase.

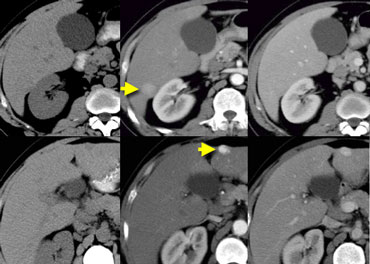

First look at the images on the left and look at the enhancement patterns.

Then continue.

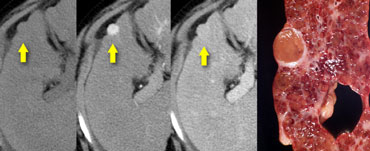

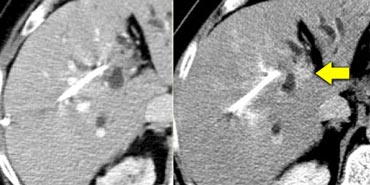

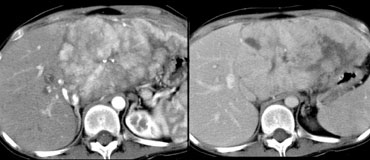

NECT, arterial and portal venous phase in a patient with Hepatitis C with two lesions in the liver (arrows).

NECT, arterial and portal venous phase in a patient with Hepatitis C with two lesions in the liver (arrows).

In the arterial phase we see two hypervascular lesions.

Now do not just concentrate on the images, where you see the lesions best.

You have to look at all the other images, because they give you the clue to the diagnosis.

The upper images show a lesion that is isodens to the liver on the NECT.

In the arterial phase there is enhancement, but not as dense as the bloodpool.

In the portal venous phase the lesion is again isodense to the surrounding liver parenchyma and you can't see it.

If you only had the portal venous phase you surely would miss this lesion.

The lower images show a lesion that is visible on all images.

You see it on the NECT and you could say it is hypodens compared to the liver.

Does this help you?

No, not in the least.

However if you look at the bloodpool, you will notice that on all phases it is as dense as the bloodpool.

So we have a HCC in the right lobe on the upper images and a hemangioma in the left lobe on the lower images.

The key is to look at all the phases.

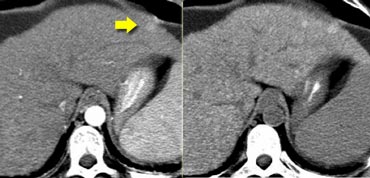

The importance of a non enhanced scan is demonstrated in the case on the left.

In the arterial phase we see a hyperdense structure in the lateral segment of the left lobe of the liver.

This looks like an enhancing nodule very suspective of early HCC.

However if we look at the NECT on the right, we'll notice, that it is not enhancement that we're looking at. It is just a siderotic iron containing hyperdense nodule.

They are very common and are seen in up to 50% of patients with cirrhosis.

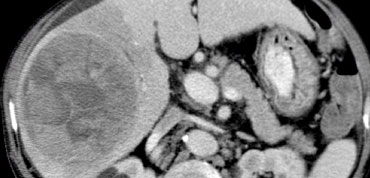

10% of HCC are hypodense compared to liver.

The imaging findings will be non-specific.

The case on the left proved to be HCC.

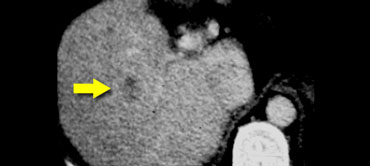

Hepatic Adenoma

Hepatocellular adenomas are large, well circumscribed encapsulated tumors.

They consist of sheets of hepatocytes without bile ducts or portal areas.

80% of adenomas are solitary and 20% are multiple.

Adenomas typically measure 8-15 cm and consist of sheets of well-differentiated hepatocytes.

Adenomas are prone to central necrosis and hemorrhage because the vascular supply is limited to the surface of the tumor.

The pathogenesis is believed to be related to a generalized vascular ectasia that develops due to exposure of the liver to oral contraceptives and related synthetic steroids.

In young woman using contraceptives an adenoma is the most frequent hepatic tumor.

CT will show most adenomas as a lesion with homogeneous enhancement in the late arterial phase, that will stay isodense to the liver in later phases.

Unfortunately, this homogeneous enhancement in the late arterial phase is not specific to adenomas, since small HCC's and hemangiomas as well as hypervascular metastases and FNH can demonstrate similar enhancement in the arterial phase.

Malignant lesions however have a tendency to loose their contrast faster than the surrounding liver, so they may become relatively hypodense in later phases.

The finding of hemorrhage as an area of high attenuation can be seen in as many as 40% of adenomas.

This is however also a feature of HCC and large hemangiomas.

Fat deposition within adenomas is identified on CT in only approximately 7% of patients and is better depicted on MRI.

Typically adenomas have well-defined borders and do not have lobulated contours.

A low-attenuation pseudocapsule can be seen in as many as 30% of patients.

This capsule will only show enhancement on delayed scans.

Coarse calcifications are seen in only 5% of patients.

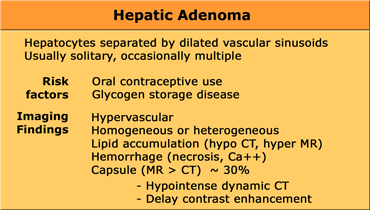

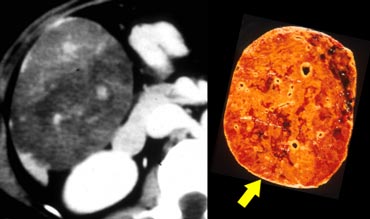

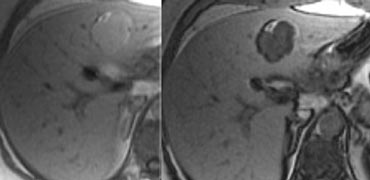

On the left an adenoma with fat deposition and a capsule.

MRI usually is more sensitive in detecting fat and hemorrhage.

Chemical-shift imaging showing loss of signal on out-of-phase images can confirm the presence of fat.

HCC is known to contain fat in as many as 40% of lesions, therefore the presence of fat does not help differentiate the lesions.

Adenomas may rupture and bleed, causing right upper quadrant pain.

The two most common liver lesions causing hepatic hemorrhage are HA and HCC.

Although adenomas are benign lesions, they can undergo malignant transformation to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Although malignant transformation is rare, for this reason, surgical resection is advocated in most patients with presumed adenomas.

Significant overlap is noted between the CT appearances of adenoma, HCC, FNH, and hypervascular metastases, making a definitive diagnosis based on CT imaging criteria alone difficult and often not possible.

Clinical correlation in such cases is most helpful.

In otherwise healthy young women using oral contraceptives, adenoma is favored.

Patients with glycogen storage disease, hemochromatosis, acromegaly, or males on anabolic steroids also are more prone to developing hepatic adenomas.

A history of cirrhosis and high AFP levels favor HCC.

A history of a primary hypervascular tumor favors metastases.

As a result of the risk of intraperitoneal hemorrhage and the rare occurrence of malignant transformation to HCC, surgical resection has been advocated in most patients with presumed HA.

The risk of significant bleeding from the tumor is as high as 30%.

The exact risk of malignant transformation is unknown.

Some advocate surgical resection only when tumors are larger than 5 cm or when AFP levels are elevated, since these two findings are associated with higher risk of malignancy.

The value of percutaneous fine needle biopsy for the diagnosis of HA is controversial for two reasons.

First, histologic studies may lead to misdiagnosis when differentiating HA from FNH.

In addition, a considerable risk of hemorrhage exists when biopsy is performed on these hypervascular tumors.

Adenomas may diminish after oral contraceptives are discontinued, but this does not lower the risk of malignant transformation.

When a definitive diagnosis of FNH can be made using imaging studies, surgery can be avoided and lesions can be observed safely using radiologic studies.

However, if HA or HCC remains in the differential diagnosis, surgery usually is indicated.

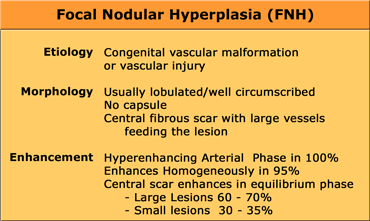

Focal Nodular Hyperplasia (FNH)

FNH is the second most common tumor of the liver.

FNH is not a true neoplasm. It is believed to represent a hyperplastic response to increased blood flow in an intrahepatic arteriovenous malformation.

All the normal constituents of the liver are present but in an abnormally organized pattern.

US will show a FNH as a non specific ill-defined lesion.

The central scar may be detected as a hyperechoic area, but often cannot be differentiated.

With color doppler sometimes the vessels can be seen within the scar.

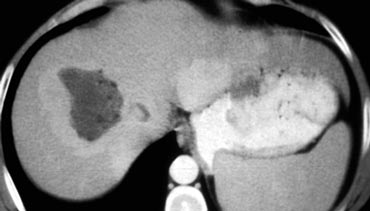

CT will show FNH as a vascular tumor, that will be hyperdens in the arterial phase, except for the central scar.

On the left a typical FNH with a central scar that is hypodens in the portal venous phase and hyperdens in the equilibrium phase.

MRI will show a hypointense central scar on T1-weighted images.

On T2-weighted images the scar appears as hyperintense in 80% of patients, which is very typical.

However in 20% of patients the scar is hypointense.

Gadolineum enhanced MRI will reveal similar enhancement patterns as on CECT.

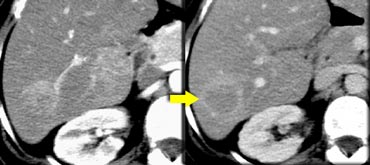

FNH seen as hypervascular lesion in the late arterial phase and isodense to normal liver in the portal venous phase. No scar was seen.

FNH seen as hypervascular lesion in the late arterial phase and isodense to normal liver in the portal venous phase. No scar was seen.

The diagnosis of FNH is based on the demonstration of a central scar and a homogeneous enhancement.

However, a typical central scar may not be visible in as many as 20% of patients (figure).

Moreover a central scar may be found in some patients with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatic adenoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

The key to the diagnosis in the lesion on the left is the fact that it is isoattenuating to normal liver in the portal venous phase and stays that way without a wash out on the delayed phase (not shown).

This could also be an adenoma, but HCC would be unlikely because they show a fast wash out.

If you look at the images on the left and just would consider the T2W-images, what could be the cause of the central area of high signal?

The most common cause would be central necrosis in a tumor.

However if you look at the delayed phase, you will notice that this area enhances.

So this is fibrotic tissue and the diagnosis is FNH.

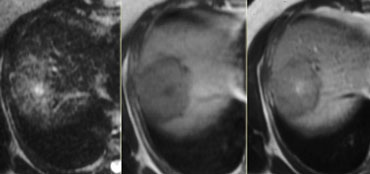

Fibrolamellar carcinoma (FLC) has a dark scar on T2WI and FNH has a brigth scar on T2WI in 80% of the cases.

This means that at times the differential between FNH and FLC will not be possible.

Fibrolamellar carcinoma (FLC)

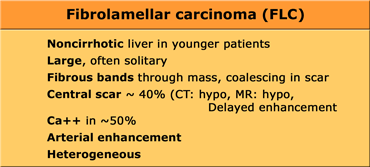

FLC is an uncommon malignant hepatocellular tumor, but less aggressive than HCC.

FLC characteristically manifests as a 10-20 cm large hepatic mass in adolescents or young adults.

The typical risk factors for HCC such as cirrhosis, elevated alphafetoprotein, viral hepatitis, alcohol abuse are absent.

FLC characteristically appears as a lobulated heterogeneous mass with a central scar in an otherwise normal liver. Calcifications occur in 30-60% of fibrolamellar tumors.

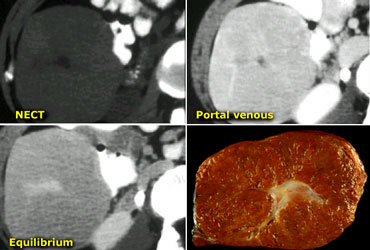

LEFT: FLC in late arterial phase: central calcification and heterogenous enhancement in a lamellar pattern. RIGHT: venous phase with hypodense central scar.

LEFT: FLC in late arterial phase: central calcification and heterogenous enhancement in a lamellar pattern. RIGHT: venous phase with hypodense central scar.

Imaging features of FLC overlap with those of other scar-producing lesions including FNH, HCC, Hemangioma and Cholangiocarcinoma.

FNH, in particular, may simulate FLC, since both have similar demographic and clinical characteristics.

In contrast to FNH the central scar in FLC will usually be hypointense on T2WI and will less often show delayed enhancement.

While FNH is always very homogeneous, FLC is usually heterogeneous following contrast administration.

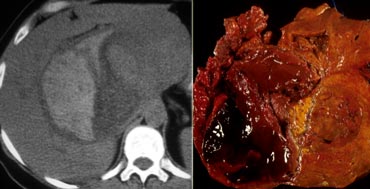

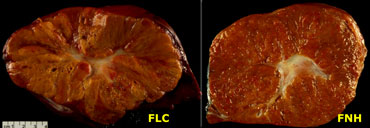

On the left pathologic specimens of FLC and FNH.

At first glance they look very similar.

However when you look carefully you will notice the lamellar and heterogenous structure of FLC compared to the homogeneous appearance of FNH.

On non enhanced images a FLC usually presents as a big mass with central calcifications.

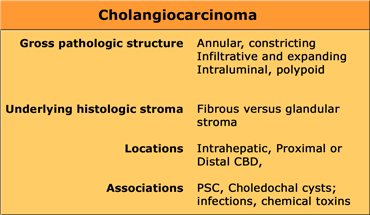

Cholangiocarcinoma

Cholangiocarcinoma usually presents as a mass of 5-20cm. In 65% there are satellite nodules and in some cases punctate calcifications are seen.

The diagnosis of a cholangiocarcinoma is often difficult to make for a radiologist and even a pathologist.

That is because cholangiocarcinoma has a varied morphology and histology.

It can be a constricting or an expanding lesion, because it can have a fibrous or a glandular stroma.

It can be located anywhere in the intrahepatic bile ducts or common bile duct.

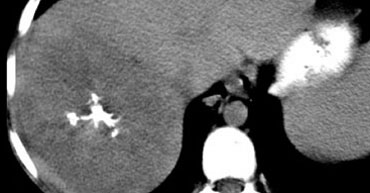

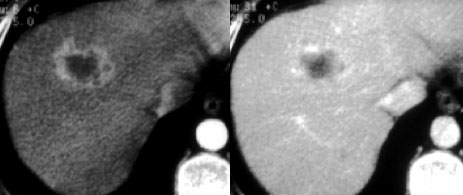

First look at the images on the left and try to find good descriptive terms for what you see. Then continue.

The lesion on the left has the folowing characteristics:

- The lesion is hypodens in the arterial and portal venous phase with some peripheral enhancement.

- The lesion is hyperdense in the equilibrium phase indicating dens fibrous tissue.

- The lesion causes retraction of the liver capsule

The finding of an infiltrating mass with capsular retraction and delayed persistent enhancement is very typical for a cholangiocarcinoma.

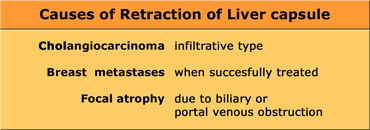

Infiltrative cholangiocarcinoma does not cause mass effect, because when the stroma matures, the fibrous tissue will contract and cause retraction of the liver capsule.

There are not many tumors that cause retraction of the liver capsule, since most tumors will bulge.

The most common tumor that causes retraction besides cholangiocarcinoma is metastatic breast cancer.

This will give a pseudo-cirrhosis appearance.

Another cause of local retraction is atrophy due to biliary obstruction or chronic portal venous obstruction.

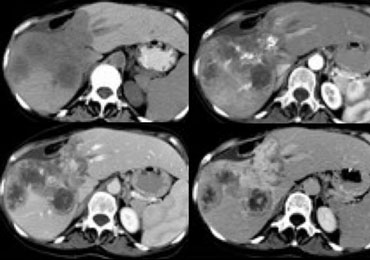

The case on the left demonstrates how difficult the detection of ta cholangiocarcinoma can be.

Only on the delayed images at 8-10 minutes after contrast injection a relative hyperdense lesion is seen. This is the fibrous component of the tumor.

Some cholangiocarcinomas have a glandular stroma.

Hepatic Metastases

The liver is the most common site of metastases.

The most common organs of origin are: colon, stomach, pancreas, breast and lung.

Most liver metastases are multiple, involving both lobes in 77% of patients and only in 10% of cases there is a solitary metastasis.

Hypovascular metastases are the most common and occur in GI tract, lung, breast and head/neck tumors.

They are detected as hypodense lesions in the late portal venous phase.

In this phase the attenuation of the normal liver parenchyma increases, revealing the relatively hypoattenuating metastases, sometimes with peripheral enhancement.

The rim enhancement that occurs represents viable tumor peripherally, which appears against a less viable or necrotic center (figure).

Hypervascular metastases are less common and are seen in renal cell carcinoma, insulinomas, carcinoid, sarcomas, melanoma and breast cancer.

They are best seen in the late arterial phase at 35 sec after contrast injection.

Although breast cancer metastases can be hypervascular, it was shown that routine use of adding arterial phase imaging, did not show any advantage.

Calcified liver metastases are uncommon. Calcification can be seen in metastases of colon, stomach, breast, endocrine pancreatic ca, leiomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma and melanoma.

When calcified liver metastases are revealed by CT in a patient with unknown primary tumor, colon cancer will be the most likely cause.

Cystic liver metastases are seen in mucinous ovarian ca, colon ca, sarcoma, melanoma, lung ca and carcinoid tumor.

On MRI metastases are usually hypointense on T1WI and hyperintense on T2WI.

Peritumoral edema makes lesions appear larger on T2WI and is very suggestive of a malignant mass.

On dynamic contrast-enhanced MRi the characteristics of metastases are the same as for CECT.

Ultrasound findings

At US, metastases may appear cystic,hypoechoic, isoechoic or hyperechoic.

Bull's eye or target lesions is a common presentation of metastases. In these metastases the halo is most probably related to a combination of compressed normal hepatic parenchyma around the mass and a zone of cancer cell proliferation.

This pattern suggests aggressive behavior and is seen in bronchogenic, breast and colon carcinoma, .

However, this pattern is not specific for metastases as it can also be seen in primary malignant liver neoplasms (eg, HCC) and benign liver neoplasms (eg, adenoma in glycogen storage disease).

A similar appearance has been described with liver abscesses.

Calcified metastases may shadow when they are densely echogenic (figure). This pattern is commonly seen in colorectal cancer.

Differential diagnosis

Metastases can look like almost any lesion that occurs in the liver.

Hypervascular metastases have to be differentiated from other hypervascular tumors that can be multifocal like hemangiomas, FNH, adenoma and HCC.

Hypovascular metastases have to be differentiated from focal fatty infiltration, abscesses, atypical hypovascular HCC and cholangiocarcinoma.

Metastases in fatty liver

Focal fatty sparing in a diffusely fatty liver or foci of focal fatty infiltration can simulate metastases.

However on nonenhanced scans these regions of fat variation tend to be nonspherical and geographic, with no mass effect or distortion of the local vessels.

On the other hand a fatty liver can also obscure metastases.

On a contrast enhanced CT hypovascular lesions can be obscured if the liver itself is lower in density due to fat deposition. On a NECT these lesions usually are better depicted (figure).

If a patient is known to have a fatty liver, it is better to do an MRI or ultrasound for the detection of livermetastases.

On the left a patient with fatty infiltration of large parts of the liver.

No metastases were seen, but on an ultrasound of the same region multiple metastases were detected.

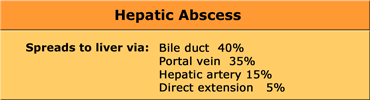

Liver abces

The presentation of liver abcesses is very much dependend on the way the bacteria have entered the liver.

There are four routes for bacteria to get into the liver.

The common route is through the portal vein as a result of abdominal infection.

The bacteria enter through the slow flow portal system and they are layered within the vessel.

The bacteria will fall down into the dependent portion of the right lobe.

In sepsis the spread will be via the arterial system as in patients with endocarditis and there will be multiple abscesses spread out through the periphery of the liver.

The biliary route is often the result of biliary manipulation as in ERCP. It is usually central in location and then spreads out.

Finally there is a direct route as in penetrating injury or direct spread of cholecystitis into the liver.

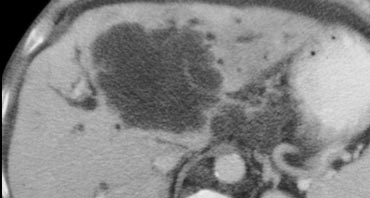

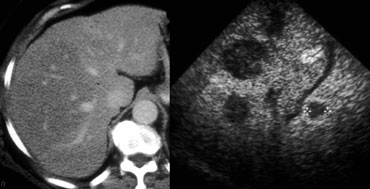

First look at the images on the left and try to find good descriptive terms for what you see. Then continue.

If you would describe the image on the left, you would use terms as:

- Hypovascular lesions

- Low density, so it may be cystic i.e fluid containing.

- Clustered or satelite lesions. These lesions are multiple, but not spread out through the liver.

- Although it is difficult to see, there is also portal venous thrombosis on the left.

So these findings suggest liverabscesses especially because it's clustered.

Only when you have a population with livertransplants, bilomas in an infarcted area would look the same.

If it wasn't clustered than any cystic tumor could look like this.

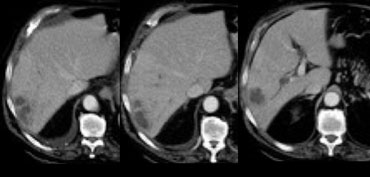

It is very important to make the diagnosis of liver absces because it is a benign disease that kills and the radiologist may be the first to raise the suspicion.

Whenever you see a small cyst-like lesion in a patient who recently underwent an ERCP, be very carefull to assume it is just a simple cyst.

Biliary abscesses start small but can progress rapidly.

The figure on the left shows such a case.

Within 3 weeks the small lesion in the left liver lobe progressed to this huge abces.

So any cystic structure near the biliary tract in a patient, who recently has undergone a biliary procedure, is suspicious of a liver abces.