Shoulder Anatomy and Variants on MRI

Robin Smithuis and Henk Jan van der Woude

Radiology department of the Alrijne hospital, Leiderdorp and the Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

The glenohumeral joint has a greater range of motion than any other joint in the body.

The small size of the glenoid fossa and the relative laxity of the joint capsule renders the joint relatively unstable and prone to subluxation and dislocation.

MR is the best imaging modality to examen patients with shoulder pain and instability.

In Shoulder MR-Part I we will focus on the normal anatomy and the many anatomical variants that may simulate pathology.

In part II we will discuss shoulder instability.

In part III we will focus on impingement and rotator cuff tears.

Introduction

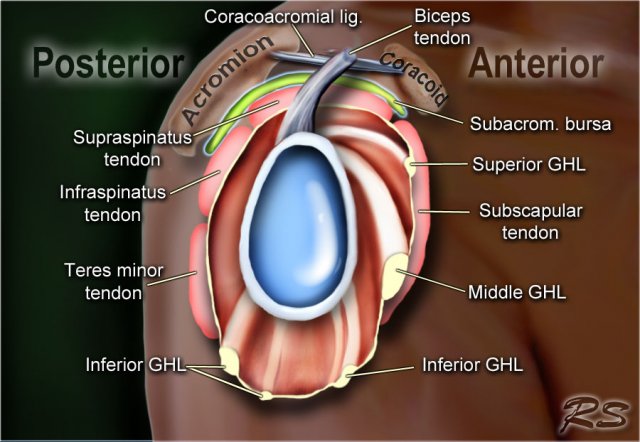

The glenohumeral joint has the following supporting structures:

-

Superiorly

- coracoacromial arch and coracoacromial ligament

- long head of the biceps tendon

- tendon of the supraspinatus muscle

-

Anteriorly

- anterior labrum

- glenohumeral ligaments - SGHL, MGHL, IGHL (anterior band)

- subscapularis tendon

-

Posteriorly

- posterior labrum

- posterior band of the IGHL

- infraspinatus and teres minor tendon

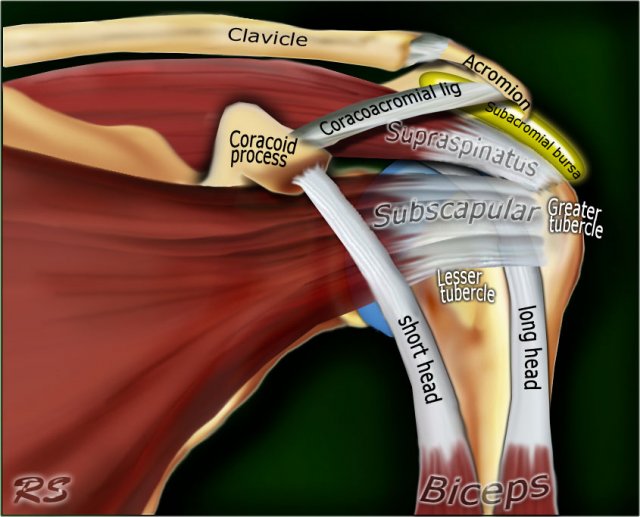

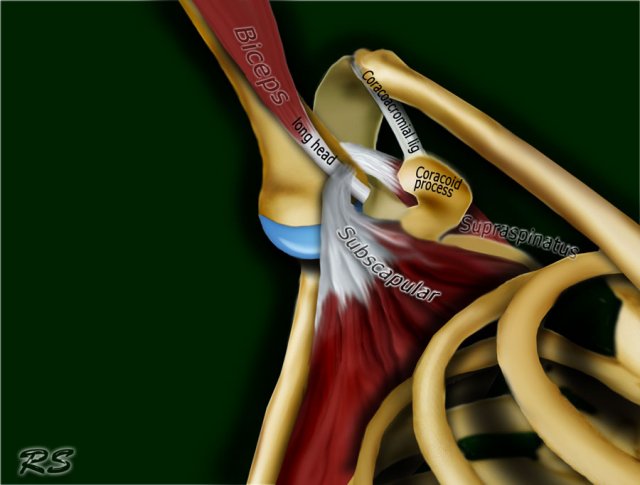

Anterior view

The tendon of the subscapularis muscle attaches both to the lesser tuberosity aswell as to the greater tuberosity giving support to the long head of the biceps in the bicipital groove.

Dislocation of the long head of the biceps will inevitably result in rupture of part of the subscapularis tendon.

The rotator cuff is made of the tendons of subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor muscle.

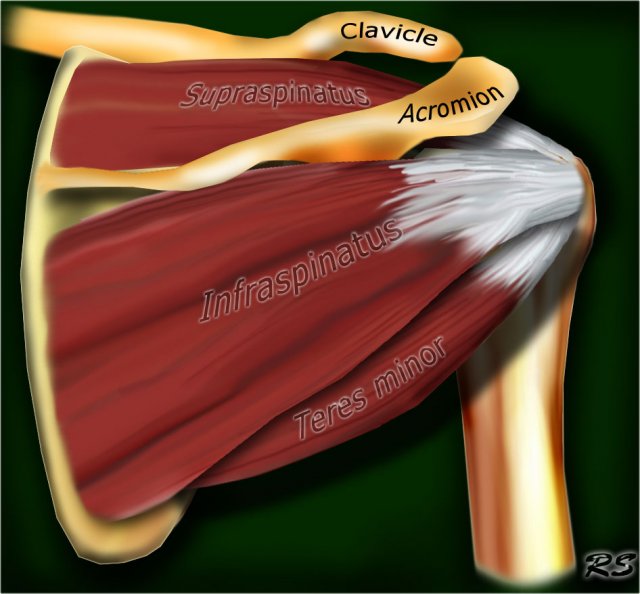

Posterior view

The supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor muscles and tendons are shown. They all attach to the greater tuberosity.

The rotator cuff muscles and tendons act to stabilize the shoulderjoint during movements.

Without the rotator cuff, the humeral head would ride up partially out of the glenoid fossa, lessening the efficiency of the deltoid muscle.

Large tears of the rotator cuff may allow the humeral head to migrate upwards resulting in a high riding humeral head.

Normal anatomy

Axial anatomy and checklist

- Look for an os acromiale.

- Notice that the supraspinatus tendon is parallel to the axis of the muscle. This is not always the case.

- Notice that the biceps tendon is attached at the 12 o'clock position. The insertion has a variable range.

- Notice superior labrum and attachment of the superior glenohumeral ligament.

At this level look for SLAP-lesions and variants like sublabral foramen.

At this level also look for Hill-Sachs lesion on the posterolateral margin of the humeral head. - The fibers of the subscapularis tendon hold the biceps tendon within its groove. Study the cartilage.

- At this level study the middle GHL and the anterior labrum. Look for variants like the Buford complex. Study the cartiage.

- The concavity at the posterolateral margin of the humeral head should not be mistaken for a Hill Sachs, because this is the normal contour at this level.

Hill Sachs lesions are only seen at the level of the coracoid.

Anteriorly we are now at the 3-6 o'clock position. This is where the Bankart lesion and variants are seen. - Notice the fibers of the inferior GHL. At this level also look for Bankart lesions.

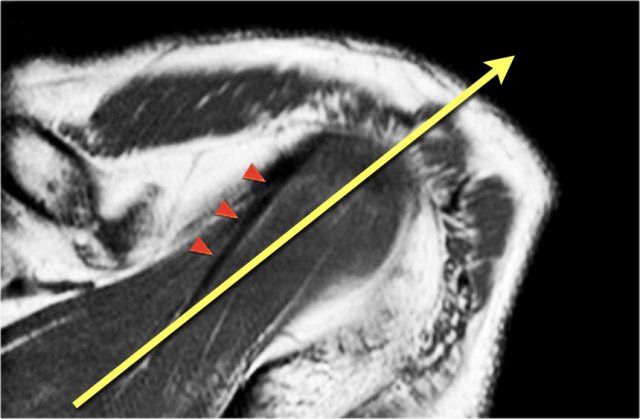

Axis of supraspinous tendon

The supraspinatus tendon is the most important structure of the rotator cuff and subject to tendinopathy and tears.

Tears of the supraspinatus tendon are best seen on coronal oblique and ABER-series.

In many cases the axis of the supraspinatus tendon (arrowheads) is rotated more anteriorly compared to the axis of the muscle (yellow arrow).

When you plan the coronal oblique series, it is best to focus on the axis of the supraspinatus tendon.

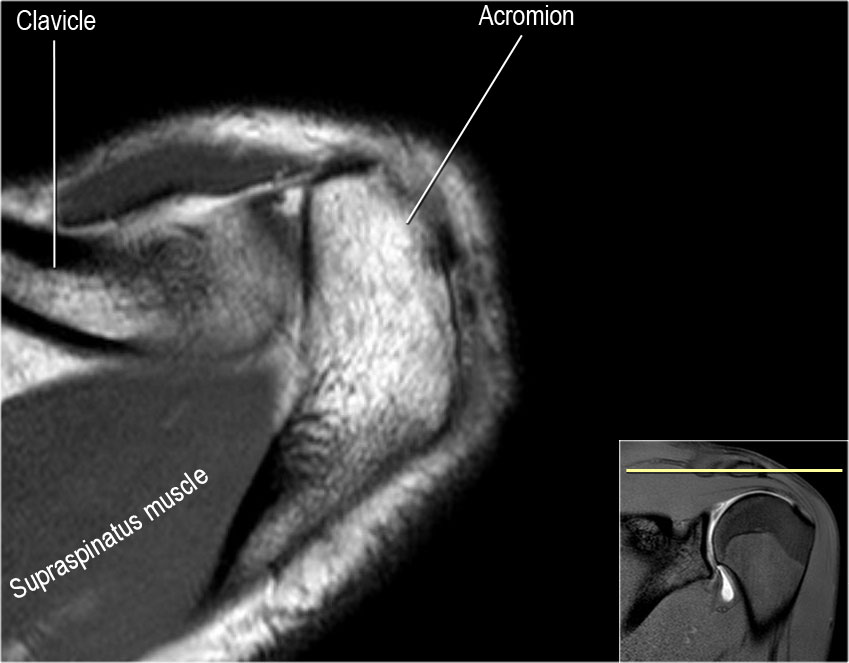

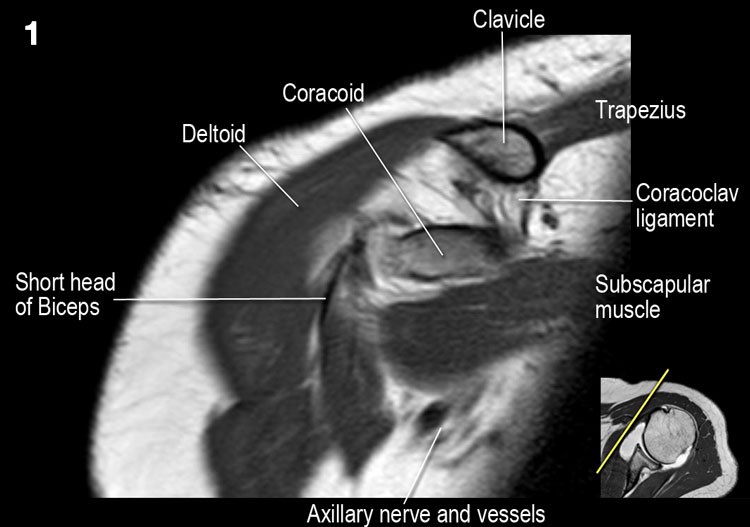

Coronal anatomy and checklist

- Notice coracoclavicular ligament and short head of the biceps.

- Notice coracoacromial ligament.

- Notice suprascapular nerve and vessels.

- Look for supraspinatus-impingement by AC-joint spurs or a thickened coracoacromial ligament

- Study the superior biceps-labrum complex and look for sublabral recess or SLAP-tear.

- Look for excessive fluid in the subacromial bursa and for tears of the supraspinatus tendon.

- Look for rim-rent tears of the supraspinatus tendon at the insertion of the anterior fibers.

- Study the attachment of the IGHL at the humerus. Study the inferior labral-ligamentary complex. Look for HAGL-lesion (humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament).

- Look for tears of the infraspinatus tendon.

- Notice small Hill-Sachs lesion.

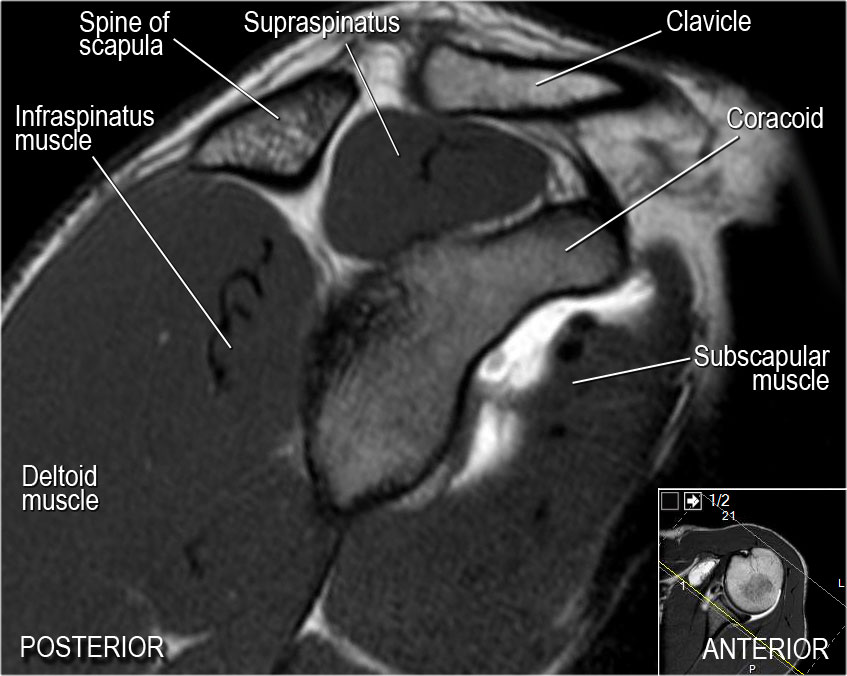

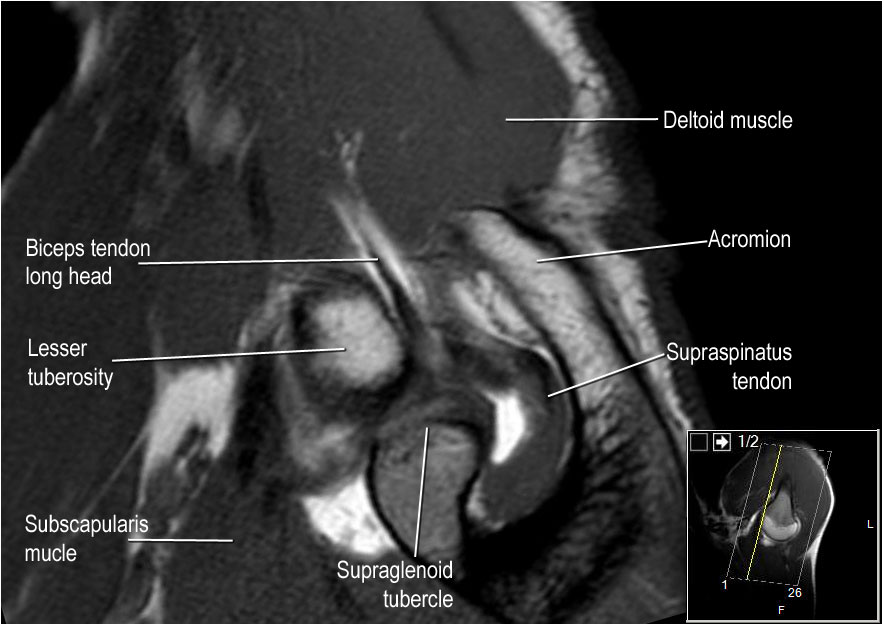

Sagittal anatomy and checklist

- Notice rotator cuff muscles and look for atrophy

- Notice MGHL, which has an oblique course through the joint and study the relation to the subscapularis tendon.

- Sometimes at this level labral tears at the 3-6 o'clock position can be visualized.

- Study the biceps anchor.

- Notice shape of the acromion

- Look for impingement by the AC-joint. Notice the rotator cuff interval with coracohumeral ligament.

- Look for supraspinatus tears.

ABER view

Labral tears

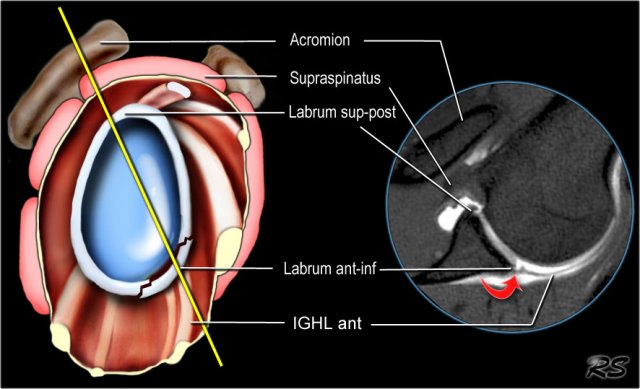

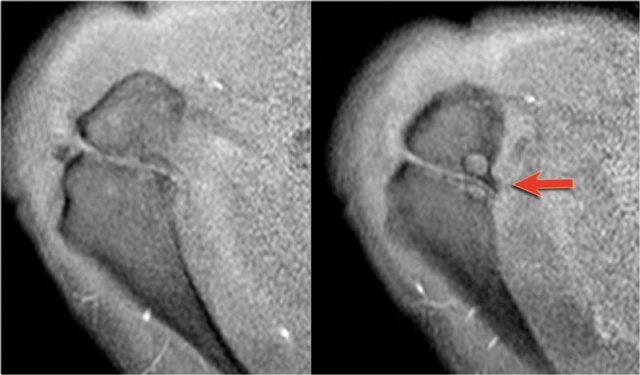

The abduction external rotation (ABER) view is excellent for assessing the anteroinferior labrum at the 3-6 o'clock position,

where most labral tears are located.

In the ABER position the inferior glenohumeral ligament is stretched resulting in tension on the anteroinferior labrum, allowing intra-articular contrast to get between the labral tear and the glenoid.

Rotator cuff tears

The ABER view is also very useful for both partial- and full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff.

The abduction and external rotation of the arm releases tension on the cuff relative to the normal coronal view obtained with the arm in adduction.

As a result, subtle articular-sided partial thickness tears will not lie apposed to the adjacent intact fibers of the remaining rotator cuff

nor be effaced against the humeral head, and intra-articular contrast can enhance visualization of the tear (3).

Images in the ABER position are obtained in an axial way 45 degrees off the coronal plane (figure).

In that position the 3-6 o'clock region is imaged perpendicular.

Notice red arrow indicating a small Perthes-lesion, which was not seen on the standard axial views.

ABER - anatomy

- Notice the biceps anchor. The undersurface of the supraspinatus tendon should be smooth.

- Look for supraspinatus irregularities.

- Study the labrum in the 3-6 o'clock position. Due to the tension by the anterior band of the inferior GHL labral teras will be easier to detect.

- Notice smooth undersurface of infraspinatus tendon and normal anterior labrum.

- Notice smooth undersurface of infraspinatus tendon and normal anterior labrum.

Labral variants

There are many labral variants.

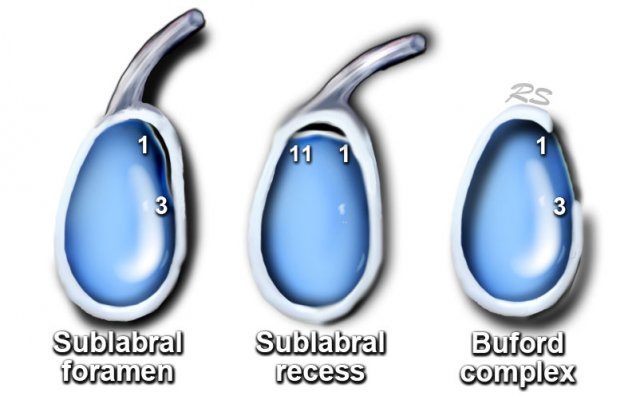

These normal variants are all located in the 11-3 o'clock position.

It is important to recognise these variants, because they can mimick a SLAP tear.

These normal variants will usually not mimick a Bankart-lesion, since it is located at the 3-6 o'clock position, where these normal variants do not occur. However labral tears may originate at the 3-6 o'clock position and subsequently extend superiorly.

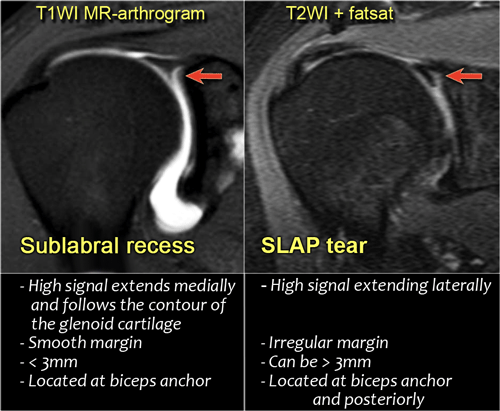

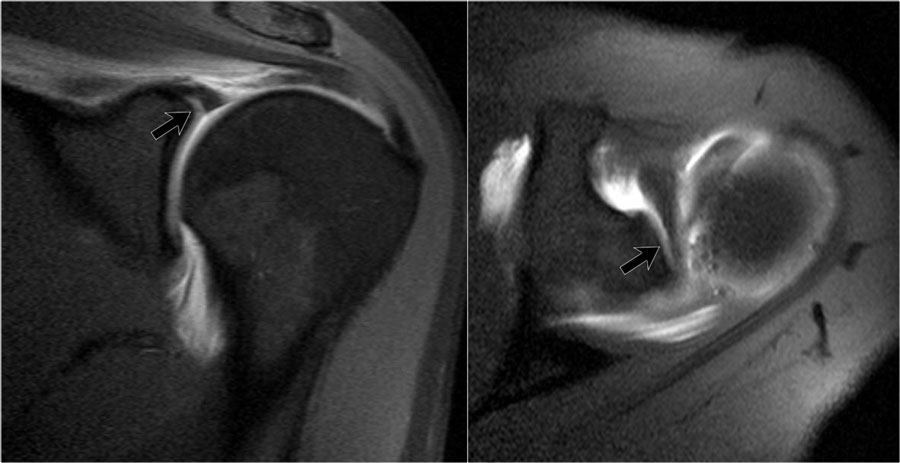

Sublabral recess

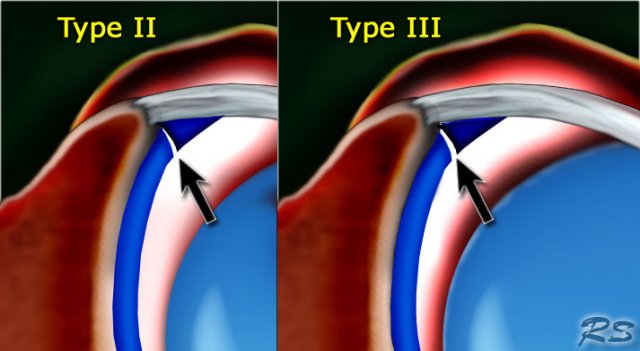

There are 3 types of attachment of the superior labrum at the 12 o'clock position where the biceps tendon inserts.

In type I there is no recess between the glenoid cartilage and the labrum.

In type II there is a small recess.

In type III there is a large sublabral recess.

This sublabral recess can be difficult to distinguish from a SLAP-tear or a sublabral foramen.

These images illustrate the differences between an sublabral recess and a SLAP-tear.

A recess more than 3-5 mm is always abnormal and should be regarded as a SLAP-tear.

The image shows the typical findings of a sublabral recess.

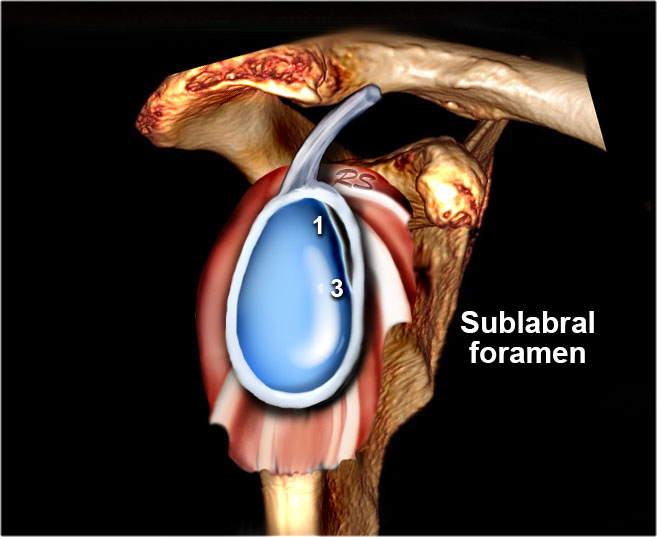

Sublabral Foramen

A sublabral foramen or sublabral hole is an unattached anterosuperior labrum at the 1-3 o'clock position.

It is seen in 11% of individuals.

On a MR-arthtrogram a sublabral foramen should not be confused with a sublabral recess or SLAP-tear, which are also located in this region.

A sublabral recess however is located at the site of the attachment of the biceps tendon at 12 o'clock and does not extend to the 1-3 o'clock position.

A SLAP tear may extend to the 1-3 o'clock position, but the attachment of the biceps tendon to the superior labrum should always be involved.

Scroll through the images and notice the unattached labrum at the 12-3 o'clock position at the site of the sublabral foramen.

Notice the smooth borders unlike the margins of a SLAP-tear.

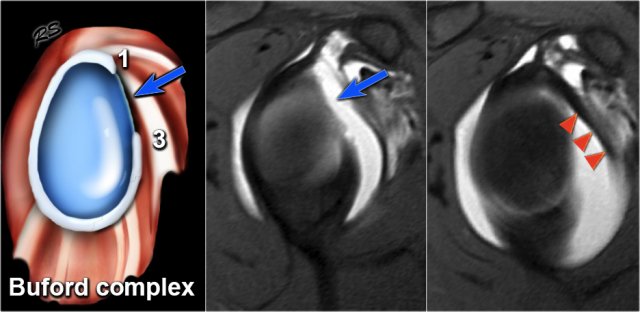

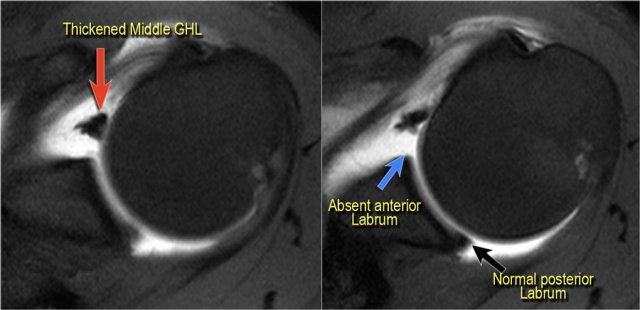

Buford complex

A Buford complex is a congenital labral variant.

The anterosuperior labrum is absent in the 1-3 o'clock position and the middle glenohumeral ligament is usually thickened.

It is present in approximately 1.5% of individuals.

On these axial images a Buford complex can be identified.

The anterior labrum is absent in the 1-3 o'clock position and there is a thickened middle GHL.

The thickened middle GHL should not be confused with a displaced labrum.

It should always be possible to trace the middle GHL upwards to the glenoid rim and downwards to the humerus.

Video of Buford complex

Os Acromiale

Failure of one of the acromial ossification centers to fuse will result in an os acromiale.

It is present in 5% of the population.

Usually it is an incidental finding and regarded as a normal variant.

The os acromiale may cause impingement because if it is unstable, it may be pulled inferiorly during abduction by the deltoid, which attaches here.

On MR an os acromiale is best seen on the superior axial images.

An os acromiale must be mentioned in the report, because in patients who are considered for subacromial decompression,

the removal of the acromion distal to the synchondrosis may further destabilize the synchondrosis and allow for

even greater mobility of the os acromiale after surgery and worsening of the impingement (4).

The axial MR-images show an os acromiale with degenerative changes, i.e. subchondral cysts and osteophytes (arrow).