Swallowing disorders update

Robin Smithuis

Radiology department of the Alrijne Hospital in Leiderdorp, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

Swallowing is a complex movement.

It requires the coordination of nerves and muscles in the buccolabial area, the tongue, the palate, the pharynx, the larynx and finally the esophagus.

Radiographic studies of patients with swallowing disorders can help to analyse the problem.

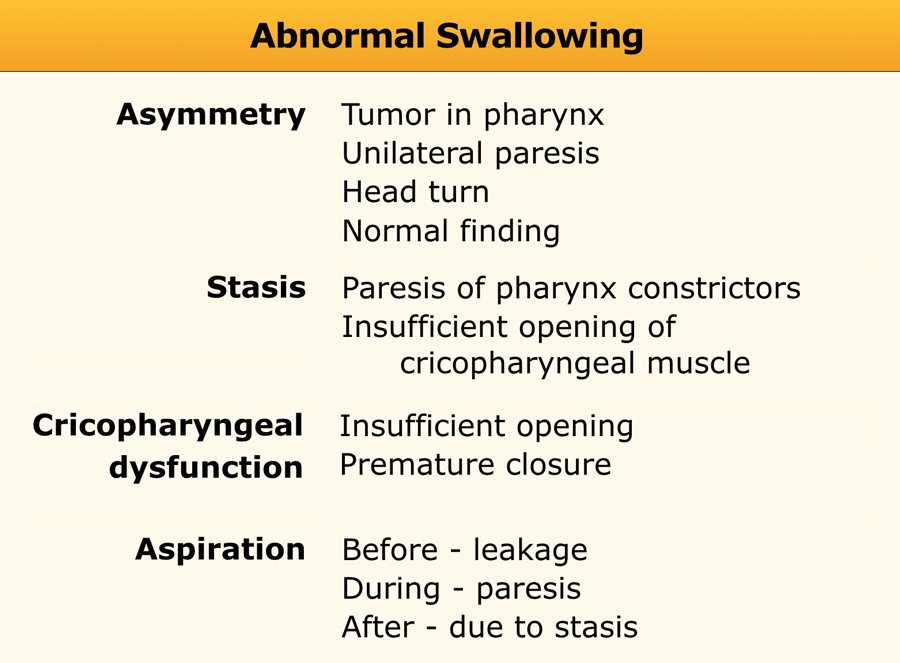

In this article a systematic approach on how to analyse these videos is presented by focussing on four basic findings:

- Asymmetric swallowing

- Stasis of contrast

- Cricopharyngeal dysfunction

- Aspiration

Normal Swallowing

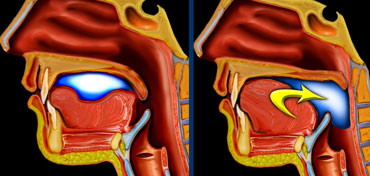

LEFT: Oral or preparatory phase. RIGHT: Transport to pharynx and subsequent triggering of the actual swallowing reflex.

LEFT: Oral or preparatory phase. RIGHT: Transport to pharynx and subsequent triggering of the actual swallowing reflex.

Oral phase

In the oral phase food is prepared for swallowing and then transported to the pharynx.

This is a preparatory phase in which the food is held within the mouth while the base of the tongue and the soft palate close the oral cavity posteriorly to prevent food spilling into the open larynx and trachea.

A bolus is formed in the central portion of the tongue and then pushed posteriorly toward the pharynx with an anterior-to-posterior tongue elevation.

As the bolus enters the pharynx the actual swallow or pharyngeal reflex is triggered.

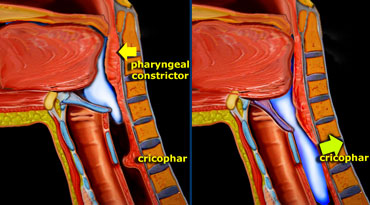

LEFT: Pharyngeal constrictors push the bolus down. RIGHT: Together with the contraction of the inferior constrictor, the cricopharyngeus relaxes.

LEFT: Pharyngeal constrictors push the bolus down. RIGHT: Together with the contraction of the inferior constrictor, the cricopharyngeus relaxes.

Pharyngeal phase

This phase is a reflex action.

The bolus passes through the pharynx quickly and then enters the esophagus.

This takes place in less than a second.

The initiation of this process starts when the bolus passes the anterior faucial arch and reaches the posterior pharyngeal wall.

Elevation of the soft palate prevents material from entering the nasal cavity.

This stage is followed by the pharyngeal constrictor muscles pushing the bolus further into the pharynx, toward the cricopharyngeal sphincter.

The larynx prevents material from entering the trachea by respectively closing the true vocal cords, false vocal folds, and aryepiglottic folds.

Contraction of the lower pharyngeal constrictor is followed by relaxation of the cricopharyngeal muscle, allowing the bolus to pass into the esophagus.

Fluoroscopic imaging

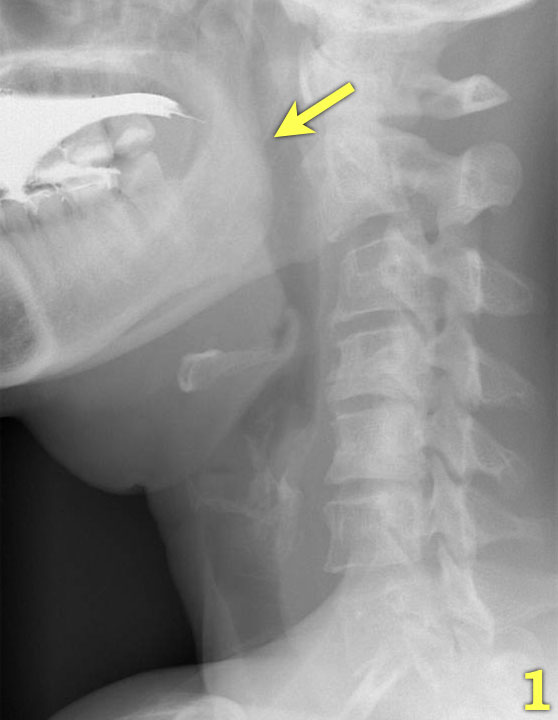

The most important images of the swallowing study are those taken of the lateral view.

Click through the images 1-7 on the left.

- The base of the tongue and the soft palate close the oral cavity posteriorly (arrow) to prevent spill of food into the pharynx and open larynx.

- The tongue start to transport the food towards the pharynx (yellow arrow).

The larynx is still open and in its normal position (green arrow). - the soft palate elevates to prevent spill into the nasopharynx (green arrow) and the tongue pushes the food further backwards (yellow arrow)

- The hyoid bone elevates and the larynx closes (green arrow). The tongue pushes the food downwards, while the upper esophageal constrictor contracts.

- Contraction of the middle pharyngeal constrictor (yellow arrow), while the cricopharyngeus is already fully relaxed (green arrow).

- Contraction of the lower pharyngeal constrictor emptying the pharynx.

- Epiglottis elevates to regain its resting position and the larynx opens (arrow).

Video of lateral view

Watch in HD.

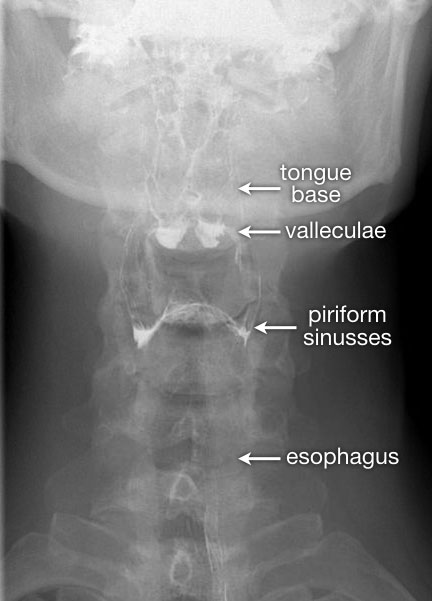

The AP-view is important to look for asymmetry.

Once the series of the pharyngeal phase has been acquired, follow the contrast bolus all the way down to the gastroesophageal junction.

Indications for a study

Indications for a swallowing study are dysphagia, globus sensation and aspiration.

Dysphagia is a general term used to describe the inability to transport the food properly from the mouth to the stomach.

Globus sensation is a term to describe the feeling, that there is something in the throat, that is in the way or needs to be swallowed.

Aspiration is the most severe form of swallowing disorders and can result in aspiration pneumonia, chronic lung disease or choking.

In some patients with chronic lung disease a swallowing study can be performed to look for 'silent aspiration'.

Study of Swallowing

First try to find out exactly what the patients problem is, so you can customize the series.

Is there a risk of aspiration, i.e. wet voice, recurrent pneumonia or aspiration?

If so, do not start the examination with barium contrast, but instead use non-ionic water-soluble contrast.

If during the first few swallows there is no aspiration, you can switch to barium, as this gives better quality images.

Before we start the examination, the procedure is explained to the patient and we practise certain manoeuvres like the modified Valsalva (figure).

When solid food is the problem, you may want to add a solid substance to the barium - for instance biscuits or bread with bariumpaste.

The patient in the video only has problems with solid food.

The examination of patients with a possible swallowing disorder consists of:

- Fluorographic study of the actual swallowing.

- Double-contrast images of the pharynx.

- Examination of the esophagus.

Start with one or two lateral swallows followed by a lateral double-contrast view of the pharynx (see later).

Then an AP-swallow is recorded followed by an AP double-contrast view of the pharynx.

Next the passage through the esophagus is recorded, sometimes followed by double-contrast views of the gastroesophageal junction.

Fluorographic study of the actual swallowing

The act of swallowing is recorded on video or some sort of digital recording.

We use grabs from the fluographic images and store them into the PACS-system, where we can play the images back and forth in slow motion.

It is very important to always start with the lateral view first, because if the patient aspirates, the lateral view will tell you how and why it happened.

If you have to stop the examination, the most important images will already have been recorded.

If you start with an AP-view and the patient aspirates, you may have to stop the examination and you will never know why aspiration occurred and what the problem is.

If a patient is unable to stand or sit, you can still do a lateral view.

Use only a small amount of barium for the first swallow and if the patient is doing fine, coninue with larger portions.

Aspiration of a small amount of barium is usually not a big problem, but you don't want a lot of barium filling the bronchi.

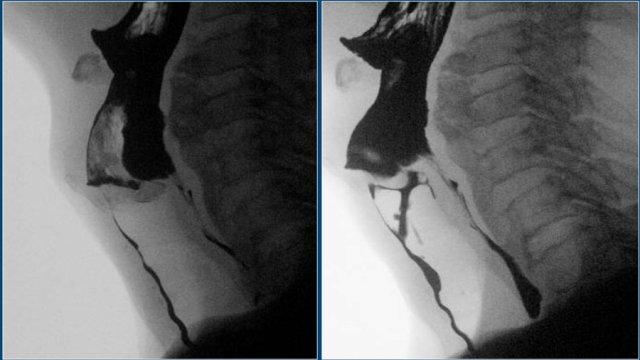

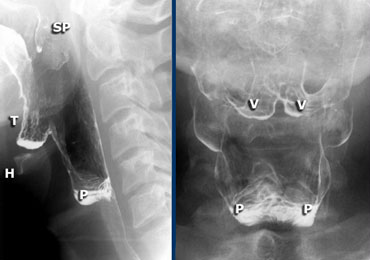

LEFT: Lateral view during singing aaa. Hyoid (H) and tongue base (T) move anteriorly. Left and right pyriform sinuses are projected on top of each other. Tip of soft palate (SP) is seen. RIGHT: Valleculae (V) and pyriform sinuses (P).

LEFT: Lateral view during singing aaa. Hyoid (H) and tongue base (T) move anteriorly. Left and right pyriform sinuses are projected on top of each other. Tip of soft palate (SP) is seen. RIGHT: Valleculae (V) and pyriform sinuses (P).

Double contrast images of the pharynx

For the lateral view, ask the patient to sing an aaa, as this will move the tongue in an anterior position and give a better view on the oro- and hypopharynx.

In Dutch this will be the letter eee, as it is pronounced the same as the english aaa.

For the AP-view the modified Valsalva manoeuvre is performed.

The patients has to blow air through the tightened lips as in trumpet-playing, while relaxing the neck region.

Always practise this manoeuvre prior to the examination, so the patient knows what to do.

On the left DC views of the pharynx.

Outpounching of the lateral wall of the pharynx is normal and can be quite severe (Dizzy Gillespie).

These are called 'lateral pharyngeal ears'.

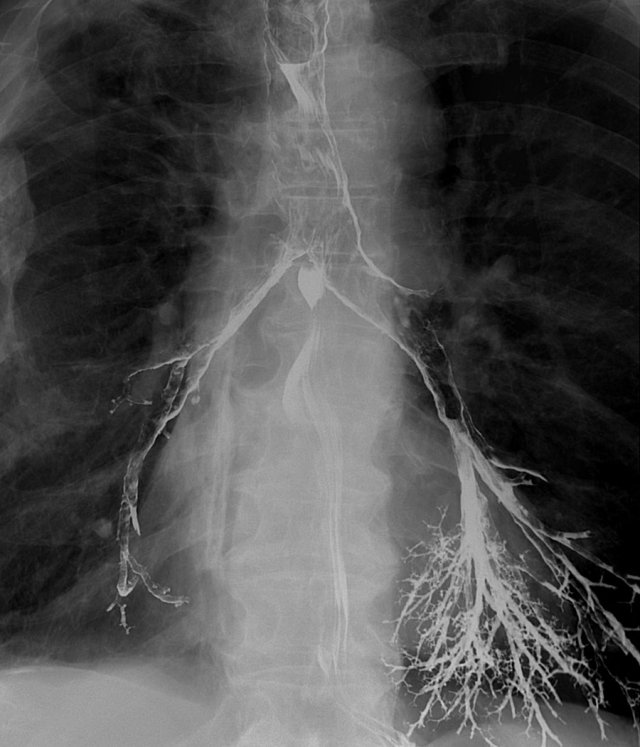

Examination of the esophagus

Always follow the passage of barium through the esophagus until it enters the stomach.

Disorders of the gastroesophageal junction are often experienced as a problem within the throat.

The rationale for this is that in patients with a distal obstruction, gastroesophageal reflux or a motility disorder, the cricopharyngeal muscle has to work very hard to prevent foodspillage back into the pharynx - along with the risk of aspiration.

This increased muscle tone gives the patient the sensation that there is something in the throat.

The images are of a patient with globus sensation.

This was due to severe reflux and subsequent increased tone of the cricopharyngeal muscle.

A large paraesophageal hernia with reflux is the cause of the complaints.

Optimal views of gastro-esophageal junction when air regurgitates from the stomach into the coated esophagus in a patient with a sliding hiatus hernia.

Optimal views of gastro-esophageal junction when air regurgitates from the stomach into the coated esophagus in a patient with a sliding hiatus hernia.

Excellent views of the gastroesophageal junction can be achieved by doing the following:

- Ask the patient to swallow zoru-granules (or coca cola) for optimal gas filling of the stomach.

- Tell the patient not to belch, but to keep the air in the stomach until the moment of swallowing.

- Place the patient in the left anterior oblique position.

- Lift the table top 45 degrees.

- Swallow high density barium for optimal esophageal coating.

- Images are taken when air regurgitates from the stomach into the barium-coated esophagus.

You get the best lighting, when the anterior part of the cervical spine is in the middle of the image.

Do not put the contrast bolus in the center of the image, because on the video you'll get a constant shift of images that are too dark to images that are too bright.

Analyzing swallowing studies

A simple way to analyse a swallowing study is to concentrate on four easily detectable findings:

- Asymmetry

- Stasis

- Cricopharyngeal dysfunction

- Aspiration

These findings are mostly already apparent during the examination, but analysis of all the images will clarify the mechanism that causes these abnormal findings.

These imaging findings may be isolated findings or may be related to each other.

For instance, premature closure of the cricopharyngeal muscle may lead to stasis of contrast in the pharynx, which may result in aspiration as the larynx opens at the end of swallowing.

Asymmetric swallowing due to head turn. The head is turned to the left and contrast is only seen in the right food channel.

Asymmetric swallowing due to head turn. The head is turned to the left and contrast is only seen in the right food channel.

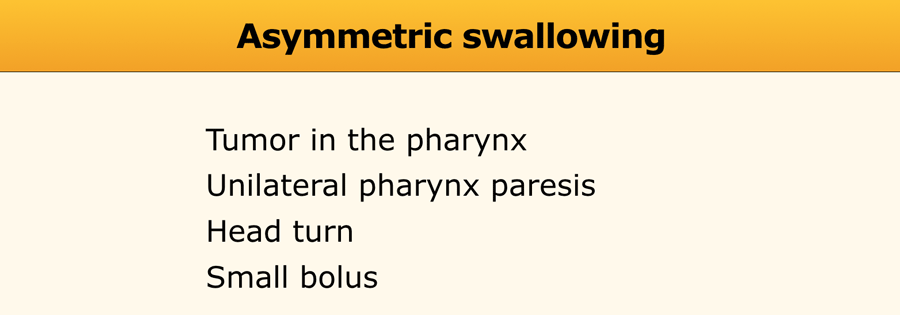

Asymmetry

Asymmetric swallowing on an AP-view is usually the result of an asymmetric tilting of the epiglottis.

Sometimes it is caused by rotation of the head, but in many cases no real explanation is found.

Even when the head is not rotated, the epiglottis can tilt asymmetrically when it hits the posterior pharyngeal wall.

This is more likely to occur when only a small bolus is given, as the pharynx will not fully distend.

A larger bolus will result in a symmetric swallow.

In the case on the left rotation of the head closes the side to which the head is turned (Figure).

If a patient has a unilateral pharyngeal paresis, turning of the head towards the affected side will help the patient in preventing aspiration.

By turning the head towards the affected side, this side will be closed preventing stasis on this side and possible secondary aspiration.

However before you decide that it is a normal finding you have to exclude a pharyngeal tumour or unilateral paresis.

The double-contrast views can be helpful in these cases.

In unilateral paresis the paralysed side will protrude during the modified Valsalva.

When a tumour is present in the pharynx, it is usually visible on the DC views.

Sometimes endoscopy is necessary to solve the problem of an asymmetric swallow.

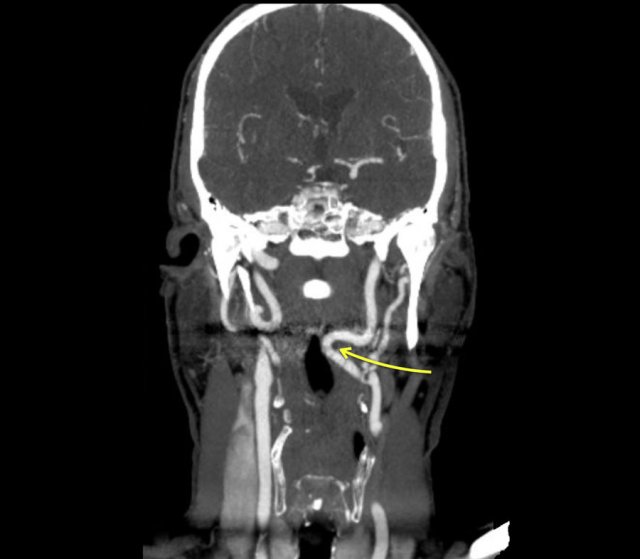

Asymmetry (2)

The case on the left is an odd case, but it nicely demonstrates the difficulty that sometimes exists in determining the cause of asymmetry.

On the far left asymmetry is seen on the fluorographic study (green arrow).

It looks as if there is something in the right pyriform sinus.

On the double contrast view on the right the pyriform sinus is normal (green arrow), but at the level of the vallecula on the right a lobulated proces is seen (yellow arrow).

At a higher level a smooth indentation of the oropharynx is seen (blue arrow).

The lobulated tumor at the level of the valleculae proved to be remnants of the lingual tonsil, which is a common finding and sometimes difficult to differentiate from cancer of the tongue base.

Continue with the CT of this patient.

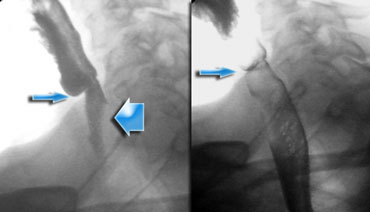

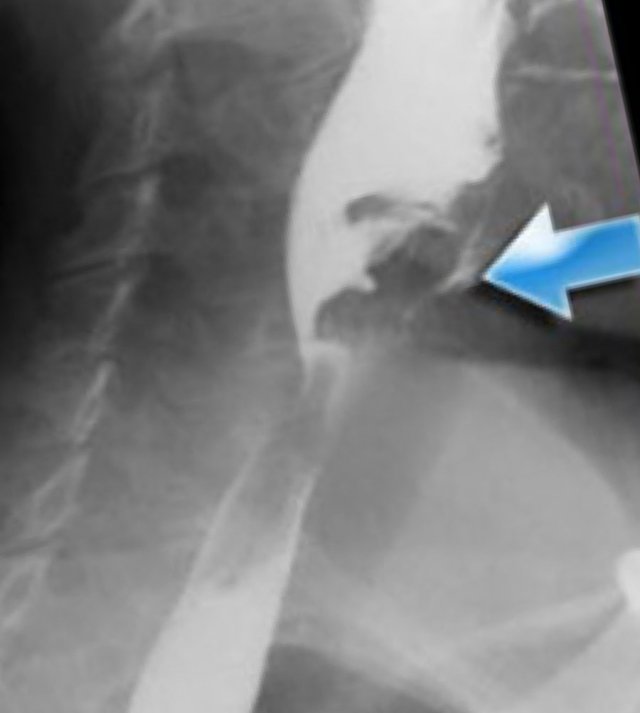

Impression of the oropharynx by an elongated internal carotid artery (blue arrow.). Compare to the position of the carotid artery on the left

Impression of the oropharynx by an elongated internal carotid artery (blue arrow.). Compare to the position of the carotid artery on the left

The CT image shows that the smooth indentation of the oropharynx on the right was caused by an elongated internal carotid artery.

So indeed this is an uncommon case in which on the fluorographic study a tumor was suspected in the pyriform sinus.

Finally a proces was found within the oropharynx and a proces compressing the wall from outside at a higher level.

Due to these processes there was an asymmetric passage of contrast in the hypopharynx simulating a proces in the pyriform sinus.

Here another patient with an elongated internal carotid artery.

This patient had swallowing problems and at inspection a pulsating structure was seen in the oropharynx.

This is not un uncommon finding.

So before you perform a biopsy in this area make sure that you are not dealing with the carotid artery.

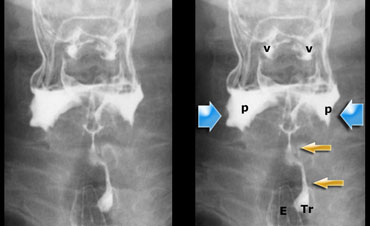

Stasis of contrast at the level of the pyriform sinuses (blue arrows) with subsequent aspiration (yellow arrows)

Stasis of contrast at the level of the pyriform sinuses (blue arrows) with subsequent aspiration (yellow arrows)

Stasis

Stasis is the result of insufficient cleansing of the pharynx, either due to an obstruction- i.e. dysfunction of the cricopharyngeus or tumor or due to insufficient contraction of the pharyngeal constrictors.

Insufficient contraction is the result of pharyngeal paresis resulting from a neuromuscular disorder.

Excessive movements of the tongue base and larynx are sometimes seen on lateral fluorographic studies to compensate for the loss of function of the pharyngeal constrictors.

When the patient resumes breathing, aspiration can occur (Figure).

Stasis (2)

Here a set of images demonstrating a patient with a paresis of the pharynxconstrictors.

This is usually associated with insufficient relaxation of the cricopharyngeal muscle.

In this example we can see how the patient tries to compensate for the loss of pharyngeal constriction by excessive movement of the tongue and the head.

This patient is in extreme stress, because he knows that when he starts breathing and the throat is not empty, he will aspirate.

- 1-3. No contraction of the posterior wall of the pharynx is seen. Cricopharyngeus does not open properly.

- 4-7. Contrast enters the larynx, but does not enter the trachea.

- 8-10. Excessive movements of the head in order to squeeze the bolus into the esophagus.

In some of these cases cricopharyngeotomy is the only solution to facilitate the passage of food to the esophagus.

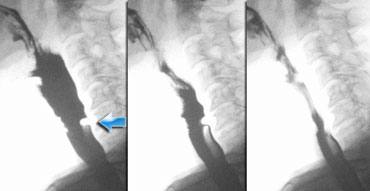

Cricopharyngeal Dysfunction

Insufficient opening and premature closure are the most common problems of the cricopharyngeal muscle.

Normally you should not see an impression of the cricopharyngeus during passage of the bolus, but a small non-obstructive indentation is sometimes seen and is not clinically significant (Figure).

It can however sometimes explain the symptoms of the patient.

It is assumed that the passage of food irritates the mucosa that covers the cricopharyngeal muscle resulting in a globus sensation.

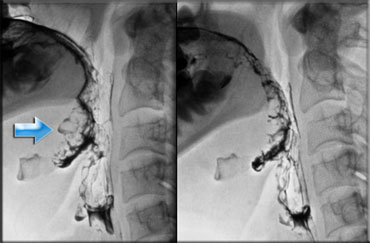

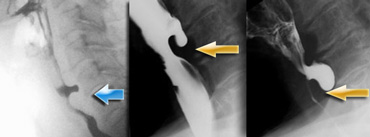

LEFT: small pouch. MIDDLE and RIGHT: true Zenker's diverticulum due to premature closure of the cricopharyngeus (yellow arrow)

LEFT: small pouch. MIDDLE and RIGHT: true Zenker's diverticulum due to premature closure of the cricopharyngeus (yellow arrow)

Zenker's diverticulum

A Zenker's diverticulum is always the result of cricopharyngeal dysfunction.

Premature closure of the cricopharyngeus results in an increased pressure in the hypopharynx, just above the cricopharyngeus, as the pressurewave of the pharyngeal constrictors pushes the bolus downwards.

This increased pressure can result in an outpouching at a weak spot in the posterior pharyngeal wall (Killian's dehiscence).

First this will result in a small pouch, that in time can increase and form a true Zenker's diverticulum (Figure).

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction (3)

On the left a patient who complained of globus sensation in the throat and difficulty of swallowing with regurgitation of undigested food.

The digital recordings nicely demonstrate the filling of a large Zenker's diverticle.

The contraction of the lower pharyngeal constrictors is indicated by the blue arrow.

The contraction of the lower pharyngeal muscle against the closed cricopharyngeal muscle causes the posterior outpouching, just above the contracted cricopharyngeal muscle (yellow arrow).

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction (4)

Here a video of a patient with a Zenker diverticulum.

Notice that on the AP-view the patient keeps on swallowing because of the globus sensation.

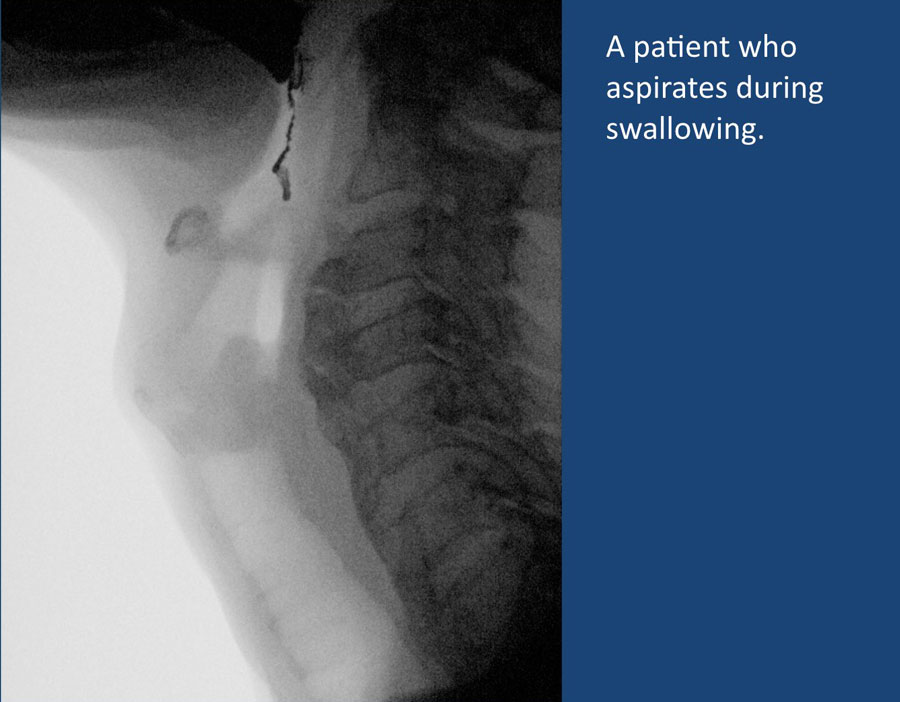

Aspiration

There are three instances when aspiration can occur: before, during or after the actual swallow.

- Aspiration before swallowing is either the result of insufficient closure of the oral cavity during the preparatory phase or inability to start the swallow reflex when contrast enters the pharynx.

- Aspiration during swallowing is due to insufficient closure of the larynx.

- Aspiration after swallowing is the result of stasis of contrast in the pharynx - when the larynx opens the contrast leaks into the trachea.

Aspiration before swallowing

When tongue or soft palate are unable to prevent spillage of food into the pharynx, aspiration may occur since the larynx is still open.

Weakness of these muscles in the mouth and the throat is due to paralysis or myopathy.

- Notice that contrast enters the pharynx, but does not trigger a swallowing reflex.

- No swallowing reflex

- Contrast reaches the hypopharynx, but still no swallowing reflex.

- Contrast enters the larynx, which is still open and not yet elevated

- At this moment the swallowing reflex starts and the larynx elevates

- Contrast is transported to the esophagus and the larynx closes, but there is already contrast in the trachea.

- Proper relaxation of the cricopharyngeus and finally there is good closure of the larynx.

- Notice that there is no stasis at the end of the swallow .

We have to assume that a failure of the sensory nerves in the pharynx is the problem.

Notice also that there is no coughing reflex.

This patient probably has silent aspiration.

Aspiration during swallowing

This is due to an insufficient closure of the larynx when it should be closed.

Closure of the larynx is a result of anterosuperior lifting of the larynx which allows the true cords, false cords and finally, the aryepiglottic folds to contract, followed by a backwards folding of the epiglottis over the closed larynx.

The aryepiglottic folds are the main gatekeepers, while the epiglottis plays only a minor role in preventing aspiration.

Both failure of these intrinsic muscles of the larynx as well as failure of the extrinsic muscles (i.e. muscles that lift the larynx) may lead to aspiration during swallowing.

Weakness of the extrinsic muscles is seen after radiotherapy, in neurologic disorders and in recurrens nerve paralysis (i.e. neuromuscular dysfunction).

Notice that this patient has diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) with syndesmofytes at many levels on the anterior side of the cervical spine.

However they are not the cause of the swallowing disorder.

Aspiration during swallowing (2)

On the left a digital recording of a patient who complained of a sore throat and a wet voice.

Notice that when the contrast enters the throat, the swallowing reflex is not triggered immediately.

This allows for barium contrast to enter the larynx, where it sits on the vocals cords.

Once the swallowing reflex is initiated, the larynx closes properly, but contrast is already in.

Notice also that while the contrast enters the larynx, it does not initiate a cough reflex.

Althoug the digital recording perfectly explains the complaints of the patient, it is difficult to say what causes this problem.

Usually when there is aspiration during swallowing, the problem is at the level of the larynx.

Mostly it is the larynx that is unable to close either due to weakness of the intrinsic laryngeal muscles or weakness of the extrinsic muscles that lift the larynx and allow it to contract (for instance after neck radiation or surgery).

In this case the problem is probably at the level of the sensory nerves in the pharynx, who are not triggered properly.

You could also argue, that this maybe is aspiration before swallowing, because it happens before the actual swallowing reflex.

Maybe a more forcefull push of the bolus posteriorly from the mouth into the oropharynx could help in triggering these nerves instead of allowing the bolus to slide over the back of the tongue.

Aspiration after swallowing

This is the most common cause of aspiration.

It is the result of stasis of contrast in the pharynx due to insufficient contraction of the pharyngeal constrictors or insufficient opening of the cricopharyngeal muscle or an obstructing web or tumor.

When the larynx opens the contrast may leak into the trachea.

The patient in the video aspirates due to stasis in the hypopharynx.

In this video there is massive aspiration due to stasis as a result of insufficient contraction of the pharyngeal constrictors and insufficient opening of the cricopharyngeal muscle.

Web

Webs are mucosa folds which are usually located anteriorly in the hypopharynx or upper esophagus.

Liquids usually pass well, but in many cases a 'jet' is seen.

The passage of solid food may produce irritation or damage to the mucosa, resulting in a globus feeling.

They are best diagnosed on the lateral projection of the barium swallow.

Here another example of a web.

Webs are frequently overlooked at esophagoscopy unless special attention is given to this area.

During esophagoscopy they may rupture, but in many cases recurrence is seen.

Pharyngeal ears

Outpounching of the lateral wall of the pharynx are called 'lateral pharyngeal ears'.

Sometimes patients complain of globus sensation or that small food particles or pills get stuck in their throat, but usually it is an incidental finding.

They can be quite prominent as in Dizzy Gillespie the famous trumpet player.

Two cases of pharyngeal ears.

Osteofytes

Although osteofytes can be quite big, they hardly ever cause swallowing problems.

Esophagus pathology

As mentioned earlier problems in the esophagus can give the sensation of a problem in the throat.

In the video there is stasis of contrast in the proximal esophagus due to a large carcinoma.

A common cause of swallowing problems is reflux which irritates the cricipharyngeal muscle and results in hypertrophy.

The patient in the video has a large hiatal hernia with reflux and almost no peristatic movements in the esophagus.

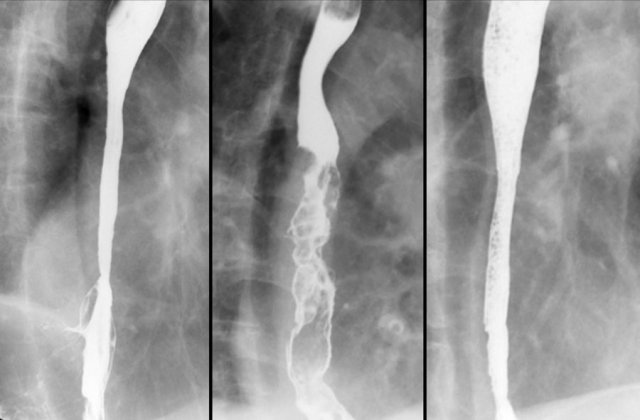

Here three patients with swallowing problems as a result of esophageal pathology.

The patient on the left has reflux esophagitis with a Barrett's esophagus.

The patient in the middle has a esophageal cancer.

The patient on the right has a stricture due to ingestion of caustic material.

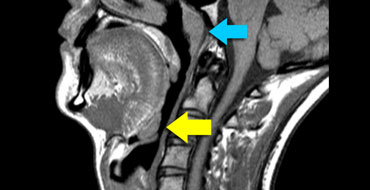

Lingual tonsils

The lingual tonsils are nodules of lymphatic tissue at the back of the base of the tongue (yellow arrow).

They are similar to the adenoid or nasopharyngeal tonsil (blue arrow).

Large lingual tonsils can be a cause of dysphagia or globus sensation especially if the tonsils compress the epiglottis.

In many cases however they are incidental findings.

Endoscopy is sometimes needed to differentiate large tonsils from a carcinoma at the tongue base.

Notice that you have to look carefully to detect the large lingual tonsil.

Diagnosis

The results of the swallowing examination help in establishing a final diagnosis.

Based on this examination alone however, a specific diagnosis usually cannot be made, since most severe swallowing disorders are the result of a complex neuromuscular dysfunction.

Hence the swallowing study should be regarded as part of the total evaluation of the patient by gastroenterologist, neurologist and speech therapist.

The strength of the fluoroscopic examination is, that it is the only examination that can show us, what is really going on during swallowing and can therefore lead to a rehabilitation plan.

Swallowing Rehabilitation

Swallowing rehabilitation is a specialty on its own.

Here we will make some brief comments on rehabilitation as it may help you to better understand the dynamics of swallowing.

In unilateral pharyngeal paralysis stasis can be prevented by closing down one of the lateral food channels by turning the head towards the affected side or by manually compressing it.

Patients with aspiration before swallowing due to insufficient closure of the mouth, can be helped by flexing their head during chewing and thus holding the food in the anterior part of the oral cavity.

In patients with aspiration during or after swallowing the 'supraglottic swallow' may help.

Before swallowing a deep breath is taken.

Air is prevented to leak out of the airways by compressing the vocal cords.

Immediately after swallowing the patient has to cough forcefully in order to clear the airways and the throat from any residual food.

Some patients only aspirate when they ingest fluids.

These patients can be helped by changing their fluid intake into jelly-like liquids.