Practical approach to Acute Abdomen

Adriaan van Breda Vriesman and Robin Smithuis

Radiology department of the Rijnland Hospital, Leiderdorp, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

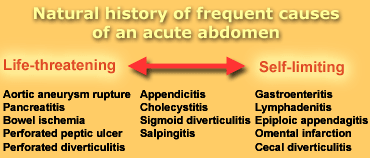

The 'acute abdomen' is a clinical condition characterized by severe abdominal pain, requiring the clinician to make an urgent therapeutic decision.

This may be challenging, because the differential diagnosis of an acute abdomen includes a wide spectrum of disorders, ranging from life-threatening diseases to benign self-limiting conditions (Table 1).

Indicated management may vary from emergency surgery to reassurance of the patient and misdiagnosis may easily result in delayed necessary treatment or unnecessary surgery.

Sonography and CT enable an accurate and rapid triage of patients with an acute abdomen.

We present practical guidelines on the radiological approach of these patients.

Interactive cases are presented in the menubar to test your knowledge.

Radiological strategy

Before you perform an examination, obtain relevant information from the referring clinician.

Don't let the clinician simply 'order' a sonogram or CT, but discuss the patient's age and posture, laboratory results and the number one clinical diagnosis and differential diagnosis.

Based on that information and your own degree of confidence with the modalities decide for yourself whether to perform sonography or CT.

Sonography has the advantage of close patient contact, enabling assesment of the spot of maximum tenderness and the severity of illness without ionizing radiation.

In general the diagnostic accuracy of CT is higher than sonography.

In patients with inconclusive US-results, CT can serve as an adjunct to sonography, and vice versa.

We advocate the following two-step radiological approach of an acute abdomen.

1. Confirm or exclude the most common disease

2. Screen for general signs of pathology

You have to be familiar with all the diagnoses listed in Table 1 to be able to recognize them.

Clinics, laboratory, and plain abdominal film

The clinical presentation of patients with an acute abdomen is often nonspecific.

Both surgical and nonsurgical diseases may present with a similar clinical history and symptoms.

Laboratory findings (leucocyte count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP) are equally nonconclusive.

Findings may be normal in patients who need emergency surgery (such as appendicitis) and may be abnormal in patients without a surgical disease (like salpingitis).

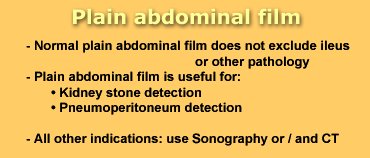

A plain abdominal film has a limited value in the evaluation of abdominal pain.

A normal film does not exclude an ileus or other pathology and may falsely reassure the clinician.

LEFT: Plain abdominal film in a patient with an acute abdomen, showing no abnormalities. RIGHT: Subsequent CT shows distended small bowel loops (arrowheads) that are not seen on plain abdominal film because they are filled with fluid only and do not contain intraluminal air.

LEFT: Plain abdominal film in a patient with an acute abdomen, showing no abnormalities. RIGHT: Subsequent CT shows distended small bowel loops (arrowheads) that are not seen on plain abdominal film because they are filled with fluid only and do not contain intraluminal air.

An ileus may not be appreciated on a plain abdominal film if bowel loops are filled with fluid only without intraluminal air (figure).

Alternatively if a plain abdominal film does indicate an ileus than sonography or CT are usually needed to identify its cause.

Thus, a plain abdominal film is seldomly useful, with the exception of detection of kidney stones or a pneumoperitoneum.

For all other indications use sonography or CT.

Confirm or exclude the most common disease

Many disorders may cause an acute abdomen, but fortunately only a few of these are common and clinically important.

Focus on confirming or excluding these frequent disorders:

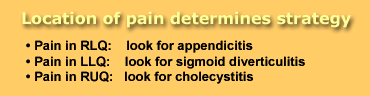

RLQ : Appendicitis

Pain in the RLQ, regardless of any other symptom or laboratory results, should be considered to be appendicitis until proven otherwise.

If you are unable to find the appendix you cannot rule out the diagnosis of appendicitis unless a good alternative diagnosis is found.

If you do not find the appendix and there is no altermative diagnosis call the results of the examination indeterminate. Do not call it:' no appendicitis'.

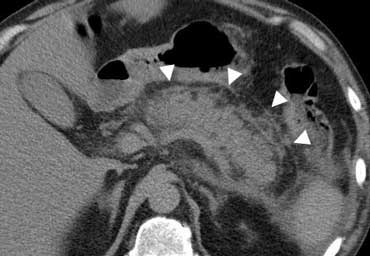

Normal appendix : Longitudinal (A) sonogram depicts a blind-ending tubular structure (arrowheads) with 'gut-signature', with a maximum outer diameter of 6 mm, with noninflamed surrounding fat. On an axial view (B) the appendix can be compressed crossing the iliac vessels.

Normal appendix : Longitudinal (A) sonogram depicts a blind-ending tubular structure (arrowheads) with 'gut-signature', with a maximum outer diameter of 6 mm, with noninflamed surrounding fat. On an axial view (B) the appendix can be compressed crossing the iliac vessels.

Normal Appendix.

Your first task is to identify the appendix.

At sonography and CT the appendix is seen as a blind-ending nonperistaltic tubular structure arising from the base of the cecum.

Do not mistake a small bowel loop for the appendix.

Secondly determine if the appendix is normal or inflamed.

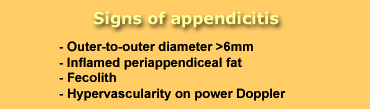

The outer-to-outer diameter of the appendix is the most important imaging criterium.

Although an overlap of appendiceal diameters in normal and inflamed appendices can incidentally be found, a threshold value of 6-7 mm is generally used.

Normal appendix: CT shows an air-containing non-distended appendix (arrowheads), with homogeneous low-density periappendiceal fat.

Normal appendix: CT shows an air-containing non-distended appendix (arrowheads), with homogeneous low-density periappendiceal fat.

A normal appendix has a maximum diameter of 6 mm, is surrounded by homogeneous non-inflamed fat, is compressible and often contains intraluminal gas.

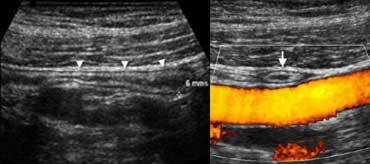

Inflamed appendix at sonography. Longitudinal (A) and transverse (B) cross-section show a distended noncompressible appendix, surrounded bij hyperechoic inflamed fat (arrowheads).

Inflamed appendix at sonography. Longitudinal (A) and transverse (B) cross-section show a distended noncompressible appendix, surrounded bij hyperechoic inflamed fat (arrowheads).

Inflamed Appendix

An inflamed appendix has a diameter larger than 6 mm, and is usually surrounded by inflamed fat. The presence of a fecolith or hypervascularity on power Doppler strongly supports inflammation.

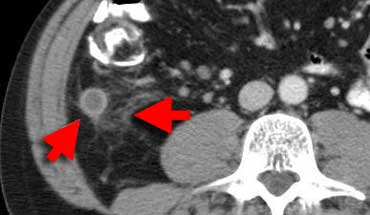

Inflamed appendix at CT. The appendix (arrows) is fluid-filled and distended with periappendiceal fat-stranding.

Inflamed appendix at CT. The appendix (arrows) is fluid-filled and distended with periappendiceal fat-stranding.

CT depicts an inflamed appendix as a fluid-filled blind-ending tubular structure surrounded by fat-stranding.

In the case on the left a hyper-attenuating wall is seen on the enhanced CT.

In patients who lack intra-abdominal fat the use of iv. contrast can be helpfull in depicting the inflamed appendix.

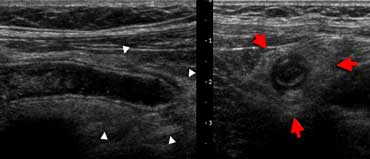

Sigmoid diverticulitis at sonography. A hypoechoic thickened diverticulum is surrounded by hyperechoic inflamed fat (arrows).

Sigmoid diverticulitis at sonography. A hypoechoic thickened diverticulum is surrounded by hyperechoic inflamed fat (arrows).

LLQ : Diverticulitis

If the pain is located in the LLQ your main concern is sigmoid diverticulitis.

In diverticulitis sonography and CT show diverticulosis with segmental colonic wall thickening and inflammatory changes in the

fat surrounding a diverticulum.

Uncomplicated sigmoid diverticulitis. Fat stranding and focal thickening of the colonic wall in an area with diverticula. No abscess formation.

Uncomplicated sigmoid diverticulitis. Fat stranding and focal thickening of the colonic wall in an area with diverticula. No abscess formation.

Complications of diverticulitis such as abscess formation or perforation, can best be excluded with CT.

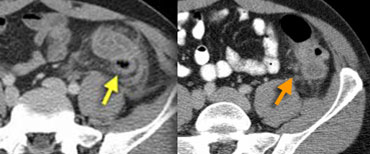

LEFT: Sigmoid diverticulitis. Diverticulum (arrow) is surrounded by hyperattenuating fat. The sigmoid wall is thickened. RIGHT: Sigmoid carcinoma with limited fat stranding.

LEFT: Sigmoid diverticulitis. Diverticulum (arrow) is surrounded by hyperattenuating fat. The sigmoid wall is thickened. RIGHT: Sigmoid carcinoma with limited fat stranding.

An important pitfall is colon cancer, which may present with similar imaging features, especially when the colon cancer is surrounded by fat stranding due to invasive groth, desmoplastic reaction or inflammation.

Frequently it is not possible to reliably distinguish diverticulitis from colon cancer and therefore we routinely include colon cancer in the differential diagnosis of sigmoid diverticulitis.

RUQ : Cholecystitis

Cholecystitis occurs when a calculus obstructs the cystic duct. The trapped bile causes inflammation of the gallbladder wall.

As gallstones are often occult on CT, sonography is the preferred imaging method for the evaluation of cholecystitis, also allowing assesment of the compressiblity of the gallbladder.

The diagnosis of a hydropic galbladder is solely made on the non-compressability of the galbladder. Do not rely on measurements. Some galbladders happen to be small and others are large.

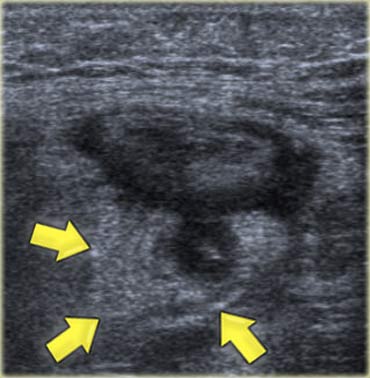

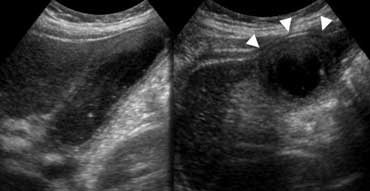

Longitudinal and transverse US show thickened gallbladder wall. The gallbladder is noncompressible ('hydropic') and causes an impression in the anterior abdominal wall (arrowheads).

Longitudinal and transverse US show thickened gallbladder wall. The gallbladder is noncompressible ('hydropic') and causes an impression in the anterior abdominal wall (arrowheads).

The imaging appearance of cholecystis consists of an enlarged hydropic (meaning non-compressible) gallbladder with a thickened wall in the region of maximum tenderness (the so-called 'Murphy sign')

Cholecystitis at CT. The gallbladder is enlarged with edematous thickening of its wall (arrowhead), and some regional fat-stranding can be found.

Cholecystitis at CT. The gallbladder is enlarged with edematous thickening of its wall (arrowhead), and some regional fat-stranding can be found.

The inflamed gallbladder usually contains stones or sludge, whereas the obstructing calculus itself may or may not be identified because it is located deep within the galbladder neck or cystic duct.

The gallbladder may be surrounded by inflamed fat, but on sonography this frequently is not seen, while CT sometimes does show fat-stranding.

Potential pitfalls are pancreatitis, hepatitis or right-sided heart failure, which all may lead to thickening of the gallbladder wall without cholecystitis.

Therefore be certain that hydropic obstruction of the gallbladder is present before assigning the diagnosis of cholecystitis.

Pain in LUQ

An acute abdomen with LUQ pain is rare.

Its most common cause is gastric pathology in which radiological imaging plays a minor role.

Screen for general signs of pathology

After excluding these frequent disorders, search for signs of any other pathology, by systematically screening the whole abdomen.

Look for inflamed fat, bowel wall thickening, ileus, ascites and free air.

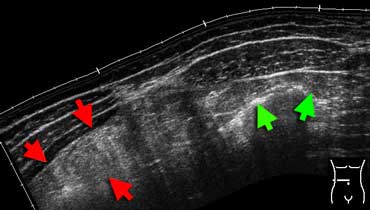

Inflamed fat at sonography. Extended-view of the ventral abdomen depicting an area of hyperechoic noncompressible inflamed fat in the omentum (red arrows). Compare this to the echogenicity of normal abdominal or subcutaneous fat (green arrows). This patient had an omental infarction.

Inflamed fat at sonography. Extended-view of the ventral abdomen depicting an area of hyperechoic noncompressible inflamed fat in the omentum (red arrows). Compare this to the echogenicity of normal abdominal or subcutaneous fat (green arrows). This patient had an omental infarction.

Inflamed fat

Inflamed fat is hyperechoic, space occupying and noncompressible at sonography.

Same patient as above. Unenhanced CT depicts an area of fatty tissue with slightly increased density (arrowheads), in the right-upper quadrant. Compare this to normal low-density subcutaneous fat. Diagnosis: omental infarction.

Same patient as above. Unenhanced CT depicts an area of fatty tissue with slightly increased density (arrowheads), in the right-upper quadrant. Compare this to normal low-density subcutaneous fat. Diagnosis: omental infarction.

Inflamed fat is shown as fat-stranding at CT. Inflamed fat usefully points out where and what the problem is.

As a rule, the organ or structure in the centre or nearest to the inflamed fat is the cause of the inflammation.

Bowel wall thickening

Thickening of bowel wall indicates inflammation or tumor, and has an extensive differential diagnosis.

Thickening of small bowel loops usually indicates regional inflammation, as small bowel tumors (carcinoid, lymphoma, GIST) are relatively infrequent.

In patients with local colonic wall thickening a carcinoma is a prime concern.

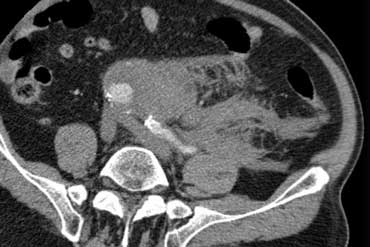

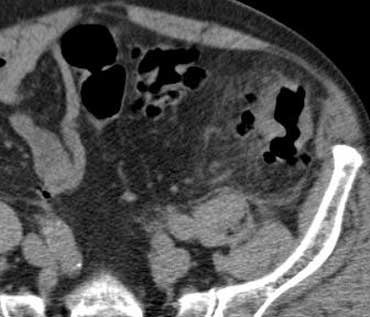

Obstructive ileus. CT depicts distended small bowel loops, but part of the small bowel and the whole colon is nondistended. Therefore this must be an obstructive small bowel ileus, and in this case its cause can easily be identified: intussusception (arrowhead).

Obstructive ileus. CT depicts distended small bowel loops, but part of the small bowel and the whole colon is nondistended. Therefore this must be an obstructive small bowel ileus, and in this case its cause can easily be identified: intussusception (arrowhead).

Ileus

Pathologic distention of bowel loops may be caused by obstruction or paralysis.

Firstly determine which parts of the gut are affected: small bowel, large bowel, or both.

Look for normal nondistended bowel loops, which, if present, strongly suggest an obstructive cause for the ileus.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) accounts for approximately 4% of all patients presenting with an acute abdomen.

The diagnosis of SBO is made when you see dilated small bowel and collapsed small bowel loops.

If obstruction is present, try to identify its cause and location (adhesion, tumor, volvulus, intussusception, inguinal hernia).

Adhesions account for 60-80% of all cases and are the likely cause when a smooth transition from dilated to collapsed small-bowel loops is noted.

The 'Small Bowel Feces Sign' (SBFS) is a very useful sign as it is seen at the zone of transition thus facilitating identification of the cause of the obstruction.

The SBFS has been defined as gas and particulate material within a dilated small-bowel loop that simulates the appearance of feces.

Scroll through the images on the left to see the small bowel feces sign indicating the site of obstruction.

Alternatively, an ileus without any normal bowel loops strongly suggests a paralytic cause.

This is usually a response to general peritonitis, wich may have many possible causes of the inflammation.

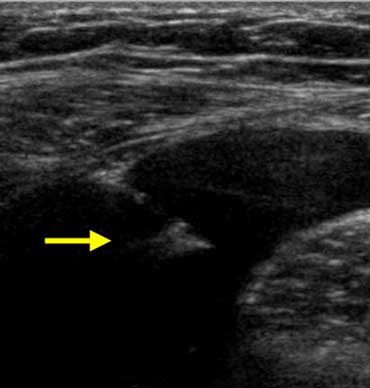

Clinically appendicitis. US only showed a little bit of ascites. A diagnostic puncture (arrow marks needletip) revealed blood. In a woman this finding is very suspicious of an EUG.

Clinically appendicitis. US only showed a little bit of ascites. A diagnostic puncture (arrow marks needletip) revealed blood. In a woman this finding is very suspicious of an EUG.

Ascites

Asymptomatic volunteers do not have a detectable amount of free intraperitoneal fluid, with the exception of an incidental drop of fluid in Douglas in fertile women.

The presence of ascites is a nonspecific sign of abdominal pathology, indicating that 'something is wrong'.

You may want to perform a US-guided diagnostic puncture of the ascites, in order to investigate whether it is sterile reactive fluid, pus, blood, urine, or bile.

Intraperitoneal air in a patient suspected of having appendicitis. Air better seen on images with lungsetting on the right.

Intraperitoneal air in a patient suspected of having appendicitis. Air better seen on images with lungsetting on the right.

Free air

The presence of free intraperitoneal air is proof of bowel perforation, and indicates a surgical emergency.

A pneumoperitoneum has only two frequent causes:

- Perforation of a gastric ulcer

- Perforation of colonic diverticulitis

Free air is usually not seen in perforated appendicitis).

Always examine the images in lungsetting for better detection of free intraabdominal air (figure).

Differential diagnosis

A complete list of all possible causes of an acute abdomen is of little use in daily practice, therefore we just provide some imaging examples of several frequent causes of acute abdominal pain

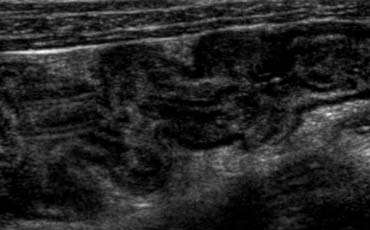

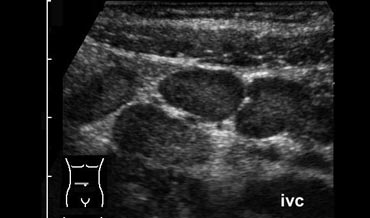

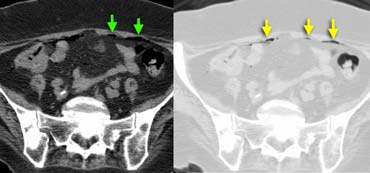

Mesenteric lymphadenitis.

Mesenteric lymphadenitis is a common mimicker of appendicitis.

It is the second most common cause of right lower quadrant pain after appendicitis.

It is defined as a benign self-limiting inflammation of right-sided mesenteric lymph nodes without an identifiable underlying inflammatory process, occurring more often in children than in adults..

This diagnosis can only be made confidently when a normal appendix is found, because adenopathy also frequently occurs with appendicitis.

Key finding: Lymphadenopathy with a normal appendix and normal mesenteric fat.

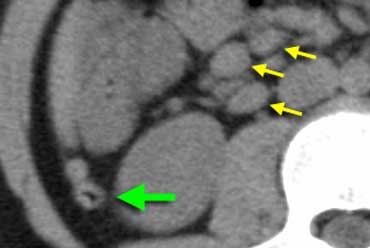

On the left a CT of mesenteric lymphadenitis in a child suspected of appendicitis.

US typically shows submucosal wall thickening (arrowheads) of the terminal ileum and cecum without inflammation of the surrounding fat.

US typically shows submucosal wall thickening (arrowheads) of the terminal ileum and cecum without inflammation of the surrounding fat.

Bacterial ileocecitis

Infectious enterocolitis may cause mild symptoms resembling a common viral gastroenteritis, but it may also clinically present with features indistinguishable from appendicitis especially in bacterial ileocecitis, caused by Yersinia, Campylobacter, or Salmonella.

Key finding: ileocecal wall thickening without inflamed fat, adenopathy, normal appendix

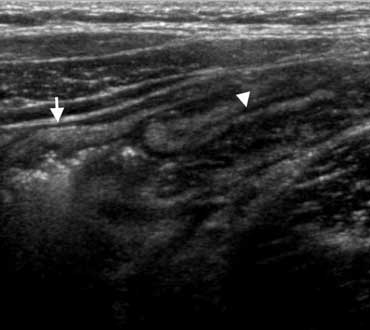

Right-sided diverticulitis

Right-sided colonic diverticulitis may clinically mimic appendicitis or cholecystitis, though the patient's history is generally more protracted.

In contrast to sigmoid diverticula, right-sided colonic diverticula are usually true diverticula, that is, outpouchings of the colonic wall containing all layers of the wall.

This may possibly explain the essentially benign self- limiting character of right-sided diverticulitis.

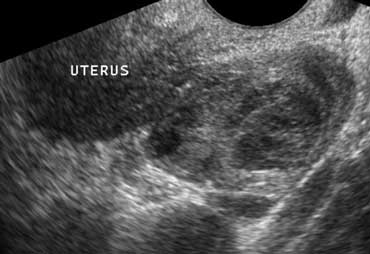

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Pelvic inflammatory disease is a common mimicker of both of appendicitis and diverticulitis.

Transvaginal sonography depicts an inhomogeneous enlarged inflamed ovary.

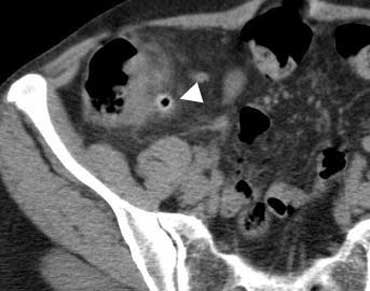

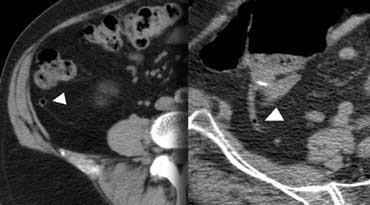

CT characteristic of epiploic appendagitis with a right-sided fatty mass surrounded by a hyperattenuating ring.

CT characteristic of epiploic appendagitis with a right-sided fatty mass surrounded by a hyperattenuating ring.

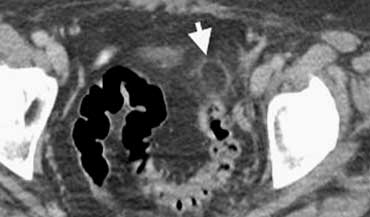

Epiploic appendagitis.

Epiploic appendages are small adipose protrusions from the serosal surface of the colon.

An epiploic appendage may undergo torsion and secondary inflammation causing focal abdominal pain that simulates appendicitis when located in the right lower quadrant or diverticulitis when located in the left lower quadrant.

The characteristic ring-sign corresponds to inflamed visceral peritoneal lining surrounding an infarcted fatty epiploic appendage.

Left sided epiploic appendagitis in patient clinically suspected of having a diverticulitis.Characteristic hyperattenuating ring sign.

Left sided epiploic appendagitis in patient clinically suspected of having a diverticulitis.Characteristic hyperattenuating ring sign.

Epiploic appendagitis has been reported in approximately 1% of patients clinically suspected of having appendicitis.

It is very important to make a positive diagnosis of this characteristic entity since epiploic appendagitis is a self-limiting disease.

Both US and CT will depict an inflamed fatty mass adjacent to the colon.

Key finding: inflamed fatty mass adjacent to the colon with characteristic ring sign.

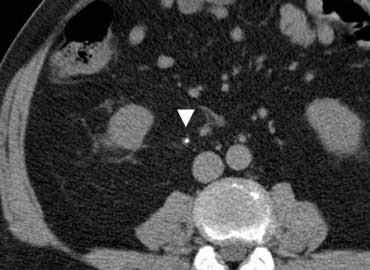

Urolithiasis

Urolithiasis often causes flank pain, but an ureteral stone (arrowhead) may occasionally present with clinical signs simulating appendicitis, cholecystitis or diverticulitis.

Appendicitis on the other hand may cause hematuria, pyuria and albuminuria in up to 25% of patients because of ureteral inflammation from an adjacent inflamed appendix.

Ruptured Aneurysm

Most abdominal aortic aneurysms rupture into the left retroperitoneum (4).

Clinically this may simulate sigmoid diverticulitis or renal colic due to impingement of the hematoma on adjacent structures.

However most patient will present with the classic triad of hypotension, a pulsating mass and

back pain.

Continuous leakage will lead to rupture into the peritoneal cavity and eventually death.

Sonography is a quick and convenient modality, but it is much less sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of aneurysmal rupture than CT.

The absence of sonographic evidence of rupture does not rule out this entity if clinical suspicion is high.

Pancreatitis

CT depicts fat-stranding (arrowheads) surrounding the primary focus of the inflammation: the pancreas.

Conclusion

In patients with an acute abdomen 'the stakes are high'.

A misdiagnosis may have serious consequences. We advocate a systematic approach:

1. First focus on the most common diseases and make a firm diagnosis or exclude them.

2. Always screen the whole abdomen for general signs of pathology.