Acute Abdomen in Neonates

Joosje Bomer, Samuel Stafrace, Robin Smithuis and Herma Holscher

Akershus Universitetssykehus in Lørenskog, Norway, Sidra Medicine in Doha, Qatar, Alrijne hospital in Leiden and Juliana Children's Hospital in the Hague, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

A neonate with an acute abdomen usually presents with vomiting, constipation and distention of the belly.

When the symptoms are present immediately after birth, the most common cause is a gastrointestinal obstruction.

In this article we will discuss the congenital gastrointestinal obstructions and also some acquired diseases that present as an acute abdomen in the neonate.

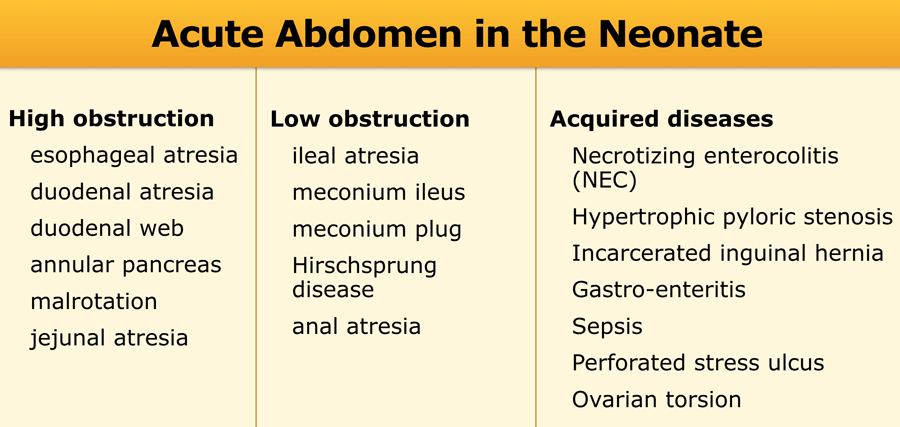

Differential diagnosis

The table on the left lists the differential diagnosis for acute abdomen in the neonate.

High obstructions are defined as proximal to the ileum.

Low obstructions are defined as occuring in the ileum or colon.

Although in high obstruction vomiting will be the most striking symptom, whereas in low obstruction this will be constipation, both symptoms are often present concurrently, and the clinical differentiation between a high and a low obstruction is difficult.

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) and hypertrophic pyloric stenosis are the most common acquired causes of an acute abdomen in the neonate.

NEC is most common in prematures, especially when there is an extreme low birthweight.

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis typically presents at the age of 4-8 weeks, but can sometimes present in the early neonatal period.

Imaging

Abdominal radiograph

In suspected neonatal obstruction the first step is an abdominal radiograph.

On the radiograph an obstruction can only be diagnosed if the bowel has had sufficient time to become air-filled after birth.

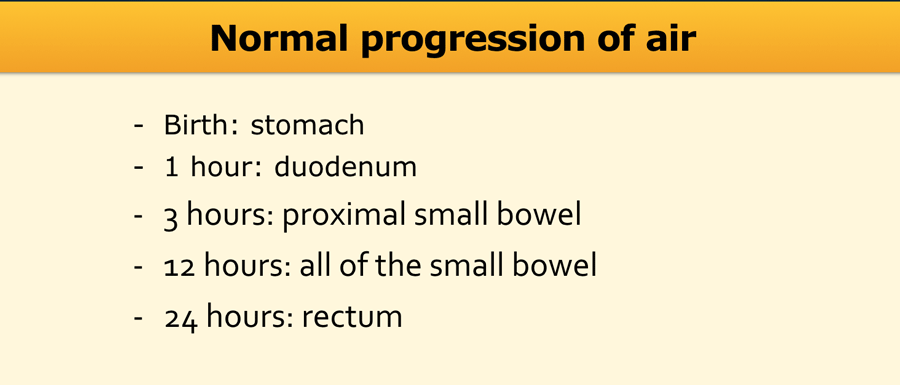

The table shows the normal progression of air in the gastrointestinal tract.

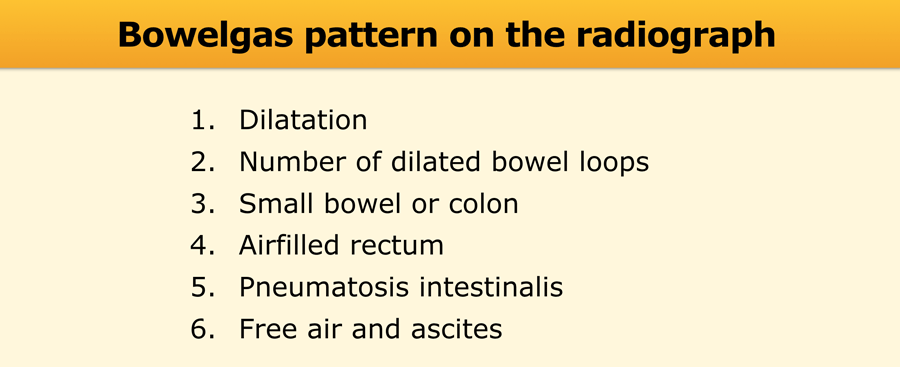

The things to look for on the abdominal radiograph are listed in the table.

We will discuss each of these items separately.

In addition to the front view, the dorsal decubitus radiograph (cross-table view with horizontal beams) should be performed, which can depict free air and sometimes can aid in differentiating the small intestine from the colon.

On the radiograph also check lines and catheters and study the lungs, soft tissues and skeletal structures.

Calcifications in the abdominal wall can be seen in meconium peritonitis.

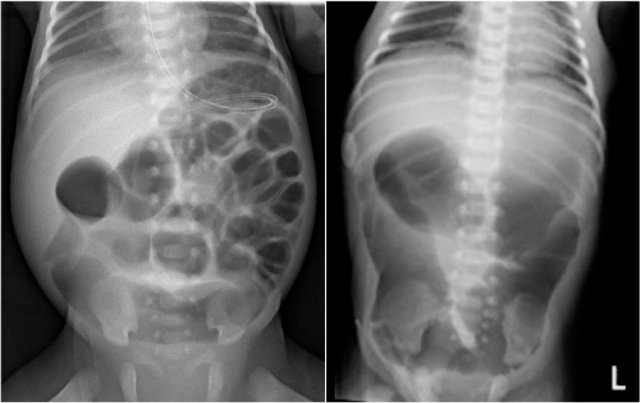

1. Dilatation?

When the bowel measures more than the interpedicular width of L2, it is said to be dilated.

Massive dilatation is seen in complete obstruction and is accompanied by fluid levels on the dorsal decubitus radiograph.

However, fluid levels alone do not necessarily correspond to dilatation, but rather reflect abnormal peristalsis.

An unchanging bowel gas pattern over time indicates absence of perstalsis.

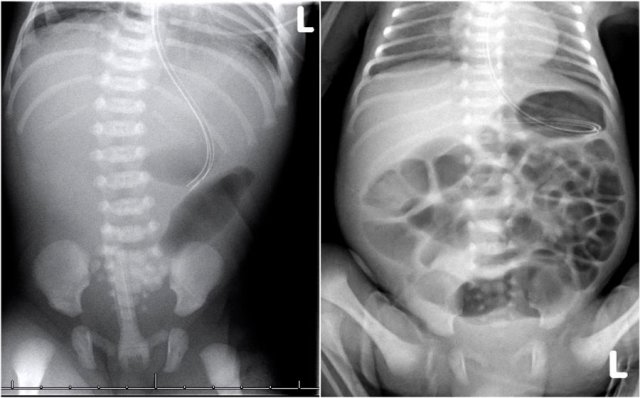

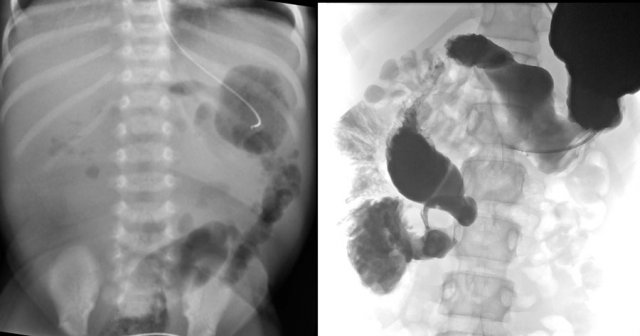

On the left image the bowel is dilated and the diameter exceeds L2 interpedicular width in a patient with meconium ileus.

On the image on the right there is massive dilatation in a neonate with jejunal atresia.

2. Number of dilated loops?

Up til three dilated small bowel loops on an abdominal radiograph generally indicate a high obstruction.

The left image shows a case of jejunal atresia.

More than three dilated loops indicate a low obstruction.

The image on the right is a case of ileal atresia.

3. Small bowel or colon?

Since neonates do not have haustra in the colon yet, it is often impossible to discriminate between small bowel and colon on an AP radiograph.

A dorsal decubitus radiograph may help as colonic obstruction may produce long fluid levels.

Furthermore, the colon ascendens, descendens and rectum are more dorsally located structures.

To discriminate small bowel from large bowel with certainty is only possible with a colon enema.

4. Airfilled rectum?

If sufficient time has gone by after birth, the rectum will be filled with air.

Absence of rectal air indicates an obstruction.

In Hirschsprung's disease there is usually no air in the rectum or only a thin stripe of air.

The image shows a neonate with dilated bowel loops.

There is no air in the rectum.

This patient had a meconium ileus.

5. Pneumatosis intestinalis?

Study the image.

What are the findings?

Then scroll to the next image.

Findings:

- What at first sight looks like granular feces in the bowel (yellow arrow) is actually caused by gas in the bowel wall seen en face.

- Air in the bowel wall is most easily recognized when seen in profile as linear black lines that parallels the bowel lumen (green arrows).

Pneumatosis intestinalis is defined as gas in the bowel wall.

In neonates it is seen in bowel wall ischemia in necrotizing enterocolitis.

On the radiograph pneumatosis intestinalis resembles granular feces, which is a normal finding in older children.

Neonates however do not have granular feces yet since they only drink milk.

So what looks like granular feces in the bowel actually represents intramural gas.

The air bubbles can be resorbed into the venous system causing portal venous gas.

Pneumatosis intestinalis can lead to perforation seen as pneumoperitoneum.

6. Free air and ascites?

Large amounts of free air can be seen on the front radiograph under the diaphragms, when visualizing both sides of the bowel wall and outlining the falciform ligament.

Small amounts of free air can only be detected on the dorsal decubitus radiograph.

Ascites can only be suspected on a radiograph when the amounts are large enough to cause the bowel to float and cluster in the center of the abdomen.

The presence of both ascites, free air as well as abdominal wall calcifications indicate that there has been a perforation in utero with meconium peritonitis.

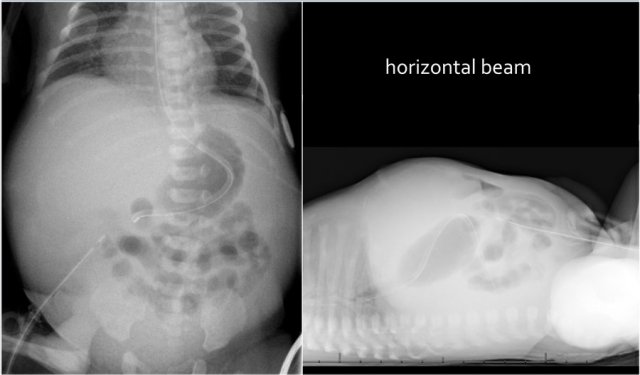

Upper GI study

In case of a typical complete high obstruction (see below) on the radiograph no further imaging is needed and upper GI series are not advised as they may only cause aspiration.

When the obstruction is incomplete or imaging results are equivocal, an upper GI is indicated.

First aspirate air from a distended air-filled stomach.

Always use water-soluble contrast in neonates and inject slowly.

Do not distend the stomach too much.

Look for dilatation and stenosis and document the position of Treitz' ligament.

To correctly depict Treitz' ligament, the child has to lie flat and straight as rotation may falsely simulate malrotation.

If you do not plan to take more images later, aspirate the injected contrast from the stomach at the end of the examination.

Here an upper GI study showing the normal position of Treitz' ligament to the left of the spine (arrow).

It reaches as high as the bulbus duodeni or even higher.

In malrotation, which we will discuss later, Treitz is positioned to the right of the spine.

Microcolon: elongated colon with smalldiameter. It indicates that meconium has not reached the colon yet. Once the obstruction is relieved and bowel contents pass through the colon, the colon will develop normally without remaining consequences.

Microcolon: elongated colon with smalldiameter. It indicates that meconium has not reached the colon yet. Once the obstruction is relieved and bowel contents pass through the colon, the colon will develop normally without remaining consequences.

Colon enema

In cases of suspected low obstruction, a colon enema is indicated.

Use water-soluble contrast for two reasons: the thick barium can make the evacuation of meconium even more troublesome and water-soluble contrast can be an effective therapeutic enema in cases of meconium plugging or meconium ileus.

You may choose to use a balloon catheter, but do not distend the balloon prior to evaluating the rectum and excluding Hirschsprung disease, as the high pressure from the balloon can cause a rectal perforation!

In experienced hands a balloon can be inflated if this is deemed necessary to reach complete filling and do this under careful fluoroscopic vision.

Lateral images from the rectum and sigmoid should be documented first followed by frontal images.

Focus on the diameter of the rectum versus the remainder of the colon, the presence of a microcolon and meconium pellets.

In Hirschsprung disease it is sufficient to determine the length of the affected bowel, but in other conditions one should aim for filling of the terminal ileum, as the obstruction can be located in the ileum.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound plays a limited role in depicting GI tract pathology as the gas-filled bowel will strongly reflect the ultrasound beam.

There are however some exceptions.

- In case of a volvulus, the bowel is not necessarily dilated and ultrasound can show the twisting of the mesenterial vessels.

- Pneumatosis intestinalis in NEC can be seen as small echogenic dots within the bowel wall.

- Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, which we will discuss later is a typical ultrasound diagnosis.

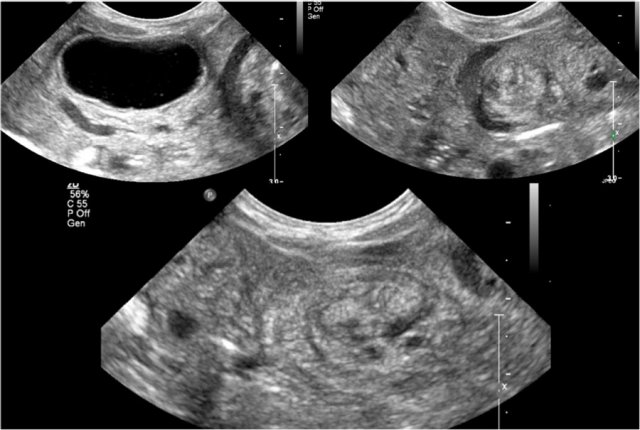

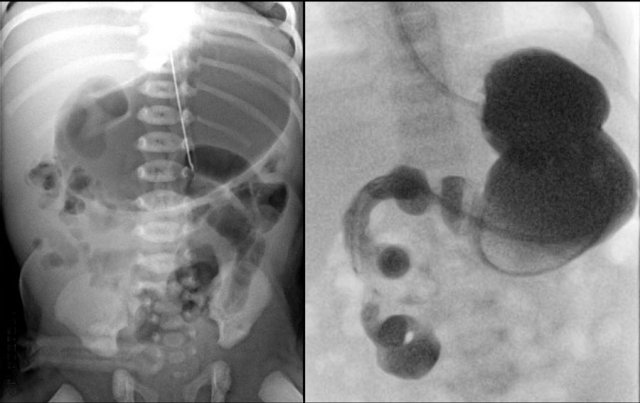

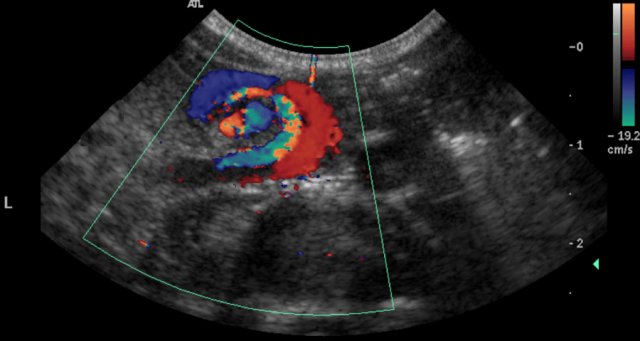

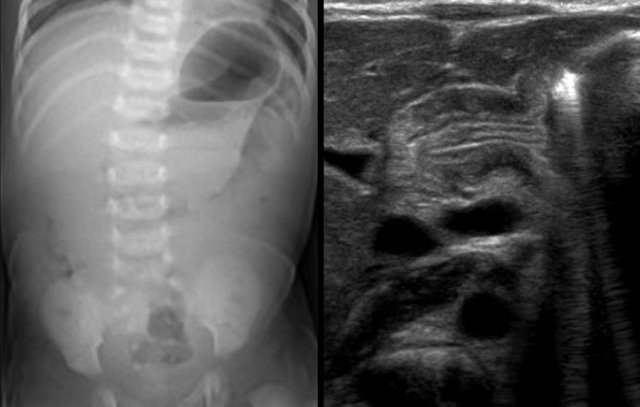

Here ultrasound images of a neonate who presented with an acute abdomen.

An ultrasound antenatally had detected a duplication cyst.

On the ultrasound there is a whirlpool sign of the vessels.

Torsion of the cyst and the mesentery had resulted in a volvulus.

This is a medical emergency and consequently the neonate went straight to the operating room.

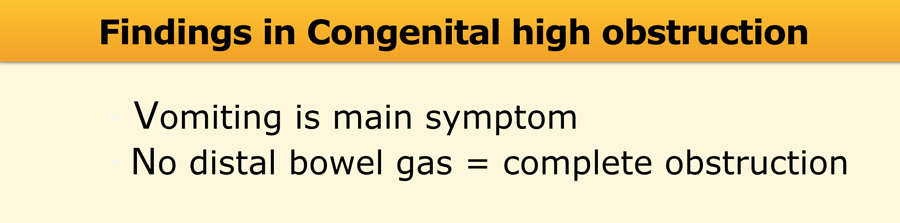

Congenital High Obstruction

Most high obstructions occur at the level of the duodenum.

Vomiting will be non-bilious if the obstruction is localized proximal to the Vater ampulla, and bilious (the color or which is green) if it is localized distal to it.

Bilious vomiting is an indication for urgent imaging as a volvolus may be present.

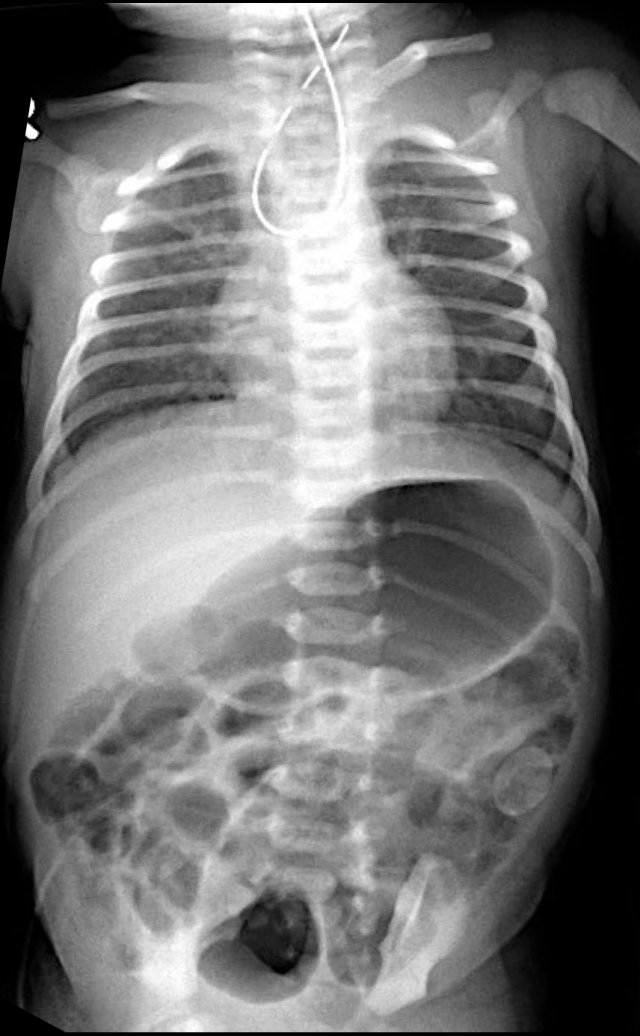

Esophageal atresia

First look at the image and describe the findings.

Then continue reading.

The findings are:

- Feeding tube cannot be passed and lies in a dilated proximal esophagus

- Normal air in the abdomen.

Diagnosis: esophagus atresia with a distal tracheo-esophageal fistula

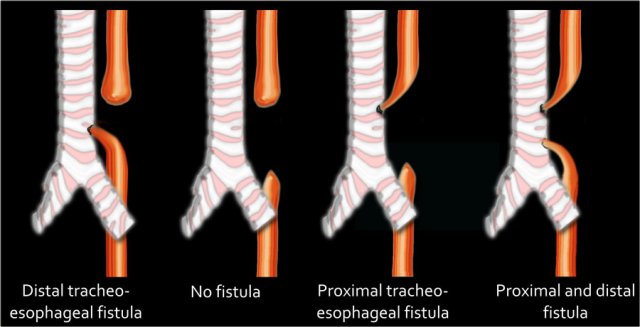

Esophagus atresia is an anomaly which arises in the fourth week of the embryogenesis, at a stadium in which the trachea and esophagus should separate from each other.

In case of failure of complete separation esopaghus atresia can occur.

Clinically the neonate cannot swallow saliva, may blow bubbles and will aspirate on feeding.

When a feeding tube is inserted it cannot be passed distally.

A radiograph with a curled up feeding tube will confirm the diagnosis.

Contrast swallow studies should not be performed as they can cause severe aspiration.

Often the proximal pharyngeal pouch is dilated.

In 80% of cases a distal tracheo-esophageal fistula is present.

Less common is:

- no fistula - no air in stomach

- proximal fistula - no air in stomach

- two fistulas - air in stomach

First look at the image and describe the findings.

Then continue reading.

The findings are:

- Feeding tube cannot be passed and lies in the proximal esophagus

- Gasless abdomen

- This indicates that there is no distal tracheo-esophageal fistula

Cases without a distal fistula can be suspected antenatally when there is a polyhydramnion and an empty stomach.

Always screen the radiograph for other anomalies as esophagus atresia can be part of the VACTERL association (vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, cardiovascular malformations, tracheo-oesophageal fistula, renal and limb anomalies).

Duodenal atresia

In duodenal atresia the duodenum fails to canalize properly late in the first trimester and a web or several webs occur.

In cases of atresia the web is complete.

Most often the atresia occurs distal to Vater's ampulla.

The obstruction causes the duodenum to expand and this creates the double bubble sign (dilated stomach and duodenum).

When a polyhydramnion and a double bubble are present antenatally, the diagnosis can be suspected before birth.

First look at the image and describe the findings.

Then continue reading.

The findings are:

- Double bubble without distal bowel gas.

This confirms the diagnosis of duodenal atresia and no further imaging is needed.

In extreme prematures the diagnosis can be more challenging when the duodenum has not had enough time to dilate.

Here another case of duodenal atresia with the typical double bubble sign.

Note that the nasogastral tube may decompress the stomach and duodenum limiting the interpretation of the film.

One may inject some air through the tube prior to the film.

About 30% of the patients with duodenal atresia have Down syndrome and there is an association with VACTERL malformations, malrotation and biliary tree abnormalities.

Duodenal web

First look at the image and describe the findings.

Then continue reading.

The findings are:

- Dilated stomach

- To a lesser extent dilated proximal duodendum

- Distal bowel gas is present indicating an incomplete duodenal obstruction.

This radiograph was taken only a few hours after birth and air has not reached the distal small bowel and colon yet.

Duodenal web has the same etiology as duodenal atresia, but the web is fenestrated and the obstruction is incomplete.

Depending on the severity of the stenosis, patients may present in the neonatal period or at a later age.

Radiographs may show a double bubble, but with distal bowel gas being present.

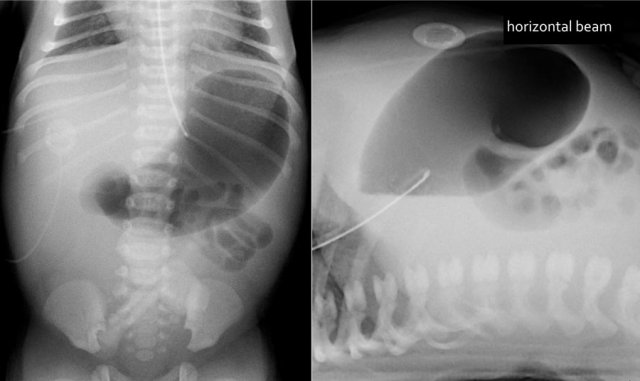

Here another case of a duodenal web.

Both radiographs and upper GI series cannot differentiate between duodenal web and annular pancreas.

Annular pancreas however, is less common.

It is often discovered incidentally or in adults when the associated abnormal biliary drainage causes pancreatitis.

Another rare diagnosis with similar radiological findings is the preduodenal portal vein - often associated with other abnormalities in the abdomen (like situs ambiguus).

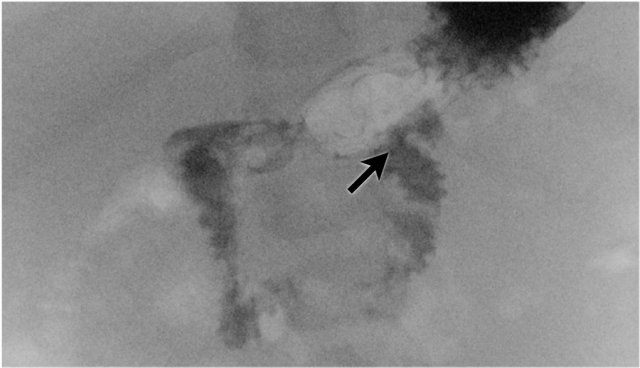

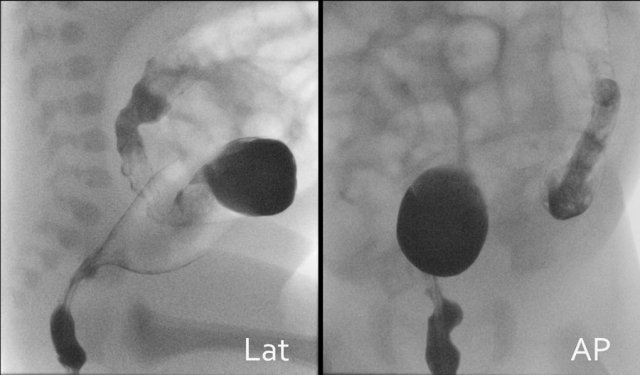

First look at the images of the upper GI-study and describe the findings.

Then continue reading.

The findings are:

- Dilated proximal duodenum (asterix)

- Small amount of contrast passes through the duodenal web to the distal duodenum (arrow)

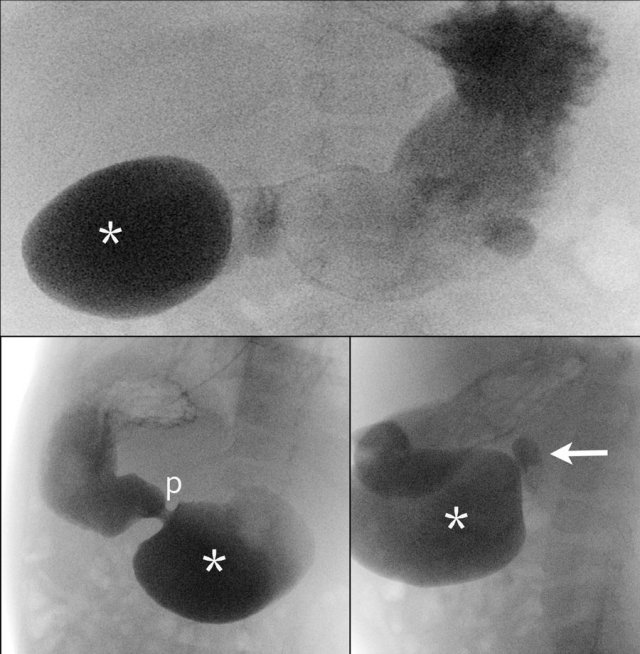

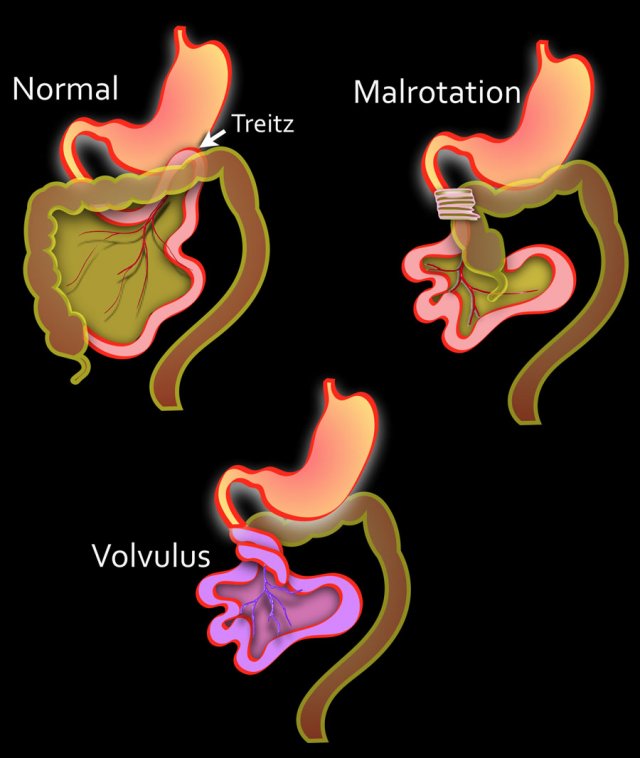

Malrotation

In the developing embryo growth of the bowel requires herniation into the omphalomesenteric sac.

In the tenth week of gestation the bowel returns to the abdominal cavity.

This return is accompanied by a counterclockwise rotation of the midgut to achieve its final position with the ligament of Treitz in the left upper quadrant and the caecum in the right lower quadrant, suspended from a long mesentery.

Malrotation arises when the rotation is arrested or even reversed.

As a result the bowel has an abnormal position, the mesentery is short and peritoneal bands, called Ladd's bands, may cross from the caecum to the liver or to the anterior abdominal wall.

- Left

Normal situation with the duodenum retroperitoneal.

Treitz ligament is on the left side of the spine.

The small intestine is predominantly on the left.

The cecum is in the right lower quadrant

There is a long mesentery.

- Middle

Displacement of Treitz inferiorly and rightward.

The small intestine is found predominantly on the right.

Fibrous bands course over the vertical portion of the duodenum causing obstruction. - Right

Volvulus due to short mesentery. Ischemic bowel.

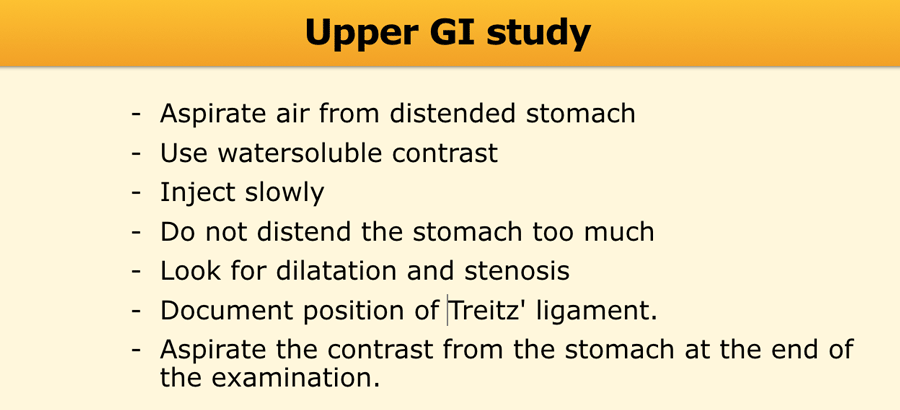

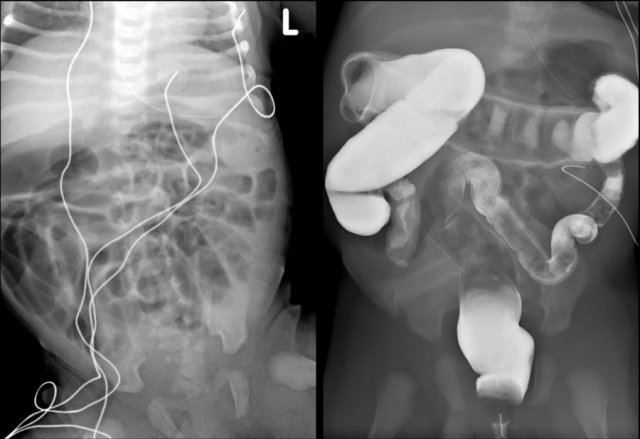

Here a neonate with a malrotation.

The abdominal radiograph is non-specific (image on the left)

The upper GI study clearly demonstrates that the small bowel projects to the right of the spine.

The malrotation will become symptomatic only when a volvulus occurs due to the short mesentery or when the Ladd's band obstruct the duodenum

Both presentations are most common in the neonatal period.

However sometimes it can also present later in life, for example when the volvulus is intermittent or when the Ladd's bands create relatively little obstruction.

Acute volvolus is a life-threatening presentation and requires prompt surgical intervention.

The upper GI-study shows a malrotation complicated by a volvulus.

This results in the typical corkscrew or reversed 3 sign.

An overfilled stomach could hide the corkscrew on the AP projection so the stomach should first be aspirated by use of a nasogastric tube and the volume of injected contrast should be small.

Sometimes a malrotation can be suspected when on ultrasound the superior mesenteric artery is seen to lie to the right of the superior mesenteric vein.

This sign however is neither specific nor sensitive and should not be used when asked to investigate for suspected malrotation without a volvulus.

An abnormal location of ligament of Treitz on an upper GI series is the gold standard for malrotation.

In case of a volvolus the child is acutely sick and ultrasound is often the modality of choice.

This will show a whirlpool sign of the vessels which confirms the presence of a volvolus.

The corkscrew sign of the bowel on the upper GI is equivalent.

Once a volvolus is diagnosed on ultrasound, the child should go straight to the operating room and no more time should be lost on further imaging.

Jejunal atresia

Jejunal atresia is the most frequent cause of upper intestinal obstruction.

It is caused by an ischemic event in utero.

Antenatally a polyhydramnion will be present.

More atretic foci can be present simultaneously.

A typical case will show a triple bubble sign on a radiograph, with the third bubble being the dilated jejunum (figure).

The radiographs however are not always straightforward.

When in doubt, an upper GI-study is indicated which will confirm the occlusion.

Here another case of jejunal atresia.

Congenital Low Obstruction

A low obstruction is an obstruction in the ileum or in the colon.

Passage of meconium should normally occur within 48 hours from birth.

In a low obstruction the neonate will have difficulty passing meconium or will not pass any meconium at all.

Because of the constipation the child will start to vomit.

The presence of a microcolon on the colon enema indicates that the meconium has not reached the colon and the obstruction is situated proximal to the colon.

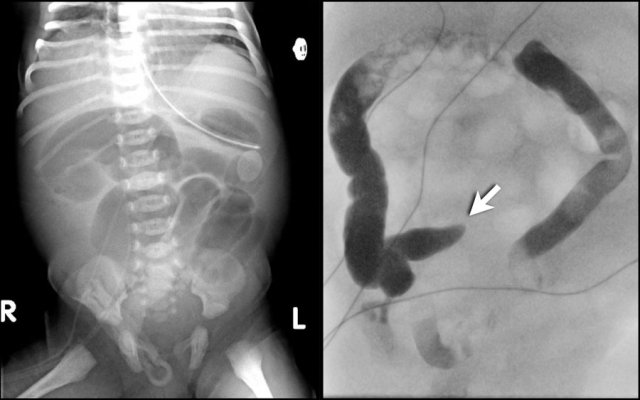

Ileal atresia

As with jejunal atresia, ileal atresia results from an in utero ischemic event.

More atretic foci can be present simultaneously, but the distal ileum is the most common site to be involved.

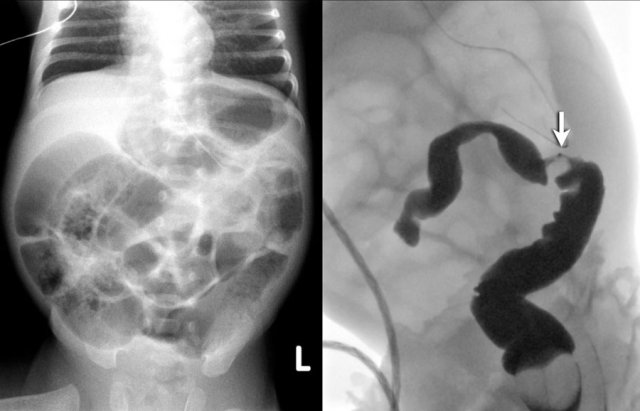

Radiographs will show multiple dilated bowel loops and absence of air in the colon as seen on the image on the left.

A colon enema will show a microcolon with contrast filling ending blind in the ileum (arrow on image on the right).

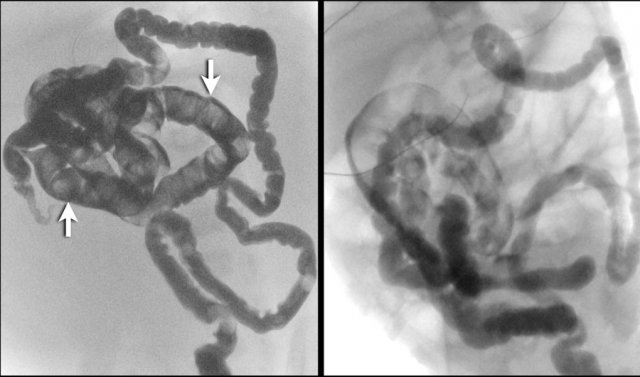

Meconium ileus

Meconium ileus occurs nearly exclusively in patients with cystic fibrosis.

In 10% of patients it is the first presentation of the disease.

Due to the exocrine dysfunction of the pancreas and abnormal intestinal secretions, the meconium is abnormally thick and becomes impacted in the ileum.

It is the neonatal equivalent of DIOS (distal intestinal obstruction syndrome).

Sometimes radiographs demonstrate typical 'soap bubbles', which represent captured air between meconium pellets.

The tenacious meconium prevents the occurence of air fluid levels on the decubitus image.

Bowel loops are usually of different caliber and not all loops are dilated. Colon enema shows a microcolon with stacked meconium pellets in the ileum.

Once you have made the diagnosis of a meconium ileus, you can opt to set in moderately hyperosmolar contrast for therapeutic purposes as this can help to dissolve the meconium and act as an effective enema.

Since the hyperosmolar contrast will create a fluid shift and thereby may cause dehydration, it is of importance to clearly communicate with the clinician to administer extra fluids and secure continuous careful surveillance.

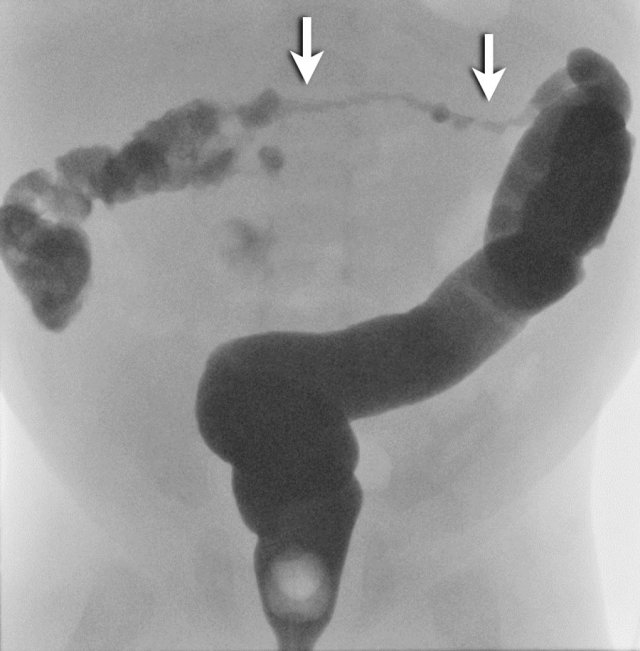

Here two cases of meconium ileus.

There is a microcolon and there are multiple meconium pellets in the distal small bowel (arrows).

Meconiumplugsyndrome: normal rectum and a small diameter to the left colon. Because the child has a functionally normal rectum he continued to evacuate the contrast and a balloon catheter had to be used.

Meconiumplugsyndrome: normal rectum and a small diameter to the left colon. Because the child has a functionally normal rectum he continued to evacuate the contrast and a balloon catheter had to be used.

Meconium plug syndrome

Meconium plug syndrome is also known as small left colon syndrome.

Meconium plugging in the left colon occurs when the colon is functionally immature with little motility.

There is an association with maternal diabetes and drug use in pregnancy. The condition is temporarily and when the meconium plugs resolve, the colon distends normally and functions normally.

The neonate is otherwise healthy and there is no association with cystic fibrosis.

There is no air in the rectum on the radiograph.

Colon enema shows a normal rectal diameter which excludes Hirschsprung disease.

A microcolon is absent.

Meconium is found throughout the colon, but most typically found in the left colon, which may also have a smaller diameter.

Just as with a meconium ileus, you may now opt to give a hyperosmolar contrast enema to help resolve the meconium (see above).

Hirschsprung disease

In Hirschsprung disease ganglion cells are absent in the distal part of the colon.

Because the intestinal ganglion cells migrate in a craniocaudal direction, the area of aganglionosis always involves the rectum.

More extensive disease extends orally in a contiguous fashion.

The involved bowel has a small diameter and the bowel proximal to the affected segment is dilated.

In Hirschsprung disease the ratio between the denervated and the non-affected bowel is <1.

It is important to describe the length of the affected segment.

Most cases are short-segment and total aganglionosis is rare.

In case of total aganglionosis the diagnosis is difficult, because the entire colon has a small caliber and resembles a microcolon.

Start the enema in the lateral position to evaluate the rectum.

Save cine images from the first contrast injection, as with progressive filling signs can become obscured by too much bowel distention.

Normally the rectum should be wider than the sigmoid.

The image shows an abnormal recto-sigmoid index <1.

Here another case of Hirschsprung disease.

The definitive diagnosis of Hirschsprung disease is confirmed with biopsy.

About 90% of Hirschsprung disease is diagnosed in the neonatal age, but some cases are discovered later in life.

Anal atresia

The diagnosis of anal atresia is usually clinically straightforward by inspection and digital palpation.

Anal atresia is part of the spectrum of anorectal and cloacal malformations and is a complex disorder.

Imaging and treatment should be performed in specialized centers.

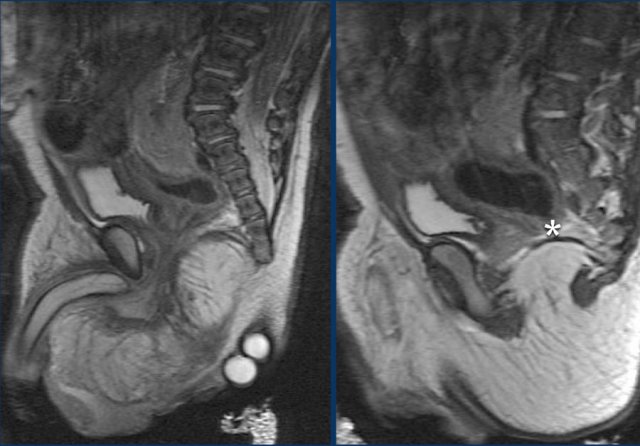

Initially plain films and ultrasound can be used to show the position of the malformation and the need for a colostomy.

At a later stage and prior to definitive surgery a combination of fluoroscopic studies and MRI will be used to show the complex anatomy of anorectal, genitourinary, pelvic and perineal structures and associated fistulas.

Anal atresia is part of the VACTERL malformations and patients should be screened for concomittant anomalies.

Acquired causes of acute abdomen

Necrotizing enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis is a severe bowel inflammation.

The etiology is not entirely clear and seems to be a combination of immature bowel mucosa, infection and ischemia.

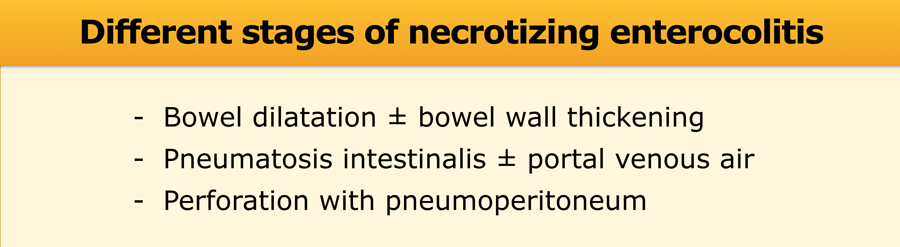

Initially radiographs are nonspecific and may only show bowel dilatation.

Absence of a changing bowel pattern over time is worrisome.

Pneumatosis intestinalis and portal venous air (pneumoportogram) can both be seen on radiographs and with ultrasound.

The most feared complication is perforation.

NEC occurs most often, but not exclusively, in prematures.

Neonates with severe stress, for example with cardiac disease, are also at risk.

Clinically, retentions and bloody stools can be a key to the diagnosis.

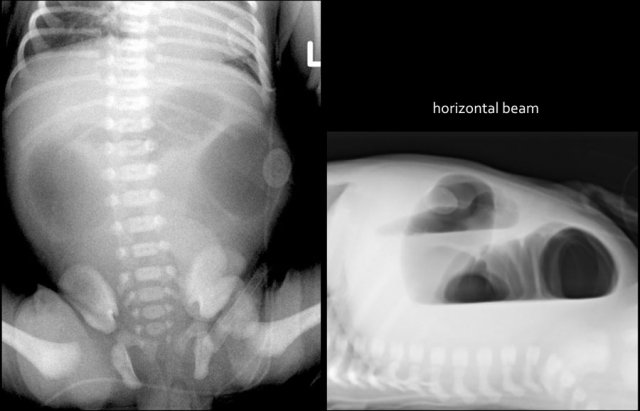

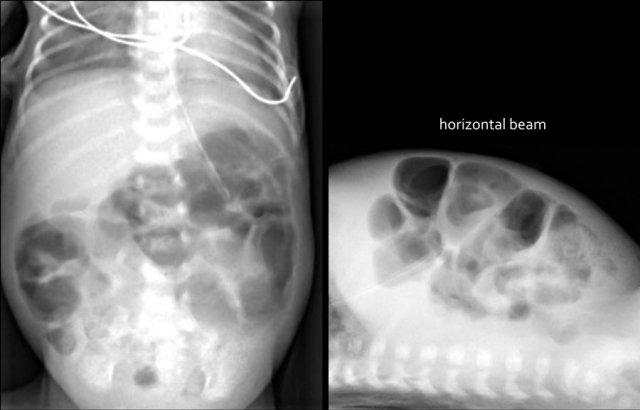

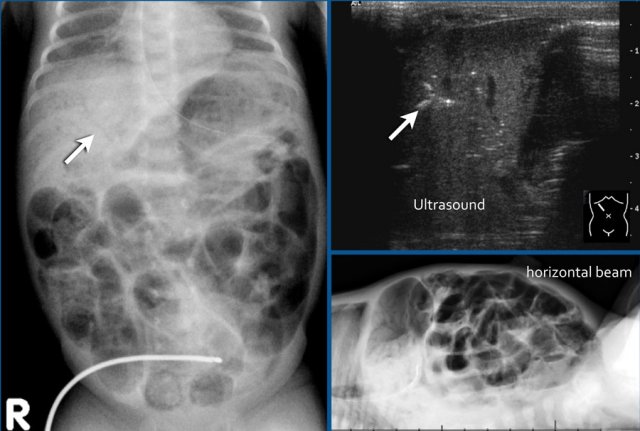

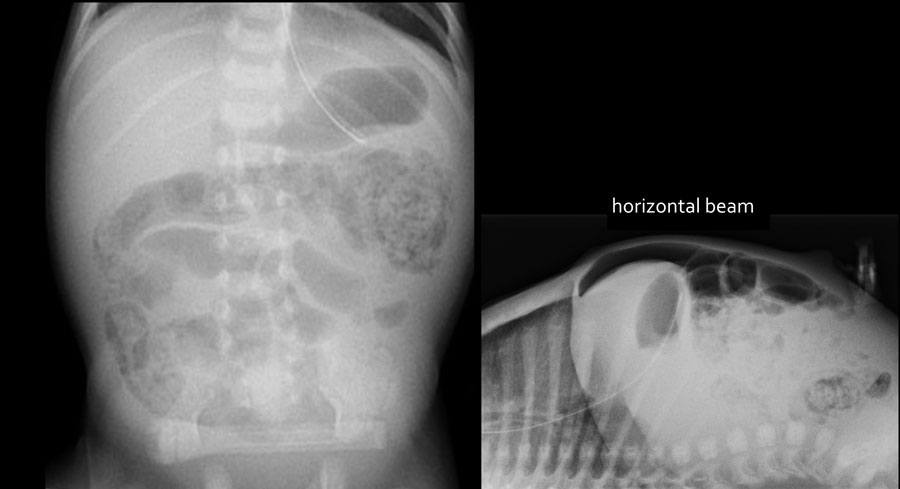

The images show a typical case of NEC with pneumatosis intestinalis.

On the horizontal beam image there is no sign of free air.

Here images of a neonate who developed NEC.

At this early stage the radiograph only shows non-specific bowel dilatation.

At this stage you cannot make the diagnosis.

Here another typical case of NEC.

Notice the air in the portal vein (arrow) and peripheral portal branches.

This is seen on the X-Ray and on ultrasound.

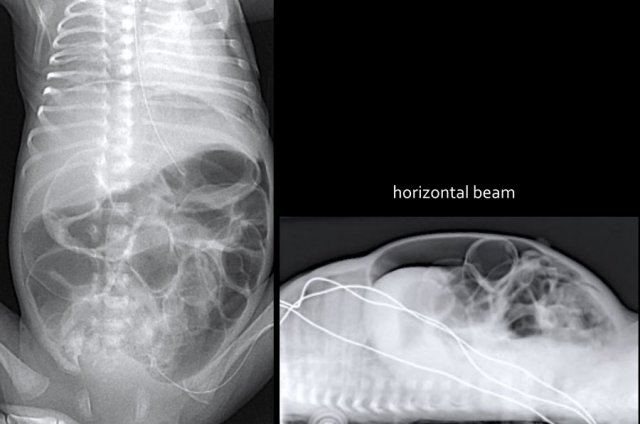

In this patient with NEC notice all the airbubbles in the wall of the bowel and within the liver.

Pneumoperitoneum in severe NEC.

Air can be seen on both sides of the bowel wall.

This is called the Rigler sign.

In about 20% of patients with NEC strictures can occur in a later stage.

Sometimes necrotizing enterocolitis can have a subclinical course and strictures are the only sign the newborn has endured the disease.

The image on the left is taken 6 days after birth and shows distended bowel with pneumatosis intestinalis.

A colon enema at 6 weeks of age shows a stricture in the colon descendens (arrow).

Here a long stricture in the colon transversum in a child who had a NEC.

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis

Projectile vomiting is the key feature in patients with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis.

The cause of the muscle hypertrophy which causes the gastric outlet obstruction is unknown.

There is a familial predisposition and it is more common in boys.

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis typically presents after the neonatal period, at the age of 4-8 weeks.

However early presentation can also occur.

Ultrasound in a fasting child will show retained fluid in the stomach. There is no passage along the hypertrophic pyloric muscle.

For optimal viewing the child must be positioned right side down and if the stomach is empty it should be filled by drinking Pedialyte or glucose solution during the examination.

If the stomach is too full, the child can be placed on the left side to help the pylorus to move anteriorly.

The transversal diameter of the single muscle wall is the most reliable measurement to diagnose pyloric muscle hypertrophy.

A measurement of more than 3 mm on a transverse image indicates hypertrophy.

A transverse total diameter more than 14 mm and a total length of the pyloric canal more than 15 mm support the diagnosis.

- Single muscle wall > 3mm

- Total transverse diameter > 14mm

- Length pyloric canal > 15mm

Incarcerated hernia

Neonates and especially prematures have a relatively weak abdominal wall and inguinal hernias are common, especially in boys.

In case of multiple dilated bowel loops on the radiograph, always check the groins for the presence of a hernia containing a bowel loop (figure).

Ultrasound is the modality of choice to evaluate hernias, and in girls it is important to look for herniation of the ovaries.

Study the image.

What are the findings and what is your diagnosis.

The findings are:

- Multiple dilated bowel loops indicating a distal obstruction.

- Bowel loop in the left groin

This was an incarcerated inguinal hernia.

Quiz cases

Case 1

Study the image.

What are the findings and what is your diagnosis.

Then scroll through the images for the diagnosis.

The findings are:

- The abdominal radiograph shows the triple bubble sign without distal bowel gas.

- Abdominal calcifications

Diagnosis:

Jejunal atresia and in utero perforation with meconium peritonitis.

Case 2

Study the image.

What are the findings and what is your diagnosis.

Then scroll through the images for the diagnosis.

The findings are:

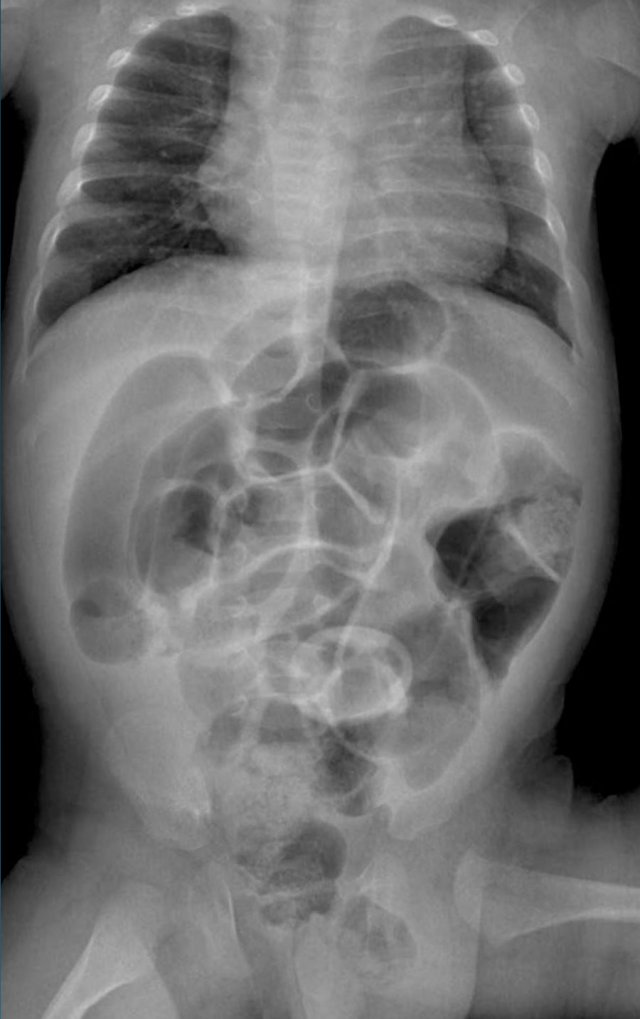

- Multiple dilated small bowel loops indicate a low obstruction

- Contrast enema show a small caliber of the rectum compared to the caliber of the sigmoid

- The rectum shows saw tooth contractions.

Diagnosis:

Short segment Hirschsprung disease.

Case 3

Study the image.

What are the findings and what is your diagnosis.

Then scroll through the images for the diagnosis.

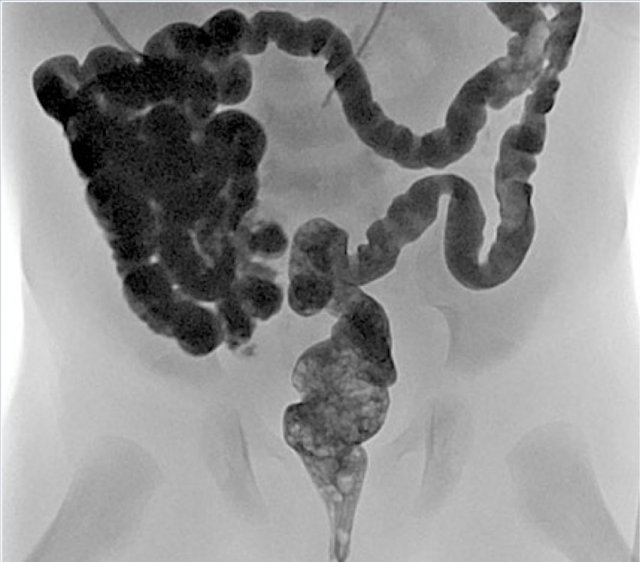

The findings are:

- Multiple dilated small bowel loops indicate a low obstruction

- Contrast enema show a small caliber in the rectum, sigmoid and colon descendens

Diagnosis:

Long segment Hirschsprung disease

Case 4

Study the image.

What are the findings and what is your diagnosis.

Then scroll through the images for the diagnosis.

The findings are:

- Multiple dilated small bowel loops

- Pneumatosis intestinalis.

- Pneumoperitoneum.

Diagnosis:

NEC with perforation.